Narrative in Herman Melville's Moby Dick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

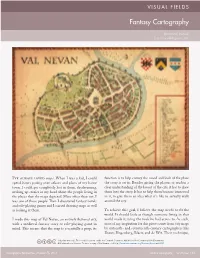

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

The Novel Map

The Novel Map The Novel Map Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction Patrick M. Bray northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2013 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2013. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Bray, Patrick M. The Novel Map: Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2013. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and the earlier version of chapter 4 as outlined in the Author’s Note For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Author’s Note xiii Introduction Here -

Dissertation Final

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title LIterature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nj845hz Author Jones, Ruth Elizabeth Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 © Copyright by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille by Ruth Elizabeth Jones Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Patrick Coleman, Chair This dissertation is concerned with the construction of the image of the city in twentieth- century Francophone writing that takes as its primary objects the representation of the city in the work of Driss Chraïbi and Abdelkebir Khatibi (Casablanca), Francine Noël (Montreal), and Jean-Claude Izzo (Marseille). The different stylistic iterations of the post Second World War novel offered by these writers, from Khatibi’s experimental autobiography to Izzo’s noir fiction, provide the basis of an analysis of the connections between literary representation and the changing urban environments of Casablanca, Montreal, and Marseille. Relying on planning documents, historical analyses, and urban theory, as well as architectural, political, and literary discourse, to understand the fabric of the cities that surround novels’ representations, the dissertation argues that the perceptual descriptions that enrich these narratives of urban life help to characterize new ways of seeing and knowing the complex spaces of each of the cities. -

Fake Maps: How I Use Fantasy, Lies, and Misinformation to Understand Identity and Place

DOI: 10.14714/CP92.1534 VISUAL FIELDS Fake Maps: How I Use Fantasy, Lies, and Misinformation to Understand Identity and Place Lordy Rodriguez Represented by Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco [email protected] There were two maps that really influenced me as I was with the words Houston and New York in it, along with growing up in suburban Texas in the ’80s. The first was a number of other places that were important to me. Just a map of Middle Earth found in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The like the penciled maps I made in the fifth grade, I made Hobbit and the other was a map of the spice planet Arrakis more and more of them, but this time with a more de- from Frank Herbert’s Dune. Around fifth grade, I began veloped aesthetic language. I played around with text and to emulate those maps by creating my own based on imag- colors, and experimented with different media. It wasn’t ined planets and civilizations. They were crude drawings, long until I made the decision to start a long-term series made with a #2 pencil on typing paper. And I made tons based on this direction, which lasted for the next ten years: of them. I had a whole binder full of these drawings, with the America Series. countries that had names like Sh’kr—which, in my head, was pronounced sha-keer. Maps, so often meant to represent reality, instead solidified worlds of fantasy and fiction. Of course, I was not thinking critically about car- tography in this way when I was in grade school, but those fantasy maps laid the foundation for me to explore mapping again in the late ’90s. -

Middle Earth to Panem

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUPUIScholarWorks infoteCh Use a combination of books and technology to bring the world of Middle Earth maps alive for your students. BOOKS WITH MAPS IN THE SCHOOL LIBRARY to Panem School librarians can use the maps in popular books for children and young adults to jumpstart twenty-fi rst-century skills related Maps of Imaginary Places to analyzing primary sources, using online map and satellite im- age resources, and constructing maps. The Standards for the 21st as Invitations to Reading Century Learner stress the importance of understanding text in all formats, including maps. Maps play a supporting role in some books for youth, but in annette Lamb and Larry johnson others they are an integral part of the story line. In a study of chil- dren’s books, Jeffrey Patton and Nancy Ryckman (1990) identifi ed a continuum of purposes for maps, from simple to complex. At ogwarts, Panem, Middle Earth, one end of the spectrum, maps were used to illustrate the general and the Hundred Acre Wood . setting of the book. At the intermediate point, maps showed where the story occurred or how characters were connected to a setting. these may be fi ctional places, At the complex end of the continuum, the map explained spatial H elements of the story line, such as a character’s journey or clues but they are brought to life in books. While J. K. Rowling and Suzanne Col- in a mystery. Regardless of the author’s approach, book maps can be excit- lins chose to leave their worlds up to ing tools in teaching, learning, and promoting the joy of reading. -

The City As Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1979 The City as Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow Yashoda Nandan Singh Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Singh, Yashoda Nandan, "The City as Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow" (1979). Dissertations. 1839. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Yashoda Nandan Singh THE CITY AS METAPHOR IN SELECTED NOVELS OF JA..~S PURDY A...'ID SAUL BELLO\Y by Yashoda Nandan Singh A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School ', of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful to Professor Eileen Baldeshwiler for her guidance, patience, and discerning comments throughout the writing of this dissertation. She insisted on high intellectual standards and complete intelligibility, and I hope I have not disappointed her. Also, I must thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman and Gene D. Phillips, S.J., for serving on my dissertation committee and for their valuable suggestions. A word of thanks to Mrs. Jo Mahoney for her preparation of the final typescript. -

Locating Lost City Radio by Meredith Perry

Spring 2007 55 BOOKS Locating Lost City Radio By Meredith Perry Lost City Radio By Daniel Alarcón 272 pages, HarperCollins. $24.95 efore beginning his reading of Lost City Radio, author Daniel BAlarcón offers a disclaimer, “I didn’t set this novel in Peru. I set this novel in an unnamed Latin American country, in an unnamed Latin American city.” Seconds later, as Alarcón is framing the excerpt he is about to read, he says, “This is about the night the war finally became real in Lima.” Then he pauses and corrects himself, “Not in Lima, in this made-up, fictional city.” Standing before the Peruvian Consul General, Alarcón, winks, “Nothing like this ever happened in Peru.” Lost City Radio, Alarcón’s first novel, chronicles two days in the life of Norma, a news announcer for a national radio program. With thousands missing due to civil war and economic dislocation, Norma’s radio program provides a forum for callers hoping to reconnect with their lost family members, lovers and friends. Ten years prior, Norma’s own husband Rey disappeared during the waning days of the war in a village on the outskirts of the jungle. The narrative begins when Victor, an 11-year-old boy from the jungle village art courtesyCover of Harper Collins. where Norma’s husband disappeared, arrives at the station with a list of the village’s missing. unflattering detail, the lives of Norma, Rey and Victor. When Norma recognizes her husband’s nom-de-guerre, Despite his disclaimer, Alarcón readily admits that Peru she is forced to come to terms with her life, her husband’s is the template from which derives his lost city and unnamed secrets and Victor’s mysterious origins — in short, “how country. -

Virtual Worlds , Fiction, and Reality

Virtual worlDs, Fiction, anD reality mundos virtuales, fiCCión y realidad ILkkA mAuNu NIINILuOTO University of Helsinki, Finland. [email protected] RECIbIDO EL 13 DE juLIO DE 2011 y APRObADO EL 30 DE AGOSTO DE 2011 resumen abstract Mi objetivo en este artículo es plantear My aim in this paper is to raise and discuss y discutir algunas de las preguntas some philosophical questions about Virtual filosóficas sobre la Realidad Virtual (RV). Reality (VR). The most fundamental El problema fundamental se refiere a problem concerns the ontological nature of la naturaleza ontológica de la realidad VR: is it real or fictional? Is VR comparable virtual: ¿es real o ficticia? ¿La RV es to illusions, hallucinations, dreams, comparable a ilusiones, alucinaciones, or worlds of fiction? Are traditional sueños, o mundos de ficción? ¿Son todas philosophical categories at all sufficient to las categorías filosóficas tradicionales give us understanding of the phenomenon suficientes para darnos la comprensión of VR? In approaching these questions, I del fenómeno de la RV? Para abordar shall employ possible world semantics estas cuestiones, emplearé como mis and logical theories of perception and herramientas filosóficas la semántica de imagination as my philosophical tools. My mundos posibles y las teorías lógicas main conclusion is that VR is comparable de la percepción y la imaginación. Mi to a 3-D picture which can be seen from conclusión principal es que la RV es the inside. comparable a una imagen en 3-D que puede ser vista desde el interior. palabras claVe Key worDs Ficción, alucinación, imaginación, Fiction, hallucination, imagination, percepción, realidad, realidad virtual. -

Mimesis, Romance, Novel: Representation of Milieu in the Monk and Nostromo

MIMESIS, ROMANCE, NOVEL: REPRESENTATION OF MILIEU IN THE MONK AND NOSTROMO. A Thesis submitted to the faculty of ry < San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for ^3^ thC Degree Master of Arts In English: Literature by Sudarshan Ramani San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Sudarshan Ramani 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Mimesis, Romance, Novel: Representation of Milieu in The Monk and Nostromo by Sudarshan Ramani, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in English: Literature at San Francisco State University. MIMESIS, ROMANCE, NOVEL: REPRESENTATION OF MILIEU IN THE MONK AND NOSTROMO Sudarshan Ramani San Francisco, California 2018 ABSTRACT: The century that separates M. G. Lewis’s The Monk (1796) and Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo (1904) is a century of historical and aesthetic revolution. Paired together, both novels reveal the continuity of the problem of representing reality. Both of these novels are original products of an international outlook that mixes high and low culture, the experimental and the popular, the folkloric and the avant-garde. When viewed in this context, it becomes possible to see the historical and the contemporary in a gothic novel like The Monk, and the gothic and the fantastic in a historical novel like Nostromo. Following the example of Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis, this thesis focuses on the presence of contingent and dynamic elements in the narrative style of these two novels so as to better explain their originality, and the ways in which both authors continue to challenge the static pillars of tradition and cultural inheritance. -

Young Adults in the Urban Consumer Society of the 1980S in Janowitz

The Self in Trouble: Young Adults in the Urban Consumer Society of the 1980s in Janowitz, Ellis, and McInerney Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie in der Fakultät für Philologie der RUHR-UNIVERSITÄT BOCHUM vorgelegt von GREGOR WEIBELS-BALTHAUS Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Fakultät für Philologie der Ruhr-Universität Bochum Referent: Prof. Dr. David Galloway Koreferentin: Prof. Dr. Kornelia Freitag Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 11. Mai 2005 Danksagungen Ich bedanke mich für die Promotionsförderung, die ich von der Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung (Institut für Begabtenförderung) erhalten habe. Meinem Lehrer, Herrn Prof. Dr. David Galloway, gilt mein besonderer Dank für seine kompetente Unterstützung und für sein nicht erlahmendes Wohlwollen, das er mir und meinem Projekt allzeit entgegenbrachte. Vielfache Anregungen erhielt ich von Edward de Vries, Michael Wüstenfeld und Doerthe Wagelaar. Meiner Frau, Dr. med. Bettina Balthaus, danke ich in Liebe für ihre Hilfe und für ihr Verständnis, das sie auch dann noch aufbrachte, wenn niemand sonst mehr verstand. Table of Contents 1 Introduction 8 1.1 A Literary-Commercial Phenomenon 8 1.2 The Authors and Their Works 14 1.3 Relevant Criticism 18 1.4 The Guiding Questions 23 2 The Rise and Demise of the Self 27 2.1 The Rise of the Imperial Self of Modernity 28 2.1.1 From the Origins to the Modernist Self 28 2.1.2 The Emergence of the Inner-directed Character in America 31 2.1.2.1 The Puritan Heritage 33 2.1.2.2 The Legacy of the Frontier 36 2.2 The Self on the Retreat -

Fictionality, Wieland, and the Eighteenth• Century German Novel 1

Noble Lies, Slant Truths, Necessary Angels From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Noble Lies, Slant Truths, Necessary Angels Aspects of Fictionality in the Novels of Christoph Martin Wieland ellis shookman UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 118 Copyright © 1997 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Shookman, Ellis. Noble Lies, Slant Truths, Nec- essary Angels: Aspects of Fictionality in the Novels of Christoph Martin Wieland. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. doi: https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469656502_Shookman Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Shookman, Ellis. Title: Noble lies, slant truths, necessary angels: Aspects of fictionality in the novels of Christoph Martin Wieland / by Ellis Shookman. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 118. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1997] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references.