Elevational Correlates of Speciation and Intraspecific Geographic Variation in Plumage in Andean Forest Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systematic Relationships and Biogeography of the Tracheophone Suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 499–512 www.academicpress.com Systematic relationships and biogeography of the tracheophone suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes) Martin Irestedt,a,b,* Jon Fjeldsaa,c Ulf S. Johansson,a,b and Per G.P. Ericsona a Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Zoology, University of Stockholm, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden c Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Received 29 August 2001; received in revised form 17 January 2002 Abstract Based on their highly specialized ‘‘tracheophone’’ syrinx, the avian families Furnariidae (ovenbirds), Dendrocolaptidae (woodcreepers), Formicariidae (ground antbirds), Thamnophilidae (typical antbirds), Rhinocryptidae (tapaculos), and Conop- ophagidae (gnateaters) have long been recognized to constitute a monophyletic group of suboscine passerines. However, the monophyly of these families have been contested and their interrelationships are poorly understood, and this constrains the pos- sibilities for interpreting adaptive tendencies in this very diverse group. In this study we present a higher-level phylogeny and classification for the tracheophone birds based on phylogenetic analyses of sequence data obtained from 32 ingroup taxa. Both mitochondrial (cytochrome b) and nuclear genes (c-myc, RAG-1, and myoglobin) have been sequenced, and more than 3000 bp were subjected to parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses. The phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial and nuclear genes were compared and found to be very similar. The results from the analysis of the combined dataset (all genes, but with transitions at third codon positions in the cytochrome b excluded) partly corroborate previous phylogenetic hypotheses, but several novel arrangements were also suggested. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

MS1001 Greeney

The nest of the Pearled Treerunner (Margarornis squamiger ) Artículo El nido del Subepalo Perlado (Margarornis squamiger) Harold F. Greeney1 & Rudy A. Gelis2 1Yanayacu Biological Station & Center for Creative Studies, Cosanga, Napo Province, Ecuador, c/o 721 Foch y Amazonas, Quito, Ecuador. [email protected] 2Pluma Verde Tours, Pasaje Manuel Garcia y 18 de Septiembre N20-28 Quito, Ecuador. Abstract Ornitología Colombiana Ornitología The Pearled Treerunner (Margarornis squamiger) is a small ovenbird (Furnariidae) inhabiting the upper strata of Neotropical montane forests. Little is known of its breeding habits despite its wide distribution and abundance within appropriate habitat. The genus Margarornis is considered closely related to Premnoplex barbtails, but details of nest architecture supporting this relationship are unavailable. Here we provide the first detailed description of nest architecture for the Pearled Treerunner from a nest encountered in northwest Ecuador. The nest was a tightly woven ball of moss and rootlets, similar in shape to that of the Spotted Barbtail (Premnoplex brunnescens) and presumably built in a similar manner. Nest architecture and nes- tling behavior support a close relationship between Margarornis and Premnoplex. Key words: barbtail, Ecuador, Furnariidae, Margarornis squamiger, nest architecture. Resumen El Subepalo Perlado (Margarornis squamiger) es un furnárido pequeño que habita el dosel de los bosques de montaña neo- tropicales. La reproducción de esta especie es poco conocida, a pesar de su amplia distribución y de ser común en el hábi- tat adecuado. El género Margarornis se considera cercanamente emparentado con los subepalos del género Premnoplex, pero no se conocen detalles de la arquitectura del nido que sustenten esta relación. -

Evolution of the Ovenbird-Woodcreeper Assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Б/ Major Shifts in Nest Architecture and Adaptive Radiatio

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 37: 260Á/272, 2006 Evolution of the ovenbird-woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) / major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation Á Martin Irestedt, Jon Fjeldsa˚ and Per G. P. Ericson Irestedt, M., Fjeldsa˚, J. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2006. Evolution of the ovenbird- woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Á/ major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation. Á/ J. Avian Biol. 37: 260Á/272 The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) form an extraordinary morphologically and ecologically diverse passerine radiation, which includes many examples of species that are superficially similar to other passerine birds as a resulting from their adaptations to similar lifestyles. The ovenbirds further exhibits a truly remarkable variation in nest types, arguably approaching that found in the entire passerine clade. Herein we present a genus-level phylogeny of ovenbirds based on both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA including a more complete taxon sampling than in previous molecular studies of the group. The phylogenetic results are in good agreement with earlier molecular studies of ovenbirds, and supports the suggestion that Geositta and Sclerurus form the sister clade to both core-ovenbirds and woodcreepers. Within the core-ovenbirds several relationships that are incongruent with traditional classifications are suggested. Among other things, the philydorine ovenbirds are found to be non-monophyletic. The mapping of principal nesting strategies onto the molecular phylogeny suggests cavity nesting to be plesiomorphic within the ovenbirdÁ/woodcreeper radiation. It is also suggested that the shift from cavity nesting to building vegetative nests is likely to have happened at least three times during the evolution of the group. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae)

The Auk 116(4):891-911, 1999 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF NEOTROPICAL OVENBIRDS (FURNARIIDAE) KRZYSZTOF ZYSKOWSKI • AND RICHARD O. PRUM NaturalHistory Museum and Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Wereviewed the tremendousarchitectural diversity of ovenbird(Furnari- idae) nestsbased on literature,museum collections, and new field observations.With few exceptions,furnariids exhibited low intraspecificvariation for the nestcharacters hypothe- sized,with the majorityof variationbeing hierarchicallydistributed among taxa. We hy- pothesizednest homologies for 168species in 41 genera(ca. 70% of all speciesand genera) and codedthem as 24 derivedcharacters. Forty-eight most-parsimonious trees (41 steps,CI = 0.98, RC = 0.97) resultedfrom a parsimonyanalysis of the equallyweighted characters using PAUP,with the Dendrocolaptidaeand Formicarioideaas successiveoutgroups. The strict-consensustopology based on thesetrees contained 15 cladesrepresenting both tra- ditionaltaxa and novelphylogenetic groupings. Comparisons with the outgroupsdemon- stratethat cavitynesting is plesiomorphicto the furnariids.In the two lineageswhere the primitivecavity nest has been lost, novel nest structures have evolved to enclosethe nest contents:the clayoven of Furnariusand the domedvegetative nest of the synallaxineclade. Althoughour phylogenetichypothesis should be consideredas a heuristicprediction to be testedsubsequently by additionalcharacter evidence, this first cladisticanalysis -

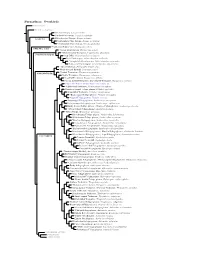

Furnariinae Species Tree, Part 1

Furnariinae: Ovenbirds Sclerurinae Dendrocolaptinae Streaked Xenops, Xenops rutilans Slender-billed Xenops, Xenops tenuirostris Xenops minutus XENOPINI White-throated Xenops, Northwestern Plain Xenops, Xenops mexicanus !Southeastern Plain Xenops, Xenops genibarbus !Point-tailed Palmcreeper, Berlepschia rikeri BERLEPSCHIINI ! Rufous-tailed Xenops, Microxenops milleri !White-throated Treerunner, Pygarrhichas albogularis PYGARRHICHADINI Crag Chilia, Ochetorhynchus melanurus Rock Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus andaecola !Straight-billed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus ruficaudus Band-tailed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus phoenicurus !Spotted Barbtail, Premnoplex brunnescens White-throated Barbtail, Premnoplex tatei !Pearled Treerunner, Margarornis squamiger MARGARORNINI Ruddy Treerunner, Margarornis rubiginosus Beautiful Treerunner, Margarornis bellulus Fulvous-dotted Treerunner / Star-chested Treerunner, Margarornis stellatus Cryptic Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti !Pale-browed Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes leucophrus Cinnamon-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor pyrrhodes Sharp-billed Treehunter, Philydor contaminatus !Black-capped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor atricapillus Alagoas Foliage-gleaner, Philydor novaesi Slaty-winged Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscipennis Rufous-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops erythrocercus Dusky-cheeked Foliage-gleaner / Bamboo Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops dorsalis !White-collared Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscus !Great Xenops, Megaxenops parnaguae Ochre-breasted Foliage-gleaner, Anabacerthia lichtensteini White-browed -

Behavior and Phylogenetic Position of Premnoplex Barbtails (Furnariidae)

The Condor 109:399–407 # The Cooper Ornithological Society 2007 BEHAVIOR AND PHYLOGENETIC POSITION OF PREMNOPLEX BARBTAILS (FURNARIIDAE) JUAN IGNACIO ARETA1,2,3 1CICyTTP-CONICET, Materi y Espan˜a, 3105, Diamante, Entre Rı´os, Argentina 2Grupo FALCO, El Coronillo, Reserva Natural Punta Lara, 1915, Ensenada, Buenos Aires, Argentina Abstract. The Margarornis assemblage includes four genera: Margarornis, Premno- plex, Premnornis, and Roraimia, all thought to be closely related. Differences in vocalizations and habitat use between Premnoplex brunnescens (Spotted Barbtail) and P. tatei (White-throated Barbtail) are consistent with their full species status. In light of the weak anatomical (hindlimb musculature) evidence supporting the inclusion of Premnornis in the Margarornis assemblage, the convergence-prone nature of characters associated with climbing habits, and the differences in their nests and foraging behavior, I propose that Premnornis is not a member of the Margarornis assemblage and that Premnoplex is closely related only to Margarornis. These results are supported by recent molecular phylogenetic analyses. Although Roraimia differs in plumage, tail shape, and song from other members of the Margarornis assemblage, it must be provisionally included in the assemblage until evidence clarifies its phylogenetic position. Key words: barbtails, behavior, convergence, morphology, nest, Premnoplex, Premnornis. Comportamiento y Posicio´n Filogene´tica de los Premnoplex (Furnariidae) Resumen. El ensamble Margarornis incluye cuatro ge´neros: -

The Spotted Barbtail (Premnoplex Brunnescens )

Greeney 1 Boletín SAO Vol. 18 Premnoplex brunnescens natural history in Ecuador (No. 1) Abril. 2008 – Pag: 1-9 The Spotted Barbtail (Premnoplex brunnescens): a review of taxonomy, distribution, and breeding biology, with additional observations from northeastern Ecuador Harold F. Greeney Yanayacu Biological Station & Center for Creative Studies, Cosanga, Napo, Ecuador. c/o 721 Foch y Amazonas, Quito, Ecuador. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Spotted Barbtail (Premnoplex brunnescens) is a poorly known ovenbird (Furnariidae) inhabiting the undergrowth of humid montane forests in Central and South America. Here I summarize published information on Spotted Barbtail as well as present observations from northeastern Ecuador. Both adults participate in all aspects of reproduction. Adults build and sleep in dormitories, similar in form to breeding nests. Mean egg size (n = 269) was 22.3 x 17.1 mm. Incubation lasted 27-31 days and nestlings fledged after 19-22 days. Nests are built exclusively along streams and potential threats to Spotted Barbtail populations include human alterations to montane stream ecosystems. Key words: Andes, cloud forest, foraging, Furnariidae, Margarornis assemblage, nest and eggs, Premnoplex brunnescens, Spotted Barbtail. Resumen El Subepalo Moteado (Premnoplex brunnescens) es un furnárido poco conocido que habita en el sotobosque de bosques húmedos de las montañas de Centro y Sur America. Aquí presento un resumen de la información publicada e inédita sobre esta especie. Ambos sexos participaron en todas las fases de la reproducción. Los adultos construyen y duermen en dormitorios que tienen formas parecidas a los nidos utilizados para la reproducción. Los huevos (n = 269) miden 22.3 x 17.1 mm. -

The Birds of Abra Patricia and the Upper Río Mayo, San Martín, North

T h e birds of Ab r a Patricia and the upper río Mayo, San Martín, north Peru Jon Hornbuckle Cotinga 12 (1999): 11– 28 En 1998 se llevó a cabo un inventario ornitológico en un bosque al este de Abra Patricia, Departamento San Martín, norte de Perú, en el cual se registraron 317 especies de aves. Junto con los registros previamente publicados y observaciones recientes realizadas por visitantes al área, el número de especies asciende a por lo menos 420. De éstas, 23 están clasificadas como amenazadas globalmente3, incluyendo Xenoglaux loweryi y Grallaricula ochraceifrons, ambas prácticamente desconocidas. Además, se registraron siete especies de distribución restringida. A pesar de que el ‘Bosque de Protección del Alto Mayo’ protege teóricamente 182 000 ha, la tala del bosque es una actividad frecuente y al parecer no existen medidas reales de control. En la actualidad se están realizando esfuerzos para conservar esta importante área. Introduction ochraceifrons10,15. However, ornithological surveys of In northern Peru, the forest east of the Abra Patricia this area have been confined to three Louisiana pass, dpto. San Martin (see Appendix 3 for State University Museum of Zoology (LSUMZ) coordinates) is of particular interest to expeditions, totalling six weeks: in 1976, 1977 and ornithologists as it is the type-locality for the near- 19835,15,18. Since that period the region has been too mythical Long-whiskered Owlet Xenoglaux loweryi dangerous to visit, until the recent cessation of and Ochre-fronted Antpitta Grallaricula guerilla activities. 11 Cotinga 12 The birds of Abra Patricia and the upper río Mayo, San M artín, north Peru The area is located at the northern end of the The habitat at the LSUMZ study sites has been Cordillera Oriental, the easternmost range of the described in some detail5,15,17 but can be summarised north Peruvian Andes, sloping eastward to the Rio at the lower elevations as subtropical forest of tall Mayo. -

Molecular Systematics of New World Suboscine Birds R

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com MOLECULAR SCIENCEENCE^I /W) DIRECT® PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION ELSEVIER Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32 (2004) 11-24 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Molecular systematics of New World suboscine birds R. Terry Chesser* Department of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79 th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA Received 12 February 2003; revised 14 November 2003 Available online 4 February 2004 Abstract Pliylogenetic relationships among New World suboscine birds were studied using nuclear and mitochondria! DNA sequences. New World suboscines were shown to constitute two distinct lineages, one apparently consisting of the single species Sapayoa aenigma, the other made up of the remaining 1000+ species of New World suboscines. With the exception oí Sapayoa, monophyly of New World suboscines was strongly corroborated, and monophyly within New World suboscines of a tyrannoid clade and a furnarioid clade was likewise strongly supported. Relationships among families and subfamilies within these clades, however, differed in several respects from current classifications of suboscines. Noteworthy results included: (1) monophyly of the tyrant- flycatchers (traditional family Tyrannidae), but only if the tityrines (see below) are excluded; (2) monophyly of the pipromorphine flycatchers (Pipromorphinae of Sibley and Ahlquist, 1990) as one of two primary divisions of a monophyletic restricted Tyrannidae; (3) monophyly of the tityrines, consisting of the genus Tityra plus all sampled species of the Schiffornis group (Prum and Lanyon, 1989), as sister group to the manakins (traditional family Pipridae); (4) paraphyly of the ovenbirds (traditional family Furnariidae), if woodcreepers (traditional family Dendrocolaptidae) are excluded; and (5) polyphyly of the antbirds (traditional family Formi- cariidae) and paraphyly of the ground antbirds (Formicariidae sensu stricto). -

New Bird Distributional Data from Cerro Tacarcuna, with Implications for Conservation in the Darién Highlands of Colombia

Luis Miguel Renjifo et al. 46 Bull. B.O.C. 2017 137(1) New bird distributional data from Cerro Tacarcuna, with implications for conservation in the Darién highlands of Colombia by Luis Miguel Renjifo, Augusto Repizo, Juan Miguel Ruiz-Ovalle, Sergio Ocampo & Jorge Enrique Avendaño Received 25 September 2016; revised 20 January 2017; published 13 March 2017 Summary.―We conducted an ornithological survey of the Colombian slope of Cerro Tacarcuna, the highland region adjacent to the ‘Darién Gap’ on the Colombia / Panama border, and one of the most poorly known and threatened regions in the world. We present novel data on distribution, habitat, breeding biology and vocalisations for 27 species, including the first confirmed records in Colombia of Ochraceous Wren Troglodytes ochraceus and Beautiful Treerunner Margarornis bellulus, and the first records in the Darién highlands of Black-headed Antthrush Formicarius nigricapillus, Scaly-throated Foliage-gleaner Anabacerthia variegaticeps, Yellow-throated Chlorospingus Chloropingus flavigularis hypophaeus and, based on previously overlooked specimens, report the first confirmed records for Colombia of Sooty-faced Finch Arremon crassirostris. In addition, we collected the first Colombian specimens of Violet-capped Hummingbird Goldmania violiceps, Bare- shanked Screech Owl Megascops clarkii, Tacarcuna Tapaculo Scytalopus panamensis and Varied Solitaire Myadestes coloratus. For several subspecies endemic to the region, we collected the first or second specimens for Colombia. Finally, we discuss the elevational ranges of Darién endemic species and subspecies, which are mostly concentrated above 600 m. The Darién highlands remain poorly studied and threats to their conservation are increasing. Therefore, effective measures are needed, particularly in Colombia, where the sole protected area in the region currently covers forests only below 600 m. -

AOU Check-List Supplement

AOU Check-list Supplement The Auk 117(3):847–858, 2000 FORTY-SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS’ UNION CHECK-LIST OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS This first Supplement since publication of the 7th Icterus prosthemelas, Lonchura cantans, and L. atricap- edition (1998) of the AOU Check-list of North American illa); (3) four species are changed (Caracara cheriway, Birds summarizes changes made by the Committee Glaucidium costaricanum, Myrmotherula pacifica, Pica on Classification and Nomenclature between its re- hudsonia) and one added (Caracara lutosa) by splits constitution in late 1998 and 31 January 2000. Be- from now-extralimital forms; (4) four scientific cause the makeup of the Committee has changed sig- names of species are changed because of generic re- nificantly since publication of the 7th edition, it allocation (Ibycter americanus, Stercorarius skua, S. seems appropriate to outline the way in which the maccormicki, Molothrus oryzivorus); (5) one specific current Committee operates. The philosophy of the name is changed for nomenclatural reasons (Baeolo- Committee is to retain the present taxonomic or dis- phus ridgwayi); (6) the spelling of five species names tributional status unless substantial and convincing is changed to make them gramatically correct rela- evidence is published that a change should be made. tive to the generic name (Jacamerops aureus, Poecile The Committee maintains an extensive agenda of atricapilla, P. hudsonica, P. cincta, Buarremon brunnein- potential action items, including possible taxonomic ucha); (7) one English name is changed to conform to changes and changes to the list of species included worldwide use (Long-tailed Duck), one is changed in the main text or the Appendix.