To Test an Idea: Menippean Satire in Lawrence Durrell's Avignon Quintet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lawrence Durrell's Bitter Lemons and Rodis Roufos

1Journal Nicholas of Mediterranean Coureas Studies, 2016 ISSN: 1016-3476 Vol. 25, No. 2: 000–000 CYPRUS AND THE NOT-SO-SOFT POWER OF CULTURAL POLITICS: LAWRENCE DURRELL‘S BITTER LEMONS AND RODIS ROUFOS‘ THE AGE OF BRONZE ARGYRO NICOLAOU Harvard University This article builds on postcolonial readings of Lawrence Durrell‘s work and offers a comparative analysis of Bitter Lemons and the 1960 novel The Age of Bronze by Rodis Roufos, a Greek diplomat and journalist, who wrote it in direct response to Durrell‘s text. My main objective is to show that any critical analysis of Durrell‘s work on Cyprus should take into account both the literary and political criticism that the work incited among the non-British, non-Anglophone intellectual circles of the time as well as the specific cultural political power dynamics that have allowed Durrell‘s work to dominate as the uncontested, monologic authority on the subject of Cyprus‘ decolonization. By presenting an extensive, in-depth textual analysis of a suppressed section of Roufos‘ novel, first published by David Roessel in 1994, my paper aims to demonstrate that beyond the veneer of its overwhelmingly positive reception, Bitter Lemons was in fact the subject of cross-cultural, international debate that bears testament to the capacity of cultural objects to shape political realities. Interpreting both texts as examples of cultural politics, the article also illustrates the powerful legacy of colonization in current European political discourse. Durrell’s Legacy on Cyprus It is ironic, yet in many ways entirely unsurprising, that the most famous book on Cyprus is a British author‘s account of the turbulent years of the National Organization of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA) uprising against the British crown from 1955 to 1959 and the Greek Cypriots‘ demand for Enosis, or political union with Greece. -

The Lawrence Durrell Journal, NS7 1999 - 2000

The International Lawrence Durrell Society The Herald Editors: Peter Baldwin Volume 41; September 2019 [NS-2] Steve Moore Founding Editor: Susan MacNiven The Herald - September, 2019 Welcome to The Herald NS [New Series] #2. We have enjoyed the feedback received thus far based on NS 1 and believe that what we have received is auspicious for going forward in the same vein. In this issue we choose to highlight a piece that is authored by ILDS’s president – Dr. Isabelle Keller- Privat, titled “Durrell’s Cyprus, another Private Country”. This is an excerpt from a presentation that she provided at the On Miracle Ground XX conference held in Chicago in 2017. We are also pleased to include a contribution from Françoise Kestsman-Durrell as well as from Noel Guckian, the current owner of the Mas Michel, occupied by Durrell from 1958 to 1966. In addition, we have interspersed some artwork by contributor Geoff Todd who has taken his inspiration for this series of images from Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet – look for the corresponding article from Mr. Todd, as well. The incomparable Grove Koger builds out our Durrell-related bibliography in his ‘Chart Room’. Peter Baldwin & Steve Moore, editors Sommières, Larry, the sun, the winter By Françoise Kestsman-Durrell Introduction Francoise Kestsman-Durrell was Lawrence Durrell’s companion from 1984 until his death in 1990. She wrote a preface for the book, Durrell à Sommières, published by Éditions Gaussen in 2018. A note on this book appeared in the last edition of The Herald, June 2019. Françoise has kindly allowed us to include this preface in The Herald. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

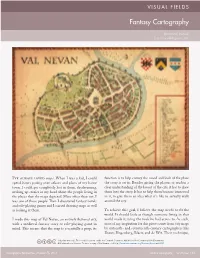

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

Grotesque Anatomies: Menippean Satire Since the Renaissance

Grotesque Anatomies Grotesque Anatomies: Menippean Satire since the Renaissance By David Musgrave Grotesque Anatomies: Menippean Satire since the Renaissance, by David Musgrave This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by David Musgrave All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5677-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5677-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ vi Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction: Menippean Satire and the Grotesque Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 40 Grotesque Transformation in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children: The Nose in Menippean Satire Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 64 Grotesque Association in Thomas de Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater and Thomas Love Peacock’s Gryll Grange: Utterance, Surdity and the Ruminant Stomach Chapter Four ............................................................................................. -

The Satyricon of Petronius: Genre, Wandering and Style Autor(Es): Teixeira, Cláudia; Ferreira, Paulo Sérgio Margarido; Leão

The Satyricon of Petronius: genre, wandering and style Teixeira, Cláudia; Ferreira, Paulo Sérgio Margarido; Leão, Delfim Autor(es): Ferreira Publicado por: Centro de Estudos Clássicos e Humanísticos URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/2402 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/978-989-721-060-0 Accessed : 6-Oct-2021 17:15:07 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt (Página deixada propositadamente em branco) Cláudia Teixeira University of Évora Delfim F. Leão University of Coimbra Paulo Sérgio Ferreira University of Coimbra TheSatyricon of Petronius Genre, Wandering and Style Translated from the Portuguese by Martin Earl ISBN DIGITAL: 978-989-721-060-0 DOI: HTTP://DX.DOI.ORG/10.14195/978-989-721-060-0 CONTENTS PREFACE 7 Cláudia Teixeira, Delfim F. -

Gerald Durrell English Author Commemoration in Jamshedpur , His Birth Place

Gerald Durrell English author Commemoration in Jamshedpur , his Birth place Durrell was born 90 years ago on 7 January 1925 in Jamshedpur. His father, Lawrence Samuel Durrell (1884-1928), was a very prominent contractor who, after being involved in the building of the Darjeeling railway, came to Jamshedpur. As an engineer, he built TISCO General Office, Tata Main Hospital, the Tinplate Co., the Indian Cable Co., the Enamelled Ironware Co. and undertook contractual work with them to build the earlier European Bungalows. He stayed at D/6 type European bungalow opposite Beldih Lake and describes it as sprawling and comfortable, with cool, shuttered rooms, a large veranda with bamboo screens against the heat of the sun, and a sizeable garden of lawn, shrubs and trees. After the death of his father in 1928, his mother, Louisa Dixie Durrell (1886-1964), returned to England with her three younger children – Leslie (1918-1983), Margaret (1920-2007) and Gerald (1925-1995) Lawrence (1912-1990), the eldest, had already moved to England . Gerald lived with his family on the Greek island of Corfu from 1935-1939 where began to collect and keep the local fauna as his pets and which was also the basis of his book “My Family And Other Animals”. Home-schooled Gerald honed his descriptive skills in writing about animals. Many of those who appeared for the Senior Cambridge exams will recall “My Family And Other Animals” as a prescribed text book. His greatest achievement was the founding of the Jersey Zoo in 1959 as a center for the conservation of endangered species, and the creation of the Jersey Wildlife Conservation Trust (now the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust) in 1963. -

Rabelais' Pantagruel and Gargantua As Instruction Manuals

FROM POPULAR CULTURE TO ENLIGHTENMENT: RABELAIS’ PANTAGRUEL AND GARGANTUA AS INSTRUCTION MANUALS Ashley Robb A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August: 2012: Committee: Dr. Beatrice Guenther, Advisor Dr. Robert Berg ii ABSTRACT Dr. Beatrice Guenther, Advisor Popular references are a defining feature of François Rabelais’ Pantagruel and Gargantua. One cannot read either of these narratives without being exposed to a barrage of popular characters, imagery, and events. This study serves to elucidate Rabelais’ use of popular characters within Pantagruel and Gargantua by arguing that the author used these characters as instructional tools. The first component of this thesis will analyze the manner in which Rabelais makes use of his mythical protagonists in order to denounce the ideological use of myth. This study will also demonstrate how Rabelais uses popular characters in his second narrative, Gargantua, to evoke Erasmian evangelism. The final chapter of this thesis will examine several narrative techniques employed by Rabelais in order to transmit to his readers lessons on wisdom and truth. The culmination of these examples serves to show how Rabelais’ Pantagruel and Gargantua function as instruction manuals, by redefining and reclaiming what it means to be a Christian, and informing readers how to live a better, more evangelical, life. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. -

(2011), Pius Adesanmi Employs Menippean Sat- Ire to Show the Contradictions That Inhere in the African Continent

Institute of African Studies Carleton University (Ottawa, Canada) 2021 (9) !"#$%%"&#'(&)$*"'$#' +,-).,/,#$&/'01*$.&#' 2$)"*&)3*"4'0'5"&6$#7',1' +$3-'06"-$9-':,39*"';,)' &'<,3#)*=>'01*$.&' ?/3-,/&'?73#@&=, In !"#$%&'(")'*'+"#,)%-.'/0%12* (2011), Pius Adesanmi employs Menippean sat- ire to show the contradictions that inhere in the African continent. Te Menippean satiric method includes the interrogation of mental attitudes, the querying of inhu- mane orthodoxy as well as the re-negotiation of philosophical standpoints of persons, institutions and nations. Tis form of satire resembles the innuendoes and moral inclinations of some Nigerian folktales. Tis similarity largely informs Adesanmi’s imaginative dexterity in attacking ineptitude and shortcomings of the interrogated space. Indeed, with the combination of Menippean ridicule and the narratology of African folklore, the satirist, Adesanmi, is methodologically equipped to inveigh against the recklessness in Africa and to promote rectitude therein. Tis study, there- fore, examines the constituents of Menippean satire such as multiple viewpoint, dis- continuity, humour, and mind setting as preponderant elements in Adesanmi’s You’re Not a Country, Africa. Tese constituents have a distinct interface with the allegory and didacticism of African folklore all of which enable Adesanmi to foreground the need for renewal and rebirth in a promising continent. Keywords: Menippean, Satire, Postcolonial, Adesanmi A#)*,63.)$,# In reshaping the ofen misrepresented and manipulated history of Africa, cul- tural critics like Lewis Nkosi in Homeland and Exile (1965), Chinua Achebe in Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays 1965-1987 (1988) and Ngugi wa Tiong’o in Homecoming: Essays in African and Caribbean Literature, Culture and Politics Menippean Satire / Olusola Ogunbayo 72 (1972) are a few examples of fery satirists who demonstrate great intellection in re- focusing the distinctive cultures of Africa and in rebuking the inhumanity of certain aspects of Africa’s socio-cultural and political experiences. -

Indian Metaphysics in Lawrence Durrell's Novels

Indian Metaphysics in Lawrence Durrell’s Novels Indian Metaphysics in Lawrence Durrell’s Novels By C. Ravindran Nambiar Indian Metaphysics in Lawrence Durrell’s Novels, by C. Ravindran Nambiar This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by C. Ravindran Nambiar All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5315-1, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5315-6 Dedicated to my wife Prabha I know that the bone structure of my work is metaphysically solid, so to speak, and that’s what counts. —Lawrence Durrell TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. viii Foreword .................................................................................................... xi Dr. Corinne Alexandre-Garner Introduction ............................................................................................. xvii Prof. Ian S. MacNiven List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xxii Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Durrell -

![ILCEA, 28 | 2017, « Passages, Ancrage Dans La Littérature De Voyage » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 06 Mars 2017, Consulté Le 23 Septembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7867/ilcea-28-2017-%C2%AB-passages-ancrage-dans-la-litt%C3%A9rature-de-voyage-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-06-mars-2017-consult%C3%A9-le-23-septembre-2020-1117867.webp)

ILCEA, 28 | 2017, « Passages, Ancrage Dans La Littérature De Voyage » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 06 Mars 2017, Consulté Le 23 Septembre 2020

ILCEA Revue de l’Institut des langues et cultures d'Europe, Amérique, Afrique, Asie et Australie 28 | 2017 Passages, ancrage dans la littérature de voyage Catherine Delmas (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ilcea/4069 DOI : 10.4000/ilcea.4069 ISSN : 2101-0609 Éditeur UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Édition imprimée ISBN : 978-2-84310-374-2 ISSN : 1639-6073 Référence électronique Catherine Delmas (dir.), ILCEA, 28 | 2017, « Passages, ancrage dans la littérature de voyage » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 06 mars 2017, consulté le 23 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ ilcea/4069 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ilcea.4069 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 23 septembre 2020. © ILCEA 1 Les articles qui composent ce numéro portent sur la problématique du passage et de l’ancrage dans la littérature de voyage. Ils portent sur la littérature italienne, hispanique et anglophone, du Moyen Âge à l’ère contemporaine. La période, large, allant du Moyen Âge avec l’étude d’Enea Silvio Piccolomini, humaniste du XVe siècle dont Serge Stolf est le spécialiste, à l’ère contemporaine avec les articles d’Isabelle Keller-Privat portant sur Lawrence Durrell ou de Françoise Besson sur la relation de l’homme au monde, permet de mieux cerner le genre hybride de la littérature de voyage, la fonction du voyage et des usages des lieux traversés, comme le souligne Gilles Bertrand pour la Méditerranée, et la problématique posée par les notions de passage et d’ancrage. Le passage vers l’ailleurs que relate le récit de voyage met en lumière des points d’ancrage qui peuvent être géographiques, culturels, politiques et génériques, et a contrario l’ancrage peut être vecteur d’émancipation, d’ouverture à l’Autre, grâce au medium qu’est le texte. -

The Novel Map

The Novel Map The Novel Map Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction Patrick M. Bray northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2013 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2013. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Bray, Patrick M. The Novel Map: Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2013. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and the earlier version of chapter 4 as outlined in the Author’s Note For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Author’s Note xiii Introduction Here