Burn Magazine and Respective Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT “Our Grand Narrative of Women and War”: Writing, And

ABSTRACT “Our Grand Narrative of Women and War”: Writing, and Writing Past, a Gendered Understanding of War Front and Home Front in the War Writing of Hemingway, O’Brien, Plath, and Salinger Julie Ooms, Ph.D. Mentor: Luke Ferretter, Ph.D. Scholars and theorists who discuss the relationship between gender and war agree that the divide between the war front and the home front is gendered. This boundary is also a cause of pain, of misunderstanding, and of the breakdown of community. One way that soldiers and citizens, men and women, on either side of the boundary can rebuild community and find peace after war is to think—and write—past this gendered understanding of the divide between home front and war front. In their war writing, the four authors this dissertation explores—Ernest Hemingway, Tim O’Brien, Sylvia Plath, and J.D. Salinger—display evidence of this boundary, as well as its destructive effects on persons on both sides of it. They also, in different ways, and with different levels of success, write or begin to write past this boundary and its gendered understanding of home front and war front. Through my exploration of these four authors’ work, I conclude that the war writers of the twentieth century have a problem to solve: they still write within an understanding of war that very clearly genders combatants and noncombatants, warriors and home front helpers. However, they also live and write within a historical and political era that opens up a greater possibility to think and write past this gendered understanding. -

Abstract Why We Turn the Page: a Literary Theory Of

ABSTRACT WHY WE TURN THE PAGE: A LITERARY THEORY OF DYNAMIC STRUCTURALISM Justin J. J. Ness, Ph.D. Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2019 David J. Gorman, Director This study claims that every narrative text intrinsically possesses a structure of fixed relationships among its interest components. The progress of literary structuralism gave more attention to the static nature of what a narrative is than it did to the dynamic nature of how it operates. This study seeks to build on the work of those few theorists who have addressed this general oversight and to contribute a more comprehensive framework through which literary critics may better chart the distinct tensions that a narrative text cultivates as it proactively produces interest to motivate a reader’s continued investment therein. This study asserts that the interest in narrative is premised on three affects— avidity, anxiety, and curiosity—and that tensions within the text are developed through five components of discourse: event, description, dialog, sequence, and presentation. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DEKALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2019 WHY WE TURN THE PAGE: A LITERARY THEORY OF DYNAMIC STRUCTURALISM BY JUSTIN J. J. NESS ©2019 Justin J. J. Ness A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Dissertation Director: David J. Gorman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Gorman, the director of my project, introduced me to literary structuralism six years ago and has ever since challenged me to ask the simple questions that most people take for granted, to “dare to be stupid.” This honesty about my own ignorance was—in one sense, perhaps the most important sense—the beginning of my life as a scholar. -

CASS CITY CHRONICLE I

CASS CITY CHRONICLE d tTI [ • ' Ul=: ~ I I ir i H~-~_ .... VOLUME 29,' NUMBER 2. CASS CITY, MICHIGAN, FRIDAY, APRIL 20, 1934. EIGHT PAGES. ] I Prayer and offering 4-H ACHIEVEMENT DAYS. COUNCIL NAMED MAY 14-15 March, "Adoration"....H.C. Miller AS CLEAN-UP DAYS HERE LOU H A [ iS Andante, "The Old Church Or~ 50TH ANN!WR R ' gan'. ................... W. P. Chambers 4-11 achiev¢.~nen~ days will bc The Band observed in Tuscola county at the At the council meeting Monday AI iED 81RGUITJUDE"Soft Shadows Falling"..Flemming following places next week: U RISE [ OLO Y evening, the trustees set aside May i FV FLli AL [ HURI H Boys' Glee Club Mayville , Monday evening, Apr. 14 and 15 as clean-up days in Cass , ,, "March Romaine". .............F. Beyer 23, at high school. T City. Trucks will be furnished by Serenade, "The Twilight Hour" Delegates Coming Here from Millington, Tuesday afternoon the village to cart away tin cans Lapeer Attorney Fills Vacan- ..........................Francis A. Myers L. D. Randall Speaks on Ag- ~Large Numbers Attended the Apr. 24, at M. E. church. t and other rubbish which are ,to be cy Caused bY Death of The Band Fifty Parishes in Thumb Akron, Tuesday evening, April ricultural Experiment placed at a convenient spot for Banquet and Two Sunday "Go Where the Water Glideth" Judge Smith. on May 5. 2~, at community hall. Near Chesaning. loading. Ash hauling will not be ..............................................Wilson Caro, Wednesday afternoon, Apr. done b:~ the village trucks. Services. Girls' Glee Club 25, at high school auditorium. -

Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Marketing Unveiled

SUGAR-SWEETENED BEVERAGE MARKETING UNVEILED VOLUME 1 VOLUME 2 VOLUME 3 VOLUME 4 THE PRODUCT: A VARIED OFFERING TO RESPOND TO A SEGMENTED MARKET A Multidimensional Approach to Reduce the Appeal of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages This report is a central component of the project entitled “A Multidimensional Approach to Reducing the Appeal of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages (SSBs)” launched by the Association pour la santé publique du Québec (ASPQ) and the Quebec Coalition on Weight-Related Problems (Weight Coalition) as part of the 2010 Innovation Strategy of the Public Health Agency of Canada on the theme of “Achieving Healthier Weights in Canada’s Communities”. This project is based on a major pan-Canadian partnership involving: • the Réseau du sport étudiant du Québec (RSEQ) • the Fédération du sport francophone de l’Alberta (FSFA) • the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC) • the Université Laval • the Public Health Association of BC (PHABC) • the Ontario Public Health Association (OPHA) The general aim of the project is to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages by changing attitudes toward their use and improving the food environment by making healthy choices easier. To do so, the project takes a three-pronged approach: • The preparation of this report, which offers an analysis of the Canadian sugar-sweetened beverage market and the associated marketing strategies aimed at young people (Weight Coalition/Université Laval); • The dissemination of tools, research, knowledge and campaigns on marketing sugar-sweetened beverages (PHABC/OPHA/Weight Coalition); • The adaptation in Francophone Alberta (FSFA/RSEQ) of the Quebec project Gobes-tu ça?, encouraging young people to develop a more critical view of advertising in this industry. -

Mark Alan Smith Formatted Dissertation

Copyright by Mark Alan Smith 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Mark Alan Smith Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: To Burn, To Howl, To Live Within the Truth: Underground Cultural Production in the U.S., U.S.S.R. and Czechoslovakia in the Post World War II Context and its Reception by Capitalist and Communist Power Structures. Committee: Thomas J. Garza, Supervisor Elizabeth Richmond-Garza Neil R. Nehring David D. Kornhaber To Burn, To Howl, To Live Within the Truth: Underground Cultural Production in the U.S., U.S.S.R. and Czechoslovakia in the Post World War II Context and its Reception by Capitalist and Communist Power Structures. by Mark Alan Smith. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2019 Dedication I would like to dedicate this work to Jesse Kelly-Landes, without whom it simply would not exist. I cannot thank you enough for your continued love and support. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Dr. Thomas J. Garza for all of his assistance, academically and otherwise. Additionally, I would like to thank the members of my dissertation committee, Dr. Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, Dr. Neil R. Nehring, and Dr. David D. Kornhaber for their invaluable assistance in this endeavor. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge the vital support of Dr. Veronika Tuckerová and Dr. Vladislav Beronja in contributing to the defense of my prospectus. -

4920 10 Cc D22-01 2Pac D43-01 50 Cent 4877 Abba 4574 Abba

ALDEBARAN KARAOKE Catálogo de Músicas - Por ordem de INTÉRPRETE Código INTÉRPRETE MÚSICA TRECHO DA MÚSICA 4920 10 CC I´M NOT IN LOVE I´m not in love so don´t forget it 19807 10000 MANIACS MORE THAN THIS I could feel at the time there was no way of D22-01 2PAC DEAR MAMA You are appreciated. When I was young 9033 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU A hundred days had made me older 2578 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN Starry night bring me down 9072 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP Twenty-five years and my life is still D36-01 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA I drove by all the places we used to hang out D36-02 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER HEARTBREAK GIRL You called me up, it´s like a broken record D36-03 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER JET BLACK HEART Everybody´s got their demons even wide D36-04 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT Simmer down, simmer down, they say we D43-01 50 CENT IN DA CLUB Go, go, go, go, shawty, it´s your birthday D54-01 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS I RAN I walk along the avenue, I never thought I´d D35-40 A TASTE OF HONEY BOOGIE OOGIE OOGIE If you´re thinkin´ you´re too cool to boogie D22-02 A TASTE OF HONEY SUKIYAKI It´s all because of you, I´m feeling 4970 A TEENS SUPER TROUPER Super trouper beams are gonna blind me 4877 ABBA CHIQUITITA Chiquitita tell me what´s wrong 4574 ABBA DANCING QUEEN Yeah! You can dance you can jive 19333 ABBA FERNANDO Can you hear the drums Fernando D17-01 ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME Half past twelve and I´m watching the late show D17-02 ABBA HAPPY NEW YEAR No more champagne and the fireworks 9116 ABBA I HAVE A DREAM I have a dream a song to sing… -

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst THE COMPLETE POETRY OF JAMES HEARST Edited by Scott Cawelti Foreword by Nancy Price university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright ᭧ 2001 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Sara T. Sauers http://www.uiowa.edu/ϳuipress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Northern Iowa, Dr. and Mrs. James McCutcheon, Norman Swanson, and the family of Dr. Robert J. Ward. Permission to print James Hearst’s poetry has been granted by the University of Northern Iowa Foundation, which owns the copyrights to Hearst’s work. Art on page iii by Gary Kelley Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearst, James, 1900–1983. [Poems] The complete poetry of James Hearst / edited by Scott Cawelti; foreword by Nancy Price. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-87745-756-5 (cloth), isbn 0-87745-757-3 (pbk.) I. Cawelti, G. Scott. II. Title. ps3515.e146 a17 2001 811Ј.52—dc21 00-066997 01 02 03 04 05 c 54321 01 02 03 04 05 p 54321 CONTENTS An Introduction to James Hearst by Nancy Price xxix Editor’s Preface xxxiii A journeyman takes what the journey will bring. -

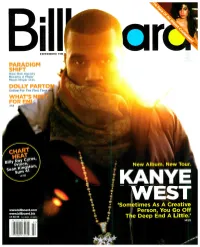

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE . -

Triller Network Acquires Verzuz: Exclusive

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 9, 2021 Page 1 of 25 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Triller Network Acquires Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience impressions, up 16%). Top Country• Verzuz Albums Founders chart dated April 18. In its first week (endingVerzuz: April 9), it Exclusive earnedSwizz 46,000 Beatz equivalent & album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingTimbaland to Nielsen Talk Music/MRC Data. andBY total GAIL Country MITCHELL Airplay No. 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideTriller Partnership: marks Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart‘This and fourthPuts a top Light 10. It followsVerzuz, freshman the LPpopular livestream music platform creat- in music todayYoung’s than Verzuz,” first of six said chart Bobby entries, Sarnevesht “Sleep With,- MontevalloBack on, which Creatives’ arrived at theed summit by Swizz in No Beatz- and Timbaland, has been acquired executive chairmanout You,” andreached co-owner No. 2 in of December Triller, in 2016. an- He vember 2014 and reigned for nineby weeks. Triller To Network, date, parent company of the Triller app. -

Voices De La Luna a Quarterly Poetry & Arts Magazine 15 August 2016

Voices de la Luna A Quarterly Poetry & Arts Magazine 15 August 2016 Volume 8, Number 4 www.voicesdelaluna.org “Phineas Talbot” by Brian Kenneth Swain Questions for Donna Dobberfuhl “Nocturne for Bellsong and Train Horns” by Bryce Milligan “Honoring Joy Harjo” by Abbie Massey Cotrell Table of Contents Rio San Pedro, Peter Holland 39 Voices de la Luna, Volume 8, Number 4 O. Henry Breathes Here, Carol Siskovic 39 Editor’s Note, James R. Adair 3 San Pedro Creek, Lea Lopez Fagin 39 Cover Page Art, Adam Green 4 International Poems Featured Poet Manchmal, Hejo Müller (Sometimes, trans. James High Country Caravan – Nocturne for Bellsong and Train Brandenburg) 19 Horns – The Watch – There Is No Cure for Desire, America! Tear Up This Bloody Amendment, Bryce Milligan 5 ( ), Majid Naficy 20 Advent’s End, Bryce Milligan 23 τί ἐστιν ἡ ἀγάπη; 1 Corinthians 13:4-7 (What Is Love? trans. James R. Adair) 20 Featured Interview Questions for Donna Dobberfuhl, Lauren Walthour 6 Stone in the Stream/Roca en el Río Six Brown Pelicans, Toni Heringer Falls 21 Collaboration in Literature & the Arts On the Edge of Town, Janice Rebecca Campbell 21 Creative Writing Reading Series 8 If I Had Attended, d. ellis phelps 21 How Many Painters Does It Take to Change a Nation, d. ellis UTSA Featured Poet phelps 21 Scales on the Harp, Alexis Haight 9 Editors’ Poems Book Reviews Genesis II, Mo H Saidi 22 The Train to Crystal City (Jan Jarboe Russell), Carol CalGarSi, Joan Strauch Seifert 22 Coffee Reposa 10 E. B. White Remembered, Carol Coffee Reposa 23 The High Mountains of Portugal (Yann Martel), James R. -

Paul Mccartney Pure Mp3, Flac, Wma

Paul McCartney Pure mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: Pure Country: France MP3 version RAR size: 1152 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1167 mb WMA version RAR size: 1653 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 207 Other Formats: AU WMA AC3 VQF AHX RA FLAC Tracklist 1-1 Maybe I'm Amazed 1-2 Heart Of The Country 1-3 Jet 1-4 Warm And Beautiful 1-5 Listen To What The Man Said 1-6 Dear Boy 1-7 Silly Love Songs 1-8 The Song We Were Singing 1-9 Uncle Albert 1-10 Another Day 1-11 Sing The Changes 1-12 Jenny Wren 1-13 Save Us 1-14 Mrs Vanderbilt 1-15 Mull Of Kintyre 1-16 Let Em In 1-17 Let Me Roll It 1-18 Nineteen Hundred And Eighty Five 1-19 Ebony And Ivory 2-1 Band On The Run 2-2 Arrow Through Me 2-3 My Love 2-4 Live And Let Die 2-5 Too Much Rain 2-6 Goodnight Tonight 2-7 Say Say Say 2-8 The World Tonight 2-9 My Valentine 2-10 Pipes Of Peace 2-11 Dance Tonight 2-12 Here Today 2-13 Wanderlust 2-14 Great Day 2-15 Coming Up 2-16 No More Lonely 2-17 Only Mama Knows 2-18 With A Little Luck 2-19 Hope For The Future 2-20 Junk Notes Insert + 2 french promo cds in plastic pocket Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Paul Pure McCartney Concord Music UCCO-3062 UCCO-3062 Japan 2016 McCartney (2xCD, Comp, SHM) Group, MPL Paul Pure McCartney Concord Music 7238690 7238690 Thailand 2016 McCartney (2xCD, Comp) Group, MPL Pure McCartney Paul Concord Music none (67xFile, AAC, none US 2016 McCartney Group, MPL Comp, Dlx, 256) Paul Pure McCartney Concord Music HRM-38690-02 HRM-38690-02 Europe 2016 McCartney (2xCD, Comp) Group, MPL Pure McCartney Paul Concord Music UCCO-8003 (4xCD, Comp, Ltd, UCCO-8003 Japan 2016 McCartney Group, MPL RM, SHM) Related Music albums to Pure by Paul McCartney 1. -

EU Page 01 COVER.Indd

entertaining u newspaper JACKSONVILLE design issue Daryl Bunn exhibit at Jane Gray Gallery | 48 Hour Film Project | Suicide Notes: new record store | Matthew’s Fine Dining free weekly guide to entertainment and more | august 9-15, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 august 9-15, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents Cover Photo by Rachel Best Henley - Home of Daryl Bunn feature Design Nation ................................................................................................. PAGES 16-23 Daryl Bunn (interview) ............................................................................. PAGES 16-17 Urban Architectural Design ...............................................................................PAGE 18 Personal Design ....................................................................................... PAGES 18-21 Interior Design .................................................................................................PAGE 19 Landscape Design ...........................................................................................PAGE 20 Tattoo Design ...................................................................................................PAGE 21 Event Design ............................................................................................ PAGES 22-23 Music Design .................................................................................................PAGES 23 movies Movies in Theaters this Week ...........................................................................