Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Monkeys Episode Guide Episodes 001–036

12 Monkeys Episode Guide Episodes 001–036 Last episode aired Sunday May 21, 2017 www.syfy.com c c 2017 www.tv.com c 2017 www.syfy.com c 2017 www.imdb.com c 2017 www.nerdist.com c 2017 www.ew.com The summaries and recaps of all the 12 Monkeys episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http: //www.syfy.com and http://www.imdb.com and http://www.nerdist.com and http://www.ew.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on June 28, 2017 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.59 Contents Season 1 1 1 Splinter . .3 2 Mentally Divergent . .5 3 Cassandra Complex . .7 4 Atari...............................................9 5 The Night Room . 11 6 The Red Forest . 13 7 The Keys . 15 8 Yesterday . 17 9 Tomorrow . 19 10 Divine Move . 23 11 Shonin . 25 12 Paradox . 27 13 Arms of Mine . 29 Season 2 31 1 Year of the Monkey . 33 2 Primary . 35 3 One Hundred Years . 37 4 Emergence . 39 5 Bodies of Water . 41 6 Immortal . 43 7 Meltdown . 45 8 Lullaby . 47 9 Hyena.............................................. 49 10 Fatherland . 51 11 Resurrection . 53 12 Blood Washed Away . 55 13 Memory of Tomorrow . 57 Season 3 59 1 Mother . 61 2 Guardians . 63 3 Enemy.............................................. 65 4 Brothers . 67 5 Causality . 69 6 Nature.............................................. 71 7 Nurture . 73 8 Masks.............................................. 75 9 Thief............................................... 77 10 Witness -

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

This Cover and Their Final Version Extended

then this cover and their final version extended and whether it is group 1 or Peterson :_:::_.,·. ,_,_::_ ·:. -. \")_>(-_>·...·,: . .>:_'_::°::· ··:_-'./·' . /_:: :·.·· . =)\_./'-.:":_ .... -- __ · ·, . ', . .·· . Stlpervisot1s t~pe>rt ~fld declaration J:h; s3pervi;o(,r;u~f dompietethisreport,. .1ign .the (leclaratton andtfien iiv~.ihe pna:1 ·tersion·...· ofth€7 essay; with this coyerattachedt to the Diploma Programme coordinator. .. .. .. ::,._,<_--\:-.·/·... ":";":":--.-.. ·. ---- .. ,>'. ·.:,:.--: <>=·. ;:_ . .._-,..-_,- -::,· ..:. 0 >>i:mi~ ~;!~;:91'.t~~~1TAt1.tte~) c P1~,§.~p,rmmeht, ;J} a:,ir:lrapriate, on the candidate's perforrnance, .111e. 9q1Jtext ·;n •.w111ctrth~ ..cahdtdatei:m ·.. thft; J'e:~e,~rch.·forf fle ...~X: tendfKI essay, anydifflcu/ties ef1COUntered anq ftCJW thes~\WfJ(fj ()VfJfCOfflf! ·(see .· •tl1i! ext~nciede.ssay guide). The .cpncl(ldipg interview .(vive . vope) ,mt;}y P.fOvidtli .US$ftJf .informf.ltion: pom1r1~nt~ .can .flelp the ex:amr1er award.a ··tevetfot criterion K.th9lisJtcjudgrpentJ. po not. .comment ~pverse personal circumstan9~s that•· m$iiybave . aff.ected the candidate.\lftl'1e cr.rrtotJnt ottime.spiimt qa;ndidate w~s zero, Jt04 must.explain tf1is, fn particular holft!1t was fhf;Jn ppssible .to ;;1.uthentic;at? the essa~ canciidaJe'sown work. You rnay a-ttachan .aclditfonal sherJtJf th.ere isinspfffpi*?nt f pr1ce here,·.···· · Overall, I think this paper is overambitious in its scope for the page length / allowed. I ~elieve it requires furt_her_ editing, as the "making of" portion takes up too ~ large a portion of the essay leaving inadequate page space for reflections on theory and social relevance. The section on the male gaze or the section on race relations in comedy could have served as complete paper topics on their own (although I do appreciate that they are there). -

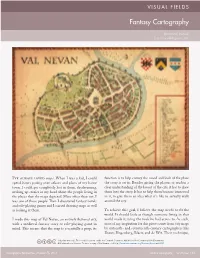

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

2019 National Sports and Entertainment History Bee Round 2

Sports and Entertainment Bee 2018-2019 Prelims 2 Prelims 2 Regulation (Tossup 1) This man stars in an oft-parodied commercial in which he states \Ballgame" before taking a drink of Gatorade Flow. In 2017, this man's newly acquired teammate told him \they say I gotta come off the bench." This man missed nearly the entire 2014-2015 season after suffering a horrific leg injury while practicing for the US National Team. Sam Presti sent Domantas Sabonis and Victor Oladipo to the Indiana Pacers in exchange for this player, who then surprisingly didn't bolt to the Lakers in the 2018 off-season. For the point, name this player who formed an unsuccessful \Big Three" with Carmelo Anthony and Russell Westbrook on the Oklahoma City Thunder. ANSWER: Paul Clifton Anthony George (accept PG13) (Tossup 2) This series used Ratatat's \Cream on Chrome" as background music for many early episodes. Side projects of this series include a \Bedtime" version featuring literature readings and an educational \Basics" version. This series' 2019 April Fools' Day gag involved the a 4Kids dub of Pokemon claiming that Brock loved jelly donuts. This series celebrated million-subscriber benchmarks with episodes featuring the Taco Town 15-layer taco and the Every-Meat Burrito and Death Sandwich from Regular Show. For the point, name this YouTube channel starring Andrew Rea, who cooks various foods as inspired by popular culture. ANSWER: Binging with Babish (Tossup 3) The creators of this game recently announced a \Royal" edition which will add a third semester of gameplay. In April 2019, a heavily criticzed Kotaku article claimed that this game's theme song, \Wake up, Get up, Get out there," contains a slur against people with learning disabilities. -

Philip Krachun

THE MYTH OF THE THOUSAND WORDS: EXPLORING THE ROLE OF NARRATIVE IN LA JETÉE AND 12 MONKEYS Philip Krachun So they say that a picture is worth a thousand words, that the camera never lies. These are maxims that have followed us through childhood with little more than a casual thought in their direction. People eventually start thinking that pictures take on some kind of narrative voice all their own in the false hope that a picture is worth a thousand words, when in reality, a picture is nothing without some kind of context. Photographer Chris Marker recognized this dilemma and incorporated it into the film La Jetée, which would later form the basis for Terry Gilliam’s comment on the role of intrinsic meaning 12 Monkeys . What is a picture but a symbol? A photograph is little more than a moment arrested in time, a shot plucked from the environment by a wary photographer. It is little more than a record of light, technically speaking, but can photographs have another dimensionmeaning? In an essay entitled “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning,” Allan Sekula states that “The photograph is imagined to have a primitive core of meaning . and] is a sign, above all, of someone’s investment in the sending of a message” (87). This seems to suggest that photography is another means of discourse, which is to say that thoughts and ideas can be expressed through pictures. There is some credibility to the claim that a picture is worth a thousand words; simply acknowledging a motive in the creation of a thing implies meaning on some level; the picture definitely has something to say, even if the maxim is not taken literally. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

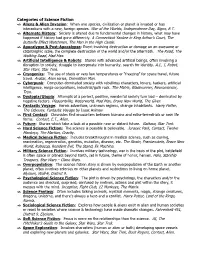

Categories of Science Fiction Aliens & Alien Invasion: When One Species, Civilization Or Planet Is Invaded Or Has Interactions with a New, Foreign Species

Categories of Science Fiction Aliens & Alien Invasion: When one species, civilization or planet is invaded or has interactions with a new, foreign species. War of the Worlds, Independence Day, Signs, E.T. Alternate History: Society is altered due to fundamental changes in history, what may have happened if history had gone differently. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, The Butterfly Effect Watchmen, The Man in the High Castle. Apocalypse & Post-Apocalypse: Event involving destruction or damage on an awesome or catastrophic scale, the complete destruction of the world and/or the aftermath. The Road, The Walking Dead, Mad Max. Artificial Intelligence & Robots: Stories with advanced artificial beings, often involving a disruption to society, struggle to incorporate into humanity, search for identity. A.I., I, Robot, Star Wars, Star Trek. Cryogenics: The use of stasis or very low temperatures or “freezing” for space travel, future travel. Avatar, Alien series, Demolition Man. Cyberpunk: Computer-dominated society with rebellious characters, loners, hackers, artificial intelligence, mega-corporations, industrial/goth rock. The Matrix, Bladerunner, Neuromancer, Tron. Dystopia/Utopia: Attempts at a perfect, positive, wonderful society turn bad – dominated by negative factors. Pleasantville, Waterworld, Mad Max, Brave New World, The Giver. Fantastic Voyage: Heroic adventure, unknown regions, strange inhabitants. Harry Potter, The Odyssey, Fantastic Voyage by Isaac Asimov First Contact: Chronicles first encounters between humans and extra-terrestrials or new life forms. Contact, E.T., Alien. Future: Stories which take a look at a possible near or distant future. Gattaca, Star Trek. Hard Science Fiction: The science is possible & believable. Jurassic Park, Contact, Twelve Monkeys, The Martian, Gravity. -

The Representation Of'paranoia'in the Films of Terry Gilliam

AN APPROACH OF MISTRUST: THE REPRESENTATION OF‘PARANOIA’IN THE FILMS OF TERRY GILLIAM A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF GRAPHIC DESIGN AND THE INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS OF BILKENT UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS By Ece Pazarbaşı May, 2001 I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. _____________________________________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Nezih Erdoğan (Principal Advisor) I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. __________________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Mahmut Mutman I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. ____________________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. John Robert Groch Approved by the Institute of Fine Arts __________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Bülent Özgüç, Director of the Institute of Fine Arts ii ABSTRACT AN APPROACH OF MISTRUST: REPRESENTATION OF ‘PARANOIA’ IN TERRY GILLIAM’S FILMS Ece Pazarbasi M.F.A. in Graphic Design Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Nezih Erdogan May, 2001 This study aims at investigating the representation on ‘paranoia’ in the films, 12 Monkeys (1995), Brazil (1985), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989), and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), by Terry Gilliam. The paranoid state in the films come into being both in the digesis and in the journey from Terry Gilliam’s vision to the audience. -

The Novel Map

The Novel Map The Novel Map Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction Patrick M. Bray northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2013 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2013. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Bray, Patrick M. The Novel Map: Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2013. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and the earlier version of chapter 4 as outlined in the Author’s Note For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Author’s Note xiii Introduction Here -

Dissertation Final

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title LIterature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nj845hz Author Jones, Ruth Elizabeth Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 © Copyright by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille by Ruth Elizabeth Jones Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Patrick Coleman, Chair This dissertation is concerned with the construction of the image of the city in twentieth- century Francophone writing that takes as its primary objects the representation of the city in the work of Driss Chraïbi and Abdelkebir Khatibi (Casablanca), Francine Noël (Montreal), and Jean-Claude Izzo (Marseille). The different stylistic iterations of the post Second World War novel offered by these writers, from Khatibi’s experimental autobiography to Izzo’s noir fiction, provide the basis of an analysis of the connections between literary representation and the changing urban environments of Casablanca, Montreal, and Marseille. Relying on planning documents, historical analyses, and urban theory, as well as architectural, political, and literary discourse, to understand the fabric of the cities that surround novels’ representations, the dissertation argues that the perceptual descriptions that enrich these narratives of urban life help to characterize new ways of seeing and knowing the complex spaces of each of the cities. -

New Years Eve Films

Movies to Watch on New Year's Eve Going Out Is So Overrated! This year, New Year’s Eve celebrations will have to be done slightly differently due to the pandemic. So, the Learning Curve thought ‘Why not just ring in 2021 with some feel-good movies in your comfy PJs instead?’ After all, everyone knows that the best way to turn over a new year is snuggled up in front of the TV with a hot beverage in your hand. The good news is, no matter how you want to feel going into the next year, there’s a movie on this list that’ll deliver. Best of all — you won’t wake up the next day and begin January with a hangover! Godfather Part II (1974) Director: Francis Ford Coppola Starring: Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Robert Duvall Continuing the saga of the Corleone crime family, the son, Michael (Pacino) is trying to expand the business to Las Vegas, Hollywood and Cuba. They delve into double crossing, greed and murder as they all try to be the most powerful crime family of all time. Godfather part II is hailed by fans as a masterpiece, a great continuation to the story and the best gangster movie of all time. This is a character driven movie, as we see peoples’ motivations, becoming laser focused on what they want and what they will do to get it. Although the movie is a gripping slow crime drama, it does have one flaw, and that is the length of the movie clocking in at 3 hours and 22 minutes.