The Wondrous Bird's Nest I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commentary V2 Proofed FINAL

!1 Sonic autoethnographies: six | records | of | the | listening | self Iain Findlay-Walsh Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Music (Composition) School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow February 2016 !2 Portfolio contents 1. Commentary (including portfolio on USB flash drive) 2. plastic 2 x CD case - corresponding to postface 3. 1 x CD wrapped in packing tape - corresponding to In Posterface: 1 4. 12” art print in PVC sleeve - corresponding to Somehere in 5. removable vinyl sticker - corresponding to _omiting in the changing room !3 Acknowledgements Thanks to Louisa-Jane, Blue and Bon Findlay-Walsh for providing the support and space to develop and complete this work. Thanks to Nick Fells and Martin Parker Dixon, who supervised throughout the project. Thanks to the following for supporting me in this work, providing opportunities to test and present parts of it, and contributing to the ideas and practice. Alasdair Campbell, Clare McFarlane, Tristan Partridge, John Campbell, May Campbell, Ruth Campbell, FK Alexander, Rob Alexander, Nick Anderson, Calum Beith, Rosana Cade, Liam Casey, Martin Cloonan, Lewis Cook, Carlo Cubero, Euan Currie, Anne Danielsen, Neil Davidson, Barry Esson, Stuart Evans, Paul Gallagher, Mark Grimshaw, Louise Harris, Paul Henry, Fielding Hope, Katia Isakoff, Bryony McIntyre, Emily McLaren, Jamie McNeill, Rickie McNeill, Felipe Otondo, Dale Perkins, Emily Roff, Calum Scott, Toby Seay, Sam Smith, Craig Tannoch, Rupert Till, Fritz Welch, Simon Zagorski-Thomas. !4 Abstract This commentary accompanies a portfolio of pieces which combine soundscape composition and record production methods with aspects of autoethnographic practice. This work constitutes embodied research into relations between everyday auditory experience, music production and reception, and selfhood. -

HECUBA by Euripides

HECUBA by Euripides translated by Jay Kardan and Laura-Gray Street POLYDORUS HECUBA CHORUS POLYXENA ODYSSEUS TALTHYBIUS THERAPAINA AGAMEMNON POLYMESTOR Script copyright Jay Kardan and Laura-Gray Street. Apply to the authors for performance permissions. Hecuba — translated by Kardan and Street — in Didaskalia 8 (2011) 32 POLYDORUS I come from bleakest darkness, where corpses lurk and Hades lives apart from other gods. I am Polydorus, youngest son of Hecuba and Priam. My father, worried Troy might fall to Greek offensives, sent me here, to Thrace, my mother’s father’s home and land of his friend Polymestor, who controls this rich plain of the Chersonese and its people with his spear. My father sent a large stash of gold with me, to insure that, if Ilium’s walls indeed (10) were toppled, I’d be provided for. He did all this because I was too young to wear armor, my arms too gangly to carry a lance. As long as the towers of Troy remained intact, and the stones that marked our boundaries stood upright, and my brother Hector was lucky with his spear, I thrived living here with my father’s Thracian friend, like some hapless sapling. (20) But once Troy was shattered—Hector dead, our home eviscerated, and my father himself slaughtered on Apollo’s altar by Achilles’ murderous son— then Polymester killed me. This “friend” tossed me dead into the ocean for the sake of gold, so he could keep Priam’s wealth for himself. My lifeless body washes ashore and washes back to sea with the waves’ endless ebb and flow, and remains unmourned, unburied. -

The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2021 The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival Gabriel Bugarin Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bugarin, Gabriel, "The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival" (2021). WWU Graduate School Collection. 1034. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/1034 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival By Gabriel Bugarin Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts ADVISORY COMMITTEE Dr. Kathryn Trueblood, Chair Dr. Jane Wong Dr. Chris Loar GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

Metonymy & Trauma

ii METONYMY & TRAUMA RE-PRESENTING DEATH IN THE LITERATURE OF W. G. S E B A L D Andrew Michael Watts A research dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD English University of New South Wales 2006 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: WATTS First name: ANDREW Other names: MICHAEL Abbreviation for degree as given in the University Calendar: PhD School: ENGLISH Faculty: ARTS Title: Metonymy & Trauma: Re-presenting Death in the Literature of W. G. Sebald Abstract 350 words maximim: (PLEASE TYPE) Novel: Fragments of a Former Moon The novel Fragments of a Former Moon (FFM) invokes the paradoxical earlier death of the still-living protagonist. The unmarried German woman is told that her skeletal remains have been discovered in Israel, thirty-eight years since her body was interred in 1967. This absurd premise raises issues of representing death in contemporary culture; death's destabilising effect on the individual's textual representation; post-Enlightenmentdissolution of the modern rational self; and problems of mimetic post- Holocaust representation. Using W G Sebald's fiction as a point of departure, FFM's photographic illustrations connote modes of textual representation that disrupt the autobiographical self, invoking mortality and its a-temporal (representational) displacement. As with Sebald's recurring references to the Holocaust, FFM depicts a psychologically unstable protagonist seeking to recover repressed memories of an absent past. Research dissertation: Metonymy &Trauma: Re-presenting Death in the Literature of W. G. Sebald The dissertation centres on the effect of metonymy in the rhetoric of textually-constructedidentity and its contemporary representation in the face of death. -

Volume 8, No. 2 Issue 22

Volume 8, No. 2 Issue 22 ©2021 Typehouse Literary Magazine. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced in any form without written permission. Typehouse Literary Magazine is published triannually. Established 2013. Typehouse Literary Magazine Editor in Chief: Val Gryphin Senior Editors: Nadia Benjelloun (Prose) Lily Blackburn (Craft Essay) Jiwon Choi (Poetry) Mariya Khan (Prose and Poetry) Yukyan Lam (Prose) Jared Linder (Prose) Kameron Ray Morton (Prose) Alan Perry (Poetry) Trish Rodriguez (Prose) Kate Steagall (Prose) T. E. Wilderson (Prose) Associate Editors: Sally Badawi (Prose and Poetry) Charlotte Edwards (Prose) Teddy Engs (Prose) Jody Gerbig (Prose) Erin Karbuczky (Prose) Typehouse is a writer-run literary magazine based out of Portland, Oregon. We are always looking for well-crafted, previously unpublished writing and artwork that seeks to capture an awareness of the human condition. To learn more about us, visit our website at www.typehousemagazine.com. Cover Artwork: Jay and Turkey II, 24" x 36,” Acrylic on Canvas, from The Three Jay and Turkey Paintings by Elizabeth Eve King (E.E. King) (see page 49). Table of Contents Fiction: The Soap Carver Ryan Doskocil 2 Last Lost Boy Sara Herchenroether 14 Later Is One of Our Tags Jessica Evans 28 Nothing Ha-Ha Funny at the Edge of the Light Esem Junior 32 With Love, From Waystation 4 Brittany J. Smith 54 Zombie Kate Wendy Elizabeth Wallace 76 Lilac Boy Christopher Barker 81 That Changes Everything Naira Wilson 94 The Time Spider David Evan Krebs 104 Takahashi -

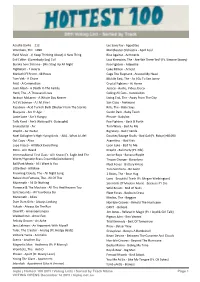

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft. -

The Beautiful Struggle: an Analysis of Hip-Hop Icons, Archetypes and Aesthetics

THE BEAUTIFUL STRUGGLE: AN ANALYSIS OF HIP-HOP ICONS, ARCHETYPES AND AESTHETICS ________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ________________________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ________________________________________________________________________ by William Edward Boone August, 2008 ii © William Edward Boone 2008 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT The Beautiful Struggle: an Analysis of Hip-Hop Icons, Archetypes and Aesthetics William Edward Boone Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Nathaniel Norment, Ph.D. Hip hop reached its thirty-fifth year of existence in 2008. Hip hop has indeed evolved into a global phenomenon. This dissertation is grounded in Afro-modern, Afrocentric and African-centered theory and utilizes textual and content analysis. This dissertation offers a panoramic view of pre-hip hop era and hip hop era icons, iconology, archetypes and aesthetics and teases out their influence on hip hop aesthetics. I identify specific figures, movements and events within the context of African American and American folk and popular culture traditions and link them to developments within hip hop culture, iconography, and aesthetics. Chapter 1 provides an introduction, which includes a definition of terms, statement of the problem and literature review. It also offers a perfunctory discussion of hip hop -

BUSINESS [9^ Shultz to Set Groundwork for Summit

to - MANCHESTER HERALD. Tuesday. July 30, 1985 MANCHESTER FOCUS U.S./W ORLD WEATHER \ BUSINESS MMH census stable Barbecues to go: Speculation increases Heavy rains tonight; after decline in 1984 Try these recipes on Gemayel’s ouster clearing Thursday ... page 2 Business In Brief Car buyers beware ... page 3 ... page 11 ... page 5 Balloon loans are risky alternative owe money if the bank determines that you put on too If you’re in the market for a car, have you been much mileage (a sticky question at best) or didn t asked if you would like to buy with a "balloon loan"? maintain it in top shape. ^ ^ .ho* This type of loan is being actively promoted these The central point; Don’t be fooled by the pitch that days because, with a balloon, you can buy a more Your you can buy more car with a balloon loan. M p r a l J i expensive car than you could with conventional Money's "You’re opening yourself to significant risk, says MmthtBtn financing — and you may not be fully aware that three Stephen Brobeck, executive director of the Consumer ......... * \AyorlnAftdfl\/Wednesday, JiiK July 31. 1985 — Single copy: 25C or four years in the future, you must come up with the Federation of America. "Generally speaking, if you Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm balloon or forfeit the car. Worth can’t afford a traditional installment loan, you won t Balloon auto loans closely resemble balloon Sylvia Porter be able to afford a balloon loan.” mortgages: You pay lower monthly installments, but Consider: Most owners keep cars for around eight at the loan’s maturity you must come up with a large years. -

Red Mesa Review 2019

RED MESA REVIEW 2019 Red Mesa Review 1 Red Mesa Review Collective Yi-Wen Huang Carmela Lanza Thomas McLaren Marilee Petranovich Keri Stevenson Kristi Wilson Red Mesa Review - Representing the varied voices of the West Central Plateau and the Four Corners Region. Justin House ‘Knockoff Textile” (Cover Photo) Photography Red Mesa Review 2 Contents Art: “Knockoff Textile” Justin House “Dream Catcher” Corine Lei Gonzales “Sacred” Maya Ross “Untitled” Jose Alfonso Dominguez Apura “The Four Elements” Clyde Hillis II “Lupton” Ashley Miller “Day Dreaming” Clyde Hillis II “Traditional Outfit” Ashley Miller “Skeleton” Maya Ross “Abstract Brooch” Larson Barney “Nature’s Reject” Kayla Vigil “Good Luck Necklace” Monte T. Thompson “Tea Pot” Ashley Miller “Undeviating” Justin House “Bigfoot Makin’ that Noise!” Nick Brokeshoulder “Window Rock” Corine Lei Gonzales “Protective Test” Justin House “Untitled” Jose Alfonso Dominguez Apura Creative Non-Fiction: “Don’t Fear the Buckskin” Llewellyn Paul “Meddling in a Crossfire” Kayla Vigil “Morning Lesson” Kawther Soufan “In A Narrow Canyon” Paige Laughing “Primal Scream” Katie Schultz “”The Struggle of Being Fashionably Broke” Gyla Tipgos “Time Is An Illusion” Peyton Alex “ ‘The Yet-so Fed Us’: Navajo Encounters with a Living Primate” Christopher Dyer “A Bump in the Night” Harrietta Begay Fiction: “A Tale of a Navajo Warrior” Colleen Yazzie Poetry: “Electric” Kyler Edsitty “Sun in Leo” Kyler Edsitty “Blue” Kyler Edsitty “Can You Understand Me?” Mikayla Gamble “Life Rules” Florentin Smarandache “Deconstruction in Action” Tom McLaren “Desert Life” Marcella Garcia “Au Lectur To The Reader B2B Bad Romance” Tom McLaren “Sun” Alexis Leekela Red Mesa Review 3 “You” Alexis Leekela “Spring” Alexis Leekela “I Am Yours When I Find You” Cobin Bo Willie “I Sing The Body Electric” Tom McLaren “Language In My Mouth” Carmela Delia Lanza “Living With Crows” Keri Stevenson “Love Yourself” Mikayla Gamble “ ‘Plight of the Pummeled’ Strength in Struggle . -

The Stars and Teeth

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this St. Martin’s Press ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. To Mom and Dad— For your love, eternal support, and for waiting in the hot sun every time I dragged you to a million book signings. I wouldn’t be here without you … literally. To Taylor— Because we finally did it. ARIDA Island of soul magic Represented by sapphire VALUKA Island of elemental magic Represented by ruby MORNUTE Island of enchantment magic Represented by rose beryl CURMANA Island of mind magic Represented by onyx KEROST Island of time magic Represented by amethyst SUNTOSU Island of restoration magic Represented by emerald ZUDOH Island of curse magic Represented by opal CHAPTER ONE This day is made for sailing. The ocean’s brine coats my tongue and I savor its grit. Late summer’s heat has beaten the sea into submission; it barely sways as I stand against the starboard ledge. Turquoise water stretches into the distance, stuffed full of blue tangs and schools of yellowtail snapper that flounder away from our ship and conceal themselves beneath thin layers of sea foam. -

Not Vanishing Chrystos

1 American Studies Collections kjU Ethnic Studies Libraiy 30 Stephens Hall #2360 Because there are so many myths & misconceptions about Native © 1988 Chrystos University of California Berkeley, CA 94720-2360 people, it is important to clarify myself to the reader who does not Kj At ^ know me. I was not bom on the reservation, but in San Francisco, part of a group called “Urban Indians” by the government. I grew up around Black, Latin, Asian & white people & am shaped by that experience, as well as by what my father taught me. He had been I This book may not be reproduced in part or in whole by any means taught to be ashamed & has never spoken our language to me. Much 1 without written permission from the Publisher, except for the use of of the fury which erupts from my work is a result of seeing the pain | short passages for review purposes. All correspondence to the Author that white culture has caused my father. It continues to give pain to all should be addressed to Press Gang Publishers. of us. I am not the “Voice” of Native women, nor representative of Native women in general. I am not a “Spiritual Leader,” although many white women have tried to push me into that role. While I am Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data deeply spiritual, to share this with strangers would be a violation. Our rituals, stories & religious practices have been stolen & abused, as has Chrystos, 1946- our land. I don’t publish work which would encourage this—so you Not vanishing will find no creation myths here. -

How African American Males (Re) Construct Their Identities, Self-Presentations, and Relationships Offline and Online

Performing Self through Social Media: How African American Males (Re) Construct Their Identities, Self-Presentations, and Relationships Offline and Online DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ronald L. Parker, B.S., M.A. Graduate Program in Educational Policy and Leadership The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard J. Voithofer, Ph.D., Advisor & Co-Chair James L. Moore, III, Ph.D., Co-Chair Osei Appiah, Ph.D. Copyrighted by Ronald L. Parker 2015 Abstract This qualitative study investigated how adult African American undergraduate males at a predominantly white institution (PWI) (re)constructed their identity, self- presentation, and relationships on Facebook (www.facebook.com), a popular social network site (SNS). The results of the study provided insight into how undergraduate African American males integrated their internal and external self and social media to construct and represent “who they are” on-campus and on this particular social network site. In addition, the results revealed how the participants created, managed, and facilitated their relationships in both environments, while providing useful insights into how they endured the historically negative images that have tried to define this population. Grounded theory methods including constant comparison analysis, were used to interpret the interview and supportive data from twenty-one (21) undergraduate African American male participants