Commentary V2 Proofed FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helena Mace Song List 2010S Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don't You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele

Helena Mace Song List 2010s Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don’t You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele – One And Only Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Adele- Skyfall Adele – Someone Like You Birdy – Skinny Love Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga - Shallow Bruno Mars – Marry You Bruno Mars – Just The Way You Are Caro Emerald – That Man Charlene Soraia – Wherever You Will Go Christina Perri – Jar Of Hearts David Guetta – Titanium - acoustic version The Chicks – Travelling Soldier Emeli Sande – Next To Me Emeli Sande – Read All About It Part 3 Ella Henderson – Ghost Ella Henderson - Yours Gabrielle Aplin – The Power Of Love Idina Menzel - Let It Go Imelda May – Big Bad Handsome Man Imelda May – Tainted Love James Blunt – Goodbye My Lover John Legend – All Of Me Katy Perry – Firework Lady Gaga – Born This Way – acoustic version Lady Gaga – Edge of Glory – acoustic version Lily Allen – Somewhere Only We Know Paloma Faith – Never Tear Us Apart Paloma Faith – Upside Down Pink - Try Rihanna – Only Girl In The World Sam Smith – Stay With Me Sia – California Dreamin’ (Mamas and Papas) 2000s Alicia Keys – Empire State Of Mind Alexandra Burke - Hallelujah Adele – Make You Feel My Love Amy Winehouse – Love Is A Losing Game Amy Winehouse – Valerie Amy Winehouse – Will You Love Me Tomorrow Amy Winehouse – Back To Black Amy Winehouse – You Know I’m No Good Coldplay – Fix You Coldplay - Yellow Daughtry/Gaga – Poker Face Diana Krall – Just The Way You Are Diana Krall – Fly Me To The Moon Diana Krall – Cry Me A River DJ Sammy – Heaven – slow version Duffy -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Plunderphonics – Plagiarismus in Der Musik

Plagiat und Fälschung in der Kunst 1 PLUNDERPHONICS – PLAGIARISMUS IN DER MUSIK PLUNDERPHONICS – PLAGIARISMUS IN DER MUSIK Durch die Erfindung der Notenschrift wurde Musik versprachlicht und damit deren Beschreibung mittelbar. Tonträger erlaubten es, Interpretationen, also Deutungen dieser sprachlichen Beschreibung festzuhalten und zu reproduzieren. Mit der zunehmenden Digitalisierung der Informationen und somit der Musik eröffneten sich im 20. Jahrhundert neue Möglichkeiten sowohl der Schaffung als auch des Konsums der Musik. Eine Ausprägung dieses neuen Schaffens bildet Plunderphonics, ein Genre das von der Reproduktion etablierter Musikstücke lebt. Diese Arbeit soll einen groben Überblick über das Genre, deren Ursprünge und Entwicklung sowie einigen Werken und thematisch angrenzenden Musik‐ und Kunstformen bieten. Es werden rechtliche Aspekte angeschnitten und der Versuch einer kulturphilosophischen Deutung unternommen. 1.) Plunderphonics und Soundcollage – Begriffe und Entstehung Der Begriff Plunderphonics wurde vom kanadischen Medienkünstler und Komponisten John Oswald geprägt und 1985 in einem bei der Wired Society Electro‐Acoustic Conference in Toronto vorgetragenen Essay zuerst verwendet [1]. Aus musikalischer Sicht stellt Plunderphonics hierbei eine aus Fragmenten von Werken anderer Künstler erstellte Soundcollage dar. Die Fragmente werden verfälscht, beispielsweise in veränderter Geschwindigkeit abgespielt und neu arrangiert. Hierbei entsteht ein Musikstück, deren Bausteine zwar Rückschlüsse auf das „Ursprungswerk“ erlauben, dessen Aussage aber dem „Original“ zuwiderläuft. Die Verwendung musikalischer Fragmente ist keine Errungenschaft Oswalds. Viele Musikstile bedienen sich der Wiederaufnahme bestehender Werke: Samples in populär‐ und elektronischer Musik, Riddims im Reggae, Mash‐Ups und Turntablism in der Hip‐Hop‐Kultur. Soundcollagen, also Musikstücke, die vermehrt Fragmente verwenden, waren mit dem Fortschritt in der Tontechnik möglich geworden und hielten Einzug in den Mainstream [HB2]. -

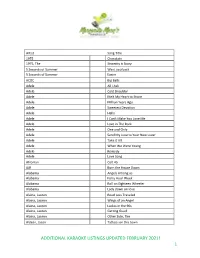

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Joe Matheny, a Founding Father Culture Jammer, Was Kind Enough to Give What He Called His "Last Interview" Online to Escape

9/11/2014 escape.htm Joe Matheny, a founding father Culture Jammer, was kind enough to give what he called his "last interview" online to Escape. Now happily working towards his pension in an anonymous programmer's job, Joe famously spammed the White House with a bunch of email frogs and caused uproar in American media society with his many japes. But why did it get all serious? And why are none of the original CJers talking to each other? What follows is the unedited version of the interview published in December 1997's Escape. All the hotlinks are Joe's. So who started Culture Jamming as a phenomenon, and why? Boy, that's a loaded question! No, really. It depends on who you ask. Personally I trace the roots of media pranking, or "culture jamming" as it's known these days, to people like Orson Welles and his famous "War of the Worlds" broadcast in America, or even his lesser known film "F is for Fake". More recently, a scientist by the name of Harold Garfinkle conducted something called breaching experiments, in which he studied the flexbility of peoples belief systems by fabricating stories and then guaging peoples reaction to them.He called this field of study Ethnomethodology and popularized it in his book Studies in Ethnomethodology. Garfinkle would incrementally make the his stories wilder and more speculative until the subjects would finally reach a point of disbelief. (in other words Garfinkle perpetrated lies, and then "pushed the envelope" with his subjects) In the 60s CJ was taken to a whole new level by two very differnet groups. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Box London www.karaokebox.co.uk 020 7329 9991 Song Title Artist 22 Taylor Swift 1234 Feist 1901 Birdy 1959 Lee Kernaghan 1973 James Blunt 1973 James Blunt 1983 Neon Trees 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince If U Got It Chris Malinchak Strong One Direction XO Beyonce (Baby Ive Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Cant Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Everybody's Gotta Learn Sometime) I Need Your Loving Baby D (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Wont You Play) Another Somebody… B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The World England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina And The Diamonds (I Love You) For Sentinmental Reasons Nat King Cole (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (Ill Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Reflections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Keep Feeling) Fascination The Human League (Maries The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Meet) The Flintstones B-52S (Mucho Mambo) Sway Shaft (Now and Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Sittin On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (The Man Who Shot) Liberty Valance Gene Pitney (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We Want) The Same Thing Belinda Carlisle (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1 2 3 4 (Sumpin New) Coolio 1 Thing Amerie 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus -

Helter Skelter” and Sixties Revisionism “Helter Skelter” Et L'héritage Polémique Des Années 1960

Volume ! La revue des musiques populaires 9 : 2 | 2012 Contre-cultures n°2 “Helter Skelter” and Sixties Revisionism “Helter Skelter” et l'héritage polémique des années 1960 Gerald Carlin and Mark Jones Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/volume/3407 DOI: 10.4000/volume.3407 ISSN: 1950-568X Printed version Date of publication: 15 December 2012 Number of pages: 34-49 ISBN: 978-2-913169-33-3 ISSN: 1634-5495 Electronic reference Gerald Carlin and Mark Jones, « “Helter Skelter” and Sixties Revisionism », Volume ! [Online], 9 : 2 | 2012, Online since 15 June 2014, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/volume/3407 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/volume.3407 This text was automatically generated on 10 December 2020. L'auteur & les Éd. Mélanie Seteun “Helter Skelter” and Sixties Revisionism 1 “Helter Skelter” and Sixties Revisionism “Helter Skelter” et l'héritage polémique des années 1960 Gerald Carlin and Mark Jones EDITOR'S NOTE This text was published in Countercultures & Popular Music (Farnham, Ashgate, 2014), while its French translation appeared in this issue of Volume! in 2012. “Helter Skelter” and the End of the Sixties Volume !, 9 : 2 | 2012 “Helter Skelter” and Sixties Revisionism 2 1 In late August 1968, within a few days of each other, new singles were released by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. The unusual proximity of release dates by the world’s two most significant rock bands was echoed by the congruity of the songs’ themes: the Stones’ “Street Fighting Man” and the Beatles’ “Revolution” were both responses to the political unrest and protest which characterised the spring and summer of 1968. -

2. Mondo 2000'S New Media Cool, 1989-1993

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The web as exception: The rise of new media publishing cultures Stevenson, M.P. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stevenson, M. P. (2013). The web as exception: The rise of new media publishing cultures. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 2. Mondo 2000’s new media cool, 1989-1993 To understand how it was possible for the web to be articulated as an exceptional medium when it surfaced in the 1990s - that is, as a medium that would displace its mass and mainstream predecessors while producing web-native culture - one must see the historical and conceptual ties between web exceptionalism and cyberculture. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

CORPORATE OFFICE Level 1 32 Oxford Terrace Telephone: 0064 3 364 4160 Christchurch Central Fax: 0064 3 364 4165 CHRISTCHURCH 8011 [email protected]

CORPORATE OFFICE Level 1 32 Oxford Terrace Telephone: 0064 3 364 4160 Christchurch Central Fax: 0064 3 364 4165 CHRISTCHURCH 8011 [email protected] 15 June 2021 9(2)(a) RE Official Information Act request CDHB 10600 I refer to your email dated 6 May 2021 requesting the following information under the Official Information Act from Canterbury DHB regarding vaccine misinformation. Specifically: • Since February 1 2021, copies of any reports, documents, memoranda, and correspondence, both internal and external, regarding misinformation about Covid-19 vaccines/vaccination, including any reports of examples of misinformation, any official reaction to such examples or the problem of misinformation as a whole, and the possible impact of such misinformation. Please refer to Appendix 1 (attached) for correspondence (both internal and external) regarding misinformation about Covid-19 vaccines/vaccination. Note: we have redacted information under the following sections of the Official Information Act. Section 9(2)(a) – “….to protect the privacy of natural persons, including those deceased”. Section 9(2)(b)(ii) “…to protect the commercial position of the person who supplied the information, or who is the subject of the information”. Section 9(2)(g)(i) “… to maintain the effective conduct of public affairs through the free and frank expression of opinions.” We have also removed information we believe to be ‘Out of scope’ of your request. I trust this satisfies your interest in this matter. You may, under section 28(3) of the Official Information Act, seek a review of our decision to withhold information by the Ombudsman. Information about how to make a complaint is available at www.ombudsman.parliament.nz; or Freephone 0800 802 602. -

'Titanium' | David Guetta (Feat. Sia)

‘Titanium’ David Guetta (feat. Sia) ‘Titanium’ | David Guetta (feat. Sia) ‘Titanium’ was a number one hit for French DJ and music producer David Guetta, featuring vocals from Australian singer Sia. Initially released digitally as one of four promotional singles for the album Nothing but the Beat in August 2011, the hit was o!cially released as the fourth single from the album in December of that same year. ‘Titanium’ was well received in many of the top music markets worldwide, achieving number 1s in four countries and top 10s in an incredible twenty "ve countries across the globe. #e single was met with positive reviews, with many claiming it to be the show stopper of the album thanks to Sia’s collaboration on lyrics and phenomenal vocal performance. Described as “epic and energising”, ‘Titanium’ was musically likened to the works of Coldplay and Sia’s vocal was compared to that of Fergie. Many reviewers raved about Sia’s delivery of the song’s hook, stating that ‘Titanium’ was by far the “most intriguing hook-up” of Guetta’s "$h studio album. #e single was certi"ed 3 x Platinum in the UK with sales just short of two million copies, and 2 x Platinum in the US with four million records sold. Guetta’s album Nothing But !e Beat topped the album charts in the DJ’s home nation of France, as well as Australia, Belgium, Germany, Spain and Switzerland. While some reviewers felt it was lacking somewhat in comparison to his earlier works, the album was well-received by many with tracks ‘Night of Your Life’ and ‘Titanium’ being highlighted as the strongest on the release. -

Karaoke-Katalog Update Vom: 17/06/2020 Singen Sie Online Auf Gesamter Katalog

Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 17/06/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Dance Monkey - Tones and I Rote Lippen soll man küssen - Gus Backus Amoi seg' ma uns wieder - Andreas Gabalier Perfect - Ed Sheeran Tears In Heaven - Eric Clapton Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens My Way - Frank Sinatra You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Angels - Robbie Williams 99 Luftballons - Nena Up Where We Belong - Joe Cocker Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Zombie - The Cranberries All of Me - John Legend Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch New York, New York - Frank Sinatra Blinding Lights - The Weeknd Niemals In New York Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Creep - Radiohead EXPLICIT Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Let It Be - The Beatles Always Remember Us This Way - A Star is Born Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer A Million Dreams - The Greatest Showman Kuliko Jana, Eine neue Zeit - Oonagh Eine Nacht - Ramon Roselly In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley (Everything I Do) I Do It For You - Bryan Adams Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Egal - Michael Wendler Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Der hellste Stern (Böhmischer Traum) - DJ Ötzi Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Uber den Wolken - Reinhard Mey Losing My Religion - R.E.M.