Pantagruel and Gargantua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epic and Romance Essays on Medieval Literature W

EPIC AND ROMANCE ESSAYS ON MEDIEVAL LITERATURE W. P. KER PREFACE These essays are intended as a general description of some of the principal forms of narrative literature in the Middle Ages, and as a review of some of the more interesting works in each period. It is hardly necessary to say that the conclusion is one "in which nothing is concluded," and that whole tracts of literature have been barely touched on--the English metrical romances, the Middle High German poems, the ballads, Northern and Southern--which would require to be considered in any systematic treatment of this part of history. Many serious difficulties have been evaded (in Finnesburh, more particularly), and many things have been taken for granted, too easily. My apology must be that there seemed to be certain results available for criticism, apart from the more strict and scientific procedure which is required to solve the more difficult problems of Beowulf, or of the old Northern or the old French poetry. It is hoped that something may be gained by a less minute and exacting consideration of the whole field, and by an attempt to bring the more distant and dissociated parts of the subject into relation with one another, in one view. Some of these notes have been already used, in a course of three lectures at the Royal Institution, in March 1892, on "the Progress of Romance in the Middle Ages," and in lectures given at University College and elsewhere. The plot of the Dutch romance of Walewein was discussed in a paper submitted to the Folk-Lore Society two years ago, and published in the journal of the Society (Folk-Lore, vol. -

Évolution Du Personnage Épique Médiéval Sur L'exemple De

Dorota Pudo Université Jagellonne de Cracovie ÉVOLUTION DU PERSONNAGE ÉPIQUE MÉDIÉVAL SUR L’EXEMPLE DE QUELQUES TEXTES CONSACRÉS À GUILLAUME D’ORANGE ET À HUON DE BORDEAUX Le moyen âge est une longue époque, et cela même si nous limitons notre champ de recherche à une partie de cette période seulement, à savoir celle qui voit la littérature en vieux français déjà en pleine floraison : le moyen âge « classique » (le XII e et le XIII e s.) et tardif (le XIV e et le XV e s.). Sur l’espace de quatre siècles, beaucoup de phénomènes littéraires ont eu le temps de naître, évoluer et disparaître dans l’oubli des époques à venir ; d’autres, en passant de leur état primitif vers des formes de plus en plus modernes et éclectiques, ont su se faire une place durable dans la culture universelle. La littérature épique de la France médiévale nous semble appartenir à cette dernière catégorie. Sa résistance au temps nous paraît considérable même si, peu intéressée aux spéculations concernant son existence pendant les « siècles muets » qui ne nous laissent pas de témoins écrits, nous bornons la portée de nos remarques à la période délimitée ci-dessus. Ce genre littéraire a subi certains changements considérables déjà au cours des XII e et XIII e s. ; au niveau formel, les laisses se sont généralement allongées avec le temps, et les procédés typiques de l’épopée de l’âge d’or (parallélismes, similarités, reprises) se sont faits moins fréquents. 1 Quant au contenu, à cause de l’assimilation de certains thèmes romanesques, l’épopée du XIIIe s. -

Legends of the Middle Ages, Narrated with Special Reference to Literature

CORONATION OF CHARLEMAGNE.— L^vy. Legends of the middle ages NARRATED WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO LITERATURE AND ART BY AUTHOR OF "myths OF GREECE AND ROME,'' " MYTHS OF NORTHERN LANDS," "CONTES ET LEGENDES." " Saddle the Hippogriffs, ye Muses nine. And straight ua^U ride to the land ofold Romance.*' WiEI-AND. NEW YORK • : • CINCINNATI • : • CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY Copyright, 1896, by American Book Company. LEGENDS OF THE MIDDLE AGES. B—P2 <J^ DEDICATED TO MY SISTER, ADfiLE E. GUERBER, ;; ; " Men lykyn jestis for to here, And romans rede in diuers manere " Of Brute that baron bold of hond, The first conqueroure of Englond Of kyng Artour that was so riche, Was non in his tyme him Uche. " How kyng CharUs and Rowlond fawght With sarzyns nold they be cawght Of Tristrem and of Ysoude the swete, How tney with love first gan mete; " Stories of diuerce thynggis, Of pryncis, prelatis, and of kynggis Many songgis of diuers ryme, As english, frensh, and latyne." Cursor Mundi. PREFACE. THE object of this work is to familiarize young students with the legends which form the staple of mediaeval literature. While they may owe more than is apparent at first sight to the classical writings of the palmy days of Greece and Rome, these legends are very characteristic of the people who told them, and they are the best exponents of the customs, manners, and beliefs of the time to which they belong. They have been repeated in poetry and prose with endless variations, and some of our greatest modem writers have deemed them worthy of a new dress, as is seen in Tennyson's " Idyls of the King," Goethe's " Reineke Fuchs," Tegn6r's " Frithiof Saga," Wieland's " Oberon," Morris's " Story of Sigurd," and many shorter works by these and less noted writers. -

Rabelais' Pantagruel and Gargantua As Instruction Manuals

FROM POPULAR CULTURE TO ENLIGHTENMENT: RABELAIS’ PANTAGRUEL AND GARGANTUA AS INSTRUCTION MANUALS Ashley Robb A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August: 2012: Committee: Dr. Beatrice Guenther, Advisor Dr. Robert Berg ii ABSTRACT Dr. Beatrice Guenther, Advisor Popular references are a defining feature of François Rabelais’ Pantagruel and Gargantua. One cannot read either of these narratives without being exposed to a barrage of popular characters, imagery, and events. This study serves to elucidate Rabelais’ use of popular characters within Pantagruel and Gargantua by arguing that the author used these characters as instructional tools. The first component of this thesis will analyze the manner in which Rabelais makes use of his mythical protagonists in order to denounce the ideological use of myth. This study will also demonstrate how Rabelais uses popular characters in his second narrative, Gargantua, to evoke Erasmian evangelism. The final chapter of this thesis will examine several narrative techniques employed by Rabelais in order to transmit to his readers lessons on wisdom and truth. The culmination of these examples serves to show how Rabelais’ Pantagruel and Gargantua function as instruction manuals, by redefining and reclaiming what it means to be a Christian, and informing readers how to live a better, more evangelical, life. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. -

Stories of Charlemagne

Conditions and Terms of Use Copyright © Heritage History 2009 Some rights reserved This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an organization dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the promotion of the works of traditional history authors. The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public domain and are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may therefore be reproduced within the United States without paying a royalty to the author. The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, however, are the property of Heritage History and are licensed to individual users with some restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the integrity of the work itself, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure that compromised or incomplete versions of the work are not widely disseminated. In order to preserve information regarding the origin of this text, a copyright by the author, and a Heritage History distribution date are included at the foot of every page of text. We request all electronic and printed versions of this text include these markings and that users adhere to the following restrictions. 1) This text may be reproduced for personal or educational purposes as long as the original copyright and Heritage History version number are faithfully reproduced. 2) You may not alter this text or try to pass off all or any part of it as your own work. 3) You may not distribute copies of this text for commercial purposes unless you have the prior written consent of Heritage History. -

Romance Tradition in Eighteenth-Century Fiction : a Study of Smollett

THE ROMANCE TRADITION IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FICTION: A STUDY OF SMOLLETT By MICHAEL W. RAYMOND COUNCIL OF A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA FOR THE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 197^ ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express heartfelt appreciation to a few of the various multitude who provided incalculable tangible and intangible assistance in bringing this quest to an ordered resolution. Professors Aubrey L. Williams and D. A. Bonneville were most generous, courteous, and dexterous in their assist- ance and encouragement. Their willing contributions in the closing stages of the journey made it less full of "toil and danger" and less "thorny and troublesome." My wife, Judith, was ever present. At once heroine, guide, and Sancho Panza, she bore my short-lived triumphs and enduring despair. She did the work, but I am most grate- ful that she came to understand what the quest meant and what it meant to me. No flights of soaring imagination or extravagant rhetoric can describe adequately my gratitude to Professor Melvyn New. He represents the objective and the signifi- cance of the quest. He always has been the complete scholar and teacher. His contributions to this work have been un- tiring and infinite. More important to me, however, has been and is Professor New's personal example. He embodies the ideal combination of scholar and teacher. Professor Melvyn New shows that the quest for this ideal can be and should be attempted and accomplished. TABLE OE CONTENTS PAGE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ±±± ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 NOTES 15 CHAPTER 1 15 I. -

Sacramental Woes and Theological Anxiety in Medieval Representations of Marriage

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 When Two Become One: Sacramental Woes And Theological Anxiety In Medieval Representations Of Marriage Elizabeth Churchill University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Churchill, Elizabeth, "When Two Become One: Sacramental Woes And Theological Anxiety In Medieval Representations Of Marriage" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2229. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2229 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2229 For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Two Become One: Sacramental Woes And Theological Anxiety In Medieval Representations Of Marriage Abstract This dissertation traces the long, winding, and problematic road along which marriage became a sacrament of the Church. In so doing, it identifies several key problems with marriage’s ability to fulfill the sacramental criteria laid out in Peter Lombard’s Sentences: that a sacrament must signify a specific form of divine grace, and that it must directly bring about the grace that it signifies. While, on the basis of Ephesians 5, theologians had no problem identifying the symbolic power of marriage with the spiritual union of Christ and the Church, they never fully succeeded in locating a form of effective grace, placing immense stress upon marriage’s status as a signifier. As a result, theologians and canonists found themselves unable to deal with several social aspects of marriage that threatened this symbolic capacity, namely concubinage and the remarriage of widows and widowers. -

INSTITUTES of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY THEOLOGY INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles Used by permission from The Westminster Press All Rights Reserved B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 2 JOHN CALVIN: INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION EDITED BY JOHN T. MCNEILL Auburn Professor Emeritus of Church History Union Theological Seminary New York TRANSLATED AND INDEXED BY FORD LEWIS BATTLES Philip Schaff Professor of Church History The Hartford Theological Seminary Hartford, Connecticut in collaboration with the editor and a committee of advisers Philadelphia 3 GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE The Christian Church possesses in its literature an abundant and incomparable treasure. But it is an inheritance that must be reclaimed by each generation. THE LIBRARY OF CHRISTIAN CLASSICS is designed to present in the English language, and in twenty-six volumes of convenient size, a selection of the most indispensable Christian treatises written prior to the end of the sixteenth century. The practice of giving circulation to writings selected for superior worth or special interest was adopted at the beginning of Christian history. The canonical Scriptures were themselves a selection from a much wider literature. In the patristic era there began to appear a class of works of compilation (often designed for ready reference in controversy) of the opinions of well-reputed predecessors, and in the Middle Ages many such works were produced. These medieval anthologies actually preserve some noteworthy materials from works otherwise lost. In modern times, with the increasing inability even of those trained in universities and theological colleges to read Latin and Greek texts with ease and familiarity, the translation of selected portions of earlier Christian literature into modern languages has become more necessary than ever; while the wide range of distinguished books written in vernaculars such as English makes selection there also needful. -

MARGUERITE D'angouleme and the FRENCH LUTHERANS History

In Commemoration of the 400th Anniversary of John Calvin's death, May 27, 1564. MARGUERITE D'ANGOULEME AND THE FRENCH LUTHERANS A STUDY IN PRE-CALVIN REFORMATION IN FRANCE: I DANIEL WALTHER Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan History (which to Paul Val6ry is the most dangerous pro- duct that the chemistry of the intellect has created) must not be subservient to a national cause.l Great minds endeavor to understand andiunite the various trends of history and litera- ture in surrounding nations-Goethe spoke of Welt1iteratu~- but in the latter nineteenth century a chauvinistic nationalism permeated even scholarship. The more one became indepen- dent of foreign ideas and alien influences, the more one thought to be original and creative. The Germany of Fichte sought to discover and defend the national heritage in Germany, and there was a corresponding attitude in the France of Duruy and Augustin Thierry. This nationalistic tendency, fifty years ago, is apparent also among historians of the French Reformation, who endeavored to establish: a) that French Protestantism is autochthonous and organically French, and, b) that the French Reformation came before the German Reformation. Diflering Opinions Among Historians Before 1850, French historians willingly gave Germany credit for the Reformation, as it appeared in the studies of Michelet, who wrote that the "conscience of the times was in Germany" and whose lyrical eulogies of Luther are well known. The same is true of Mignet, Nisard and Merle dJAubig- n6, whose history of the Reformation began to appear in 1835. See a letter by A. Renaudet to L. Febvre, Feb. -

Rabelais and the Abbey of Saint-Victor Revisited Brett Bodemer

4 I&C/Rabelais and the Abbey of Saint-Victor Rabelais and the Abbey of Saint-Victor Revisited Brett Bodemer The seventh chapter of François Rabelais’s Pantagruel concludes with a list of books attributed to the Abbey of Saint-Victor. The chapter’s brief nar rative foregrounds the catalog by touching on aspects of intellectual life in Paris, mentioning both the “great University of Paris” and the “seven liberal arts.” It is not surprising, then, that critics have viewed the catalog as a broad critique of scholasticism. Evidence presented here warrants the addition of a further layer of nuance to this critique that is directly related to this abbey’s contributions to education, reading, textual organization, and library classification. I saw the Library of St. Victor: This most Antient [sic] Convent is the best seated of any in Paris; has very large Gardens, with shady Walks, well kept. The Library is a fair and large Gallery: It is open three days a week, and has a range of double Desks quite through the middle of it, with Seats and Conveniences of Writing for 40 or 50 People. In a part of it, at the upper end, are kept the Manuscripts; they are said to be 3000, which though not very ancient, have yet been found very useful for the most correct Editions of many Authors. This is one of the pleasantest Rooms that can be seen, for the Beauty of its Prospect, and the Quiet and Freedom from Noise in the middle of so great a City. —Martin Lister, A Journey to Paris in the Year 1698 The Englishman Martin Lister published this description of the library of the Abbey of Saint-Victor after his visit to Paris in 1698. -

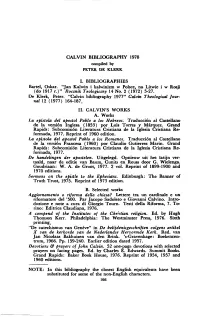

1978 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1978 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Bartel, Oskar. "Jan Kalwin i kalwinizm w Polsce, na Litwie i w Rosji (do 1917 r.)" Rocznik Teologiczny 14 No. 2 (1972) 5-27. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1977" Calvin Theological Jour nal 12 (1977) 164-187. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works La epístola del apóstol Pablo a los Hebreos. Traducción al Castellano de la versión Inglesa (1853) por Luis Torres y Marquez. Grand Rapids: Subcomisión Literatura Cristiana de la Iglesia Cristiana Re formada, 1977. Reprint of 1960 edition. La epístola del apóstol Pablo a los Romanos. Traducción al Castellano de la versión Francesa (1960) por Claudio Gutierrez Marin. Grand Rapids: Subcomisión Literatura Cristiana de la Iglesia Cristiana Re formada, 1977. De handelingen der apostelen. Uitgelegd. Opnieuw uit het latijn ver- taald, naar de editie van Baum, Cunits en Reuss door G. Wielenga. Goudriaan: W. A. de Groot, 1977. 2 vol. Reprint of 1899-1900 and 1970 editions. Sermons on the epistle to the Ephesians. Edinburgh: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1975. Reprint of 1973 edition. B. Selected works Aggiornamento o riforma della chiesa? Lettere tra un cardinale e un riformatore del '500. Par Jacopo Sadoleto e Giovanni Calvino. Intro duzione e note a cura di Giorgio Tourn. Testi della Riforma, 7. To rino: Editrice Claudiana, 1976. A compend of the Institutes of the Christian, religion. Ed. by Hugh Thomson Kerr. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1976. Sixth printing. *'De catechismus van Genève" in De belijdenisgeschriften volgens artikel X van de kerkorde van de Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk. Red. van Jan Nicolaas Bakhuizen van den Brink. -

Renaissance and Reformation, 1974

Translation Theory in Renaissance France: Etienne Dolet and the Rhetorical Tradition Glyn P. Norton The diffusion of vernacularism through translation in late fifteenth and early sixteenth century France is a literary and historical fact well documented in the prefaces of contem- porary works and confirmed by the findings of countless scholars. 1 Well before such ver- nacular apologists as Geoffroy Torv and Joachim Du Bellay, Claude de Seyssel, in a Pro- logue addressed to Louis XII (1509), calls for the founding of a national literature through 2 the medium of translation. By royal decree, Valois monarchs from Francis I to Henry III make glorification of the vernacular a matter of public policy. Translators, as well as gram- marians and poets, are enlisted in a self-conscious national cause, under the "enlightened guidance" of their royal patrons. As theoreticians and apologists begin to seek analogical links between the vernacular idiom and classical languages, translation is seen less and less as a craft of betrayal (conveyed in the Italian proverb "traduttore traditore"). If, indeed, French is capable of the same expressive functions as its classical predecessors, why, people begin to ask, cannot the style and thought of Greece and Rome also be transmitted accu- rately into the vulgar tongue? Not only is translation, then, a means of literary dissemina- tion to the masses, but more vitally, an agent of linguistic illustration. For this reason, translation theory is often inseparably bound to the greater question of how to imitate classical authors in the vernacular idiom. While occasionally taking into account this broader function of translation, scholarly approaches to translation theory in Renaissance France have generally failed to examine these theoretical questions within the framework of cultural change.