Performing the Erotic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

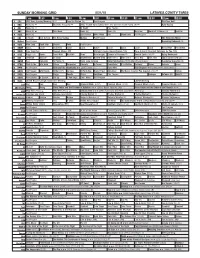

Sunday Morning Grid 5/31/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/31/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2015 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program The Simpsons Movie 13 MyNet Paid Program Becoming Redwood (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Easy Yoga Pain Deepak Chopra MD JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Pets. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Echoes of Creation Å Sacred Earth (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido Duro Pero Seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory

Skidmore College Creative Matter MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 MALS 5-20-2006 Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory Liane Fisher Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol Part of the Dance Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Liane, "Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory" (2006). MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019. 41. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the MALS at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Thesis Skidmore College Liane Fisher March 2006 Advisor: Isabel Brown Reader: Marc Andre Wiesmann Table of Contents Abstract .............................. ... .... .......................................... .......... ............................ ...................... 1 Chapter 1 : Introduction .. .................................................... ........... ..... ............ ..... ......... ............. 2 My thologyand Ballet ... ....... ... ........... ................... ....... ................... ....... ...... .................. 7 The Labyrinth My thologies .. ......................... .... ................. .......................................... -

Sexual Subversives Or Lonely Losers? Discourses of Resistance And

SEXUAL SUBVERSIVES OR LONELY LOSERS? DISCOURSES OF RESISTANCE AND CONTAINMENT IN WOMEN’S USE OF MALE HOMOEROTIC MEDIA by Nicole Susann Cormier Bachelor of Arts, Psychology, University of British Columbia: Okanagan, 2007 Master of Arts, Psychology, Ryerson University, 2010 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the program of Psychology Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Nicole Cormier, 2019 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Title: Sexual Subversives or Lonely Losers? Discourses of Resistance and Containment in Women’s Use of Male Homoerotic Media Doctor of Philosophy, 2019 Nicole Cormier, Clinical Psychology, Ryerson University Very little academic work to date has investigated women’s use of male homoerotic media (for notable exceptions, see Marks, 1996; McCutcheon & Bishop, 2015; Neville, 2015; Ramsay, 2017; Salmon & Symons, 2004). The purpose of this dissertation is to examine the potential role of male homoerotic media, including gay pornography, slash fiction, and Yaoi, in facilitating women’s sexual desire, fantasy, and subjectivity – and the ways in which this expansion is circumscribed by dominant discourses regulating women’s gendered and sexual subjectivities. -

Courting Trouble: a Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice

Courting Trouble: a Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40046518 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Courting Trouble: A Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice A dissertation presented by Holly Wood To The Harvard University Department of Sociology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Sociology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May, 2017 © Copyright by Holly Wood 2017 All Rights Reserved Dissertation Advisor: Professor Jocelyn Viterna Holly Wood Courting Trouble: A Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice Abstract Sociology recognizes marriage and family formation as two consequential events in an adult’s lifecourse. But as young people spend more of their lives childless and unpartnered, scholars recognize a dearth of academic insight into the processes by which single adults form romantic relationships in the lengthening years between adolescence and betrothal. As the average age of first marriage creeps upwards, this lacuna inhibits sociological appreciation for the ways in which class, gender and sexuality entangle in the lives of single adults to condition sexual behavior and how these behaviors might, in turn, contribute to the reproduction of social inequality. -

Donaheys-2019-Dancing-With-The

Join us in 2019 for the ultimate Weekend Break with the Stars of Strictly Come Dancing Enjoy 3 days of spectacular dance showcases as your favourite Strictly Come Dancing Stars perform up close & personal for a truly intimate experience unlike any other. ‘Donahey’s run the best dance weekends in the country….’ Kevin Clifton See what the Strictly Stars say about Donahey’s weekend breaks, read guest reviews, see photos, videos, 360 tours & more, visit www.donaheys.co.uk HOW TO BOOK Book securely online at www.donaheys.co.uk Call Freephone 0800 160 1770 Mon – Fri 9am – 3pm What’s included… Friday & Saturday Dinner, Bed & Breakfast at 3 hours of dance classes with Donahey’s fabulous 4* & 5* Resort Hotels highly experienced dance teachers in our additional ballroom. Floor-side reserved table to enjoy three days of Dance Showcases from the stars of BBC Two nights of dancing in stunning air Strictly Come Dancing & Champions of the conditioned Ballrooms. Dancing World – up close & personal. Saturday night Black Tie Ball starring The 4 hours of dance lessons with the stars of Tony Greenwood 15-piece Ballroom & Latin Strictly Come Dancing & Champions of the Big Band. Dancing World – guaranteed for everyone and tailored specifically to your dance level - from Exclusive ‘Red Carpet Strictly Photo new beginners, Improvers to Intermediates. Calls’ to grab those all-important souvenir photographs of the Strictly Celebrities. Find out the all the juicy Strictly gossip first hand from the Strictly stars with our Spectacular Sunday afternoon Grand-Finale fun Q&A sessions - plus maybe ask your dance showcase. -

Finding Aid for Bolender Collection

KANSAS CITY BALLET ARCHIVES BOLENDER COLLECTION Bolender, Todd (1914-2006) Personal Collection, 1924-2006 44 linear feet 32 document boxes 9 oversize boxes (15”x19”x3”) 2 oversize boxes (17”x21”x3”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x4”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x6”) 8 storage boxes 2 storage tubes; 1 trunk lid; 1 garment bag Scope and Contents The Bolender Collection contains personal papers and artifacts of Todd Bolender, dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet director. Bolender spent the final third of his 70-year career in Kansas City, as Artistic Director of the Kansas City Ballet 1981-1995 (Missouri State Ballet 1986- 2000) and Director Emeritus, 1996-2006. Bolender’s records constitute the first processed collection of the Kansas City Ballet Archives. The collection spans Bolender’s lifetime with the bulk of records dating after 1960. The Bolender material consists of the following: Artifacts and memorabilia Artwork Books Choreography Correspondence General files Kansas City Ballet (KCB) / State Ballet of Missouri (SBM) files Music scores Notebooks, calendars, address books Photographs Postcard collection Press clippings and articles Publications – dance journals, art catalogs, publicity materials Programs – dance and theatre Video and audio tapes LK/January 2018 Bolender Collection, KCB Archives (continued) Chronology 1914 Born February 27 in Canton, Ohio, son of Charles and Hazel Humphries Bolender 1931 Studied theatrical dance in New York City 1933 Moved to New York City 1936-44 Performed with American Ballet, founded by -

Global Infatuation: Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts. the Case of Harlequin Enterprises and Sweden

GlobalGlobal Infatuation InfatuationExplorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts the case of harlequin enterprises and sweden HemmungsEvaEva Hemmungs Wirtén Wirtén Skrifter utgivna av Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala Publications from the Section for Sociology of Literature at the Department of Literature, Uppsala University Nr 38 Global Infatuation Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts the case of harlequin enterprises and sweden Eva Hemmungs Wirtén Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala Section for Sociology of Literature at the Department of Literature, Uppsala University Uppsala 1998 Till Mamma och minnet av Pappa Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in literature presented at Uppsala University in 1998 Abstract Hemmungs Wirtén, E. 1998: Global Infatuation: Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts. The Case of Harlequin Enterprises and Sweden. Skrifter utgivna av Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala. Publications from the Section for Sociology of Literature at the Department of Literature, Uppsala University, 38. 272 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-85178-28-4. English text. This dissertation deals with the Canadian category publisher Harlequin Enterprises. Operating in a hundred markets and publishing in twenty-four languages around the world, Harlequin Enterprises exempliıes the increasingly transnational character of publishing and the media. This book takes the Stockholm-based Scandinavian subsidiary Förlaget Harlequin as a case-study to analyze the complexities involved in the transposition of Harlequin romances from one cultural context into another. Using a combination of theoretical and empirical approaches it is argued that the local process of translation and editing – here referred to as transediting – has a fundamental impact on how the global book becomes local. -

Dedicated to Line Dance

The monthly magazine dedicated to Line dancing Issue: 168 • £3 Natalie Thurlow DEDICATED TO LINE DANCE Photo: Arif Gardner 0 4 9 771366 650031 14 DANCES INCLUDING : LEONA’S LETTER • TEACH THE WORLD • DREAM OF YOU • TENNESSEE WALTZ SURPRISE cover 168.indd 1 31/03/2010 15:36 1085391 1085391 HH.indd 1 31/03/2010 15:38 april 2010 Editorial and Advertising Clare House 166 Lord Street Southport, PR9 0QA Dear Dancers Tel: 01704 392300 Fax: 01704 501678 Fanfare and drums at the Subscription Enquiries ready! This is the time in Tel: 01704 392300 [email protected] the magazine’s life when we ask our subscribers their Agent Enquiries opinions and thoughts on the Tel: 01704 392353 [email protected] magazine. A survey, like the one you are about to discover Web Support within these pages is a really Tel: 01704 392333 important measure of how the [email protected] magazine is doing. What can Publisher we improve? What should we Betty Drummond get rid of? Are we perfect as we [email protected] are (ok, ok stop laughing!)? In Managing Editor other words, this is one chance you have to let us Laurent Saletto know what you want, what you really really want. [email protected] Editorial Assistant Some people don’t bother with surveys of this kind as they think “No one will do anything Dawn Middleton anyway!” Well I can assure you that every entry will be scanned, discussed and entered into a [email protected] database out of which we will be able to shape the magazine into an even better product. -

DANCING TIMES a Publication of the Minnesota Chapter 2011 of USA Dance October 2013

MINNESOTA DANCING TIMES A publication of the Minnesota Chapter 2011 of USA Dance October 2013 Photo from the U of M’s Fall into Dance event by Kevin Viratyosin INSIDE THIS ISSUE: STUDIO OPENINGS AND CLOSINGS, U OF M BALLROOM DANCE CLUB, DANCING TO FIGHT MS, & MORE! Join us for USA Dance MN's DANCERS' NIGHT OUT Upcoming Dances Want to dance? Dancers’ Night Out lists social dance events in Minnesota. Want to see your dance listed here? Email the details to [email protected]. BECOME A USA DANCE MN MEMBER Wed 10/2 - West Coast Swing Dance Party; Thu 10/17 - Variety Dance; Dancers Studio, AT OUR DANCE AND GET IN FREE! Dancers Studio, 415 Pascal St. 415 Pascal St. N, St. Paul; 9-10; 651 Email: [email protected] N, St. Paul; 9-10; 651 641 0777 or 641 0777 or www.dancersstudio. Web: www.usadance-mn.org www.dancersstudio.com com Thu 10/3 - Variety Dance; Dancers Studio, Fri 10/18 - Grand Opening Party; 415 Pascal St. N, St. Paul; 9-10; 651 DanceLife Ballroom, 6015 Lyndale 641 0777 or www.dancersstudio. Ave S, Mpls; Free general dancing, October com lesson, and performances for Sun 10/6 - FREE Beginner American DanceLife Ballroom's grand Saturday, October 19th Cha Cha Class; Balance opening 7-8 pm Viennese Waltz Lesson Pointe Studios, 508 W 36th St, Sat 10/19 - USA Dance; ERV Dance Instructor: Eliecer Ramirez Vargas Minneapolis; 2:00-3:30; instructor Studios, 816 Mainstreet, Hopkins; Jeff Nehrbass; 952 922 8612 Viennese waltz lesson at 7, dance 8-11 pm Variety Dance Sun 10/6 - Ballroom Dance Party; Tapestry 8-11; $10, $7 USA Dance members Music DJ: Eliecer Ramirez Vargas Folkdance Center, 3748 Minnehaha Sun 10/20 - FREE Beginner American Ave, Mpls; Cha cha lesson with Cha Cha Class; Balance $7 USA Dance members Shinya McHenry at 6, variety Pointe Studios, 508 W 36th St, $10 Non-members dance 7-10; $10, $8 Tapestry Minneapolis; 2:00-3:30; instructor members; 612 722 2914 or www. -

Contributions by Employer

2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT HOME / CAMPAIGN FINANCE REPORTS AND DATA / PRESIDENTIAL REPORTS / 2008 APRIL MONTHLY / REPORT FOR C00431569 / CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT PO Box 101436 Arlington, Virginia 22210 FEC Committee ID #: C00431569 This report contains activity for a Primary Election Report type: April Monthly This Report is an Amendment Filed 05/22/2008 EMPLOYER SUM NO EMPLOYER WAS SUPPLIED 6,724,037.59 (N,P) ENERGY, INC. 800.00 (SELF) 500.00 (SELF) DOUGLASS & ASSOCI 200.00 - 175.00 1)SAN FRANCISCO PARATRAN 10.50 1-800-FLOWERS.COM 10.00 101 CASINO 187.65 115 R&P BEER 50.00 1199 NATIONAL BENEFIT FU 120.00 1199 SEIU 210.00 1199SEIU BENEFIT FUNDS 45.00 11I NETWORKS INC 500.00 11TH HOUR PRODUCTIONS, L 250.00 1291/2 JAZZ GRILLE 400.00 15 WEST REALTY ASSOCIATES 250.00 1730 CORP. 140.00 1800FLOWERS.COM 100.00 1ST FRANKLIN FINANCIAL 210.00 20 CENTURY FOX TELEVISIO 150.00 20TH CENTURY FOX 250.00 20TH CENTURY FOX FILM CO 50.00 20TH TELEVISION (FOX) 349.15 21ST CENTURY 100.00 24 SEVEN INC 500.00 24SEVEN INC 100.00 3 KIDS TICKETS INC 121.00 3 VILLAGE CENTRAL SCHOOL 250.00 3000BC 205.00 312 WEST 58TH CORP 2,000.00 321 MANAGEMENT 150.00 321 THEATRICAL MGT 100.00 http://docquery.fec.gov/pres/2008/M4/C00431569/A_EMPLOYER_C00431569.html 1/336 2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT 333 WEST END TENANTS COR 100.00 360 PICTURES 150.00 3B MANUFACTURING 70.00 3D INVESTMENTS 50.00 3D LEADERSHIP, LLC 50.00 3H TECHNOLOGY 100.00 3M 629.18 3M COMPANY 550.00 4-C (SOCIAL SERVICE AGEN 100.00 402EIGHT AVE CORP 2,500.00 47 PICTURES, INC. -

NEWSLETTER AUGUST 2018.Cdr

Issue 35 August 2018 English/South African Lewis Pugh hortly after 6am on 12 July, the heroic oceans ceramics of the Victorian era. His mother, Margery Pugh campaigner Lewis Pugh set out to swim the length of was a Senior Nursing Sister in Queen Alexandra's Royal Sthe English Channel - some 330 miles - in under 50 Naval Nursing Service. days. And he did it - reaching Dover on the 29th August Pugh grew up on the edge of Dartmoor in Devon. He was after 49 days. educated at Mount Kelly School in Tavistock. When he was 10 years old his family emigrated to South Africa. He continued his schooling at St Andrew's College in Grahamstown and later at Camps Bay High School in Cape Town. He went on to read politics and law at the University of Cape Town and graduated at the top of his Masters class. In his mid-twenties he returned to England where he read International Law at Jesus College, Cambridge and then worked as a maritime lawyer in the City of London for a number of years. During this time he concurrently served as a Reservist in the British Special Air Service. Pugh had his first real swimming lesson in 1986, at the age of 17. One month later he swam from Robben Island (where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned) to Cape Town. In 1992 he swam across the English Channel. In 2002 he broke the record for the fastest time for swimming around Robben Island. In battling through storms, jellyfish and a painful shoulder He was the first person to swim around Cape Agulhas (the injury, Lewis has shown grit, courage and inspirational southernmost point in Africa), the Cape of Good Hope, and leadership. -

Film, Philosophy Andreligion

FILM, PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION Edited by William H. U. Anderson Concordia University of Edmonton Alberta, Canada Series in Philosophy of Religion Copyright © 2022 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy of Religion Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942573 ISBN: 978-1-64889-292-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: "Rendered cinema fimstrip", iStock.com/gl0ck To all the students who have educated me throughout the years and are a constant source of inspiration. It’s like a splinter in your mind. ~ The Matrix Table of contents List of Contributors xi Acknowledgements xv Introduction xvii William H.