The Spotted Barbtail (Premnoplex Brunnescens )

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systematic Relationships and Biogeography of the Tracheophone Suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes)

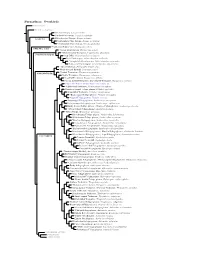

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 499–512 www.academicpress.com Systematic relationships and biogeography of the tracheophone suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes) Martin Irestedt,a,b,* Jon Fjeldsaa,c Ulf S. Johansson,a,b and Per G.P. Ericsona a Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Zoology, University of Stockholm, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden c Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Received 29 August 2001; received in revised form 17 January 2002 Abstract Based on their highly specialized ‘‘tracheophone’’ syrinx, the avian families Furnariidae (ovenbirds), Dendrocolaptidae (woodcreepers), Formicariidae (ground antbirds), Thamnophilidae (typical antbirds), Rhinocryptidae (tapaculos), and Conop- ophagidae (gnateaters) have long been recognized to constitute a monophyletic group of suboscine passerines. However, the monophyly of these families have been contested and their interrelationships are poorly understood, and this constrains the pos- sibilities for interpreting adaptive tendencies in this very diverse group. In this study we present a higher-level phylogeny and classification for the tracheophone birds based on phylogenetic analyses of sequence data obtained from 32 ingroup taxa. Both mitochondrial (cytochrome b) and nuclear genes (c-myc, RAG-1, and myoglobin) have been sequenced, and more than 3000 bp were subjected to parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses. The phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial and nuclear genes were compared and found to be very similar. The results from the analysis of the combined dataset (all genes, but with transitions at third codon positions in the cytochrome b excluded) partly corroborate previous phylogenetic hypotheses, but several novel arrangements were also suggested. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Distrito Regional De Manejo Integrado Cuervos Plan De

DISTRITO REGIONAL DE MANEJO INTEGRADO CUERVOS PLAN DE MANEJO Convenio Marco 423-2016, Acta de ejecución CT-2016-001532-10 - Cornare No 564-2017 Suscrito entre Cornare y EPM “Continuidad del convenio interadministrativo 423-2016 acta de ejecución CT-2016-001532-10 suscrito entre Cornare y EPM para la implementación de proyectos de conservación ambiental y uso sostenible de los recursos naturales en el Oriente antioqueño” PRESENTADO POR: GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD CORNARE EL Santuario – Antioquia 2018 REALIZACIÓN Corporación Autónoma Regional de las Cuencas de los Ríos Negro y Nare – Cornare GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD COORDINADORA DE GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD ELSA MARIA ACEVEDO CIFUENTES Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad SUPERVISOR DAVID ECHEVERRI LÓPEZ Biólogo (E), Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad SUPERVISOR EPM YULIE ANDREA JÍMENEZ GUZMAN Ingeniera Forestal, Epm EQUIPO PROFESIONAL GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD LUZ ÁNGELA RIVERO HENAO Ingeniera Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad EDUARDO ANTONIO RIOS PINEDO Ingeniero Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad DANIEL MARTÍNEZ CASTAÑO Biólogo, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad STIVEN BARRIENTOS GÓMEZ Ingeniero Ambiental, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad NICOLAS RESTREPO ROMERO Ingeniero Ambiental, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad JULIETH VELASQUEZ AGUDELO Ingeniera Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad SANTIAGO OSORIO YEPES Ingeniero Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad TABLA DE CONTENIDO 1. INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................................... -

MS1001 Greeney

The nest of the Pearled Treerunner (Margarornis squamiger ) Artículo El nido del Subepalo Perlado (Margarornis squamiger) Harold F. Greeney1 & Rudy A. Gelis2 1Yanayacu Biological Station & Center for Creative Studies, Cosanga, Napo Province, Ecuador, c/o 721 Foch y Amazonas, Quito, Ecuador. [email protected] 2Pluma Verde Tours, Pasaje Manuel Garcia y 18 de Septiembre N20-28 Quito, Ecuador. Abstract Ornitología Colombiana Ornitología The Pearled Treerunner (Margarornis squamiger) is a small ovenbird (Furnariidae) inhabiting the upper strata of Neotropical montane forests. Little is known of its breeding habits despite its wide distribution and abundance within appropriate habitat. The genus Margarornis is considered closely related to Premnoplex barbtails, but details of nest architecture supporting this relationship are unavailable. Here we provide the first detailed description of nest architecture for the Pearled Treerunner from a nest encountered in northwest Ecuador. The nest was a tightly woven ball of moss and rootlets, similar in shape to that of the Spotted Barbtail (Premnoplex brunnescens) and presumably built in a similar manner. Nest architecture and nes- tling behavior support a close relationship between Margarornis and Premnoplex. Key words: barbtail, Ecuador, Furnariidae, Margarornis squamiger, nest architecture. Resumen El Subepalo Perlado (Margarornis squamiger) es un furnárido pequeño que habita el dosel de los bosques de montaña neo- tropicales. La reproducción de esta especie es poco conocida, a pesar de su amplia distribución y de ser común en el hábi- tat adecuado. El género Margarornis se considera cercanamente emparentado con los subepalos del género Premnoplex, pero no se conocen detalles de la arquitectura del nido que sustenten esta relación. -

Evolution of the Ovenbird-Woodcreeper Assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Б/ Major Shifts in Nest Architecture and Adaptive Radiatio

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 37: 260Á/272, 2006 Evolution of the ovenbird-woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) / major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation Á Martin Irestedt, Jon Fjeldsa˚ and Per G. P. Ericson Irestedt, M., Fjeldsa˚, J. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2006. Evolution of the ovenbird- woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Á/ major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation. Á/ J. Avian Biol. 37: 260Á/272 The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) form an extraordinary morphologically and ecologically diverse passerine radiation, which includes many examples of species that are superficially similar to other passerine birds as a resulting from their adaptations to similar lifestyles. The ovenbirds further exhibits a truly remarkable variation in nest types, arguably approaching that found in the entire passerine clade. Herein we present a genus-level phylogeny of ovenbirds based on both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA including a more complete taxon sampling than in previous molecular studies of the group. The phylogenetic results are in good agreement with earlier molecular studies of ovenbirds, and supports the suggestion that Geositta and Sclerurus form the sister clade to both core-ovenbirds and woodcreepers. Within the core-ovenbirds several relationships that are incongruent with traditional classifications are suggested. Among other things, the philydorine ovenbirds are found to be non-monophyletic. The mapping of principal nesting strategies onto the molecular phylogeny suggests cavity nesting to be plesiomorphic within the ovenbirdÁ/woodcreeper radiation. It is also suggested that the shift from cavity nesting to building vegetative nests is likely to have happened at least three times during the evolution of the group. -

Inventario De Flora Y Fauna En El CBIMA (12.6

ii CRÉDITOS Comité Directivo José Vicente Troya Rodríguez Representante Residente del PNUD en Costa Rica Kryssia Brade Representante Residente Adjunta del PNUD en Costa Rica Coordinado por Miriam Miranda Quirós Coordinadora del proyecto Paisajes Productivos-PNUD Consultores que trabajaron en la realización del estudio José Esteban Jiménez, estudio de plantas vasculares Federico Oviedo Brenes, estudio de plantas vasculares Fabián Araya Yannarella, estudio de hongos Víctor J. Acosta-Chaves, estudios de aves, de anfibios y de reptiles Susana Gutiérrez Acuña, estudio de mamíferos Revisado por el comité editorial PNUD Rafaella Sánchez Ingrid Hernández Jose Daniel Estrada Diseño y diagramación Marvin Rojas San José, Costa Rica, 2019 iii RESUMEN EJECUTIVO El conocimiento sobre la diversidad 84 especies esperadas, 21 especies de biológica que habita los ecosistemas anfibios y 84 especies de reptiles. naturales, tanto boscosos como no boscosos, así como en áreas rurales y La diversidad acá presentada, con urbanas, es la línea base fundamental excepción de los hongos, es entre 100 y para establecer un manejo y una gestión 250% mayor respecto al estudio similar adecuadas sobre la protección, efectuado en el 2001 (FUNDENA 2001). conservación y uso sostenible de los La cantidad de especies sensibles es recursos naturales. En el Corredor baja para cada grupo de organismos Biológico Interurbano Maria Aguilar se respecto al total. El CBIMA posee una encontró un total de 765 especies de gran cantidad de especies de plantas plantas vasculares, (74.9% son nativas nativas con alto potencial para restaurar de Costa Rica y crecen naturalmente en espacios físicos degradados y para el CBIMA, un 3.5% son nativas de Costa utilizar como ornamentales. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae)

The Auk 116(4):891-911, 1999 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF NEOTROPICAL OVENBIRDS (FURNARIIDAE) KRZYSZTOF ZYSKOWSKI • AND RICHARD O. PRUM NaturalHistory Museum and Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Wereviewed the tremendousarchitectural diversity of ovenbird(Furnari- idae) nestsbased on literature,museum collections, and new field observations.With few exceptions,furnariids exhibited low intraspecificvariation for the nestcharacters hypothe- sized,with the majorityof variationbeing hierarchicallydistributed among taxa. We hy- pothesizednest homologies for 168species in 41 genera(ca. 70% of all speciesand genera) and codedthem as 24 derivedcharacters. Forty-eight most-parsimonious trees (41 steps,CI = 0.98, RC = 0.97) resultedfrom a parsimonyanalysis of the equallyweighted characters using PAUP,with the Dendrocolaptidaeand Formicarioideaas successiveoutgroups. The strict-consensustopology based on thesetrees contained 15 cladesrepresenting both tra- ditionaltaxa and novelphylogenetic groupings. Comparisons with the outgroupsdemon- stratethat cavitynesting is plesiomorphicto the furnariids.In the two lineageswhere the primitivecavity nest has been lost, novel nest structures have evolved to enclosethe nest contents:the clayoven of Furnariusand the domedvegetative nest of the synallaxineclade. Althoughour phylogenetichypothesis should be consideredas a heuristicprediction to be testedsubsequently by additionalcharacter evidence, this first cladisticanalysis -

Furnariinae Species Tree, Part 1

Furnariinae: Ovenbirds Sclerurinae Dendrocolaptinae Streaked Xenops, Xenops rutilans Slender-billed Xenops, Xenops tenuirostris Xenops minutus XENOPINI White-throated Xenops, Northwestern Plain Xenops, Xenops mexicanus !Southeastern Plain Xenops, Xenops genibarbus !Point-tailed Palmcreeper, Berlepschia rikeri BERLEPSCHIINI ! Rufous-tailed Xenops, Microxenops milleri !White-throated Treerunner, Pygarrhichas albogularis PYGARRHICHADINI Crag Chilia, Ochetorhynchus melanurus Rock Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus andaecola !Straight-billed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus ruficaudus Band-tailed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus phoenicurus !Spotted Barbtail, Premnoplex brunnescens White-throated Barbtail, Premnoplex tatei !Pearled Treerunner, Margarornis squamiger MARGARORNINI Ruddy Treerunner, Margarornis rubiginosus Beautiful Treerunner, Margarornis bellulus Fulvous-dotted Treerunner / Star-chested Treerunner, Margarornis stellatus Cryptic Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti !Pale-browed Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes leucophrus Cinnamon-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor pyrrhodes Sharp-billed Treehunter, Philydor contaminatus !Black-capped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor atricapillus Alagoas Foliage-gleaner, Philydor novaesi Slaty-winged Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscipennis Rufous-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops erythrocercus Dusky-cheeked Foliage-gleaner / Bamboo Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops dorsalis !White-collared Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscus !Great Xenops, Megaxenops parnaguae Ochre-breasted Foliage-gleaner, Anabacerthia lichtensteini White-browed -

Behavior and Phylogenetic Position of Premnoplex Barbtails (Furnariidae)

The Condor 109:399–407 # The Cooper Ornithological Society 2007 BEHAVIOR AND PHYLOGENETIC POSITION OF PREMNOPLEX BARBTAILS (FURNARIIDAE) JUAN IGNACIO ARETA1,2,3 1CICyTTP-CONICET, Materi y Espan˜a, 3105, Diamante, Entre Rı´os, Argentina 2Grupo FALCO, El Coronillo, Reserva Natural Punta Lara, 1915, Ensenada, Buenos Aires, Argentina Abstract. The Margarornis assemblage includes four genera: Margarornis, Premno- plex, Premnornis, and Roraimia, all thought to be closely related. Differences in vocalizations and habitat use between Premnoplex brunnescens (Spotted Barbtail) and P. tatei (White-throated Barbtail) are consistent with their full species status. In light of the weak anatomical (hindlimb musculature) evidence supporting the inclusion of Premnornis in the Margarornis assemblage, the convergence-prone nature of characters associated with climbing habits, and the differences in their nests and foraging behavior, I propose that Premnornis is not a member of the Margarornis assemblage and that Premnoplex is closely related only to Margarornis. These results are supported by recent molecular phylogenetic analyses. Although Roraimia differs in plumage, tail shape, and song from other members of the Margarornis assemblage, it must be provisionally included in the assemblage until evidence clarifies its phylogenetic position. Key words: barbtails, behavior, convergence, morphology, nest, Premnoplex, Premnornis. Comportamiento y Posicio´n Filogene´tica de los Premnoplex (Furnariidae) Resumen. El ensamble Margarornis incluye cuatro ge´neros: -

Seasonality and Elevational Migration in an Andean Bird Community

SEASONALITY AND ELEVATIONAL MIGRATION IN AN ANDEAN BIRD COMMUNITY _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CHRISTOPHER L. MERKORD Dr. John Faaborg, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2010 © Copyright by Christopher L. Merkord 2010 All Rights reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled ELEVATIONAL MIGRATION OF BIRDS ON THE EASTERN SLOPE OF THE ANDES IN SOUTHEASTERN PERU presented by Christopher L. Merkord, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor John Faaborg Professor James Carrel Professor Raymond Semlitsch Professor Frank Thompson Professor Miles Silman For mom and dad… ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was completed with the mentoring, guidance, support, advice, enthusiasm, dedication, and collaboration of a great many people. Each chapter has its own acknowledgments, but here I want to mention the people who helped bring this dissertation together as a whole. First and foremost my parents, for raising me outdoors, hosting an endless stream of squirrels, snakes, lizards, turtles, fish, birds, and other pets, passing on their 20-year old Spacemaster spotting scope, showing me every natural ecosystem within a three day drive, taking me on my first trip to the tropics, putting up with all manner of trouble I’ve gotten myself into while pursuing my dreams, and for offering my their constant love and support. Tony Ortiz, for helping me while away the hours, and for sharing with me his sense of humor. -

Field Guides Tour Report Mountains of Manu, Peru I 2019

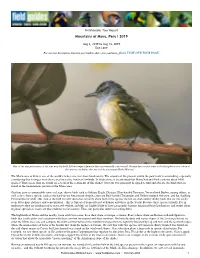

Field Guides Tour Report Mountains of Manu, Peru I 2019 Aug 2, 2019 to Aug 13, 2019 Dan Lane For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. One of the star performers of the tour was this bold Yellow-rumped Antwren that was unusually extroverted! We may have gotten some of the best photos ever taken of this species, including this fine one by participant Becky Hansen! The Manu area of Peru is one of the world's richest sites for sheer biodiversity. The amount of life present within the park itself is astonishing, especially considering that it ranges from above treeline to the Amazon lowlands. In birds alone, it is estimated that Manu National Park contains about 1000 species! That's more than are found on several of the continents of this planet! Our tour was primarily designed to find and observe the birds that are found in the mountainous portion of the Manu area. Our tour gave us memorable views of large, showy birds such as Solitary Eagle, Hoatzin, Blue-banded Toucanet, Versicolored Barbet, among others, as well as less showy species such as the hard-to-see Amazonian Antpitta, the rare Buff-banded Tyrannulet and Yellow-rumped Antwren, and the skulking Peruvian Recurvebill. One look at the bird list will show that certainly about half of the species therein are drab and/or skulky birds that are not easily seen, but require patience and concentration... this is typical of tropical forest avifaunas anywhere in the world. Because these species usually live in understory, they are predisposed to not travel widely, and thus are highly likely to have geographic barriers fragment their distributions and render them regional specialists; many are thus endemic to the country. -

The Birds of Abra Patricia and the Upper Río Mayo, San Martín, North

T h e birds of Ab r a Patricia and the upper río Mayo, San Martín, north Peru Jon Hornbuckle Cotinga 12 (1999): 11– 28 En 1998 se llevó a cabo un inventario ornitológico en un bosque al este de Abra Patricia, Departamento San Martín, norte de Perú, en el cual se registraron 317 especies de aves. Junto con los registros previamente publicados y observaciones recientes realizadas por visitantes al área, el número de especies asciende a por lo menos 420. De éstas, 23 están clasificadas como amenazadas globalmente3, incluyendo Xenoglaux loweryi y Grallaricula ochraceifrons, ambas prácticamente desconocidas. Además, se registraron siete especies de distribución restringida. A pesar de que el ‘Bosque de Protección del Alto Mayo’ protege teóricamente 182 000 ha, la tala del bosque es una actividad frecuente y al parecer no existen medidas reales de control. En la actualidad se están realizando esfuerzos para conservar esta importante área. Introduction ochraceifrons10,15. However, ornithological surveys of In northern Peru, the forest east of the Abra Patricia this area have been confined to three Louisiana pass, dpto. San Martin (see Appendix 3 for State University Museum of Zoology (LSUMZ) coordinates) is of particular interest to expeditions, totalling six weeks: in 1976, 1977 and ornithologists as it is the type-locality for the near- 19835,15,18. Since that period the region has been too mythical Long-whiskered Owlet Xenoglaux loweryi dangerous to visit, until the recent cessation of and Ochre-fronted Antpitta Grallaricula guerilla activities. 11 Cotinga 12 The birds of Abra Patricia and the upper río Mayo, San M artín, north Peru The area is located at the northern end of the The habitat at the LSUMZ study sites has been Cordillera Oriental, the easternmost range of the described in some detail5,15,17 but can be summarised north Peruvian Andes, sloping eastward to the Rio at the lower elevations as subtropical forest of tall Mayo.