Dissertation Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murder in Aubagne: Lynching, Law, and Justice During the French

This page intentionally left blank Murder in Aubagne Lynching, Law, and Justice during the French Revolution This is a study of factions, lynching, murder, terror, and counterterror during the French Revolution. It examines factionalism in small towns like Aubagne near Marseille, and how this produced the murders and prison massacres of 1795–1798. Another major theme is the conver- gence of lynching from below with official terror from above. Although the Terror may have been designed to solve a national emergency in the spring of 1793, in southern France it permitted one faction to con- tinue a struggle against its enemies, a struggle that had begun earlier over local issues like taxation and governance. This study uses the tech- niques of microhistory to tell the story of the small town of Aubagne. It then extends the scope to places nearby like Marseille, Arles, and Aix-en-Provence. Along the way, it illuminates familiar topics like the activity of clubs and revolutionary tribunals and then explores largely unexamined areas like lynching, the sociology of factions, the emer- gence of theories of violent fraternal democracy, and the nature of the White Terror. D. M. G. Sutherland received his M.A. from the University of Sussex and his Ph.D. from the University of London. He is currently professor of history at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is the author of The Chouans: The Social Origins of Popular Counterrevolution in Upper Brittany, 1770–1796 (1982), France, 1789–1815: Revolution and Counterrevolution (1985), and The French Revolution, 1770– 1815: The Quest for a Civic Order (2003) as well as numerous scholarly articles. -

MARSEILLE MARSEILLE 2018 MARSEILLE Torsdag 4/10

MARSEILLE MARSEILLE 2018 MARSEILLE Torsdag 4/10 4 5 6 Transfer till Arlanda Flyg 7 Fredag 5/10 Lördag 6/10 Söndag 7/10 8 9 10 Med guide: Picasso museum Med guide: 11 Les Docks Libres i Antibes Euromediterranée Quartiers Libres Förmiddag 12 Lunch @ Les illes du Micocoulier Transfer till 13 Nice Lunch @ Lunch på egen hand Flyg 14 Transfer till La Friche Belle de Mai Arlanda Express Marseille 15 Egen tid Med guide: Vårt förslag: Yes we camp! 16 La Cité Radieuse FRAC, Les Docks, Le Silo Parc Foresta Le Corbusier Smartseille 17 La Marseillaise Etermiddag CMA CGM Tillträde till MUCEM 18 Transfer till hotellet (Ai Weiwei) Check-in Egen tid 19 20 Middag @ La Mercerie 21 Middag @ Middag @ Sepia La Piscine Kväll 22 23 Since Marseille-Provence was chosen to be the European Capital of Culture in 2013, the Mediterranean harbour city has become a very atracive desinaion on the architectural map of the world. Besides new spectacular cultural buildings along the seashore, the city has already for a long ime been in a comprehensive process of urban transformaion due to Euroméditerranée, the large urban development project. Under the inluence of the large-scale urban development project of the city, the Vieux Port (Old Harbour) was redesigned 2013 by Norman Foster and several new cultural buildings were realised: amongst others the MuCEM – Museum for European and Mediterranean Civilisaions (Arch. Rudy Riccioi), the Villa Méditerranée (Arch. Stefano Boeri) as well as the FRAC – Regional Collecion of contemporary Art (Arch. Kengo Kuma), which today are regarded as lagship projects of the city. -

On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau

Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau To cite this version: Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction. 2003. hal-02320291 HAL Id: hal-02320291 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02320291 Submitted on 14 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Gérard BREY (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Foreword ..... 9 Philippe LAPLACE & Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche- Comté, Besançon), Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities ......... 11 Richard SKEATES (Open University), "Those vast new wildernesses of glass and brick:" Representing the Contemporary Urban Condition ......... 25 Peter MILES (University of Wales, Lampeter), Road Rage: Urban Trajectories and the Working Class ............................................................ 43 Tim WOODS (University of Wales, Aberystwyth), Re-Enchanting the City: Sites and Non-Sites in Urban Fiction ................................................ 63 Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Marginally Correct: Zadie Smith's White Teeth and Sam Selvon's The Lonely Londoners .................................................................................... -

The Foreign Service Journal, September 1936

g/,< AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE * * JOURNAL * * Manhattan's Biggest Hotel The Hotel New Yorker is big even for the city of skyscrapers, but the service you get is warmly personal and attentive. Our guests are kind enough to tell us that we’ve learned well the art of making folks feel at home. There are 2,500 rooms . each with tub and shower bath, radio, Servidor, circulating ice water . luxuriously furnished and equipped with beds designed for deep, restful slumber. The four air conditioned restaurants are noted for the excellence of food and drink and for reasonable prices. Right in the heart of mid-town Manhattan, we are near the leading theatres and department stores; with our own private tunnel to the Pennsylvania Station and subway. Nowhere else will you find such values as the New Yorker offers you; with a large number of rooms for as little as $3.00. For good business, for good living, for good times, come stay with us at the Hotel New Yorker. 25% reduction to diplomatic and consular service NOTE: The special rate reduction applies only to rooms on which rate is $4 a day or more. HOTEL NEW YORKER 34th Street at Eighth Avenue New York City Directed by Ralph Hitz, President Private Tunnel from Pennsylvania Station The nearest fine hotel to all New York piers Other Hotels Under Direction of National Hotel management Co., Inc., Ralph Hitz, President NETHERLAND PLAZA. CINCINNATI : BOOK-CADILLAC, DETROIT : CONGRESS HOTEL, CHICAGO HOTEL VAN CLEVE, DAYTON : HOTEL ADOLPHUS, DALLAS ! HOTEL NICOLLET, MINNEAPOLIS THE AMERICAN pOREIGN gERVICE JOURNAL CONTENTS (SEPTEMBER, 1936) COVER PICTURE GRACE LINE Camel Rider, Algiers (See also page 534) "SANTA" SHIPS SERVE PAGE THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES NEW YORK By Elizabeth M. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

Fantasy Cartography

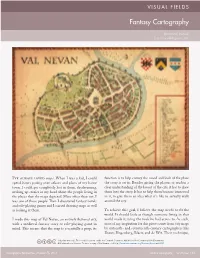

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

V MEET FILM FESTIVAL Meet Flm Festival

V MEET FILM FESTIVAL meet flm festival 2 catalogo MEET FILM FESTIVAL V EDIZIONE Il MEET FILM FESTIVAL (Movies for European Education and territorio di Garbatella e che ci hanno aiutato ad accogliere e Training) è un punto d’incontro italiano per i cortometraggi, diffondere i film arrivati al Festival: provenienti da tutto il mondo, che interpretano in modo originale il TEATRO GARBATELLA e l’associazione ZERO IN CONDOTTA- i temi del cinema, della scuola, dei giovani, della didattica e della Film Club (via Caffaro n. 10), nei quali si proiettano i film finalisti formazione. alla presenza dei registi; il MILLEPIANI COWORKING (via N. La sua quinta edizione si tiene per la prima volta a Roma, dal 23 Odero n. 13), dove si svolgono incontri e dibattiti con professori, al 27 settembre, con epicentro al TEATRO GARBATELLA (piazza studenti ed esperti del settore cinematografico; La VILLETTA Giovanni da Triora n. 15), dove si proiettano i 49 film finalisti tra (via F. Passino n. 26 e via degli Armatori n. 3), che ospita proiezioni gli oltre 1800 arrivati da più di 100 Paesi di tutto il mondo. serali all’aperto alla presenza degli autori, con le rassegne: “Distruzione e Istruzione (bambini e guerra)”, “Migrazioni”, La giuria del Festival è composta da professionisti del cinema “Social Media”, “I vincitori del Festival”. e del mondo della scuola, quest’anno presieduta dal regista, sceneggiatore e produttore romano Gianfrancesco Lazotti. La rassegna “Distruzione e Istruzione (bambini e guerra)” La giuria è chiamata a scegliere i vincitori tra i finalisti delle offre al pubblico romano un’occasione irripetibile di vedere quattro sezioni in concorso (EDUCATION EUROPE-sezione A: appassionanti storie di minori in Iraq, Siria, Turchia, Palestina, e opere realizzate da scuole europee su tema libero; YOUTH AND Iran, storie che faticano spesso ad uscire dai territori difficili in cui TRAINING EUROPE-sezione A2: opere su scuola, formazione e sono state filmate e ad avere la possibilità di essere apprezzate. -

Design the Definitive Visual History by DK

Design The Definitive Visual History by DK You're readind a preview Design The Definitive Visual History book. To get able to download Design The Definitive Visual History you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited books*. Accessible on all your screens. *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every file is in the library. But if You are still not sure with the service, you can choose FREE Trial service. Book Details: Review: Best book I have ever seen on the design of an extraordinarily wide range of works from 1850 to the present! Extraordinary photos, wonderful biographies of key designers, clear and intelligent grouping of works into eras and styles. Awesome diversity, including almost every aspect of items shaping our lives: furniture, lights, appliances, tableware,... Original title: Design: The Definitive Visual History 480 pages Publisher: DK (October 6, 2015) Language: English ISBN-10: 1465438017 ISBN-13: 978-1465438010 Product Dimensions:10.2 x 1.4 x 12.1 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 20158 kB Ebook Tags: Description: Design: The Definitive Visual History lays out the complete evolution of design, from its origins in early cultures to the contemporary design — physical and digital — of today. This comprehensive volume covers every major design movement, along with the iconic designers and manufacturers who influenced everyday life through the objects and buildings... Design The Definitive Visual History by DK ebooks - Design The Definitive Visual History design visual the definitive pdf definitive visual design the history fb2 definitive history the design visual ebook the definitive visual history design book Design The Definitive Visual History The Definitive Visual History Design She provides definitive information about theyear ahead and into the future. -

Casablanca Finance City

CASABLANCA FINANCE CITY Your Gateway to Africa’s Potential CFC Presentation 1 2 Presentation 3 AFRICA IS ARISING AS THE WORLD’S FASTEST GROWING CONTINENT WITH TREMENDOUS OPPORTUNITIES 24 African countries will grow at a CAGR of at least 5% by 2030 Casablanca Tunisia 3 out of 4 newborns in 2100 Morocco 70% of African households will have a purchasing power will be African Algeria Libya Egypt higher than $50001 in 2025 Mauritania Mali Niger Senegal Chad Eritrea Gambia Djibouti Sudan Guinea Bissau Burkina Guinea Sierra Central Somalia Ghana Nigeria Ethiopia Leone Ivory African Liberia Coast Republic Cameroon Benin Uganda Equatorial DRC Kenya TogoGuinea Gabon Rwanda Congo Booming working age Burundi Tanzania population Increasing urbanisation: Malawi Mozambique 100 African cities with over 1 Angola Zambia million inhabitants in 2025 Comoros Zimbabwe Namibia Botswana Madagascar Swaziland Lesotho South Africa Massive infrastructure needs: ~$90 billion dollars/year until 4 2020 1: In purchasing power parity MOROCCO HOLDS A STRONG POSITION AS A HUB, THANKS TO ITS: STRATEGIC ADVANTAGES • Political stability • World class infrastructure • Air connectivity • Privileged geographical position STRONG PRESENCE IN AFRICA DISTINGUISHED ECONOMIC FUNDAMENTALS • Several Moroccan companies rooted • Macroeconomic stability in Africa • Investment grade • Strong financial sector • Free trade agreements giving • Multisectoral experience access to a market of more than one billion consumers 5 WHAT IS THE AIM OF CASABLANCA FINANCE CITY (CFC)? ... for 4 types of -

The History and Description of Africa and of the Notable Things Therein Contained, Vol

The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.nuhmafricanus3 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 Alternative title The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained Author/Creator Leo Africanus Contributor Pory, John (tr.), Brown, Robert (ed.) Date 1896 Resource type Books Language English, Italian Subject Coverage (spatial) Northern Swahili Coast;Middle Niger, Mali, Timbucktu, Southern Swahili Coast Source Northwestern University Libraries, G161 .H2 Description Written by al-Hassan ibn-Mohammed al-Wezaz al-Fasi, a Muslim, baptised as Giovanni Leone, but better known as Leo Africanus. -

Obtic01c 6DAYS/5NIGHTS CASABLANCA/RABAT/MEKNES-VOLUBILIS-FES/MARRAKECH/CASABLANCA

OBTIC01c 6DAYS/5NIGHTS CASABLANCA/RABAT/MEKNES-VOLUBILIS-FES/MARRAKECH/CASABLANCA DAY 1: CASABLANCA. You will be met on arrival Casablanca airport by your English-speaking National Guide and transferred to your hotel. As your arrival may be rather early, we shall arrange for you to check-in and relax after your long journey until 11:00 when you will be taken for a tour of this bustling metropolis to visit the exterior of the Dar el Makhzen, or King’s Palace, with its magnificent doors, the New Medina – or Habous area – designed by French architects in the 1930s to resolve a housing crisis and create a modern, twentieth century Kasbah - here to stroll through the reasonably-modern (1923) souk and on past the Pasha’s Mahakma Court of Islamic Law. A visit may be made (previous advice required) to the Beth-El Synagogue, one of the largest and most beautiful noted for its stained glass windows, in the style of Marc Chagall. Sunlight, tinted by stained glass, bounces off a gigantic crystal chandelier creating thousands of shimmering rainbow mosaics on every surface. The ark, the most important thing in the synagogue, houses the Hebrew scrolls and these are dressed in exquisitely embroidered velvet mantles. The walls are inscribed with gilded quotes from the Bible and the ceiling is equally decorative. We continue on to the elegant residential district of Anfa, the original site of Casablanca, with its green parks and Art Deco villas. Anfa hosted the Conference of Casablanca with President Roosevelt and Sir Winston Churchill, during which the date of the Allied landings on the French coasts was fixed for the spring of 1944 and where the somewhat difficult meeting with them and Generals Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giraud took place. -

Using Urban Fiction to Engage Atrisk and Incarcerated Youths in Literacy

Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 55(5) February 2012 doi:10.1002/JAAL.00047 © 2012 International Reading Association (pp. 385–394) Using Urban Fiction to Engage At-Risk and Incarcerated Youths in Literacy Instruction How can we select Stephanie F. Guerra literature that will appeal to at-risk and incarcerated On any given day, more than 100,000 youths are incarcerated in the United States (Snyder & Sickmund, 2006). Countless more are considered teens—and meet the “at-risk” for incarceration, based on factors such as homelessness, poverty, requirements for use in gang membership, substance abuse, grade retention, and more. Unfortunately, gender and race can be considered risk factors as well. correctional facilities and The most recent Department of Justice (DOJ) census showed that 85% of high schools? incarcerated teens are male (Snyder & Sickmund, 2006). Thirty-eight percent of the youths in the juvenile justice system are black, and 19% are Hispanic (Snyder & Sickmund, 2006). The DOJ predicted that the juvenile correctional population will increase by 36% by the year 2020, mostly because of growth in the Hispanic male population (Snyder & Sickmund, 2006). Research points to literacy as a major protective factor against incarceration for at-risk youths (Christle & Yell, 2008), while reading difficulty has been documented as one of the leading risk factors for delinquency (Brunner, 1993; Drakeford, 2002; Leone, Krezmien, Mason, & Meisel, 2005; Malmgren & Leone, 2000). For teens already in custody, literacy skills are strongly correlated with a lower chance of recidivism (Leone et al., 2005). In fact, reading instruction has been more effective than shock incarceration or boot camps at reducing recidivism (Center on Crime, Communities, and Culture, 1997).