Magical Realism As Literary Activism in the Post-Cold War US Ethnic Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Strategy-To-Win-An-Election-Lessons

WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 i The Institute of International Studies (IIS), Department of International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada, is a research institution focused on the study on phenomenon in international relations, whether on theoretical or practical level. The study is based on the researches oriented to problem solving, with innovative and collaborative organization, by involving researcher resources with reliable capacity and tight society social network. As its commitments toward just, peace and civility values through actions, reflections and emancipations. In order to design a more specific and on target activity, The Institute developed four core research clusters on Globalization and Cities Development, Peace Building and Radical Violence, Humanitarian Action and Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. This institute also encourages a holistic study which is based on contempo- rary internationalSTRATEGY relations study scope TO and WIN approach. AN ELECTION: ii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 By Dafri Agussalim INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA iii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 Penulis: Dafri Agussalim Copyright© 2011, Dafri Agussalim Cover diolah dari: www.biogenidec.com dan http:www.foto.detik.com Diterbitkan oleh Institute of International Studies Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Gadjah Mada Cetakan I: 2011 x + 244 hlm; 14 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978-602-99702-7-2 Fisipol UGM Gedung Bulaksumur Sayap Utara Lt. 1 Jl. Sosio-Justisia, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281 Telp: 0274 563362 ext 115 Fax.0274 563362 ext.116 Website: http://www.iis-ugm.org E-mail: [email protected] iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is a revised version of my Master of Arts (MA) thesis, which was written between 1994-1995 in the Australian National University, Canberra Australia. -

EPIC and ROMANCE in the LORD of the RINGS Épica Y Romance En El Señor De Los Anillos

ISSN: 1989-9289 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14516/fdp.2016.007.001.002 EPIC AND ROMANCE IN THE LORD OF THE RINGS Épica y romance en El señor de los anillos Martin Simonson [email protected] Universidad del País Vasco, Vitoria-Gasteiz. España Fecha de receepción: 4-IV-2016 Fecha de aceptación: 5-V-2016 ABSTRACT: In the field of comparative literatureThe Lord of the Rings has been most frequently studied within the contexts of romance and epic. This approach, however, leaves out important generic aspects of the global picture, such as the narrative’s strong adherence to the novel genre and to mythic traditions beyond romance and epic narratives. If we choose one particular genre as the yardstick against which to measure the work’s success in narrative terms, we tend to end up with the conclusion that The Lord of the Rings does not quite make sense within the given limits of the genre in question. In Tolkien’s work there is a narrative and stylistic exploration of the different genres’ constraints in which the Western narrative traditions – myth, epic, romance, the novel, and their respective subgenres – interact in a pre- viously unknown but still very much coherent world that, because of the particular cohesion required by such a chronotope, exhibits a clear contextualization of references to the previous traditions. As opposed to many contemporary literary expressions, the ensuing absence of irony and parody creates a generic dialogue, in which the various narrative traditions explore and interrogate each other’s limits without rendering the others absurdly incompatible, ridic- ulous or superfluous. -

In the Last Year Or So, Scholarship in American Literature Has Been

REVIEWS In the last year or so, scholarship in American Literature has been extended by the appearance of three exciting series which reassess, synthesize, and clarify the work and reputation of major American writers and literary groups. MASAJ begins with this issue reviews of representative titles in Twayne's United States Authors Series (Sylvia Bowman, Indiana University, General Editor); Barnes & Noble's American Authors and Critics Series (Foster Provost and John Mahoney, Duquesne University, General Editors); and The University of Minnesota Pamphlets on American Writers (William Van O'Connor, Allen Tate, Leonard Unger, and Robert Penn Warren, Editors), and will continue such reviews until the various series are completed. Twayne's United States Authors Series (TUSAS), (Hardback Editions) JOHN GREENLEAF WHITTIER. By Lewis Leary. New York: Twayne Pub lishers, Inc. 1961. $3.50. As a long overdue reappraisal, this book places Whittier squarely within the cultural context_of his age and then sympathetically, but objectively, ana lyzes his poetic achievement. Leary * s easy style and skillful use of quotations freshen the well-known facts of Whittier's life. Unlike previous biographers he never loses sight of the poet while considering Whittier's varied career as editor, politician and abolitionist. One whole chapter, "The Beauty of Holi ness ," presents Whittier1 s artistic beliefs and stands as one of the few extended treatments of his aesthetics in this century. Also Leary is not afraid to measure Whittier Ts limitations against major poets like Whitman and Emerson, and this approach does much to highlight Whittier's poetic successes. How ever, the book's real contribution is its illuminating examination of Whittier's artistry: the intricate expansion of theme by structure in "Snow-Bound," the tensions created by subtle Biblical references in "Ichabod, " and the graphic blending of legend and New England background in "Skipper Ireson's Ride." Even long forgotten poems like "The Cypress-Tree of Ceylon" reveal surprising poetic qualities. -

Myth Y La Magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2015 Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America Hannah R. Widdifield University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Widdifield, Hannah R., "Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3421 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Hannah R. Widdifield entitled "Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Lisi M. Schoenbach, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Allen R. Dunn, Urmila S. Seshagiri Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Hannah R. -

Refiguring Masculinity in Haitian Literature of Dictatorship, 1968-2010

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Dictating Manhood: Refiguring Masculinity in Haitian Literature of Dictatorship, 1968-2010 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of French and Francophone Studies By Ara Chi Jung EVANSTON, ILLINOIS March 2018 2 Abstract Dictating Manhood: Refiguring Masculinity in Haitian Literature of Dictatorship, 1968- 2010 explores the literary representations of masculinity under dictatorship. Through the works of Marie Vieux Chauvet, René Depestre, Frankétienne, Georges Castera, Kettly Mars and Dany Laferrière, my dissertation examines the effects of dictatorship on Haitian masculinity and assesses whether extreme oppression can be generative of alternative formulations of masculinity, especially with regard to power. For nearly thirty years, from 1957 to 1986, François and Jean-Claude Duvalier imposed a brutal totalitarian dictatorship that privileged tactics of fear, violence, and terror. Through their instrumentalization of terror and violence, the Duvaliers created a new hegemonic masculinity articulated through the nodes of power and domination. Moreover, Duvalierism developed and promoted a masculine identity which fueled itself through the exclusion and subordination of alternative masculinities, reflecting the autophagic reflex of the dictatorial machine which consumes its own resources in order to power itself. My dissertation probes the structure of Duvalierist masculinity and argues that dictatorial literature not only contests dominant discourses on masculinity, but offers a healing space in which to process the trauma of the dictatorship. 3 Acknowledgements There is a Korean proverb that says, “백지장도 맞들면 낫다.” It is better to lift together, even if it is just a blank sheet of paper. It means that it is always better to do something with the help of other people, even something as simple as lifting a single sheet of paper. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

Jerry Goodman (Chicago, Illinois, March 16, 1949) Is an American Violinist Best Known for Playing Electric Violin in the Bands T

Jerry Goodman (Chicago, Illinois, March 16, 1949) is an American violinist best known for playing electric violin in the bands The Flock and the jazz fusion Mahavishnu Orchestra. Goodman actually began his musical career as The Flock's roadie before joining the band on violin. Trained in the conservatory, both of his parents were in the string section of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. His uncle was the noted composer and jazz pianist Marty Rubenstein. After his 1970 appearance on John McLaughlin's album My Goal's Beyond, he became a member of McLaughlin's original Mahavishnu Orchestra lineup until the band broke up in 1973, and was viewed as a soloist of equal virtuosity to McLaughlin, keyboardist Jan Hammer and drummer Billy Cobham. In 1975, after Mahavishnu, Goodman recorded the album Like Children with Mahavishnu keyboard alumnus Jan Hammer. Starting in 1985 he recorded three solo albums for Private Music -- On the Future of Aviation, Ariel, and the live album It's Alive with luminaries such as Fred Simon and Jim Hines—and went on tour with his own band, as well as with Shadowfax and The Dixie Dregs. He scored Lily Tomlin's The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe and is the featured violinist on numerous film soundtracks, including Billy Crystal's Mr. Saturday Night and Steve Martin's Dirty Rotten Scoundrels . His violin can be heard on more than fifty albums from artists ranging from Toots Thielemans to Hall & Oates to Styx to Jordan Rudess to Choking Ghost to Derek Sherinian. Goodman has appeared on four of Sherinian's solo records - Inertia (2001), Black Utopia (2003), Mythology (2004), and Blood of the Snake (2006) In 1993, Goodman joined the American instrumental band, The Dixie Dregs, fronted by guitarist Steve Morse. -

African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies: AJCJS, Vol.4, No.1

African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies: AJCJS, Vol.8, Special Issue 1: Indigenous Perspectives and Counter Colonial Criminology November 2014 ISSN 1554-3897 Indigenous Feminists Are Too Sexy for Your Heteropatriarchal Settler Colonialism Andrea Smith University of California Abstract Within the creation myths of the United States, narratives portray Native peoples as hypersexualized and sexually desiring white men and women. Native men in captivity narratives are portrayed as wanting to rape white women and Native women such as Pocahontas are constituted as desiring the love and sexual attention of white men at the expense of her Native community. In either of these accounts of settler colonialism, Native men and women’s sexualities are read as out of control and unable to conform to white heteropatriarchy. Many Native peoples respond to these images by desexualizing our communities and conforming to heteronormativity in an attempt to avoid the violence of settler-colonialism. I interrogate these images and provide sex-positive alternatives for Native nation building as an important means of decolonizing Native America. Keywords Indigenous feminists, heteropatriarchy, settler colonialism, anti-violence. Introduction . Sexy futures for Native feminisms. Chris Finley (2012) Chris Finley signals a new direction emerging out of the Indigenous anti-violence movement in Canada and the United States. This strand of the anti-violence organizing and scholarship builds on the work of previous indigenous anti-violence advocates who have centered gender violence as central to anti-colonial struggle. However, as the issue of violence against Indigenous women gains increasing state recognition, this strand has focused on building indigenous autonomous responses to violence that are not state-centered. -

Fantasy Cartography

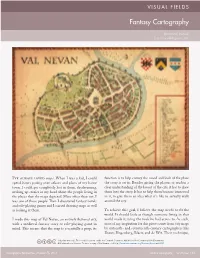

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

Beyond Blood Quantum: the Legal and Political Implications of Expanding Tribal Enrollment

American Indian Law Journal Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 8 12-15-2014 Beyond Blood Quantum: The Legal and Political Implications of Expanding Tribal Enrollment Tommy Miller Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj Part of the Cultural Heritage Law Commons, and the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Tommy (2014) "Beyond Blood Quantum: The Legal and Political Implications of Expanding Tribal Enrollment," American Indian Law Journal: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj/vol3/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Journal by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beyond Blood Quantum: The Legal and Political Implications of Expanding Tribal Enrollment Cover Page Footnote Tommy Miller is a 2015 J.D. Candidate at Harvard Law School and a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes. He would like to thank his family for their constant support and inspiration, Professor Joe Singer for his guidance, and the staff of the American Indian Law Journal for their hard work. This article is available in American Indian Law Journal: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj/vol3/iss1/8 AMERICAN INDIAN LAW JOURNAL Volume III, Issue I – Fall 2014 BEYOND BLOOD QUANTUM THE LEGAL AND POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS OF EXPANDING TRIBAL ENROLLMENT ∗ Tommy Miller INTRODUCTION Tribal nations take many different approaches to citizenship.