I;' August. 1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

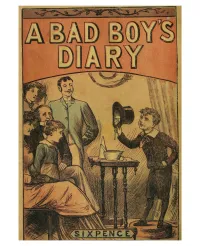

A Bad Boy's Diary

mmY Frederick Warne and Co., Publisliers, NOTABLE NOVELS. COMFX.ETS EDITIONS. Large crown 8vo, SIXPENCE each, Picture Wrappers. 1 SCOTTISH CHIEFS. Miss JANB POET'EII. 2 UNCLB TOM'S CABIN". HABBIZT BjiECHIiB STOWE. 3 ST. CLAIK OF THE ISLES. ELIZABETH HELME. 4 CHILDEEW OF THE ABBEY. E. M. EocHE. 5 THE LAMPIiIGHTEE. Miss CUMMINS, 6 MABEL VAXJGHABT. Miss CUMMINS. 7 THADDEUS OF "WARSA-W. Miss PuRTER. 8 THE HOWARDS OF GLEN LUWA. Miss WARNER. 9 THE OLD ENGLISH BABON, &o. &<i. CLARA EEETE. 10 THE HUNGARIAN" BROTHERS. Miss POBTEE. 11 MARRIAGE. Miss FEKEIEE. 12 INHERITANCE. Miss FEBBIEE. 13 DESTINY. Miss FEBEIEB. 14 THE KING'S O-WN. Captain MAEETAT. 15 THE NAVAL OFFICER. Cai'tain MAEETAT. 16 NE-WTON FORSTER. Captain MABBTAT. 17 RICHELIEU. G, P, R. JAMES. 18 DARNLEY. G. P, E, JAMES. 19 PHILIP AUGUSTUS. G, P, E, JAMES. 20 TOM CRINGLE'S LOG. MICHAEL SOOTT. 21 PETER SIMPLE. Captain MARRTAT. 22 MARY OF BURGUNDY. G, P. E. JAMES. 23 JACOB FAITHFUL. Captain MAEETAT. 24 THE GIPSY. G. P, E, JAMES. 25 CRUISE OF THE MIDGE. MICHAEL SCOTT. 26 TWO YEARS BEFORE THE MAST. E. H. DANA. 27 THE PIRATE, AND THE THREE CUTTERS, Captain MAEETAT, 23 HENRY MASTERTON. G, P. E, JAMES. 29 JOHN MAESTON HALL. G, P, E. JAMES. 30 JAPHET IN SEARCH OF A FATHER. Captain MARBYAT. 31 THE •WOLF OF BADENOCH. Sir THOMAS DICK LAUDEK. 32 CALEB "WILLIAMS. WILLIAM Goowiif. 33 THE PACHA OF MANY TALES. Captain MAEETAT. 34 THE VICAR OF "WAKEFIEBD, OLITEE GoLDSMITn. 35 MR. MIDSHIPMAN EASY. Captain MARRTAT. 36 ATTILA. G. -

Volume I. Washington City, D. C., April 23, 1871. Number 7

<d VOLUME I. WASHINGTON CITY, D. C., APRIL 23, 1871. NUMBER 7. A HYMN TO THE TYPES. ing revolution of the earth, and hear the march bably; of my own age, though her self-pos- "In a month I set out for my trav&k. An- in the morning, there to nod in chairs by the the foot-lights shouting "fire! fire!" A terri- records, an order issued to the legation in Paris Mr. Babbitt observed that part of the leather W8S I BT CHAIUJEB'. O. KALPINE. of the moon in her attendant orbit. session might have stafliped her as much older; easy coach conveyed me to Londph, and the side of a bed-ridden mother, a widow whom ble uproar succeeded. The manager went when Mr. Polk was President, and Mr. Buchanan discolored ; and wheu he reached the boat, a t'h'éy supported oii their hard won pittance, Secretary of Stute, directing the minister to send darkly colored liquid was dripping from the sack. H O eiliinl. myriad army, whbse trae metal "My parents loved mfe tenderly, and, fail- but the bloom of her cheek, and her bosom just third day I lay sick in Paris. Sqr§ of Bftdy on tho stage and tried to quiet the alarmed such private letters as he might place in the dis- With lufinlte labor he Worked his dispatches • Ne'er flinched nor blenched before the despot Wrong! ing to soothe or conciliate me, they removed ripening, were indices of a girl's years. She and of brain, strained in nerve, and stunned fifty Cents, or at most a dollar a night. -

Rebecca Sugar Songs from Adventure Time & Steven

REBECCA SUGAR SONGS FROM ADVENTURE TIME & STEVEN UNIVERSE This book is a collection of ukulele tabs for songs by Rebecca Sugar from shows Adventure Time and Steven Universe. Tabs, lyrics, and background art by Rebecca Sugar. Rebecca Sugar is an American artist, composer, and director who is best known for being a writer and storyboard artist on Adventure Time as well as being the creator of Steven Universe. Material gathered and book designed by Angela Liu. Cover art and icons provided by Angela Liu. Made for Communication Design Fundamentals, 2015 (Carnemgie Mellon University). Table of Contents Adventure Time 4 - As a Tropical Island 6 - Oh Fionna 8 - My Best Friends in the World 10 - Remember You 12 - Good Little Girl Steven Universe 14 - Steven Universe Theme 16 - Be Wherever You Are As a Tropical Island Adventure Time / Season 3, Ep 2: Morituri Te Salutamux Air date: July 18, 2011 G C D7 G On a tropical island, on a tropical island. G C D7 G On a tropical island, on a tropical island! G C On a tropical island, D7 G Underneath a motlen lava moon. G C Hangin’ with the hoola dancers, D7 G Asking questions cause they got all the answers. G G Puttin’ on lotion, sitting by the ocean. C D7 Rubbin’ it on my body, rubbin’ it on my body. G G B7 Cmaj7 Get me out of this ca-a-ave, C7 G B7 Cmaj7 cause’ it’s nothin’ but a gladiator gra-a-ave. G G B7 Cmaj7 And if we stick to the pla-a-an, C7 G B7 Cmaj7 I think I’ll turn into a lava ma-a-an. -

Rebecca Sugar Songs from Adventure Time & Steven

REBECCA SUGAR SONGS FROM ADVENTURE TIME & STEVEN UNIVERSE 1 Table of Contents Adventure Time 4 - As a Tropical Island 5 - Oh Fionna 6 - My Best Friends in the World 8 - Remember You 10 - All Gummed Up Inside 11 - Oh Bubblegum 12 - Good Little Girl Steven Universe 14 - Steven Universe Theme 15 - End Credits Song 16 - Drive My Van Into Your Heart 18 - Giant Woman 19 - Be Wherever You Are 20 - Strong in the Real Way This book is a collection of ukulele tabs for songs by Rebecca Sugar from shows Adventure Time and Steven Universe. Tabs, lyrics, and background art by Rebecca Sugar. Rebecca Sugar is an American artist, composer, and director who was a writer and storyboard artist on Adventure Time and is the creator of Steven Universe. Material gathered and book designed by Angela Liu. Cover art and icons provided by Angela Liu. Made for Communication Design Fundamentals, 2015. 2 3 As a Tropical Island Oh Fionna Adventure Time / Season 3, Ep 2: Morituri Te Salutamux Adventure Time / Season 3, Ep 9: Fionna and Cake Air date: July 18, 2011 Air date: September 5, 2011 G C D7 G C E7 Am On a tropical island, on a tropical island. I feel like nothing was real, until I met you. G C D7 G Dm G7 C G7 On a tropical island, on a tropical island! I feel like we connect, and I really get you. C E7 Am G C If I said “You’re a beautiful girl,” would it upset you? On a tropical island, Dm G7 D7 G Because the way you look tonight, Underneath a motlen lava moon. -

The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2021 The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival Gabriel Bugarin Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bugarin, Gabriel, "The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival" (2021). WWU Graduate School Collection. 1034. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/1034 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival By Gabriel Bugarin Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts ADVISORY COMMITTEE Dr. Kathryn Trueblood, Chair Dr. Jane Wong Dr. Chris Loar GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

Paper XVII. Unit 1 Nathaniel Hawthorne's the Scarlet Letter 1

Paper XVII. Unit 1 Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter 1. Introduction 1.1 Objectives 1.2 Biographical Sketch of Nathaniel Hawthorne 1.3 Major works of Hawthorne 1.4 Themes and outlines of Hawthorne’s novels 1.5 Styles and Techniques used by Hawthorne 2. Themes, Symbols and Structure of The Scarlet Letter 2.1 Detailed Storyline 2.2 Structure of The Scarlet Letter 2.3 Themes 2.3.1 Sin, Rejection and Redemption 2.3.2 Identity and Society. 2.3.3 The Nature of Evil. 2.4 Symbols 2.4.1 The letter A 2.4.2 The Meteor 2.4.3 Darkness and Light 3. Character List 3.1 Major characters 3.1.1 Hester Prynn 3.1.2 Roger Chillingworth 3.1.3 Arthur Dimmesdale 3.2 Minor Characters 3.2.1 Pearl 3.2.2 The unnamed Narrator 3.2.3 Mistress Hibbins 3.2.4 Governor Bellingham 4. Hawthorne’s contribution to American Literature 5. Questions 6. Further Readings of Hawthorne 1. Introduction 1.1 Objectives This Unit provides a biographical sketch of Nathaniel Hawthorne first. Then a list of his major works, their themes and outlines. It also includes a detailed discussion about the styles and techniques used by him. The themes, symbols and the structure of The Scarlet Letter are discussed next, followed by the list of major as well as minor characters. This unit concludes with a discussion about Hawthorne’s contribution to American literature and a set of questions. Lastly there is a list of further readings of Hawthorne to gain knowledge about the critical aspects of the novel. -

Introduction to College Composition

Introduction to College Composition Introduction to College Composition Lumen Learning CONTENTS Reading: Types of Reading Material ...........................................................................................1 • Introduction: Reading......................................................................................................................................... 1 • Outcome: Types of Reading Material ................................................................................................................ 2 • Comparing Genres, Example 1 ......................................................................................................................... 2 • Comparing Genres, Example 2 ......................................................................................................................... 4 • Comparing Genres, Example 3 ......................................................................................................................... 5 • Comparing Genres, Example 4 ......................................................................................................................... 6 • Comparing Genres, Example 5 ......................................................................................................................... 7 • Comparing Genres, Conclusion......................................................................................................................... 9 • Self Check: Types of Reading ........................................................................................................................ -

THE ATHEISM of MARK TWAIN: the EARLY YEARS THESIS Presented

37c A:) 2 THE ATHEISM OF MARK TWAIN: THE EARLY YEARS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Wesley Britton, B.A. Denton, Texas April, 1986 Britton, Wesley A. , The Atheism of Mark Twain: The Early Years. Master of Arts (English),, Augustj198 6 , 73 pp. , bibliography 26 titles. Many Twain scholars believe that his skepticism was based on personal tragedies of later years. Others find skepticism in Twain's work as early as The Innocents Abroad. This study determines that Twain's atheism is evident in his earliest writings. Chapter One examines what critics have determined Twain's religious sense to be. These contentions are dis- cussed in light of recent publications and older, often ignored, evidence of Twain' s atheism. Chapter Two is a biographical look at Twain's literary, family, and community influences, and at events in Twain's life to show that his religious antipathy began when he was quite young. Chapter Three examines Twain's early sketches and journalistic squibs to prove that his voice, storytelling techniques, subject matter, and antipathy towards the church and other institutions are clearly manifested in his early writings. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTIO. .... .. .. .. .. .. .. Chapter I. THE CRITICAL BACKGROUND . .. .. .. 7 ... .- .- .-- .- .* .- --26 II, BIOGRAPHY - III. THE EARLY WRITINGS . .44 CONCLUSION .. ,. 0. , . .. 09. .. ... 67 BIBLIOGRAPHY. .. .. .. .0. .a.071 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this study is to demonstrate that from a very early age, Samuel Langhorn Clemens had no strong religious convictions, and that, indeed, for most of his life, he was an atheist. -

Adventure Time Princess Day Dvd

Adventure time princess day dvd click here to download Cartoon Network: Adventure Time - Princess Day (V7). Oh My GLOB! It's practically princess overload in Cartoon Networks latest release Adventure Time: Princess Day. Featuring fan favorite leading royal lady Lumpy Space Princess on the amaray, this is the 7th Adventure Time volume releasing with 16 full episodes. DVD Summary: Oh My GLOB! It's practically princess overload in Cartoon Networks latest release Adventure Time: Princess Day. Featuring fan favorite leading royal lady Lumpy Space Princess on the amaray, this is the 7th Adventure Time volume releasing with 16 full episodes. Adventure Time: Princess Day releases just. Even though it is Princess Day, not every princess in the series appeared in the episode. This episode was released on DVD before it aired on TV. Marceline is shown holding a bottle of sunscreen in the promotional artwork and in her first appearance in the episode, which explains why she was unharmed in the morning. Oh My Glob! So. Many. Princesses!!! Check out this royalty-filled clip from the all-new Princess Day episode. Princess Day” is a fun episode, but it's especially notable for two specific reasons. To start, the episode was released on home video two days ago as part of a DVD compilation, the first time Cartoon Network has released an episode on video before airing it. It's also the first episode—not including the. Cartoon Network is at it again with another cartoon collection aimed at undiscerning fans who NEED some episodes NOW and are not concerned about bonus features and complete season sets and story continuity. -

Petrified Profound Verdict Invariable Depravity Benevolent Negligence

Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum Lesson or Unit Plan for “Authority and Power” Created by: Brad Peuster School: Fort Zumwalt East High School City, State: St. Peters, MO Mark Twain Teachers’ Workshop, July 14, 2017 Hannibal, Missouri “Authority and Power with the Media and President” LESSON or UNIT PLAN for “Authority and Power” Concept or Topic: Suggested Grade Level(s)/Course: Authority and Power with the Media and Resource or Modified: Government 11th the President Grade (Special Education Setting) Subject: Suggested Time Frame: U.S. Government: Resource 3 days (50 minutes each day) Objective(s): 1) Students will create a fake news story and then explain and list why it is a fake story, giving supporting details of what makes theirs a fake news story, scoring at least 7 out of 10 possible points on the scoring guide. 2) Students will create a list of at least 5 characteristics/skills or abilities in a Presidential Candidate and explain why each is important to being President. 3) Students will be able to explain and give detailed examples of what makes a person an Authority. Students will create a statement explaining in what area they are an expert, and then give 3 supporting details going into depth specifically explaining those 3 details and showing their mastery. Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.2.D Use precise language and domain-specific vocabulary to manage the complexity of the topic Social Studies Missouri Learning Standard: MLS Code: 9-12 G.V.3 G.S. Grade 9-12, Course GV, Course: Government, Theme 3, Strand GS (number 372) -Analyze the unique roles and responsibilities of the three branches of government to determine how they function and interact. -

A Connecticut Yankee in Utopia: Mark Twain Between Past, Present and Future

Scuola Dottorale di Ateneo Graduate School Dottorato di ricerca in Lingue, Culture e Società Moderne Ciclo XXIX Anno di discussione 2017 A Connecticut Yankee in Utopia: Mark Twain Between Past, Present and Future SETTORE SCIENTIFICO DISCIPLINARE DI AFFERENZA: L-LIN/11 Tesi di Dottorato di Nicholas Stangherlin, matricola 819747 Coordinatore del Dottorato Tutore del Dottorando Prof. Enric Maqueda Bou Prof.ssa Pia Masiero Nicholas Stangherlin, Università Ca’ Foscari Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... p.5 Chapter 1. Twain’s Speculations on Civilization and Progress ..................................................... p.21 I. The Paige Typesetter-Conversion Narrative and Hank’s Idea of Progress ................. p.22 II. “Cannibalism in The Cars” and “The Great Revolution in Pitcairn:” Butterworth Stavely as a Prototype for Hank Morgan ..................................................................... p.27 III. Anti-Imperialism and The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts...................................... p.35 IV. Science, Capitalism and Slavery in “The Secret History of Eddypus” and “Sold To Satan.” ......................................................................................................... p.38 Chapter 2. Content and Tensions of Utopian Fiction ..................................................................... p.45 I. An Age of Fear and Invention..................................................................................... -

Adventure Time with Fionna & Cake Free

FREE ADVENTURE TIME WITH FIONNA & CAKE PDF Natasha Allegri,Pendleton Ward | 176 pages | 29 Oct 2013 | Kaboom | 9781608863389 | English | Los Angeles, Calif., United States Adventure Time With Fionna & Cake - Gutter Pop Comics Fionna previously spelled Fiona and also known as Fionna the Human is an in-universe fictional character and the gender-swapped version of Finn who was created by the Ice King in his fan-fiction from a strange red glowing inspiration during Ice King's sleep. In the real world, she was created by series character designer Natasha Allegri in a series of web comics and drawings. She and the other gender-swapped characters appeared occasionally in their own segment of the show. She is usually seen in the company of Cakeher own stretchy companion and also adoptive sister. Fionna's nemesis is the Ice Queen. Ice King fantasizes about one day making her real and marrying her. While usually appearing as black dots, her eyes are seen as blue when enlarged. She wears a rabbit-themed hat similar to Finn's bear-themed hat with exposed locks of blonde hair and also has teeth missing in Adventure Time with Fionna & Cake similar fashion to Finn. Unlike Finn, her neck Adventure Time with Fionna & Cake blonde hair are shown. She Adventure Time with Fionna & Cake has buck teeth in several episodes, fitting with her rabbit hat. When she is not wearing her hat, her hair goes down to between her knees and ankles. Her outfit includes a teal blue shirt with elbow-length sleeves, a dark blue skirt, and over-the-knee socks with two thin, light blue horizontal stripes at the top.