Global Infatuation: Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts. the Case of Harlequin Enterprises and Sweden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond the Bodice Ripper: Innovation and Change in The

© 2014 Andrea Cipriano Barra ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BEYOND THE BODICE RIPPER: INNOVATION AND CHANGE IN THE ROMANCE NOVEL INDUSTRY by ANDREA CIPRIANO BARRA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School—New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Sociology Written under the direction of Karen A. Cerulo And approved by _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey OCTOBER 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Beyond the Bodice Ripper: Innovation and Change in the Romance Novel Industry By ANDREA CIPRIANO BARRA Dissertation Director: Karen A. Cerulo Romance novels have changed significantly since they first entered the public consciousness. Instead of seeking to understand the changes that have occurred in the industry, in readership, in authorship, and in the romance novel product itself, both academic and popular perception has remained firmly in the early 1980s when many of the surface criticisms were still valid."Using Wendy Griswold’s (2004) idea of a cultural diamond, I analyze the multiple and sometimes overlapping relationships within broader trends in the romance industry based on content analysis and interviews with romance readers and authors. Three major issues emerge from this study. First, content of romance novels sampled from the past fourteen years is more reflective of contemporary ideas of love, sex, and relationships. Second, romance has been a leader and innovator in the trend of electronic publishing, with major independent presses adding to the proliferation of subgenres and pushing the boundaries of what is considered romance. Finally, readers have a complicated relationship with the act of reading romance and what the books mean in their lives. -

Desiring the Big Bad Blade: Racing the Sheikh in Desert Romances

Desiring the Big Bad Blade: Racing the Sheikh in Desert Romances Amira Jarmakani American Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4, December 2011, pp. 895-928 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/aq.2011.0061 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/aq/summary/v063/63.4.jarmakani.html Access provided by Georgia State University (4 Sep 2013 15:38 GMT) Racing the Sheikh in Desert Romances | 895 Desiring the Big Bad Blade: Racing the Sheikh in Desert Romances Amira Jarmakani Cultural fantasy does not evade but confronts history. — Geraldine Heng, Empire of Magic: Medieval Romance and the Politics of Cultural Fantasy n a relatively small but nevertheless significant subgenre of romance nov- els,1 one may encounter a seemingly unlikely object of erotic attachment, a sheikh, sultan, or desert prince hero who almost always couples with a I 2 white western woman. In the realm of mass-market romance novels, a boom- ing industry, the sheikh-hero of any standard desert romance is but one of the many possible alpha-male heroes, and while he is certainly not the most popular alpha-male hero in the contemporary market, he maintains a niche and even has a couple of blogs and an informative Web site devoted especially to him.3 Given popular perceptions of the Middle East as a threatening and oppressive place for women, it is perhaps not surprising that the heroine in a popular desert romance, Burning Love, characterizes her sheikh thusly: “Sharif was an Arab. To him every woman was a slave, including her. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Msnll\My Documents\Voyagerreports

Swofford Popular Reading Collection September 1, 2011 Title Author Item Enum Copy #Date of Publication Call Number "B" is for burglar / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11994 PBK G737 bi "F" is for fugitive / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11990 PBK G737 fi "G" is for gumshoe / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue 11991 PBK G737 gi "H" is for homicide / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11992 PBK G737 hi "I" is for innocent / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11993 PBK G737 ii "K" is for killer / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11995 PBK G737 ki "L" is for lawless / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11996 PBK G737 li "M" is for malice / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11998 PBK G737 mi "N" is for noose / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11999 PBK G737 ni "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue 12001 PBK G737 ou 10 lb. penalty / Dick Francis. Francis, Dick. 11998 PBK F818 te 100 great fantasy short short stories / edited by Isaac 11985 PBK A832 gr Asimov, Terry Carr, and Martin H. Greenberg, with an introduction by Isaac Asimov. 1001 most useful Spanish words / Seymour Resnick. Resnick, Seymour. 11996 PBK R434 ow 1022 Evergreen Place / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12010 PBK M171 te 13th warrior : the manuscript of Ibn Fadlan relating his Crichton, Michael, 1942- 11988 PBK C928 tw experiences with the Northmen in A.D. 922. 16 Lighthouse Road / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12001 PBK M171 si 1776 / David McCullough. McCullough, David G. 12006 PBK M133 ss 1st to die / James Patterson. Patterson, James, 1947- 12002 PBK P317.1 fi 204 Rosewood Lane / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. -

Nya Talböcker Augusti 2018

Nya talböcker augusti 2018 Litteratur för vuxna .................................................................................................................... 5 Skönlitteratur ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Svenska noveller från Almqvist till Stoor .................................................................................................................... 5 Darling Mona .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Hon tackade gudarna, [thriller] .................................................................................................................................. 5 I hjärtat av hjärtat av ett annat land ........................................................................................................................... 6 Nu i ro slumra in, [en Helen Grace-deckare] .............................................................................................................. 6 Dolda spår ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Morden i Baronville, [en Amos Decker-thriller] .......................................................................................................... 6 Holländarn ................................................................................................................................................................. -

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball. -

Contributions by Employer

2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT HOME / CAMPAIGN FINANCE REPORTS AND DATA / PRESIDENTIAL REPORTS / 2008 APRIL MONTHLY / REPORT FOR C00431569 / CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT PO Box 101436 Arlington, Virginia 22210 FEC Committee ID #: C00431569 This report contains activity for a Primary Election Report type: April Monthly This Report is an Amendment Filed 05/22/2008 EMPLOYER SUM NO EMPLOYER WAS SUPPLIED 6,724,037.59 (N,P) ENERGY, INC. 800.00 (SELF) 500.00 (SELF) DOUGLASS & ASSOCI 200.00 - 175.00 1)SAN FRANCISCO PARATRAN 10.50 1-800-FLOWERS.COM 10.00 101 CASINO 187.65 115 R&P BEER 50.00 1199 NATIONAL BENEFIT FU 120.00 1199 SEIU 210.00 1199SEIU BENEFIT FUNDS 45.00 11I NETWORKS INC 500.00 11TH HOUR PRODUCTIONS, L 250.00 1291/2 JAZZ GRILLE 400.00 15 WEST REALTY ASSOCIATES 250.00 1730 CORP. 140.00 1800FLOWERS.COM 100.00 1ST FRANKLIN FINANCIAL 210.00 20 CENTURY FOX TELEVISIO 150.00 20TH CENTURY FOX 250.00 20TH CENTURY FOX FILM CO 50.00 20TH TELEVISION (FOX) 349.15 21ST CENTURY 100.00 24 SEVEN INC 500.00 24SEVEN INC 100.00 3 KIDS TICKETS INC 121.00 3 VILLAGE CENTRAL SCHOOL 250.00 3000BC 205.00 312 WEST 58TH CORP 2,000.00 321 MANAGEMENT 150.00 321 THEATRICAL MGT 100.00 http://docquery.fec.gov/pres/2008/M4/C00431569/A_EMPLOYER_C00431569.html 1/336 2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT 333 WEST END TENANTS COR 100.00 360 PICTURES 150.00 3B MANUFACTURING 70.00 3D INVESTMENTS 50.00 3D LEADERSHIP, LLC 50.00 3H TECHNOLOGY 100.00 3M 629.18 3M COMPANY 550.00 4-C (SOCIAL SERVICE AGEN 100.00 402EIGHT AVE CORP 2,500.00 47 PICTURES, INC. -

Marion Lennox & Trish Morey

Edition #197 October 2009 The official journal of Romance Writers of Australia Coffs Harbour, NSW R♥BY Winners Setting................. p4 Marion Lennox / MarionMarion LennoxLennox Trish Morey Cont... p6 Writer’s Life: Writing && TrishTrish MoreyMorey with Babies......... p8 Bronwyn Jameson chats with two of RWA’s best-loved Har- lequin authors, Marion Lennox and Trish Morey, winners of Clayton’s Conf .... p9 2009 Romantic Book of the Year (R♥BY) Awards in the Short Sweet and Short Sexy categories respectively. Our RWA: The Emerald Marion Lennox has been writing romance since she was knee Award ................. p10 high to a grasshopper, which anyone who's met Marion will real- ize was quite some time ago. She's just sold her eightieth ro- Brisbane Conference mance, but continues with the belief that she has the best job in Report ................. p11 the universe. Marion's been nominated for the R♥BY every year since its inception and is now a two-time winner. She's won the Member prestigious US RITA award twice as well. Her books are fun, Spotlight ............ p12 lighthearted celebrations of the human spirit and the power of romance to conquer all, and her latest US release more than proves that after 2 weeks as #1 Series Bestseller on the Borders/Waldenbooks list. Member News & Releases ............. p13 Trish Morey always fancied herself as a writer, so why she be- came a Chartered Accountant is anyone's guess. In 1992 she Focus on: Sagas, spied an article saying Mills&Boon was actively seeking new authors and with two young children at home, this was her UK Style.............. -

Publisher Index

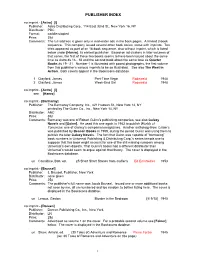

PUBLISHER INDEX no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] Publisher: Astro Distributing Corp., 114 East 32nd St., New York 16, NY Distributor: PDC Format: saddle-stapled Price: 35¢ Comments: The full address is given only in mail-order ads in the back pages. A limited 2-book sequence. This company issued several other book series, some with imprints. Ten titles appeared as part of an 18-book sequence, also without imprint, which is listed below under [Hanro], its earliest publisher. Based on ad clusters in later volumes of that series, the first of these two books seems to have been issued about the same time as Astro #s 16 - 18 and the second book about the same time as Quarter Books #s 19 - 21. Number 1 is illustrated with posed photographs, the first volume from this publisher’s various imprints to be so illustrated. See also The West in Action. Both covers appear in the Bookscans database. 1 Clayford, James Part-Time Virgin Rodewald 1948 2 Clayford, James W eek -End Girl Rodewald 1948 no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] see [Hanro] no imprint - [Barmaray] Publisher: The Barmaray Company, Inc., 421 Hudson St., New York 14, NY printed by The Guinn Co., Inc., New York 14, NY Distributor: ANC Price: 35¢ Comments: Barmaray was one of Robert Guinn’s publishing companies; see also Galaxy Novels and [Guinn]. He used this one again in 1963 to publish Worlds of Tomorrow, one of Galaxy’s companion magazines. Another anthology from Collier’ s was published by Beacon Books in 1959, during the period Guinn was using them to publish the later Galaxy Novels. -

Care Needs of Women: Tending His Flock

#110: Care Needs of Women: Tending His Flock Recommended by the Writer: Abuse 1. Allender, Dr. Dan B. The Wounded Heart: Hope for Adult victims of Childhood Sexual Abuse . Colorado Springs: NavPress,1995, 2. Evans, Patricia. The Verbally Abusive Relationship . Avon: Adams Media Corporation, 1996. 3. Feldmeth, J.R. & M. Finley. We Weep for Ourselves and Our Children: A Christian Guide for Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse . San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990. 4. Heitritter, Lynn & Jeanette Vought. Helping Victims of Sexual Abuse: A Sensitive Biblical Guide for Counselors, Victims, and Families. Minneapolis: Bethany House, 2006. 5. Pillari, V. Scapegoating in Families: Intergenerational Patterns of Physical and Emotional Abuse . New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1991. Christian Caregiving 1. Collins, Gary R. How To Be a People Helper . Carol Springs: Tyndale House Publisher, Inc., 1995. 2. Haugk, Kenneth C. Christian Caregiving. Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984. Depression 1. Biebel, David B. D. Min. & Harold G. Koenig, M.D. New Light on Depression: Help, Hope, and Answers for the Depressed & Those Who Love Them. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004. 2. Poinsett, Brenda. When the Saints Sing the Blues: Understanding Depression through the Lives of Job, Naomi, Paul, and Others . Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2006. Divorce 1. Carter, Les, Ph.D. Grace and Divorce . San Francisco: Jossey-B ass, 2005. 2. Smoke, Jim. Growing Through Divorce . Irving: Harvest House, 1976. Eating Disorders 1. Minirth, Dr. Frank, Dr. Paul Meier, Dr. Robert Hemfelt, Dr. Sharon Sneed, and Don Hawkins. Love Hunger: Recovery from Food Addiction . New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1990. 2. Vredevelt, Pam, Dr. Deborah Newman, Harry Beverly & Dr. -

Uncovering and Recovering the Popular Romance Novel A

Uncovering and Recovering the Popular Romance Novel A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Jayashree Kamble IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Timothy Brennan December 2008 © Jayashree Sambhaji Kamble, December 2008 Acknowledgements I thank the members of my dissertation committee, particularly my adviser, Dr. Tim Brennan. Your faith and guidance have been invaluable gifts, your work an inspiration. My thanks also go to other members of the faculty and staff in the English Department at the University of Minnesota, who have helped me negotiate the path to this moment. My graduate career has been supported by fellowships and grants from the University of Minnesota’s Graduate School, the University of Minnesota’s Department of English, the University of Minnesota’s Graduate and Professional Student Assembly, and the Romance Writers of America, and I convey my thanks to all of them. Most of all, I would like to express my gratitude to my long-suffering family and friends, who have been patient, generous, understanding, and supportive. Sunil, Teresa, Kristin, Madhurima, Kris, Katie, Kirsten, Anne, and the many others who have encouraged me— I consider myself very lucky to have your affection. Shukriya. Merci. Dhanyavad. i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Shashikala Kamble and Sambhaji Kamble. ii Abstract Popular romance novels are a twentieth- and twenty-first century literary form defined by a material association with pulp publishing, a conceptual one with courtship narrative, and a brand association with particular author-publisher combinations. -

Mills & Boon Books and How to Find Them

Document generated on 09/27/2021 8:54 p.m. Mémoires du livre Studies in Book Culture #loveyourshelfie Mills & Boon books and how to find them Lisa Fletcher, Jodi McAlister, Kurt Temple and Kathleen Williams La circulation de l’imprimé entre France et États-Unis à l’ère des Article abstract révolutions “Mills & Boon” has become shorthand for “trashy” entertainment, yet little is Franco-American Networks of Print in the Age of Revolutions known about how the books are treated materially in their circulation. This Volume 11, Number 1, Fall 2019 article reports on a project that followed the material lives and afterlives of 50 Australian-authored novels published by Harlequin Mills & Boon between 1996 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1066945ar and 2016. We analyze visual and textual data about these books collected via DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1066945ar social media to explore uses and values attached to category romance. First, we show that the books’ ongoing circulation is due both to their publishers’ practices, and to the behaviours of genre insiders. Second, we note that most See table of contents participants demonstrated “genre competence” and genre-based sociality, confirming the highly networked nature of the romance “genre world.” Third, we find that category romance is routinely shelved apart from other books, Publisher(s) explicitly marking them as distinctive. Finally, we argue that “shelfies” of romance collections undercut notions of trash by reframing them as treasure. Groupe de recherches et d’études sur le livre au Québec ISSN 1920-602X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Fletcher, L., McAlister, J., Temple, K. -

Adult Fiction Audiobooks on Cd | Updated April 2015

CASE MEMORIAL LIBRARY | ADULT FICTION AUDIOBOOKS ON CD | UPDATED APRIL 2015 AUTHOR TITLE Adams, Richard, 1920- Watership Down [sound recording] / Richard Adams. Adiga, Aravind. The white tiger [sound recording] / by Aravind Adiga. Adler, Elizabeth (Elizabeth A.) The house in Amalfi [sound recording] / by Elizabeth Adler. Albom, Mitch, author The first phone call from heaven [sound recording] / Mitch Albom. Albom, Mitch, 1958- For one more day [sound recording] / Mitch Albom. Albom, Mitch, 1958- The five people you meet in heaven [sound recording] / Mitch Albom. Alcott, Kate, author. The daring ladies of Lowell [sound recording] / Kate Alcott. Allende, Isabel. Maya's notebook [sound recording] / Isabel Allende. Anderson, Kevin J., 1962- The last days of Krypton [sound recording] / Kevin J. Anderson. Andrews, Mary Kay, 1954- Ladies' night [sound recording] : [a novel] / Mary Kay Andrews. Andrews, Mary Kay, 1954- Savannah breeze [sound recording] / by Mary Kay Andrews. Andrews, Mary Kay, 1954- author. Christmas bliss [sound recording] / Mary Kay Andrews. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- A prisoner of birth [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- Best kept secret [sound recording] : a novel / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- False impression [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- Only time will tell [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- Paths of glory [sound recording] : a novel / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- author. Be careful what you wish for [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, author. Mightier than the sword [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Asimov, Isaac, 1920-1992. The caves of steel [sound recording] / Isaac Asimov. Asimov, Isaac, 1920-1992. The Robots of Dawn [sound recording] / Isaac Asimov. Atkinson, Kate.