Virtual Worlds , Fiction, and Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chameleon Called Musical Time: Some Observations About Time and Musical Time

A chameleon called musical time: Some observations about time and musical time Thomas Reiner In The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann asks begin but merely starts. It does not build to a about the possibility of narrating time and gives an climax, does not purposefully set up internal example from music as part of his answer: expectations, does not seek to fulfill any expec- tations that might arise accidentally, does not Can one tell-that is to say, narrate-time, time build or release tension, and does not end but itself, as such, for its own sake? That would simply ceases.' surely be an absurd undertaking. A story which read: 'Time passed, it ran on, the time flowed Elaborating on the feeling of timelessness, onward' and so forth-no one in his senses Kramer states that it could consider that a narrative. It would be as though one held a single note or chord for a can be aroused not only by music but also whole hour, and called it music.' through other artforms, certain mental illnesses, dreams, unconscious mental processes, drugs, A single harmony is sustained for approximately and religious rituals. Vertical music does not 70 minutes in Stimmung, a work which Karlheinz create its own temporality but rather makes Stockhausen wrote in 1968. The work's title has contact with a deeply human time sense that is oflen denied in daily living (at least in Western several meanings and could be translated as tun- cultures). The significance of vertical composi- ing, intonation, atmosphere, or mood. The vocal- lions, and of many modernist anworks, is that ists in this composition sing the second, third, they give voice to a fundamental human experi- fourth, fifth, seventh, and riinth overtones of the ence that is largely unavailable in traditional fundamental note B flat. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

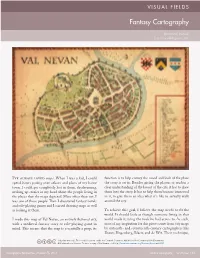

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

A Defense of FH Bradley's Philosophy of Experience Against William James' Criticisms By

The Experience of the Absolute: A Defense of F.H. Bradley’s Philosophy of Experience Against William James’ Criticisms By: Kyle Barbour Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Philosophy Department of Philosophy Memorial University August 2019 St. John’s, Newfoundland Page | 1 Abstract This thesis addresses the debate between two of the most important philosophers at the turn of the 20th century: F.H. Bradley and William James. Their debate centered around the priority that each philosopher assigned to experience in terms of a starting point for metaphysical inquiry and the subsequent understanding of logical relations which each philosopher developed based upon their conception of experience. This thesis will consider James’ “radical empiricism” as a response and critique of Bradley’s philosophy. As such, through an investigation of each philosopher, this thesis will argue that James’ critique of Bradley is flawed due to his misreading of Bradley’s philosophy and will conclude that Bradley’s philosophy holds the potential to answer the difficulties found within James’ radical empiricism and, though it contains undeniable flaws of its own, holds within it the seeds for future philosophical development that exceeds Bradley and James’ debate. Page | 2 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support of a number of people from both my personal and academic life. I would first like to thank Dr. Suma Rajiva and Dr. Seamus O’Neill for being constant supports throughout my entire time as a philosophy student at M.U.N. -

MAURICE MERLEAU-PONTY Translated by Forrest Williams

Study Project on the Nature of Perception (1933) The Nature of Perception (1934) MAURICE MERLEAU-PONTY Translated by Forrest Williams Translator's Preface On April 8, 1933, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who was then teaching at a lycée in Beauvais, applied to the Caisse National des Sciences for a subvention, which he received, to undertake a project of study on the nature of perception. In 1934, he requested a renewal, and submitted an account, which he titled 'The Nature of Perception," of what he had already accomplished and of what he proposed to do next. The renewal request was not granted. Apart from three book reviews and some remarks made at a philosophy conference, La Structure du Comportement, which was completed in 1938 and published in 1942, is generally considered the first evidence of Merleau-Ponty's major philosophical concerns. In a sense, that is so. However, the two earlier texts translated below, relatively short and schematic though they are, may never the less be of interest to students of Merleau-Ponty's philosophy. As can be shown, I think, by a brief analysis of their contents, Merleau-Ponty had ar- ticulated fairly clearly, some four years before the completion of Structure, a number of motifs that proved to be fundamental throughout his intellectual career. Naturally, his ideas were to expand and develop from 1933 to the drafts for Le Visible et l' invisible on 1 2 which he was working at the time of his death in 1961. Therefore, it is also interesting to notice themes of his later work that were not en- visaged at the outset. -

The Novel Map

The Novel Map The Novel Map Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction Patrick M. Bray northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2013 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2013. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Bray, Patrick M. The Novel Map: Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2013. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and the earlier version of chapter 4 as outlined in the Author’s Note For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Author’s Note xiii Introduction Here -

Final Thesis

A DEFENSE OF AESTHETIC ANTIESSENTIALISM: MORRIS WEITZ AND THE POSSIBLITY OF DEFINING ‘ART’ _____________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University _____________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy and Art History _____________________________ By Jordan Mills Pleasant June, 2010 ii This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Philosophy ___________________________ Dr. Arthur Zucker Chair, Department of Philosophy Thesis Advisor ___________________________ Dr. Scott Carson Honors Tutorial College, Director of Studies Philosophy ___________________________ Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College iii This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Art History ___________________________ Dr. Jennie Klein Chair, Department of Art History Thesis Advisor ___________________________ Dr. Jennie Klein Honors Tutorial College, Director of Studies Art History ___________________________ Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College iv Dedicated to Professor Arthur Zucker, without whom this work would have been impossible. v Table Of Contents Thesis Approval Pages Page ii Introduction: A Brief History of the Role of Definitions in Art Page 1 Chapter I: Morris Weitz’s “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics” Page 8 Chapter II: Lewis K. Zerby’s “A Reconsideration of the Role of the Theory in Aesthetics. A Reply to Morris Weitz” -

Towards a Contemporary Lutheran Aesthetics of Discipleship

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Concordia Seminary Scholarship 12-1-2018 The Eclipse of Elegance: Towards a Contemporary Lutheran Aesthetics of Discipleship Andrew Whaley Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/phd Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Whaley, Andrew, "The Eclipse of Elegance: Towards a Contemporary Lutheran Aesthetics of Discipleship" (2018). Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation. 63. https://scholar.csl.edu/phd/63 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECLIPSE OF ELEGANCE: TOWARDS A CONTEMPORARY LUTHERAN AESTHETICS OF DISCIPLESHIP A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Department of Systematic Theology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Andrew D. Whaley December, 2018 Approved by: Dr. Joel Biermann Dissertation Advisor Dr. Charles Arand Reader Dr. David Schmitt Reader © 2018 by Andrew D. Whaley. All rights reserved. ii To Jenna, Sam, and Kate: For all that jazz! iii “What we play is life.” Louis Armstrong iv CONTENTS PREFACE............................................................................................................................. -

Dissertation Final

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title LIterature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nj845hz Author Jones, Ruth Elizabeth Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 © Copyright by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille by Ruth Elizabeth Jones Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Patrick Coleman, Chair This dissertation is concerned with the construction of the image of the city in twentieth- century Francophone writing that takes as its primary objects the representation of the city in the work of Driss Chraïbi and Abdelkebir Khatibi (Casablanca), Francine Noël (Montreal), and Jean-Claude Izzo (Marseille). The different stylistic iterations of the post Second World War novel offered by these writers, from Khatibi’s experimental autobiography to Izzo’s noir fiction, provide the basis of an analysis of the connections between literary representation and the changing urban environments of Casablanca, Montreal, and Marseille. Relying on planning documents, historical analyses, and urban theory, as well as architectural, political, and literary discourse, to understand the fabric of the cities that surround novels’ representations, the dissertation argues that the perceptual descriptions that enrich these narratives of urban life help to characterize new ways of seeing and knowing the complex spaces of each of the cities. -

Fake Maps: How I Use Fantasy, Lies, and Misinformation to Understand Identity and Place

DOI: 10.14714/CP92.1534 VISUAL FIELDS Fake Maps: How I Use Fantasy, Lies, and Misinformation to Understand Identity and Place Lordy Rodriguez Represented by Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco [email protected] There were two maps that really influenced me as I was with the words Houston and New York in it, along with growing up in suburban Texas in the ’80s. The first was a number of other places that were important to me. Just a map of Middle Earth found in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The like the penciled maps I made in the fifth grade, I made Hobbit and the other was a map of the spice planet Arrakis more and more of them, but this time with a more de- from Frank Herbert’s Dune. Around fifth grade, I began veloped aesthetic language. I played around with text and to emulate those maps by creating my own based on imag- colors, and experimented with different media. It wasn’t ined planets and civilizations. They were crude drawings, long until I made the decision to start a long-term series made with a #2 pencil on typing paper. And I made tons based on this direction, which lasted for the next ten years: of them. I had a whole binder full of these drawings, with the America Series. countries that had names like Sh’kr—which, in my head, was pronounced sha-keer. Maps, so often meant to represent reality, instead solidified worlds of fantasy and fiction. Of course, I was not thinking critically about car- tography in this way when I was in grade school, but those fantasy maps laid the foundation for me to explore mapping again in the late ’90s. -

Middle Earth to Panem

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUPUIScholarWorks infoteCh Use a combination of books and technology to bring the world of Middle Earth maps alive for your students. BOOKS WITH MAPS IN THE SCHOOL LIBRARY to Panem School librarians can use the maps in popular books for children and young adults to jumpstart twenty-fi rst-century skills related Maps of Imaginary Places to analyzing primary sources, using online map and satellite im- age resources, and constructing maps. The Standards for the 21st as Invitations to Reading Century Learner stress the importance of understanding text in all formats, including maps. Maps play a supporting role in some books for youth, but in annette Lamb and Larry johnson others they are an integral part of the story line. In a study of chil- dren’s books, Jeffrey Patton and Nancy Ryckman (1990) identifi ed a continuum of purposes for maps, from simple to complex. At ogwarts, Panem, Middle Earth, one end of the spectrum, maps were used to illustrate the general and the Hundred Acre Wood . setting of the book. At the intermediate point, maps showed where the story occurred or how characters were connected to a setting. these may be fi ctional places, At the complex end of the continuum, the map explained spatial H elements of the story line, such as a character’s journey or clues but they are brought to life in books. While J. K. Rowling and Suzanne Col- in a mystery. Regardless of the author’s approach, book maps can be excit- lins chose to leave their worlds up to ing tools in teaching, learning, and promoting the joy of reading. -

The City As Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1979 The City as Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow Yashoda Nandan Singh Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Singh, Yashoda Nandan, "The City as Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow" (1979). Dissertations. 1839. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Yashoda Nandan Singh THE CITY AS METAPHOR IN SELECTED NOVELS OF JA..~S PURDY A...'ID SAUL BELLO\Y by Yashoda Nandan Singh A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School ', of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful to Professor Eileen Baldeshwiler for her guidance, patience, and discerning comments throughout the writing of this dissertation. She insisted on high intellectual standards and complete intelligibility, and I hope I have not disappointed her. Also, I must thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman and Gene D. Phillips, S.J., for serving on my dissertation committee and for their valuable suggestions. A word of thanks to Mrs. Jo Mahoney for her preparation of the final typescript.