Behavior and Phylogenetic Position of Premnoplex Barbtails (Furnariidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Systematic Relationships and Biogeography of the Tracheophone Suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 499–512 www.academicpress.com Systematic relationships and biogeography of the tracheophone suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes) Martin Irestedt,a,b,* Jon Fjeldsaa,c Ulf S. Johansson,a,b and Per G.P. Ericsona a Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Zoology, University of Stockholm, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden c Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Received 29 August 2001; received in revised form 17 January 2002 Abstract Based on their highly specialized ‘‘tracheophone’’ syrinx, the avian families Furnariidae (ovenbirds), Dendrocolaptidae (woodcreepers), Formicariidae (ground antbirds), Thamnophilidae (typical antbirds), Rhinocryptidae (tapaculos), and Conop- ophagidae (gnateaters) have long been recognized to constitute a monophyletic group of suboscine passerines. However, the monophyly of these families have been contested and their interrelationships are poorly understood, and this constrains the pos- sibilities for interpreting adaptive tendencies in this very diverse group. In this study we present a higher-level phylogeny and classification for the tracheophone birds based on phylogenetic analyses of sequence data obtained from 32 ingroup taxa. Both mitochondrial (cytochrome b) and nuclear genes (c-myc, RAG-1, and myoglobin) have been sequenced, and more than 3000 bp were subjected to parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses. The phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial and nuclear genes were compared and found to be very similar. The results from the analysis of the combined dataset (all genes, but with transitions at third codon positions in the cytochrome b excluded) partly corroborate previous phylogenetic hypotheses, but several novel arrangements were also suggested. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta. -

Costa Rica: the Introtour | July 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour Costa Rica: The Introtour July 15 – 25, 2017 Tour Leader: Scott Olmstead INTRODUCTION This year’s July departure of the Costa Rica Introtour had great luck with many of the most spectacular, emblematic birds of Central America like Resplendent Quetzal (photo right), Three-wattled Bellbird, Great Green and Scarlet Macaws, and Keel-billed Toucan, as well as some excellent rarities like Black Hawk- Eagle, Ochraceous Pewee and Azure-hooded Jay. We enjoyed great weather for birding, with almost no morning rain throughout the trip, and just a few delightful afternoon and evening showers. Comfortable accommodations, iconic landscapes, abundant, delicious meals, and our charismatic driver Luís enhanced our time in the field. Our group, made up of a mix of first- timers to the tropics and more seasoned tropical birders, got along wonderfully, with some spying their first-ever toucans, motmots, puffbirds, etc. on this trip, and others ticking off regional endemics and hard-to-get species. We were fortunate to have several high-quality mammal sightings, including three monkey species, Derby’s Wooly Opossum, Northern Tamandua, and Tayra. Then there were many www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 superb reptiles and amphibians, among them Emerald Basilisk, Helmeted Iguana, Green-and- black and Strawberry Poison Frogs, and Red-eyed Leaf Frog. And on a daily basis we saw many other fantastic and odd tropical treasures like glorious Blue Morpho butterflies, enormous tree ferns, and giant stick insects! TOP FIVE BIRDS OF THE TOUR (as voted by the group) 1. -

Bird Monitoring Study Data Report Jan 2013 – Dec 2016

Bird Monitoring Study Data Report Jan 2013 – Dec 2016 Jennifer Powell Cloudbridge Nature Reserve October 2017 Photos: Nathan Marcy Common Chlorospingus Slate-throated Redstart (Chlorospingus flavopectus) (Myioborus miniatus) CONTENTS Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Tables .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Figures................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Project Background ................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Project Goals ................................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Locations ..................................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Current locations ............................................................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Historic locations ..........................................................................................................................................10 -

Distrito Regional De Manejo Integrado Cuervos Plan De

DISTRITO REGIONAL DE MANEJO INTEGRADO CUERVOS PLAN DE MANEJO Convenio Marco 423-2016, Acta de ejecución CT-2016-001532-10 - Cornare No 564-2017 Suscrito entre Cornare y EPM “Continuidad del convenio interadministrativo 423-2016 acta de ejecución CT-2016-001532-10 suscrito entre Cornare y EPM para la implementación de proyectos de conservación ambiental y uso sostenible de los recursos naturales en el Oriente antioqueño” PRESENTADO POR: GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD CORNARE EL Santuario – Antioquia 2018 REALIZACIÓN Corporación Autónoma Regional de las Cuencas de los Ríos Negro y Nare – Cornare GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD COORDINADORA DE GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD ELSA MARIA ACEVEDO CIFUENTES Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad SUPERVISOR DAVID ECHEVERRI LÓPEZ Biólogo (E), Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad SUPERVISOR EPM YULIE ANDREA JÍMENEZ GUZMAN Ingeniera Forestal, Epm EQUIPO PROFESIONAL GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD LUZ ÁNGELA RIVERO HENAO Ingeniera Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad EDUARDO ANTONIO RIOS PINEDO Ingeniero Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad DANIEL MARTÍNEZ CASTAÑO Biólogo, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad STIVEN BARRIENTOS GÓMEZ Ingeniero Ambiental, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad NICOLAS RESTREPO ROMERO Ingeniero Ambiental, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad JULIETH VELASQUEZ AGUDELO Ingeniera Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad SANTIAGO OSORIO YEPES Ingeniero Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad TABLA DE CONTENIDO 1. INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................................... -

MS1001 Greeney

The nest of the Pearled Treerunner (Margarornis squamiger ) Artículo El nido del Subepalo Perlado (Margarornis squamiger) Harold F. Greeney1 & Rudy A. Gelis2 1Yanayacu Biological Station & Center for Creative Studies, Cosanga, Napo Province, Ecuador, c/o 721 Foch y Amazonas, Quito, Ecuador. [email protected] 2Pluma Verde Tours, Pasaje Manuel Garcia y 18 de Septiembre N20-28 Quito, Ecuador. Abstract Ornitología Colombiana Ornitología The Pearled Treerunner (Margarornis squamiger) is a small ovenbird (Furnariidae) inhabiting the upper strata of Neotropical montane forests. Little is known of its breeding habits despite its wide distribution and abundance within appropriate habitat. The genus Margarornis is considered closely related to Premnoplex barbtails, but details of nest architecture supporting this relationship are unavailable. Here we provide the first detailed description of nest architecture for the Pearled Treerunner from a nest encountered in northwest Ecuador. The nest was a tightly woven ball of moss and rootlets, similar in shape to that of the Spotted Barbtail (Premnoplex brunnescens) and presumably built in a similar manner. Nest architecture and nes- tling behavior support a close relationship between Margarornis and Premnoplex. Key words: barbtail, Ecuador, Furnariidae, Margarornis squamiger, nest architecture. Resumen El Subepalo Perlado (Margarornis squamiger) es un furnárido pequeño que habita el dosel de los bosques de montaña neo- tropicales. La reproducción de esta especie es poco conocida, a pesar de su amplia distribución y de ser común en el hábi- tat adecuado. El género Margarornis se considera cercanamente emparentado con los subepalos del género Premnoplex, pero no se conocen detalles de la arquitectura del nido que sustenten esta relación. -

Evolution of the Ovenbird-Woodcreeper Assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Б/ Major Shifts in Nest Architecture and Adaptive Radiatio

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 37: 260Á/272, 2006 Evolution of the ovenbird-woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) / major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation Á Martin Irestedt, Jon Fjeldsa˚ and Per G. P. Ericson Irestedt, M., Fjeldsa˚, J. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2006. Evolution of the ovenbird- woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Á/ major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation. Á/ J. Avian Biol. 37: 260Á/272 The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) form an extraordinary morphologically and ecologically diverse passerine radiation, which includes many examples of species that are superficially similar to other passerine birds as a resulting from their adaptations to similar lifestyles. The ovenbirds further exhibits a truly remarkable variation in nest types, arguably approaching that found in the entire passerine clade. Herein we present a genus-level phylogeny of ovenbirds based on both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA including a more complete taxon sampling than in previous molecular studies of the group. The phylogenetic results are in good agreement with earlier molecular studies of ovenbirds, and supports the suggestion that Geositta and Sclerurus form the sister clade to both core-ovenbirds and woodcreepers. Within the core-ovenbirds several relationships that are incongruent with traditional classifications are suggested. Among other things, the philydorine ovenbirds are found to be non-monophyletic. The mapping of principal nesting strategies onto the molecular phylogeny suggests cavity nesting to be plesiomorphic within the ovenbirdÁ/woodcreeper radiation. It is also suggested that the shift from cavity nesting to building vegetative nests is likely to have happened at least three times during the evolution of the group. -

Inventario De Flora Y Fauna En El CBIMA (12.6

ii CRÉDITOS Comité Directivo José Vicente Troya Rodríguez Representante Residente del PNUD en Costa Rica Kryssia Brade Representante Residente Adjunta del PNUD en Costa Rica Coordinado por Miriam Miranda Quirós Coordinadora del proyecto Paisajes Productivos-PNUD Consultores que trabajaron en la realización del estudio José Esteban Jiménez, estudio de plantas vasculares Federico Oviedo Brenes, estudio de plantas vasculares Fabián Araya Yannarella, estudio de hongos Víctor J. Acosta-Chaves, estudios de aves, de anfibios y de reptiles Susana Gutiérrez Acuña, estudio de mamíferos Revisado por el comité editorial PNUD Rafaella Sánchez Ingrid Hernández Jose Daniel Estrada Diseño y diagramación Marvin Rojas San José, Costa Rica, 2019 iii RESUMEN EJECUTIVO El conocimiento sobre la diversidad 84 especies esperadas, 21 especies de biológica que habita los ecosistemas anfibios y 84 especies de reptiles. naturales, tanto boscosos como no boscosos, así como en áreas rurales y La diversidad acá presentada, con urbanas, es la línea base fundamental excepción de los hongos, es entre 100 y para establecer un manejo y una gestión 250% mayor respecto al estudio similar adecuadas sobre la protección, efectuado en el 2001 (FUNDENA 2001). conservación y uso sostenible de los La cantidad de especies sensibles es recursos naturales. En el Corredor baja para cada grupo de organismos Biológico Interurbano Maria Aguilar se respecto al total. El CBIMA posee una encontró un total de 765 especies de gran cantidad de especies de plantas plantas vasculares, (74.9% son nativas nativas con alto potencial para restaurar de Costa Rica y crecen naturalmente en espacios físicos degradados y para el CBIMA, un 3.5% son nativas de Costa utilizar como ornamentales. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae)

The Auk 116(4):891-911, 1999 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF NEOTROPICAL OVENBIRDS (FURNARIIDAE) KRZYSZTOF ZYSKOWSKI • AND RICHARD O. PRUM NaturalHistory Museum and Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Wereviewed the tremendousarchitectural diversity of ovenbird(Furnari- idae) nestsbased on literature,museum collections, and new field observations.With few exceptions,furnariids exhibited low intraspecificvariation for the nestcharacters hypothe- sized,with the majorityof variationbeing hierarchicallydistributed among taxa. We hy- pothesizednest homologies for 168species in 41 genera(ca. 70% of all speciesand genera) and codedthem as 24 derivedcharacters. Forty-eight most-parsimonious trees (41 steps,CI = 0.98, RC = 0.97) resultedfrom a parsimonyanalysis of the equallyweighted characters using PAUP,with the Dendrocolaptidaeand Formicarioideaas successiveoutgroups. The strict-consensustopology based on thesetrees contained 15 cladesrepresenting both tra- ditionaltaxa and novelphylogenetic groupings. Comparisons with the outgroupsdemon- stratethat cavitynesting is plesiomorphicto the furnariids.In the two lineageswhere the primitivecavity nest has been lost, novel nest structures have evolved to enclosethe nest contents:the clayoven of Furnariusand the domedvegetative nest of the synallaxineclade. Althoughour phylogenetichypothesis should be consideredas a heuristicprediction to be testedsubsequently by additionalcharacter evidence, this first cladisticanalysis -

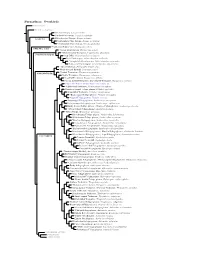

Furnariinae Species Tree, Part 1

Furnariinae: Ovenbirds Sclerurinae Dendrocolaptinae Streaked Xenops, Xenops rutilans Slender-billed Xenops, Xenops tenuirostris Xenops minutus XENOPINI White-throated Xenops, Northwestern Plain Xenops, Xenops mexicanus !Southeastern Plain Xenops, Xenops genibarbus !Point-tailed Palmcreeper, Berlepschia rikeri BERLEPSCHIINI ! Rufous-tailed Xenops, Microxenops milleri !White-throated Treerunner, Pygarrhichas albogularis PYGARRHICHADINI Crag Chilia, Ochetorhynchus melanurus Rock Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus andaecola !Straight-billed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus ruficaudus Band-tailed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus phoenicurus !Spotted Barbtail, Premnoplex brunnescens White-throated Barbtail, Premnoplex tatei !Pearled Treerunner, Margarornis squamiger MARGARORNINI Ruddy Treerunner, Margarornis rubiginosus Beautiful Treerunner, Margarornis bellulus Fulvous-dotted Treerunner / Star-chested Treerunner, Margarornis stellatus Cryptic Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti !Pale-browed Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes leucophrus Cinnamon-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor pyrrhodes Sharp-billed Treehunter, Philydor contaminatus !Black-capped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor atricapillus Alagoas Foliage-gleaner, Philydor novaesi Slaty-winged Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscipennis Rufous-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops erythrocercus Dusky-cheeked Foliage-gleaner / Bamboo Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops dorsalis !White-collared Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscus !Great Xenops, Megaxenops parnaguae Ochre-breasted Foliage-gleaner, Anabacerthia lichtensteini White-browed