Mimesis, Romance, Novel: Representation of Milieu in the Monk and Nostromo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fictionality

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Edited by Franco Moretti: The Novel, Volume 1 is published by Princeton University Press and copyrighted, © 2006, by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any network servers. Follow links for Class Use and other Permissions. For more information send email to: [email protected] CATHERINE GALLAGHER The Rise of Fictionality No feature of the novel seems to be more obvious and yet more easily ig nored than its fictionality. Like prose, fictional is one of those definitive terms (“a novel is a long, fictional prose narrative”) that most historians of the form have tacitly agreed to leave unexamined; we tend to let it lie dormant in our critical analyses as well. And yet we all know that it is active and de termining in our culture, for we cannot walk into a bookstore or read the Sunday papers without noticing that the primary categorical division in our textual universe is between “fiction” and “nonfiction.” Perhaps we imagine that a distinction so pervasive and secure can get along without our help, that it would be redundant to define such a self-evident trait. Or, perhaps we find that the theories of fictionality debated by philosophers and narratolo gists finally tell us too little about either the history or the specific properties of the novel to repay the difficulty of mastering them. -

A Natural History of the Romance Novel

A romance novel is a work ofprosefiction that tells the story of the courtship and betrothal ofone or more heroines. As this definition is neither widely known nor accepted, it ' -requires no little defense as well as some teasing out of dis- tinctions between the term put forward here, "romance novel," and terms in widespread use, such as .''E'&&nq~and "novel." I begin with the broadest term, "roman$< . ' The term "romance" is confusing~~iiiclp~~,meaning one ' .* - thing in r suncy- of me&eval lit entire& &&cc, in a cbntmhporary store for r copy of the h&mt Dartbur axit$:& &k will take you m the 'literacure" $t&on: a glance a; prdksintroduction will inform you that Malory's prose a~$$t,~4:f King Arthur is called a "romance." Ask for a roman<L d$he clerk will take t y. '%- you to the (generally) large section G& & &e stocked with Harlequins, Silhouettes and single-title releases by writers such as Nora Roberts, Amanda Quick, and Janet Dailey. Can Mal- 07's Mortc Dartbur and Quick's Dcctptwn both be romances? , They can be and are, but only Dcctption is also a romance novel . as I am defining the term here. Robert Ellrich hazards a definition of the old, encompassing term "romance": "the story of iridividual human beings pursu- :.hg their precarious existence with+ the circumscription of ~d,moral, and various other hs-worldly problems. the ce . means to show the &r what steps must be taken to reach a desired goal, sqresented often though not m the guise of a spouse" @f4-75). -

Con-Scripting the Masses: False Documents and Historical Revisionism in the Americas

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2011 Con-Scripting the Masses: False Documents and Historical Revisionism in the Americas Frans Weiser University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Weiser, Frans, "Con-Scripting the Masses: False Documents and Historical Revisionism in the Americas" (2011). Open Access Dissertations. 347. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/347 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CON-SCRIPTING THE MASSES: FALSE DOCUMENTS AND HISTORICAL REVISIONISM IN THE AMERICAS A Dissertation Presented by FRANS-STEPHEN WEISER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2011 Program of Comparative Literature © Copyright 2011 by Frans-Stephen Weiser All Rights Reserved CON-SCRIPTING THE MASSES: FALSE DOCUMENTS AND HISTORICAL REVISIONISM IN THE AMERICAS A Dissertation Presented by FRANS-STEPHEN WEISER Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________________ David Lenson, Chair _______________________________________________ -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

Afrindian Fictions

Afrindian Fictions Diaspora, Race, and National Desire in South Africa Pallavi Rastogi T H E O H I O S TAT E U N I V E R S I T Y P R E ss C O L U MB us Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rastogi, Pallavi. Afrindian fictions : diaspora, race, and national desire in South Africa / Pallavi Rastogi. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-0319-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-0319-1 (alk. paper) 1. South African fiction (English)—21st century—History and criticism. 2. South African fiction (English)—20th century—History and criticism. 3. South African fic- tion (English)—East Indian authors—History and criticism. 4. East Indians—Foreign countries—Intellectual life. 5. East Indian diaspora in literature. 6. Identity (Psychol- ogy) in literature. 7. Group identity in literature. I. Title. PR9358.2.I54R37 2008 823'.91409352991411—dc22 2008006183 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–08142–0319–4) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–08142–9099–6) Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Typeset in Adobe Fairfield by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction Are Indians Africans Too, or: When Does a Subcontinental Become a Citizen? 1 Chapter 1 Indians in Short: Collectivity -

Fantasy Cartography

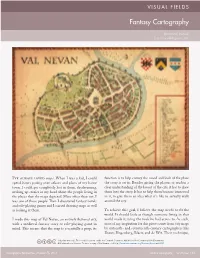

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

The Marriage of Mimesis and Diegesis in "White Teeth"

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 2019 Award Winners - Hulsman Undergraduate Jim & Mary Lois Hulsman Undergraduate Library Library Research Award Research Award Spring 2019 The aM rriage of Mimesis and Diegesis in "White Teeth" Brittany R. Raymond University of New Mexico, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ugresearchaward_2019 Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Raymond, Brittany R.. "The aM rriage of Mimesis and Diegesis in "White Teeth"." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ ugresearchaward_2019/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jim & Mary Lois Hulsman Undergraduate Library Research Award at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2019 Award Winners - Hulsman Undergraduate Library Research Award by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Raymond 1 Brittany Raymond Professor Woodward ENGL 250 28 April 2018 The Marriage of Mimesis and Diegesis in White Teeth Zadie Smith’s literary masterpiece, White Teeth, employs a yin-yang relationship between Mimesis and Diegesis, shifting the style of narration as Smith skillfully maneuvers between the past and present. As the novel is unfolding, two distinctive writing styles complement each other; we are given both brief summaries and long play-by-play descriptions of the plot, depending on the scene. Especially as the story reaches its climax with Irie, Magid and Millat, Smith begins to interchange the styles more frequently, weaving them together in the same scenes. These two literary styles are grounded in Structuralist theory, which focuses on the function of the language itself. -

Mathm 1431546286.Pdf

Abstract Tellings is an art exhibition that interprets the impermanent state of storytelling through visual art, narrative, space, and objects. Exhibited in the Stamps School of At & Design’s Slusser Gallery, this MFA thesis project places the viewer in the delicate position between the world of things and the imagined spaces of folklore and fables. Sculptures, installations, and narratives draw on folklore, mythologies and personal memories, to obscure the role of storyteller and leave the audience to build their own narratives. The work deconstructs the narratives/fables into key moments, translating them into viewer experiences in visual storytelling. This MFA thesis explores the relationships of these elements and will illuminate their role in conjuring the exhibition, Tellings. Keywords Folklore, memory, mythology, narrative, nostalgia, objects, storytelling ! 2! ! 3! Contents The Story Is: The Structure of Story and Space The Rock Is a Rock, The Book is Being a Book: Material Power Building an Island: Access Through Space Painting Around the Holes: Narrative Transformation Conclusion Exhibition Index Bibliography ! 4! The Story Is: The Structure of Story and Space Story is more than a narrative. Within this document and within my work I use the term story often. To begin with clarity I attempt to use them as the following. Narrative is the tale: a collection of characters, setting and details sewn together within a plot. They are the written fables that pair each installation. Story is greater. Story includes the narrative, but also the visceral reactions to those narratives, the collective conjuring of imagined realities, and the emotional ties to personal experience and memory. -

Nostromo a Tale of the Seaboard

NOSTROMO A TALE OF THE SEABOARD By Joseph Conrad "So foul a sky clears not without a storm." —SHAKESPEARE TO JOHN GALSWORTHY Prepared and Published by: Ebd E-BooksDirectory.com AUTHOR'S NOTE "Nostromo" is the most anxiously meditated of the longer novels which belong to the period following upon the publication of the "Typhoon" volume of short stories. I don't mean to say that I became then conscious of any impending change in my mentality and in my attitude towards the tasks of my writing life. And perhaps there was never any change, except in that mysterious, extraneous thing which has nothing to do with the theories of art; a subtle change in the nature of the inspiration; a phenomenon for which I can not in any way be held responsible. What, however, did cause me some concern was that after finishing the last story of the "Typhoon" volume it seemed somehow that there was nothing more in the world to write about. This so strangely negative but disturbing mood lasted some little time; and then, as with many of my longer stories, the first hint for "Nostromo" came to me in the shape of a vagrant anecdote completely destitute of valuable details. As a matter of fact in 1875 or '6, when very young, in the West Indies or rather in the Gulf of Mexico, for my contacts with land were short, few, and fleeting, I heard the story of some man who was supposed to have stolen single-handed a whole lighter-full of silver, somewhere on the Tierra Firme seaboard during the troubles of a revolution. -

Core Collections in Genre Studies Romance Fiction

the alert collector Neal Wyatt, Editor Building genre collections is a central concern of public li- brary collection development efforts. Even for college and Core Collections university libraries, where it is not a major focus, a solid core collection makes a welcome addition for students needing a break from their course load and supports a range of aca- in Genre Studies demic interests. Given the widespread popularity of genre books, understanding the basics of a given genre is a great skill for all types of librarians to have. Romance Fiction 101 It was, therefore, an important and groundbreaking event when the RUSA Collection Development and Evaluation Section (CODES) voted to create a new juried list highlight- ing the best in genre literature. The Reading List, as the new list will be called, honors the single best title in eight genre categories: romance, mystery, science fiction, fantasy, horror, historical fiction, women’s fiction, and the adrenaline genre group consisting of thriller, suspense, and adventure. To celebrate this new list and explore the wealth of genre literature, The Alert Collector will launch an ongoing, occa- Neal Wyatt and Georgine sional series of genre-themed articles. This column explores olson, kristin Ramsdell, Joyce the romance genre in all its many incarnations. Saricks, and Lynne Welch, Five librarians gathered together to write this column Guest Columnists and share their knowledge and love of the genre. Each was asked to write an introduction to a subgenre and to select five books that highlight the features of that subgenre. The result Correspondence concerning the is an enlightening, entertaining guide to building a core col- column should be addressed to Neal lection in the genre area that accounts for almost half of all Wyatt, Collection Management paperbacks sold each year.1 Manager, Chesterfield County Public Georgine Olson, who wrote the historical romance sec- Library, 9501 Lori Rd., Chesterfield, VA tion, has been reading historical romance even longer than 23832; [email protected]. -

Rethinking Mimesis

Rethinking Mimesis Rethinking Mimesis: Concepts and Practices of Literary Representation Edited by Saija Isomaa, Sari Kivistö, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Sanna Nyqvist, Merja Polvinen and Riikka Rossi Rethinking Mimesis: Concepts and Practices of Literary Representation, Edited by Saija Isomaa, Sari Kivistö, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Sanna Nyqvist, Merja Polvinen and Riikka Rossi Layout: Jari Käkelä This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Saija Isomaa, Sari Kivistö, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Sanna Nyqvist, Merja Polvinen and Riikka Rossi and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3901-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3901-3 Table of ConTenTs Introduction: Rethinking Mimesis The Editors...........................................................................................vii I Concepts of Mimesis Aristotelian Mimesis between Theory and Practice Stephen Halliwell....................................................................................3 Rethinking Aristotle’s poiêtikê technê Humberto Brito.....................................................................................25 Paul Ricœur and -

Apocalypse Now

Sabrina Baiguera Università degli Studi di Bergamo Letteratura Anglo-americana LMI A.A. 2011/2012 Paolo Jachia’s Francis Ford Coppola: Apocalypse Now. Un’analisi semiotica , an intertextual reconstruction of the texts, of the cultural references that lie behind the film. Apocalypse Now (1979) Two versions: the orginal version (1979) and the extended version ( Apocalypse Now Redux: 2001 ), released in 2001. The film is set during the Vietnam war (the action takes place approximately in 1970) It tells the story of U.S. Army Captain Benjamin L. Willard who has the mission to proceed up the Nung river into Cambodia, find Colonel Kurtz and “terminate” his command, by whatever means available. Willard starts a journey up the Nung river on a PBR (Petrol Boat) with a four- man crew (Chef – a saucier; Chief – the chief of the boat; Clean – a 17 year- old young from Bronx; Lance – a professional surfer). Kurtz had deserted the U.S. Army to start his own private war in the middle of the jungle. There he is worshipped as a god by his own Montagnard army, but he has gone insane and his methods are “unsound”. The artistic dimension Source texts of Apocalypse Now : 1. Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1899) 2. James G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890) 3. Jessie Weston’s From ritual to romance (1920) 4. Goethe’s Faust (1808) 5. The Holy Bible 6. T.S.Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922) and The Hollow Men (1925) 7. Baudelaire’s The Albatross (1861) 8. The Doors’ The End Heart of Darkness (1899) “In the case of “Apocalypse,” there was a script written by the great John Milius, but, I must say, what I really made the film from was the little green copy of Heart of Darkness that I had done all those lines in.” (Coppola) Heart of Darkness was not credited as a source text when the film first came out.