The Novel Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

SPACE RESEARCH in POLAND Report to COMMITTEE

SPACE RESEARCH IN POLAND Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) 2020 Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) ISBN 978-83-89439-04-8 First edition © Copyright by Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Warsaw, 2020 Editor: Iwona Stanisławska, Aneta Popowska Report to COSPAR 2020 1 SATELLITE GEODESY Space Research in Poland 3 1. SATELLITE GEODESY Compiled by Mariusz Figurski, Grzegorz Nykiel, Paweł Wielgosz, and Anna Krypiak-Gregorczyk Introduction This part of the Polish National Report concerns research on Satellite Geodesy performed in Poland from 2018 to 2020. The activity of the Polish institutions in the field of satellite geodesy and navigation are focused on the several main fields: • global and regional GPS and SLR measurements in the frame of International GNSS Service (IGS), International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS), International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), European Reference Frame Permanent Network (EPN), • Polish geodetic permanent network – ASG-EUPOS, • modeling of ionosphere and troposphere, • practical utilization of satellite methods in local geodetic applications, • geodynamic study, • metrological control of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) equipment, • use of gravimetric satellite missions, • application of GNSS in overland, maritime and air navigation, • multi-GNSS application in geodetic studies. Report -

Image – Action – Space

Image – Action – Space IMAGE – ACTION – SPACE SITUATING THE SCREEN IN VISUAL PRACTICE Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner (Eds.) This publication was made possible by the Image Knowledge Gestaltung. An Interdisciplinary Laboratory Cluster of Excellence at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (EXC 1027/1) with financial support from the German Research Foundation as part of the Excellence Initiative. The editors like to thank Sarah Scheidmantel, Paul Schulmeister, Lisa Weber as well as Jacob Watson, Roisin Cronin and Stefan Ernsting (Translabor GbR) for their help in editing and proofreading the texts. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No-Derivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Copyrights for figures have been acknowledged according to best knowledge and ability. In case of legal claims please contact the editors. ISBN 978-3-11-046366-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-046497-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-046377-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956404 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche National bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com, https://www.doabooks.org and https://www.oapen.org. Cover illustration: Malte Euler Typesetting and design: Andreas Eberlein, aromaBerlin Printing and binding: Beltz Bad Langensalza GmbH, Bad Langensalza Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Inhalt 7 Editorial 115 Nina Franz and Moritz Queisner Image – Action – Space. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Ariadne and Dionysus

Ariadne and Dionysus. Foreword. The Greek legends, as we know them from Homer, Hesiod, and other ancient sources, have their origins in the Bronze Age about the time of the thirteenth century B.C., which is when many scholars think something resembling the Trojan War may have taken place. The biblical Abraham may be of the same period. It was a time when the concept of Earth as the great Mother-Goddess, immanent in all things as all things were in Her, was being replaced throughout the region by the idea of an external Sky God, probably introduced by the marauding nom- adic tribes coming down from the north. At the same time, and for the same reasons, the principle of matriarchy was being replaced by patriarchy. The transformation was slow and spor- adic but eventually complete, at least on the surface. The legends, repeated by story-tellers for centuries before they were written down, probably with many deviations from the original, were meant to be pleasing to men. It has been my object to imagine the same events from the point of view of the women concerned. To this end I have added "fictional" material of my own. The more familiar version of the story of Ariadne and Dionysus is that she married him after being abandoned by Theseus. Dionysus was either man or god, as with many of the old myth- ical characters. I have imagined that she gave birth to him. Some may complain of the way I tell it, but after so long a time, who knows? In all the legends there are different known versions. -

Annotated Books Received

ANNOTATED BOOKS RECEIVED A SUPPLEMENT OF TRANSLATION REVIEW Volume 9, No. 2 December 2003 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS ANNOTATED BOOKS RECEIVED All correspondence and inquiries should be directed to Translation Review The University of Texas at Dallas Box 830688 - JO51 Richardson, TX 75083-0688 Telephone: (972) 883-2092 or 883-2093 Fax: (972) 883-6303, e-mail: [email protected] Annotated Books Received, published twice a year, is a Supplement of Translation Review, a joint publication of the American Literary Translators Association and the Center for Translation Studies at The University of Texas at Dallas. ISSN 0737-4836 Copyright © 2003 by Translation Review. The University of Texas at Dallas is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer. ANNOTATED BOOKS RECEIVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Arabic...................................................................................................................................1 Bosnian ................................................................................................................................1 Bulgarian..............................................................................................................................1 Catalan .................................................................................................................................1 Chinese.................................................................................................................................1 Dutch....................................................................................................................................4 -

Tolstoy and Zola: Trains and Missed Connections

Tolstoy and Zola: Trains and Missed Connections Nina Lee Bond Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Nina Lee Bond All rights reserved ABSTRACT Tolstoy and Zola: Trains and Missed Connections Nina Lee Bond ŖTolstoy and Zolaŗ juxtaposes the two writers to examine the evolution of the novel during the late nineteenth century. The juxtaposition is justified by the literary critical debates that were taking place in Russian and French journals during the 1870s and 1880s, concerning Tolstoy and Zola. In both France and Russia, heated arguments arose over the future of realism, and opposing factions held up either Tolstoyřs brand of realism or Zolařs naturalism as more promising. This dissertation uses the differences between Tolstoy and Zola to make more prominent a commonality in their respective novels Anna Karenina (1877) and La Bête humaine (1890): the railways. But rather than interpret the railways in these two novels as a symbol of modernity or as an engine for narrative, I concentrate on one particular aspect of the railway experience, known as motion parallax, which is a depth cue that enables a person to detect depth while in motion. Stationary objects close to a travelling train appear to be moving faster than objects in the distance, such as a mountain range, and moreover they appear to be moving backward. By examining motion parallax in both novels, as well as in some of Tolstoyřs other works, The Kreutzer Sonata (1889) and The Death of Ivan Il'ich (1886), this dissertation attempts to address an intriguing question: what, if any, is the relationship between the advent of trains and the evolution of the novel during the late nineteenth century? Motion parallax triggers in a traveler the sensation of going backward even though one is travelling forward. -

Cover No Spine

2006 VOL 44, NO. 4 Special Issue: The Hans Christian Andersen Awards 2006 The Journal of IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People Editors: Valerie Coghlan and Siobhán Parkinson Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Church of Ireland College of Education, Dublin, Ireland. Editorial Review Board: Sandra Beckett (Canada), Nina Christensen (Denmark), Penni Cotton (UK), Hans-Heino Ewers (Germany), Jeffrey Garrett (USA), Elwyn Jenkins (South Africa),Ariko Kawabata (Japan), Kerry Mallan (Australia), Maria Nikolajeva (Sweden), Jean Perrot (France), Kimberley Reynolds (UK), Mary Shine Thompson (Ireland), Victor Watson (UK), Jochen Weber (Germany) Board of Bookbird, Inc.: Joan Glazer (USA), President; Ellis Vance (USA),Treasurer;Alida Cutts (USA), Secretary;Ann Lazim (UK); Elda Nogueira (Brazil) Cover image:The cover illustration is from Frau Meier, Die Amsel by Wolf Erlbruch, published by Peter Hammer Verlag,Wuppertal 1995 (see page 11) Production: Design and layout by Oldtown Design, Dublin ([email protected]) Proofread by Antoinette Walker Printed in Canada by Transcontinental Bookbird:A Journal of International Children’s Literature (ISSN 0006-7377) is a refereed journal published quarterly by IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People, Nonnenweg 12 Postfach, CH-4003 Basel, Switzerland tel. +4161 272 29 17 fax: +4161 272 27 57 email: [email protected] <www.ibby.org>. Copyright © 2006 by Bookbird, Inc., an Indiana not-for-profit corporation. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Items from Focus IBBY may be reprinted freely to disseminate the work of IBBY. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

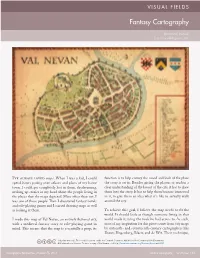

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ POCHÉ PARISIENNE: THE INTERIOR URBANITY OF NINETEENTH CENTURY PARIS A Thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Department of Architecture of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2001 by Sudipto Ghosh Dip. Arch (B. Arch), C.E.P.T, Ahmedabad, India, 1997 Committee Chair: John E. Hancock Poché Parisienne: The Interior Urbanity of Nineteenth Century Paris ABSTRACT The “Haussmannization” of Paris was characterized as much by what it ‘defined’, as by what it excluded. The thesis focuses on the apartment houses, the brothels, and the sewers as embodiments of those exclusions that were part of the process of Paris’s modernization between 1852 and 1870. By analyzing the representations of these spaces in architectural drawings, photographs and the literary novel, the paper posits that poché, an architectural drawing technique of defining and excluding, was implicitly a part of that process. For Haussmann and Napoleon III, the image of progress was built upon the elimination of all that could not be observed, decoded, or homogenized. In attacking the hidden pockets of private spaces of the apartment houses of the lower classes, the brothels, sewers and catacombs as disorderly, unhygienic and immoral, the State promoted notions of progress as scientific, hygienic and moral.