Uncovering and Recovering the Popular Romance Novel A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond the Bodice Ripper: Innovation and Change in The

© 2014 Andrea Cipriano Barra ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BEYOND THE BODICE RIPPER: INNOVATION AND CHANGE IN THE ROMANCE NOVEL INDUSTRY by ANDREA CIPRIANO BARRA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School—New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Sociology Written under the direction of Karen A. Cerulo And approved by _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey OCTOBER 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Beyond the Bodice Ripper: Innovation and Change in the Romance Novel Industry By ANDREA CIPRIANO BARRA Dissertation Director: Karen A. Cerulo Romance novels have changed significantly since they first entered the public consciousness. Instead of seeking to understand the changes that have occurred in the industry, in readership, in authorship, and in the romance novel product itself, both academic and popular perception has remained firmly in the early 1980s when many of the surface criticisms were still valid."Using Wendy Griswold’s (2004) idea of a cultural diamond, I analyze the multiple and sometimes overlapping relationships within broader trends in the romance industry based on content analysis and interviews with romance readers and authors. Three major issues emerge from this study. First, content of romance novels sampled from the past fourteen years is more reflective of contemporary ideas of love, sex, and relationships. Second, romance has been a leader and innovator in the trend of electronic publishing, with major independent presses adding to the proliferation of subgenres and pushing the boundaries of what is considered romance. Finally, readers have a complicated relationship with the act of reading romance and what the books mean in their lives. -

Second Night of 2020 Creative Arts Emmy® Winners Announced

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SECOND NIGHT OF 2020 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® WINNERS ANNOUNCED (LOS ANGELES – Sept. 15, 2020) — The Television Academy tonight hosted the second of its five 2020 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies honoring outstanding artistic and technical achievement in television at Emmys.com. The ceremony awarded many talented artists and craftspeople in the categories of Variety Programming. The ceremony was hosted by Emmy-nominated host Nicole Byer and featured presenters from some of the season’s most popular shows including Josh Flagg (Million Dollar Listing Los Angeles), Chris Hardwick (The Wall; The Talking Dead), Sofia Hublitz (Ozark), Thomas Lennon (Reno 911), Desus Nice & The Kid Mero (Desus & Mero), Jeremy Pope (Hollywood), Issa Rae (A Black Lady Sketch Show; Insecure) and Tracy Tutor (Million Dollar Listing Los Angeles). The 2020 Creative Arts Emmy Awards are being streamed on Emmys.com for four consecutive nights, Monday, Sept. 14, through Thursday, Sept. 17, at 8:00 p.m. EDT/5:00 p.m. PDT with a fifth broadcast ceremony on Saturday, Sept. 19, at 8:00 p.m. EDT/5:00 p.m. PDT on FXX. Winners' names are known only by Ernst & Young LLP until they are revealed to the director of the Emmys ceremony as the show is airing. All five shows are produced by Bob Bain Productions. # # # Press Contact: Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight (for the Television Academy) [email protected] 818-462-1150 For more information, please visit emmys.com. TELEVISION ACADEMY 2020 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 15, 2020 -

Owen Glendower and the Failure of Historical Romance

52 53 Yankee puritanism and Southern aristocracy, was evinced in American literature as early as the works of James Fenimore Cooper. More recently, revisionist historical works, such as Stephen Saunders Webb, 1676: The End of American Independence (New York: Knopf, 1984) and Francis Jennings, The Invasion of America, have The Mythology of Escape: Owen expanded on the Cooper vision of the upstate New York-native Glendower and the Failure of American connection. These works have enhanced the sense of the Historical Romance native Americans as historical actors, not just passive primitives. This is far more Powysian in spirit than a view of the Indians as noble, poetic savages, transatlantic "Celts." Ian Duncan 12 Powys's interest in this area was, as usual, clairvoyant and prophetic; it went unmatched in any visible American literary production until the recent appearance of William Least Heat Owen Glendower, so melancholy in its Moon's PriaryErth, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991). preoccupation with lost origins, was the novel of John Cowper Powys's "homecoming." In 1934, Powys imposed a deceptive narrative closure upon the first sixty years of his life in the great Autobiography, and left America, where he had written his Wessex romances, to return to Britain, eventually settling in Wales in 1936. Powys's Welsh essays, collected in Obstinate Cymric (1947), record the identification of his "philosophy up-to-date" with "the idea of Wales" as a configuration of landscape, mythology and race.l Yet Powys had never lived there; the place of -

Introduction

Abstract: This essay looks at the interconnections between the cultural industry of popular romance and best-selling novels set in an Irish historical context. In particular, it examines two best-selling novels by North American author Karen Robards, which have not yet been examined in academia: Dark of the Moon (1988) and Forbidden Love (2013; originally published in 1983). Although this small selection constitutes only a preliminary study of an expanding popular genre, it is my hope that it will serve as a relevant example of how Ireland is exoticised in the transnational cultural industry of romance. Drawing on several studies on popular romance (Radway 1984; Strehle and Carden 2009; and Roach 2016), and on specific sources devoted to the study of historical romance, in particular when set in exotic locations (Hughes 2005; Philips 2011; Teo 2012; 2016), I intend to demonstrate how these novels by Karen Robards follow the clichés and conventions of the typical romances produced in the 1980s. As I show, the popularity that Robards’ novels still enjoy reflects the supremacy of the genre and the wide reception of this kind of fiction in the global market. Keywords: Cultural industry; popular romance; Irish context; market. Introduction In her semi-academic, ethnographic study Happily-Ever-After, Catherine Roach (4) identifies romance as “the prime cultural narrative of the modern Western world”. This is a best-selling genre which dominates the publishing industry, particularly in North America and other Western European countries. It is generally a woman-centred genre, as most authors and readers are female (110). The basic plot of the (heterosexual) romance narrative revolves around a hero and a heroine, who fall in love, work through many trials and tribulations and end up happily. -

In LGBT: Gender Identity and Gender Expression Online Learning Program

BIBLIOGRAPHY This bibliography lists sources used to research Understanding the “T” in LGBT: Gender Identity and Gender Expression online learning program. Additional helpful resources are listed as well. BOOK SOURCES Bender-Baird, K. (2011). Transgender employment experiences: Gendered perceptions and the law. Albany, NY: State University of New York. Hall, D.M. (2009). Allies at work: Creating a lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender inclusive work environment. San Francisco, CA: Out & Equal Workplace Advocates. Herman, J. (2009). Transgender explained for those who are not. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. Sheridan, V. (2009). The complete guide to transgender in the workplace. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC- CLIO. Walworth, J. (1999). Working with a transsexual: A guide for coworkers. Los Angeles, CA: Center for Gender Sanity. Walworth, J. (2003). Transsexual workers: An employer’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Center for Gender Sanity. Weiss, J.T. (2007). Transgender workplace diversity: Policy tools, training issues and communication strategies for HR and legal professionals. Mahwah, NJ: Dr. Jillian T. Weiss. PUBLICATION SOURCES A blueprint for equality, a federal agenda for transgender people. (2011). National Center for Transgender Equality. Retrieved September 27, 2013, from http://www.transequality.org/Resources/NCTE_Blueprint_for_Equality2012_FINAL.pdf Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the LGBT community: A field guide. (2011). The Joint Commission. Retrieved September 27, 2013, from http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/LGBTFieldGuide_WEB_LINKED_VER.pdf Coleman, E., Bockting, et. al.. (2011). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 13, 165 – 232. Retrieved on September 27, 2013, from http://www.wpath.org/uploaded_files/140/files/IJT%20SOC,%20V7.pdf Diagram of sex and gender. -

Hollywood: Her Story February 2020 Enewsletter Oscar Wrap Up

Hollywood: Her Story February 2020 ENewsletter Oscar Wrap Up The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has announced this year’s Oscar winners! Let’s take a look at how the women fared in this 92nd year of Oscar history. Let’s celebrate the women who took home the acting Oscars. Renee Zellweger has received four acting Oscar nominations, including two Oscar wins. She received the Best Actress Oscar this year for her performance as Judy Garland in Judy. After two other acting nominations, Laura Dern received the Best Supporting Actress award this year for Marriage Story. Kwak Sin Ae shared a Best Picture Oscar for Parasite, which won for Best Picture and for Best International Feature Film. Women have been historically strong in a number of categories. In Best Costume Design, Jacqueline Durran received her seventh nomination this year and her second Oscar win for Little Women. Anne Morgan and Vivian Baker shared their first Oscar for Best Makeup and Hairstyling for Bombshell. In Best Production Design, Barbara Ling and Nancy Haigh won for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. Nancy Haigh has another Oscar win and six other nominations under her belt. It can be argued that the biggest win of the evening was in the category ofB est Original Score. Only twelve women have received nominations in this category over the years. When Hildur Guðnadóttir won the Oscar for her musical score for Joker, she became the fourth woman to win in this category. It should be noted that a woman conducted the orchestra, the first time in the history of the Oscar ceremonies, to present the musical scores for these Oscar nominees. -

Melina Root Costume Designer

MELINA ROOT COSTUME DESIGNER TELEVISION DIRECTOR STUDIO/NETWORK NO TOMORROW (Pilot) Brad Silberling CBS Television/The CW CRAZY EX-GIRLFRIEND (Pilot, Season 1) Marc Webb CBS Television/The CW STATE OF AFFAIRS (Pilot) Joe Carnahan Universal Television GUYS WITH KIDS (Pilot & Series) Scott Ellis (Pilot) Universal Television/NBC BROTHERS AND SISTERS Various Touchstone/ABC (Season 2: Episodes 13-16 & Seasons 3-5) Warner Bros./Adult Swim HITCHED (Pilot) Rob Greenberg Warner Bros./CBS th MISS GUIDED (Series/Season 1) Todd Holland (Pilot) 20 Century Fox/ABC PLAYING CHICKEN (Pilot) John Pasquin Warner Bros./FOX 20 GOOD YEARS (Pilot & Series) Terry Hughes Warner Bros./NBC NEIGHBORS (Pilot) Jeff Melman Touchstone/ABC INSEPARABLE (Pilot) Pam Fryman NBC Universal/CBS THAT 80’S SHOW (Pilot & Series) Terry Hughes Carsey-Werner/FOX THAT 70’S SHOW (Pilot & Series) David Trainer Carsey-Werner/FOX Emmy Award: Outstanding Costumes for a Series, 1999 Emmy Nominations: Outstanding Costumes for a Series, 2002-2004 Costume Designers Guild Awards Nominations, 2000-2001, 2003, 2005 RD 3 ROCK FROM THE SUN (Pilot/Series) James Burrows (Pilot), Terry Hughes Carsey-Werner/NBC 1997 Emmy Award Outstanding Costumes for a Series, “Nightmare on Dick Street” 1998 Emmy Nomination: Outstanding Costumes for a Series, “36, 24, 36 Dick” 2000 Costume Designers Guild Awards Nomination NORMAL, OHIO (Pilot & Season 1: Episodes 1-6) Philip Charles MacKenzie Carsey-Werner/NBC TOWNIES (Pilot) Pam Fryman Carsey-Werner/ABC THE MARTIN SHORT SHOW (Series/Special) John Blanchard NBC SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE (Seasons 16-19) Various NBC LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN Various NBC (Wardrobe Redesign for Hosts) FEATURES DIRECTOR STUDIO BROTHERS SOLOMON Bob Odenkirk Revolution Studios WAYNE'S WORLD II Stephen Surjik Paramount Pictures MURTHA SKOURAS AGENCY 1025 COLORADO AVENUE, SANTA MONICA, CA 90401 PHONE 310.395.4600 | FAX 310.395.4622 WWW.MURTHASKOURAS.COM . -

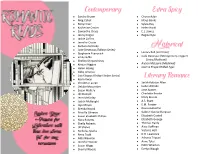

Romantic Reads

Contemporary Extra Spicy Sandra Brown Cherry Adair Meg Cabot Maya Banks Robyn Carr Sylvia Day Katherine Center Helen Hardt Samantha Chase E.L. James Jenny Colgan Regina Kyle Jackie Collins Jennifer Crusie Barbara Delinsky istorical Jude Deveraux (Edilean Series) Stephanie Evanovich Lenora Bell (Victorian) Emily Giffin Jude Deveraux (Montgomery-Taggert Shelley Shepard Gray Series/Medieval) Kristan Higgins Alyson McLayne (Medieval) Helen Hoang Joanna Shupe (Gilded Age) Abby Jimenez Lisa Kleypas (Friday Harbor Series) Literary Romance Kevin Kwan Christina Lauren Sarah Addison Allen Debbie Macomber Isabel Allende Susan Mallery Jane Austen Jill Mansell Charlotte Bronte Jenn McKinlay Emily Bronte Judith McNaught A.S. Byatt Jojo Moyes E.M. Forster Brenda Novak Diana Gabaldon Priscilla Oliveras Gabriel Garcia Marquez Susan Elizabeth Phillips Elizabeth Gaskell Nora Roberts Elizabeth George Sheila Roberts Thomas Hardy Jill Shalvis Alice Hoffman Nicholas Sparks Victoria Holt Anna Todd D.H. Lawrence Abbi Waxman Adriana Trigiani Jennifer Weiner Anne Tyler Susan Wiggs Edith Wharton Sherryl Woods Evelyn Waugh Regency Romantic Suspense Nancy Campbell Allen Sandra Brown Katharine Ashe Christina Dodd Jane Ashford Karen Harper Mary Balogh Linda Howard Lenora Bell Lisa Jackson Anna Bennett Jayne Ann Krentz Lisa Berne Kat Martin Jo Beverley Brenda Novak Kelly Bowen Erica Spindler Anna Bradley Grace Burrowes Christy Carlyle Sci-Fi, Fantasy, and Marion Chesney Tessa Dare -

53 Feature Photography by Jerry Metellus

FEATURE PHOTOGRAPHY BY JERRY METELLUS In this, Luxury's first ever “Power Influencer” issue, we present to you an impressive array of individuals who’ve been integral in enriching our community in the areas of gaming, education, arts and culture, hospitality, philanthropy and development. APRIL 2016 | LUXURYLV.COM 53 FEATURE | POWER INFLUENCER STRATEGIC THINKING PROCESS Donald Snyder’s success is a result of taking tough jobs, solving problems and building consensus BY MATT KELEMEN Donald Snyder left his position as acting president In a city where mavericks traditionally played with of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas at the end of their cards close to their chests, Snyder made it a 2015 to make way for incoming president, Len Jessup, point always to lay his on the table face up. Although but he continues to serve as presidential adviser for he arrived in Vegas with his family via Reno, Nev., as strategic initiatives. president of First Interstate Bank—which later was consolidated into Wells Fargo—his experience coming The co-founder of Bank of Nevada and prime mover into an unfamiliar situation and building consensus to behind the development of The Smith Center for the tackle tough problems worked to his benefit in the still- Performing Arts has been active with the university young city. since shortly after arriving in Las Vegas in 1987, but that initial involvement only would be the beginning of what “A lot of what I’ve done over the years I categorize would become a wide spectrum of community service more as community building,” he says, crediting his and philanthropic endeavors. -

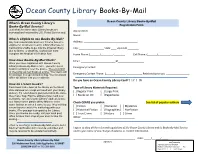

Books-By-Mail Application Form

Ocean County Library Books-By-Mail Ocean County Library Books-By-Mail What is Ocean County Library’s Registration Form Books-By-Mail Service? Just what the name says: Library books are (PLEASE PRINT) borrowed and returned by U.S. Postal Service mail. Name: _________________________________________ Who is eligible to use Books-By-Mail? Any homebound individual over 18 who has,or is Address: _______________________________________ eligible for, an Ocean County Library Borrower’s Card and is unable to get into the physical library City: __________________ State ____ Zip Code ________ due to illness or disability. A physician must complete the Medical Verification form. Home Phone: (_______)_________-________ Cell Phone: (_______)_________-________ How does Books-By-Mail Work? Email: _________________________@___________________ Once you have registered with Ocean County Library’s Books-By-Mail service, you will request Emergency Contact: ______________________________________________ books in writing or over the phone. There is a limit of checking out four books at a time. Your items will be package in a special mailer bag. Your local post Emergency Contact Phone: (______)________-___________ Relationship to you: _________________ office will deliver it to your residence. Do you have an Ocean County Library Card? [ ] Y [ ]N How do I return books? Each book is due back at the library on the latest Type of Library Materials Required: date stamped on receipt enclosed with your library [ ] Regular Print [ ] Large Print delivery. To return books, put materials in the same blue mailer bag. Flip the address index card over [ ] Books on CD [ ] Paperbacks so that the “Ocean County Library” address is face out. -

Anamcara: a Way for Marriage

ANAMCARA: A WAY FOR MARRIAGE KENNETH R. NEILSON B.A., University of Manitoba, 1978 B.S.L., Canadian Nazarene College, 1978 M.A., Eastern Nazarene College, 1994 Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry Acadia Divinity College Acadia University Spring Convocation 2016 © by KENNETH R. NEILSON 2016 This thesis by Kenneth R. Neilson was defended successfully in an oral examination on 15 March 2016. The examining committee for the thesis was: Dr. Anna Robbins, Chair Dr. Charles S. Pottie-Pâté, SJ, External Examiner Dr. John Stewart, Internal Examiner Dr. John Sumarah, Supervisor Dr. John McNally, DMin Program Director This thesis is accepted in its present form by Acadia Divinity College, the Faculty of Theology of Acadia University, as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry. ii I, Kenneth R. Neilson, hereby grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to provide copies of my thesis, upon request, on a non-profit basis. Kenneth R. Neilson Author Dr. John Sumarah Supervisor 15 March 2016 Date iii Table of Contents Abstract vii Acknowledgements viii Dedication ix Approval to Reproduce Copyright Material x Introduction 1 Description of Ministry Context 3 Statement of the Problem, Thesis Statement and Thesis Questions 3 Chapter 1 Biblical Foundation 5 A Foundation from the Gospel of John 6 The Early Christian Communities 17 A Learning Community 19 A Loving Community 20 A Worshipping Community 22 An Evangelistic Community 25 Marriage as a Witness 27 Chapter 2 Historical and Theological Perspectives and Practices of Anamcara 35 Origins of the Celtic People and their Religion 38 Celtic Religion 41 Celtic Christianity - the Influence of the Gospel 43 St. -

CONQUEST BOOK 1: Daughter of the Last King by Tracey Warr

CONQUEST BOOK 1: Daughter of the Last King By Tracey Warr 1093. The three sons of William the Conqueror – Robert Duke of Normandy, William II King of England and Count Henry – fight with each other for control of the Anglo-Norman kingdom created by their father’s conquest. Meanwhile, Nesta ferch Rhys, the daughter of the last independent Welsh king, is captured during the Norman assault of her lands. Raised with her captors, the powerful Montgommery family, Nes- ta is educated to be the wife of Arnulf of Montgommery, in spite of her pre-existing betrothal to a Welsh prince. Who will Nesta marry and can the Welsh rebels oust the Normans? Daughter of the Last King is the first in the Conquest Trilogy. Published: 1 Sept 2016 ISBN: 9781907605819 Price: £9.99 Category: Historical fiction, historical romance, medieval All marketing and publicity enquiries: [email protected] Author Bio Tracey Warr is a writer based in Wales and France, and has published novels and books on contemporary art. She was Senior Lecturer, teaching and researching on art history and theory of the 20th and 21st centuries, at Oxford Brookes Universi- ty, Bauhaus University and Dartington College of Arts. Her first novel, Almodis: The Peaceweaver (Impress, 2011), is set in 11th century France and Spain, and was shortlisted for the Impress Prize for New Fiction and the Rome Film Festival Book Initiative and received a Santander Research Award. Her second historical novel, The Viking Hostage (Impress, 2014), is set in 10th century France and Wales. She received a Literature Wales Writer’s Bursary for work on her new trilogy, Con- quest, set in 12th century Wales, England and Normandy.