Nathan Michalewicz, University of West Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan The relationship between the Ottomans and the Christians did not evolve around continuous hostility and conflict, as is generally assumed. The Ottomans employed Christians extensively, used Western know-how and technology, and en- couraged European merchants to trade in the Levant. On the state level, too, what dictated international diplomacy was not the religious factors, but rather rational strategies that were the results of carefully calculated priorities, for in- stance, several alliances between the Ottomans and the Christian states. All this cooperation blurred the cultural bound- aries and facilitated the flow of people, ideas, technologies and goods from one civilization to another. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Christians in the Service of the Ottomans 3. Ottoman Alliances with the Christian States 4. Conclusion 5. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Citation Introduction Cooperation between the Ottomans and various Christian groups and individuals started as early as the beginning of the 14th century, when the Ottoman state itself emerged. The Ottomans, although a Muslim polity, did not hesitate to cooperate with Christians for practical reasons. Nevertheless, the misreading of the Ghaza (Holy War) literature1 and the consequent romanticization of the Ottomans' struggle in carrying the banner of Islam conceal the true nature of rela- tions between Muslims and Christians. Rather than an inevitable conflict, what prevailed was cooperation in which cul- tural, ethnic, and religious boundaries seemed to disappear. Ÿ1 The Ottomans came into contact and allied themselves with Christians on two levels. Firstly, Christian allies of the Ot- tomans were individuals; the Ottomans employed a number of Christians in their service, mostly, but not always, after they had converted. -

News on the Battle of Petrovaradin and the Siege of Belgrade in the Autobiographical Writings of Jean-Frédéric Diesbach 2

ORIGINAL S CIENTIFIC P APER 355:929 Д ИЗБАХ Ж.-Ф.(093.3) 355.48/.49(436:560)"1716/1718"(093.3) DOI:10.5937/ ZRFFP46-12090 DALIBOR M. E LEZOVIĆ1 UNIVERSITY OF P RIŠTINA WITH TEMPORARY HEAD-OFFICE IN K OSOVSKA M ITROVICA, F ACULTY OF P HILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF H ISTORY NEWS ON THE BATTLE OF PETROVARADIN AND THE SIEGE OF BELGRADE IN THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL WRITINGS OF JEAN-FRÉDÉRIC DIESBACH 2 ABSTRACT. This paper is based on data from the handwritten autobiography of Jean- Frédéric Diesbach, which is kept in the Historical Archives in Fribourg, Switzerland, and in which the Battle of Petrovaradin and the siege of Belgrade are discussed. Diesbach, a Swiss nobleman who was originally in the Swiss and French military service, was later transferred to the Austrian army. This well-known European military leader finished his career as a governor of Syracuse in Sicily and a Major General of the Austrian army. A segment of his memories provides a brief description of the Battle of Petro- varadin and the operations of the Austrian army during the siege of Belgrade. Although it is part of the manuscript of a few pages, it has the value of a historical source, because it is the testimony of participants in these events. KEY WORDS: Battle of Petrovaradin, siege of Belgrade, the Austro-Turkish war, Jean- Frédéric Diesbach. 1 [email protected] 2 The paper presents the results of research conducted under the Project No. III 47023 Kosovo and Me- tohija between national identity and European integration , which is funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia. -

Special List 382: the Ottoman Empire

special list 382 1 RICHARD C.RAMER Special List 382 The Ottoman Empire 2 RICHARDrichard c. C.RAMER ramer Old and Rare Books 225 east 70th street . suite 12f . new york, n.y. 10021-5217 Email [email protected] . Website www.livroraro.com Telephones (212) 737 0222 and 737 0223 Fax (212) 288 4169 July 20, 2020 Special List 382 The Ottoman Empire Items marked with an asterisk (*) will be shipped from Lisbon. SATISFACTION GUARANTEED: All items are understood to be on approval, and may be returned within a reasonable time for any reason whatsoever. VISITORS BY APPOINTMENT Specialspecial Listlist 382 382 3 The Ottoman Empire Procession and Prayers in Mecca to Ward Off the Persians 1. ANTONIO, João Carlos [pseudonym of António Correia de Lemos]. Relaçam de huma solemne e extraordinaria procissam de preces, que por ordem da Corte Ottomana fizerão os Turcos na Cidade de Meca, no dia 16 de Julho de 1728. Para alcançar a assistencia de Deos contra as armas dos Persas; e aplacar o flagello da peste, que todos os annos experimenta a sua Monarquia. Traduzida de huma que se recebeo da Cidade de Constanti- nopla por ... Primeira parte [only, of 2]. Lisboa Occidental: Na Officina de Pedro Ferreira, 1730. 4°, disbound. Small woodcut vignette on title page. Woodcut headpiece with arms of Portugal and five-line woodcut initial on p. 3. Minor marginal worming (touching a few letters at edges), light browning, lower margin unevenly cut but not touching text. Barely in good condition. 21, (2) pp. $700.00 First Edition in Portuguese, with a lengthy and detailed description of a procession at Mecca. -

Ottoman Corsairs in the Central Mediterranean and the Slave Trade in the 16Th Century

SAĠM ANIL KARZEK ANIL SAĠM MEDITERRANEAN AND THE SLAVE TRADE SLAVE AND THE IN MEDITERRANEAN OTTOMAN CORSAIRS IN THE CENTRAL CORSAIRS THE IN OTTOMAN OTTOMAN CORSAIRS IN THE CENTRAL THE 16TH 16TH THE MEDITERRANEAN AND THE SLAVE TRADE IN THE 16TH CENTURY CENTURY A Master‟s Thesis by SAĠM ANIL KARZEK Department of History Ġhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara Bilkent 2021 University August 2021 To my beloved family OTTOMAN CORSAIRS IN THE CENTRAL MEDITERRANEAN AND THE SLAVE TRADE IN THE 16TH CENTURY The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of Ġhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by SAĠM ANIL KARZEK In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HISTORY THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ĠHSAN DOĞRAMACI BĠLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of History. Prof. Dr. Özer Ergenç Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of History. I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of History Prof. Dr. Mehmet Veli Seyitdanlıoğlu Examining Committee Member Approval of the Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Refet Soykan Gürkaynak Director ABSTRACT OTTOMAN CORSAIRS IN THE CENTRAL MEDITERRANEAN AND THE SLAVE TRADE IN THE 16TH CENTURY Karzek, Saim Anıl M.A., Department of History Supervisor: Özer Ergenç August 2021 This thesis aims to analyze the Ottoman corsairs and their role in the slave trade in the 16th century Mediterranean, and it concentrates on the corsair activity around the central Mediterranean during Suleiman I's reign. -

INSTITUTES of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY THEOLOGY INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles Used by permission from The Westminster Press All Rights Reserved B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 2 JOHN CALVIN: INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION EDITED BY JOHN T. MCNEILL Auburn Professor Emeritus of Church History Union Theological Seminary New York TRANSLATED AND INDEXED BY FORD LEWIS BATTLES Philip Schaff Professor of Church History The Hartford Theological Seminary Hartford, Connecticut in collaboration with the editor and a committee of advisers Philadelphia 3 GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE The Christian Church possesses in its literature an abundant and incomparable treasure. But it is an inheritance that must be reclaimed by each generation. THE LIBRARY OF CHRISTIAN CLASSICS is designed to present in the English language, and in twenty-six volumes of convenient size, a selection of the most indispensable Christian treatises written prior to the end of the sixteenth century. The practice of giving circulation to writings selected for superior worth or special interest was adopted at the beginning of Christian history. The canonical Scriptures were themselves a selection from a much wider literature. In the patristic era there began to appear a class of works of compilation (often designed for ready reference in controversy) of the opinions of well-reputed predecessors, and in the Middle Ages many such works were produced. These medieval anthologies actually preserve some noteworthy materials from works otherwise lost. In modern times, with the increasing inability even of those trained in universities and theological colleges to read Latin and Greek texts with ease and familiarity, the translation of selected portions of earlier Christian literature into modern languages has become more necessary than ever; while the wide range of distinguished books written in vernaculars such as English makes selection there also needful. -

MARGUERITE D'angouleme and the FRENCH LUTHERANS History

In Commemoration of the 400th Anniversary of John Calvin's death, May 27, 1564. MARGUERITE D'ANGOULEME AND THE FRENCH LUTHERANS A STUDY IN PRE-CALVIN REFORMATION IN FRANCE: I DANIEL WALTHER Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan History (which to Paul Val6ry is the most dangerous pro- duct that the chemistry of the intellect has created) must not be subservient to a national cause.l Great minds endeavor to understand andiunite the various trends of history and litera- ture in surrounding nations-Goethe spoke of Welt1iteratu~- but in the latter nineteenth century a chauvinistic nationalism permeated even scholarship. The more one became indepen- dent of foreign ideas and alien influences, the more one thought to be original and creative. The Germany of Fichte sought to discover and defend the national heritage in Germany, and there was a corresponding attitude in the France of Duruy and Augustin Thierry. This nationalistic tendency, fifty years ago, is apparent also among historians of the French Reformation, who endeavored to establish: a) that French Protestantism is autochthonous and organically French, and, b) that the French Reformation came before the German Reformation. Diflering Opinions Among Historians Before 1850, French historians willingly gave Germany credit for the Reformation, as it appeared in the studies of Michelet, who wrote that the "conscience of the times was in Germany" and whose lyrical eulogies of Luther are well known. The same is true of Mignet, Nisard and Merle dJAubig- n6, whose history of the Reformation began to appear in 1835. See a letter by A. Renaudet to L. Febvre, Feb. -

Pantagruel and Gargantua

Pantagruel and Gargantua Pantagruel and Gargantua François Rabelais Translated by Andrew Brown ALMA CLASSICS alma classics an imprint of alma books ltd 3 Castle Yard Richmond Surrey TW10 6TF United Kingdom www.almaclassics.com Pantagruel first published in French in 1532 Gargantua first published in French in 1534 This translation first published by Hesperus Press Ltd in 2003 This revised version first published by Alma Classics in 2018 Translation, Introduction and Notes © Andrew Brown 2003, 2018 Cover design: nathanburtondesign.com Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY isbn: 978-1-84749-740-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Introduction vii Pantagruel 1 Gargantua 135 Note on the Text 301 Notes 301 Introduction On 3rd August 1546 (his birthday: he was thirty-seven years old), Étienne Dolet, the great Humanist poet, philologist, publisher and translator, having been tortured, was taken out to the Place Maubert in Paris, within sight of Notre-Dame. Here, he was strangled and burnt. Copies of his books accompanied him to the flames. His crime? Greek. More specifically, he had been found guilty of producing and publishing a translation from Plato which attributed to Socrates the heretical words “After death you will be nothing at all (plus rien du tout)”. -

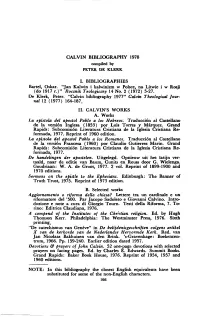

1978 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1978 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Bartel, Oskar. "Jan Kalwin i kalwinizm w Polsce, na Litwie i w Rosji (do 1917 r.)" Rocznik Teologiczny 14 No. 2 (1972) 5-27. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1977" Calvin Theological Jour nal 12 (1977) 164-187. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works La epístola del apóstol Pablo a los Hebreos. Traducción al Castellano de la versión Inglesa (1853) por Luis Torres y Marquez. Grand Rapids: Subcomisión Literatura Cristiana de la Iglesia Cristiana Re formada, 1977. Reprint of 1960 edition. La epístola del apóstol Pablo a los Romanos. Traducción al Castellano de la versión Francesa (1960) por Claudio Gutierrez Marin. Grand Rapids: Subcomisión Literatura Cristiana de la Iglesia Cristiana Re formada, 1977. De handelingen der apostelen. Uitgelegd. Opnieuw uit het latijn ver- taald, naar de editie van Baum, Cunits en Reuss door G. Wielenga. Goudriaan: W. A. de Groot, 1977. 2 vol. Reprint of 1899-1900 and 1970 editions. Sermons on the epistle to the Ephesians. Edinburgh: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1975. Reprint of 1973 edition. B. Selected works Aggiornamento o riforma della chiesa? Lettere tra un cardinale e un riformatore del '500. Par Jacopo Sadoleto e Giovanni Calvino. Intro duzione e note a cura di Giorgio Tourn. Testi della Riforma, 7. To rino: Editrice Claudiana, 1976. A compend of the Institutes of the Christian, religion. Ed. by Hugh Thomson Kerr. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1976. Sixth printing. *'De catechismus van Genève" in De belijdenisgeschriften volgens artikel X van de kerkorde van de Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk. Red. van Jan Nicolaas Bakhuizen van den Brink. -

Renaissance and Reformation, 1974

Translation Theory in Renaissance France: Etienne Dolet and the Rhetorical Tradition Glyn P. Norton The diffusion of vernacularism through translation in late fifteenth and early sixteenth century France is a literary and historical fact well documented in the prefaces of contem- porary works and confirmed by the findings of countless scholars. 1 Well before such ver- nacular apologists as Geoffroy Torv and Joachim Du Bellay, Claude de Seyssel, in a Pro- logue addressed to Louis XII (1509), calls for the founding of a national literature through 2 the medium of translation. By royal decree, Valois monarchs from Francis I to Henry III make glorification of the vernacular a matter of public policy. Translators, as well as gram- marians and poets, are enlisted in a self-conscious national cause, under the "enlightened guidance" of their royal patrons. As theoreticians and apologists begin to seek analogical links between the vernacular idiom and classical languages, translation is seen less and less as a craft of betrayal (conveyed in the Italian proverb "traduttore traditore"). If, indeed, French is capable of the same expressive functions as its classical predecessors, why, people begin to ask, cannot the style and thought of Greece and Rome also be transmitted accu- rately into the vulgar tongue? Not only is translation, then, a means of literary dissemina- tion to the masses, but more vitally, an agent of linguistic illustration. For this reason, translation theory is often inseparably bound to the greater question of how to imitate classical authors in the vernacular idiom. While occasionally taking into account this broader function of translation, scholarly approaches to translation theory in Renaissance France have generally failed to examine these theoretical questions within the framework of cultural change. -

A Legal and Historical Study of Latin Catholic Church Properties in Istanbul from the Ottoman Conquest of 1453 Until 1740

AIX-MARSEILLE UNIVERSITE ******** THESIS To obtain the grade of DOCTOR OF AIX-MARSEILLE UNIVERSITY Doctoral College N° 355: Espaces, Cultures, Sociétés Presented and defended publically by Vanessa R. DE OBALDÍA 18 December 2018 TITLE A Legal and Historical Study of Latin Catholic Church Properties in Istanbul from the Ottoman Conquest of 1453 until 1740 Thesis supervisor: Randi DEGUILHEM Jury AKARLI Engin, emeritus professor, İstanbul Şehir University BORROMEO Elisabetta, Ingénieur d’Études, CNRS, Collège de France, Paris DEGUILHEM Randi, Directrice de Recherche, CNRS, TELEMMe-MMSH, Aix- Marseille University, Aix-en-Provence GHOBRIAL John-Paul, associate professor, University of Oxford GRADEVA Rossitsa, professor, American University of Bulgaria, rapporteure SERMET Laurent, professor, Institut d’Études Politiques, Aix-en-Provence TOLAN John, professor, University of Nantes, rapporteur To my mother for all her support and loving care. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i ABSTRACT ii INTRODUCTION iv PART I: The legal status of Roman Catholics and their Religious Orders in Ottoman Istanbul 1. Introduction 1 2. Galata and Pera 1 a. Galata 1 b. Pera 5 3. The demographic composition of Roman Catholics in Galata & Pera 8 4. The legal status of Roman Catholics in Constantinople/Istanbul 15 a. Pre-conquest - Catholics as a semi-autonomous colony 15 b. Post-conquest - Catholics as zimmīs 16 5. The legal status of Latin Catholic religious orders 20 a. According to Ottoman law 20 b. Compared to the status of Orthodox and Armenian churches and Jews 25 in the capital 6. The representatives of Latin Catholic churches and ecclesiastical properties 35 a. La Magnifica Comunità di Pera 35 b. La Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide 40 c. -

Ottoman Expansionist Policy in the Sixteenth Century Mediterranean

OTTOMAN EXPANSIONIST POLICY IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY MEDITERRANEAN OTTOMAN EXPANSIONIST POLICY IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY MEDITERRANEAN CARMEL CASSAR THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY Mediterranean has often been described as ‘a battleground’ between the two great empires of Catholic Spain in the West and the Muslim Ottomans in the East. It was a century during which the two great empires gave evidence of their formidable might. Before the rise of the Habsburg kings, Charles V and Philip II, the Catholic Kings of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, who were responsible for the unification of Spain, played as vital a part in creating the Spanish Empire as did the Ottoman sultans before the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The Political Scene in the Early Sixteenth Century Mediterranean The union of the Kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, and the conquest of Granada in 1492 - the last Muslim stronghold on mainland Spain - did more than just unify Spain. It led to the creation of a union of two strong kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula which, apart from helping to generate a religious revival throughout the peninsula, also boosted exploratory navigation that led to a surge of colonisation that helped to transform Spain into a global empire. On the one hand, the Castilians were mainly centred on the Americas. Colonization and territorial expansion was coupled with an economic policy meant to exploit to the maximum the commercial value of the newly-conquered lands. On the other hand, Aragon centred on the Mediterranean. It had long been acquainted with the sea through her shipping. Aragon possessed islands like the Balearics, Sardinia and Sicily, and was committed to checking the 83 BESIEGED: MALTA 1565 advance of Islam in the Western Mediterranean. -

Marguerite De Navarre's Heptaméron,François Rabelais's

136 Book Reviews Marguerite de Navarre’s Heptaméron, François Rabelais’s Quart Livre, and narratives by Bonaventure Des Périers, Noël Du Fail and Jacques Yver. As the subtitle suggests, the link between material culture and evangelical spirituality in the Heptaméron is the main focus of much of the book. Drawing parallels between the composition of early modern art (Northern European painting in particular), decorative styles, narrative fi ction, and evangel- ical teachings such as Luther’s Table Talk, Catherine Randall posits that there was paradigm shift from an allegorical understanding of the world to a more subjective, metaphorical relation to objects. According to her, the evangelical ambivalence toward commodity culture was expressed in a distrust of materiality: objects and images were desacralized, but could be used to point the way to salvation. Indeed, not only are material objects seen to be re-oriented toward the metaphysical in evangelical narrative, but plain style is preferred to ornament, and storytelling and the nouvelle genre in particular are seen as part of sharing the bonne nouvelle or “good news” of the gospel. Th e idea of analyzing material culture in Marguerite de Navarre’s Heptaméron is fascinating and original, as is the notion that the work can be read as an evangelical narrative. Indeed, the close reading of nouvelles represents the most compelling parts of this study (though there is occasional confusion between tales in the Heptaméron, including some distracting numbering issues). Th e earlier sections on the visual arts are less nuanced and persuasive, leading one to wonder, in part, how much of what is interpreted as reformist aesthetics can be att ributed to other factors.