Locating Lost City Radio by Meredith Perry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Desire for Perpetuation: Fairy Writing and Re-creation of National Identity in the Narratives of Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang Yuki Yoshino A Thesis Submitted to The University of Edinburgh for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that ‘fairy writing’ in the nineteenth-century Scottish literature serves as a peculiar site which accommodates various, often ambiguous and subversive, responses to the processes of constructing new national identities occurring in, and outwith, post-union Scotland. It contends that a pathetic sense of loss, emptiness and absence, together with strong preoccupations with the land, and a desire to perpetuate the nation which has become state-less, commonly underpin the wide variety of fairy writings by Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

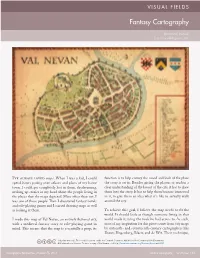

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

Avant La Lettre: Contradictory Affinities in Antonio Flores, Juan Bautista Amorós (Silverio Lanza) and Ángel Ganivet

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen's University Research Portal Avant la Lettre: Contradictory Affinities in Antonio Flores, Juan Bautista Amorós (Silverio Lanza), and Ángel Ganivet Lawless, G. (2018). Avant la Lettre: Contradictory Affinities in Antonio Flores, Juan Bautista Amorós (Silverio Lanza), and Ángel Ganivet. Modern Languages Open, (1), [13]. DOI: 10.3828/mlo.v0i0.180 Published in: Modern Languages Open Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2018 the author. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:06. -

The Porcupine and the End of History Oklukirpi Ve Tarihin Sonu

The Porcupine and the End of History Oklukirpi ve Tarihin Sonu Baysar Taniyan Pamukkale University, Turkey Abstract Set in a fictional East European country in the aftermath of the collapse of communism, Julian Barnes’s The Porcupine (1992) is a political satire where he juxtaposes two dominant ideologies; capitalist liberal democracy and communism. Although this short novel has a conventional narrative form, postmodern discussions on history can be observed, especially the discussion which has revolved around the idea of “the end of history”. It was Francis Fukuyama’s controversial article entitled “The End of History” (1989) that has sparked this specific debate. In 1992, he elaborated his thesis in a book titled The End of History and the Last Man, the same year Barnes published his novel. Fukuyama suggests that the modern Western liberal democracy is the ultimate and the most successful form of human government, the point where the Hegelian dialectic of history comes to an end. The aim of this article is to present a critical reading of the novel in the context of Fukuyama’s thesis and the discussion generated by this thesis. While it is true that Fukuyama’s thesis has now been outdated and negated, this reading may still provide fresh insights for the current political panorama of the world shaped by surging nationalism, increasing populism and growing conservatism. Keywords: Julian Barnes, The Porcupine, history, Francis Fukuyama, end of history Öz Komünizmin çöküşü sonrası kurgusal bir doğu Avrupa ülkesinde geçen Julian Barnes’ın Oklukirpi (1992) adlı romanı, kapitalist liberalizm ve komünizm gibi iki başat ideolojiyi karşı karşıya getiren politik bir hicivdir. -

The Novel Map

The Novel Map The Novel Map Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction Patrick M. Bray northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2013 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2013. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Bray, Patrick M. The Novel Map: Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2013. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and the earlier version of chapter 4 as outlined in the Author’s Note For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Author’s Note xiii Introduction Here -

Dissertation Final

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title LIterature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nj845hz Author Jones, Ruth Elizabeth Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 © Copyright by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille by Ruth Elizabeth Jones Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Patrick Coleman, Chair This dissertation is concerned with the construction of the image of the city in twentieth- century Francophone writing that takes as its primary objects the representation of the city in the work of Driss Chraïbi and Abdelkebir Khatibi (Casablanca), Francine Noël (Montreal), and Jean-Claude Izzo (Marseille). The different stylistic iterations of the post Second World War novel offered by these writers, from Khatibi’s experimental autobiography to Izzo’s noir fiction, provide the basis of an analysis of the connections between literary representation and the changing urban environments of Casablanca, Montreal, and Marseille. Relying on planning documents, historical analyses, and urban theory, as well as architectural, political, and literary discourse, to understand the fabric of the cities that surround novels’ representations, the dissertation argues that the perceptual descriptions that enrich these narratives of urban life help to characterize new ways of seeing and knowing the complex spaces of each of the cities. -

Fake Maps: How I Use Fantasy, Lies, and Misinformation to Understand Identity and Place

DOI: 10.14714/CP92.1534 VISUAL FIELDS Fake Maps: How I Use Fantasy, Lies, and Misinformation to Understand Identity and Place Lordy Rodriguez Represented by Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco [email protected] There were two maps that really influenced me as I was with the words Houston and New York in it, along with growing up in suburban Texas in the ’80s. The first was a number of other places that were important to me. Just a map of Middle Earth found in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The like the penciled maps I made in the fifth grade, I made Hobbit and the other was a map of the spice planet Arrakis more and more of them, but this time with a more de- from Frank Herbert’s Dune. Around fifth grade, I began veloped aesthetic language. I played around with text and to emulate those maps by creating my own based on imag- colors, and experimented with different media. It wasn’t ined planets and civilizations. They were crude drawings, long until I made the decision to start a long-term series made with a #2 pencil on typing paper. And I made tons based on this direction, which lasted for the next ten years: of them. I had a whole binder full of these drawings, with the America Series. countries that had names like Sh’kr—which, in my head, was pronounced sha-keer. Maps, so often meant to represent reality, instead solidified worlds of fantasy and fiction. Of course, I was not thinking critically about car- tography in this way when I was in grade school, but those fantasy maps laid the foundation for me to explore mapping again in the late ’90s. -

Middle Earth to Panem

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUPUIScholarWorks infoteCh Use a combination of books and technology to bring the world of Middle Earth maps alive for your students. BOOKS WITH MAPS IN THE SCHOOL LIBRARY to Panem School librarians can use the maps in popular books for children and young adults to jumpstart twenty-fi rst-century skills related Maps of Imaginary Places to analyzing primary sources, using online map and satellite im- age resources, and constructing maps. The Standards for the 21st as Invitations to Reading Century Learner stress the importance of understanding text in all formats, including maps. Maps play a supporting role in some books for youth, but in annette Lamb and Larry johnson others they are an integral part of the story line. In a study of chil- dren’s books, Jeffrey Patton and Nancy Ryckman (1990) identifi ed a continuum of purposes for maps, from simple to complex. At ogwarts, Panem, Middle Earth, one end of the spectrum, maps were used to illustrate the general and the Hundred Acre Wood . setting of the book. At the intermediate point, maps showed where the story occurred or how characters were connected to a setting. these may be fi ctional places, At the complex end of the continuum, the map explained spatial H elements of the story line, such as a character’s journey or clues but they are brought to life in books. While J. K. Rowling and Suzanne Col- in a mystery. Regardless of the author’s approach, book maps can be excit- lins chose to leave their worlds up to ing tools in teaching, learning, and promoting the joy of reading. -

The City As Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1979 The City as Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow Yashoda Nandan Singh Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Singh, Yashoda Nandan, "The City as Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow" (1979). Dissertations. 1839. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Yashoda Nandan Singh THE CITY AS METAPHOR IN SELECTED NOVELS OF JA..~S PURDY A...'ID SAUL BELLO\Y by Yashoda Nandan Singh A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School ', of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful to Professor Eileen Baldeshwiler for her guidance, patience, and discerning comments throughout the writing of this dissertation. She insisted on high intellectual standards and complete intelligibility, and I hope I have not disappointed her. Also, I must thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman and Gene D. Phillips, S.J., for serving on my dissertation committee and for their valuable suggestions. A word of thanks to Mrs. Jo Mahoney for her preparation of the final typescript. -

Narrative in Herman Melville's Moby Dick

Narrative in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick Traugott and Pratt define narration as ‘essentially a way of linguistically representing past experience, whether real or imagined’ (1980: 248). The mode of the teller inevitably affects every aspect of the representation of story. Toolan states that the inherent nature of narrative text as spatially and temporally distant to the reader inevitably leads to a ‘sense of the detachment’ and ‘cutoffnesss’ (1988: 6). This study will assert that narrative mode can decrease this sense of disconnection between reader and the text. Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is a good example of a strong narratorial presence that seeks to place itself in close proximity with the reader. The intrusive style of narration caused controversy at the time of the novel’s publication, with one reviewer claiming that, ‘there is so much eccentricity in its style and in its construction… that we are at a loss to determine in what category of works of amusement to place it’ (Parker and Hayford (eds.) 1970: 22). In the opening extract of the novel ‘narrative trajectory’ (Toolan 19188: 6) has not begun, instead the text remains on the level of discourse, allowing for the development of the narrator’s manner of telling. This study will examine the unusual narrative mode of Moby Dick and demonstrate how narratology can create a sense of closeness between the ‘speaker’, in this case Ishmael, and the reader, disproving Toolan’s assertion. The narrator of Moby Dick begins the text with his introduction, ‘call me Ishmael’ (1851:1) which immediately establishes a first person narrator, indicated by the first person singular pronoun, ‘me’. -

“I Love You 3000” an Analysis of the Marvel Cinematic Universe

Emilie Højer Jørgensen and Maya Majgaard Herr Steen Ledet Christiansen Engelsk speciale 2 June 2020 Aalborg University “I love you 3000” An analysis of the Marvel Cinematic Universe Jørgensen & Herr 2 Abstract In this thesis, we will examine if the Marvel Cinematic Universe can be considered complex. We will analyse the following films Captain America: Civil War, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, and Avengers: Endgame which are all from Marvel Cinematic Universe’s third phase. We have chosen these films because they are connected in terms of storylines, characters, and worlds. We will focus on transmedia storytelling, seriality, kernels and satellites, worldbuilding, and complex media in order to examine the complexities within the films. Traditionally, transmedia storytelling is defined as one continuous story across multiple instalments and platforms. Two important aspects of transmedia storytelling are seriality and worldbuilding, where seriality deals with how stories are told across instalments and worldbuilding deals with how a fictional world is created and what it takes to make a fictional world believable. Kernels and satellites deal with major and minor events that occur in a narrative text and how they impact each other and complex media deals with how popular culture is becoming more and more complex because of multiple storylines that occur in different mediums. It is through these concepts that we will analyse the complexities within the films. Civil War and the two Avengers films are very serial because they are linked together through information and events that continue from previous films. The three films require the viewers to be familiar with the universe beforehand because they rely heavily on characters, storylines, and events from previous films.