The City As Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideological Tension in Four Novels by Saul Bellow

Ideological Tension in Four Novels by Saul Bellow June Jocelyn Sacks Dissertation submitted in fulfilmentTown of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts atCape the Universityof of Cape Town Univesity Department of English April 1987 Supervisor: Dr Ian Glenn The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Contents Page. Abstract i Acknowledgements vi Introduction Chapter One Dangling Man 15 Chapter Two The Victim 56 Chapter Three Herzog 99 Chapter Four Mr Sammler's Planet 153 Notes 190 Bibliography 212 Abstract This study examines and evaluates critically four novels by Saul Bellow: Dangling Man, The Victim, Herzog and Mr Sammler's Planet. The emphasis is on the tension between certain aspects of modernity to which many of the characters are attracted, and the latent Jewishness of their creator. Bellow's Jewish heritage suggests alternate ways of being to those advocated by the enlightened thought of liberal Humanism, for example, or by one of its offshoots, Existenti'alism, or by "wasteland" ideologies. Bellow propounds certain ideas about the purpose of the novel in various articles, and these are discussed briefly in the introduction. His dismissal of the prophets of doom, those thinkers and writers who are pessimistic about the fate of humankind and the continued existence of the novel, is emphatic and certain. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

Hip to Post45

DAVID J. A L WORTH Hip to Post45 Michael Szalay, Hip Figures: A Literary History of the Democratic Party. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012. 324 pp. $24.95. here are we now?” About five years [ ] have passed since Amy Hungerford “ W asked this question in her assess- ment of the “revisionary work” that was undertaken by literary historians at the dawn of the twenty- first century.1 Juxtaposing Wendy Steiner’s contribution to The Cambridge History of American Literature (“Postmodern Fictions, 1970–1990”) with new scholarship by Rachel Adams, Mark McGurl, Deborah Nelson, and others, Hungerford aimed to demonstrate that “the period formerly known as contemporary” was being redefined and revitalized in exciting new ways by a growing number of scholars, particularly those associated with Post45 (410). Back then, Post45 named but a small “collective” of literary historians, “mainly just finishing first books or in the middle of second books” (416). Now, however, it designates something bigger and broader, a formidable institution dedi- cated to the study of American culture during the second half of the twentieth century and beyond. This institution comprises an ongoing sequence of academic conferences (including a large 1. Amy Hungerford, “On the Period Formerly Known as Contemporary,” American Literary History 20.1–2 (2008) 412. Subsequent references will appear in the text. Contemporary Literature 54, 3 0010-7484; E-ISSN 1548-9949/13/0003-0622 ᭧ 2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System ALWORTH ⋅ 623 gathering that took place at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2011), a Web-based journal of peer-reviewed scholarship and book reviews (Post45), and a monograph series published by Stanford University Press (Post•45). -

Fantasy Cartography

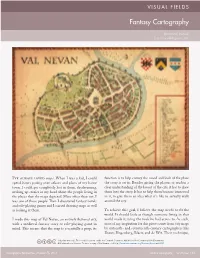

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

Postsecular Sermons in Contemporary American Fiction

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Spring 6-30-2011 The Sermonic Urge: Postsecular Sermons in Contemporary American Fiction Peter W. Rorabaugh Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rorabaugh, Peter W., "The Sermonic Urge: Postsecular Sermons in Contemporary American Fiction." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/75 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SERMONIC URGE: POSTSECULAR SERMONS IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN FICTION by PETER W. RORABAUGH Under the Direction of Christopher Kocela ABSTRACT Contemporary American novels over the last forty years have developed a unique orientation toward religious and spiritual rhetoric that can best be understood within the multidisciplinary concept of the postsecular. In the morally-tinged discourse of their characters, several esteemed American novelists (John Updike, Toni Morrison, Louise Erdrich, and Cormac McCarthy) since 1970 have used sermons or sermon-like artifacts to convey postsecular attitudes and motivations. These postsecular sermons express systems of belief that are hybrid, exploratory, and confessional in nature. Through rhetorical analysis of sermons in four contemporary American novels, this dissertation explores the performance of postsecularity in literature and defines the contribution of those tendancies to the field of literary and rhetorical studies. INDEX WORDS: Postsecular, Postmodern, Christianity, American literature, Sermon, Religious rhetoric, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, Louise Erdrich, John Updike, Cormac McCarthy, Kenneth Burke, St. -

Chinese Scholars' Perspective on John Updike's "Rabbit Tetralogy"1

Linguistics and Literature Studies 8(1): 8-13, 2020 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2020.080102 Chinese Scholars' Perspective on John Updike's 1 "Rabbit Tetralogy" Zhao Cheng Foreign Languages Studies School, Soochow University, China Received Ocotber 15, 2019; Revised November 25, 2019; Accepted December 4, 2019 Copyright©2020 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Updike's masterpiece, using skillful realism, most productive, and most awarded writers in the United succeeded in drawing a panoramic picture of the American States in the second half of the twentieth century. "Rabbit society from the 1950s to the early 1990s in the "Rabbit Tetralogy", Updike’s masterpiece, the core of the entire Tetralogy." Updike strives to reflect the changes in literary creation system of Updike, composed of "Rabbit contemporary American social culture for nearly half a Run" (1960), "Rabbit Redux" (1971), "Rabbit is Rich" century from the "rabbit" Harry, the everyman of the (1981), and "Rabbit at Rest" (1991), represents the highest American society and the life experiences of his ordinary achievement of the writer’s novel creation. In famil y. "Rabbit Tetralogy" truly reflects the living contemporary American literature, the publication of conditions of the contradictions of contemporary Rabbit Tetralogy is considered as a landmark event, and Americans: endless pursuit of free life or independent self Updike’s character "Rabbit" Harry, one of the "most and the embarrassment and helplessness of it; the confusing literary figures in traditional American customary life and hedonism under the traditional values, literature", has become a classic figure in contemporary the intense collision of self-indulgent lifestyles inspired by American literature. -

THE QUEST OP the HERO in the NOVELS OP SAUL BELLOW By

THE QUEST OP THE HERO IN THE NOVELS OP SAUL BELLOW by BETTY JANE TAAPPE, B.A. A THESIS IN ENGLISH Submltted to the Graduate Paculty of Texas Technologlcal College In Partial Pulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OP ARTS 4e T3 I9CL /\/o. m Cop. Z ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am <Jeeply lndebte<J to Professor Mary Sue Carlock for her dlrectlon of this thesls. 11 CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGpENT. 11 INTRODUCTÍON 7 . 1 Chapter I. PAILURE IN ISOLATION . 6 II. EXPERIENCE AS A TEST POR EXISTENCE. 25 III. "THE TRUTH COMES IN BLOWS". .... 5k IV. STATEMENT OP EXTERNAL EXPERIENCE AND INTELLECTUALITY 78 CONCLUSION 100 iii INTRODUCTION Many novels of the past few decades have been characterized by theraes which eraphasize human freedom, rebellion, fatalism, mechanical necessity, and obsession, and because of the tendency of the "raodern hero" to vacil- late in a somewhat precarious way between the prevalent themes of Promethean defiance and Sisyphean despair, there seems to have developed a pattern in modern literature, ironic and paradoxical, that involves the hero in a struggle for identity in a world that almost always is rejected by him as incoraprehensible or absurd. Because of the omnivorous nature of the novel as a literary form, both the intellectual therae of defiance and the raetaphysical "anguish" are presented not only in sophisticated, cosraopolitian, intellectual set- tings, but also in provincial atraospheres, where daily rou- tines, sounds, and sraells are very familiar. Therefore, the raodern novel or, as Howe prefers, the "post-raodem" novel, in raany ways serves as a docuraent on raan and his attempt to elicit meaning frora a world that alraost always proves to be irremediably absurd. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

The Representation of Jewish Americanness and Identity in Saul Bellow’S the Victim, Seize the Day, and Herzog

T.C. BAŞKENT ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ AMERİKAN KÜLTÜRÜ VE EDEBİYATI ANABİLİM DALI TEZLİ YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI Bellow’s Assimilated Protagonists: The Representation of Jewish Americanness and Identity in Saul Bellow’s The Victim, Seize the Day, and Herzog YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ HAZIRLAYAN İNANÇ PİRİMOĞLU TEZ DANIŞMANI Assist. Prof. Dr. DEFNE TUTAN ANKARA - 2017 T.C. BAŞKENT ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ AMERİKAN KÜLTÜRÜ VE EDEBİYATI ANABİLİM DALI TEZLİ YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI Bellow’un Assimile Olmuş Ana Karakterleri: Saul Bellow’un The Victim, Seize the Day ve Herzog eserlerinde Amerikan Yahudiliği ve Kimliği Temsili YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ HAZIRLAYAN İNANÇ PİRİMOĞLU TEZ DANIŞMANI Yrd. Doç. Dr. DEFNE TUTAN ANKARA –2017 Republic of Turkey Başkent University Institute of Social Sciences We certify that we have read this thesis and that in our combined opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in American Culture and Literature. Assist. Prof. Dr. Defne Tutan (Başkent University) (Advisor) Prof. Dr. Himmet Umunç (Başkent University) (Committee Member ) Assist. Prof. Dr. Ayça Germen (Hacettepe University) (Committee Member) Approved for the Institute of Social Sciences 28.02.2017 Prof. Dr. Doğan Tuncer ABSTRACT Jewish-Americanness is an overwhelming and recurrent theme in Saul Bellow’s fiction. Three of his novels — The Victim (1947), Seize the Day (1956), and Herzog (1964) — affirm the author’s sustained interest in placing the stories of the protagonists within the context of their social and cultural in-betweenness. Asa Leventhal in The Victim, Tommy Wilhelm in Seize the Day, and Herzog in Herzog lack father figures, and they internalize American culture as they accept it as the moral authority. -

Robert A. Wilson Collection Related to James Purdy

Special Collections Department Robert A. Wilson Collection related to James Purdy 1956 - 1998 Manuscript Collection Number: 369 Accessioned: Purchase and gifts, April 1998-2009 Extent: .8 linear feet Content: Letters, cards, photographs, typescripts, galleys, reviews, newspaper clippings, publishers' announcements, publicity and ephemera Access: The collection is open for research. Processed: June 1998, by Meghan J. Fuller for reference assistance email Special Collections or contact: Special Collections, University of Delaware Library Newark, Delaware 19717-5267 (302) 831-2229 Table of Contents Biographical Notes Scope and Contents Note Series Outline Contents List Biographical Notes James Purdy Born in Ohio on July 17, 1923, James Purdy is one of the United States' most prolific, yet little known writers. A novelist, poet, playwright and amateur artist, Purdy has published over fifty volumes. He received his education at the University of Chicago and the University of Peubla in Mexico. In addition to writing, Purdy also has served as an interpreter in Latin America, France, and Spain, and spent a year lecturing in Europe with the United States Information Agency (1982). From the outset of his writing career, Purdy has had difficulties attracting the attention of both publishers and critics. His first several short stories were rejected by every magazine to which he sent them, and he was forced to sign with a private publisher for his first two books, 63: Dream Palace and Don't Call Me by My Right Name and Other Stories, both published in 1956. Hoping to increase his readership, Purdy sent copies of these first two books to writers he admired, including English poet Dame Edith Sitwell. -

The Teacher and American Literature. Papers Presented at the 1964 Convention of the National Council of Teachers of English

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 042 741 TB 001 605 AUTHOR Leary, Lewis, Fd. TITLE The Teacher and American Literature. Papers Presented at the 1964 Convention of the National Council of Teachers of English. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Champaign, Ill. PUB DATE 65 NOTE 194p. EDITS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC-$9.80 DESCRIPTORS American Culture, *American Literature, Authors, Biographies, Childrens Books, Elementary School Curriculum, Literary Analysis, *Literary Criticism, *Literature Programs, Novels, Poetry, Short Stories ABSTRACT Eighteen papers on recent scholarship and its implications for school programs treat American ideas, novels, short stories, poetry, Emerson and Thoreau, Hawthorne and Melville, Whitman and Dickinson, Twain and Henry James, and Faulkner and Hemingway. Authors are Edwin H. Cady, Edward J. Gordon, William Peden, Paul H. Krueger, Bernard Duffey, John A. Myers, Jr., Theodore Hornberger, J. N. Hook, Walter Harding, Betty Harrelson Porter, Arlin Turner, Robert E. Shafer, Edmund Reiss, Sister M. Judine, Howard W.Webb, Jr., Frank H. Townsend, Richard P. Adams, and John N. Terrey. In five additional papers, Willard Thorp and Alfred H. Grommon discuss the relationship of the teacher and curriculum to new.a7proaches in American literature, while Dora V. Smith, Ruth A. French, and Charlemae Rollins deal with the implications of American literature for elementary school programs and for children's reading. (MF) U.S. DEPAIIMENT Of NE11114. EDUCATION A WOK Off ICE Of EDUCATION r--1 THIS DOCUMENT HAS KM ITEPtODUCIO EXACTLY AS IHCEIVID 1110D1 THE 11115011 01 014111I1.1101 01,611111116 IL POINTS Of TIM PI OPINIONS 4" SIAM 00 NOT IKESSAIllY INPINSENT OFFICIAL OW Of IDS/CATION N. -

Derek Jarman Sebastiane

©Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. Pre-Publication Web Posting 191 DEREK JARMAN SEBASTIANE Derek Jarman, the British painter and set designer and filmmaker and diarist, said about the Titanic 1970s, before the iceberg of AIDS: “It’s no wonder that a generation in reaction [to homopho- bia before Stonewall] should generate an orgy [the 1970s] which came as an antidote to repression.” Derek knew decadence. And its cause. He was a gay saint rightly canonized, literally, by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. As editor of Drummer, I featured his work to honor his talent. If only, like his rival Robert Mapplethorpe, he had shot a Drummer cover as did director Fred Halsted whose S&M films LA Plays Itself and Sex Garage are in the Museum of Modern Art. One problem: in the 1970s, England was farther away than it is now, and Drummer was lucky to get five photographs from Sebastiane. On May 1, 1969, I had flown to London on a prop-jet that had three seats on each side of its one aisle. A week later the first jumbo jet rolled out at LAX. That spring, all of Europe was reel- ing still from the student rebellions of the Prague Summer of 1968. London was Carnaby Street, The Beatles, and on May 16, the fabulous Brit gangsters the Kray twins—one of whom was gay—were sentenced. London was wild. I was a sex tourist who spent my first night in London on the back of leatherman John Howe’s motorcycle, flying past Big Ben as midnight chimed.