2 Calvin's Institutes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INSTITUTES of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY THEOLOGY INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles Used by permission from The Westminster Press All Rights Reserved B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 2 JOHN CALVIN: INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION EDITED BY JOHN T. MCNEILL Auburn Professor Emeritus of Church History Union Theological Seminary New York TRANSLATED AND INDEXED BY FORD LEWIS BATTLES Philip Schaff Professor of Church History The Hartford Theological Seminary Hartford, Connecticut in collaboration with the editor and a committee of advisers Philadelphia 3 GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE The Christian Church possesses in its literature an abundant and incomparable treasure. But it is an inheritance that must be reclaimed by each generation. THE LIBRARY OF CHRISTIAN CLASSICS is designed to present in the English language, and in twenty-six volumes of convenient size, a selection of the most indispensable Christian treatises written prior to the end of the sixteenth century. The practice of giving circulation to writings selected for superior worth or special interest was adopted at the beginning of Christian history. The canonical Scriptures were themselves a selection from a much wider literature. In the patristic era there began to appear a class of works of compilation (often designed for ready reference in controversy) of the opinions of well-reputed predecessors, and in the Middle Ages many such works were produced. These medieval anthologies actually preserve some noteworthy materials from works otherwise lost. In modern times, with the increasing inability even of those trained in universities and theological colleges to read Latin and Greek texts with ease and familiarity, the translation of selected portions of earlier Christian literature into modern languages has become more necessary than ever; while the wide range of distinguished books written in vernaculars such as English makes selection there also needful. -

MARGUERITE D'angouleme and the FRENCH LUTHERANS History

In Commemoration of the 400th Anniversary of John Calvin's death, May 27, 1564. MARGUERITE D'ANGOULEME AND THE FRENCH LUTHERANS A STUDY IN PRE-CALVIN REFORMATION IN FRANCE: I DANIEL WALTHER Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan History (which to Paul Val6ry is the most dangerous pro- duct that the chemistry of the intellect has created) must not be subservient to a national cause.l Great minds endeavor to understand andiunite the various trends of history and litera- ture in surrounding nations-Goethe spoke of Welt1iteratu~- but in the latter nineteenth century a chauvinistic nationalism permeated even scholarship. The more one became indepen- dent of foreign ideas and alien influences, the more one thought to be original and creative. The Germany of Fichte sought to discover and defend the national heritage in Germany, and there was a corresponding attitude in the France of Duruy and Augustin Thierry. This nationalistic tendency, fifty years ago, is apparent also among historians of the French Reformation, who endeavored to establish: a) that French Protestantism is autochthonous and organically French, and, b) that the French Reformation came before the German Reformation. Diflering Opinions Among Historians Before 1850, French historians willingly gave Germany credit for the Reformation, as it appeared in the studies of Michelet, who wrote that the "conscience of the times was in Germany" and whose lyrical eulogies of Luther are well known. The same is true of Mignet, Nisard and Merle dJAubig- n6, whose history of the Reformation began to appear in 1835. See a letter by A. Renaudet to L. Febvre, Feb. -

Pantagruel and Gargantua

Pantagruel and Gargantua Pantagruel and Gargantua François Rabelais Translated by Andrew Brown ALMA CLASSICS alma classics an imprint of alma books ltd 3 Castle Yard Richmond Surrey TW10 6TF United Kingdom www.almaclassics.com Pantagruel first published in French in 1532 Gargantua first published in French in 1534 This translation first published by Hesperus Press Ltd in 2003 This revised version first published by Alma Classics in 2018 Translation, Introduction and Notes © Andrew Brown 2003, 2018 Cover design: nathanburtondesign.com Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY isbn: 978-1-84749-740-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Introduction vii Pantagruel 1 Gargantua 135 Note on the Text 301 Notes 301 Introduction On 3rd August 1546 (his birthday: he was thirty-seven years old), Étienne Dolet, the great Humanist poet, philologist, publisher and translator, having been tortured, was taken out to the Place Maubert in Paris, within sight of Notre-Dame. Here, he was strangled and burnt. Copies of his books accompanied him to the flames. His crime? Greek. More specifically, he had been found guilty of producing and publishing a translation from Plato which attributed to Socrates the heretical words “After death you will be nothing at all (plus rien du tout)”. -

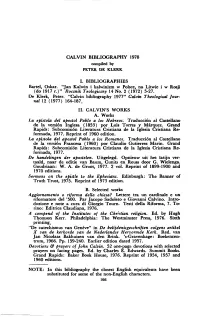

1978 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1978 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Bartel, Oskar. "Jan Kalwin i kalwinizm w Polsce, na Litwie i w Rosji (do 1917 r.)" Rocznik Teologiczny 14 No. 2 (1972) 5-27. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1977" Calvin Theological Jour nal 12 (1977) 164-187. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works La epístola del apóstol Pablo a los Hebreos. Traducción al Castellano de la versión Inglesa (1853) por Luis Torres y Marquez. Grand Rapids: Subcomisión Literatura Cristiana de la Iglesia Cristiana Re formada, 1977. Reprint of 1960 edition. La epístola del apóstol Pablo a los Romanos. Traducción al Castellano de la versión Francesa (1960) por Claudio Gutierrez Marin. Grand Rapids: Subcomisión Literatura Cristiana de la Iglesia Cristiana Re formada, 1977. De handelingen der apostelen. Uitgelegd. Opnieuw uit het latijn ver- taald, naar de editie van Baum, Cunits en Reuss door G. Wielenga. Goudriaan: W. A. de Groot, 1977. 2 vol. Reprint of 1899-1900 and 1970 editions. Sermons on the epistle to the Ephesians. Edinburgh: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1975. Reprint of 1973 edition. B. Selected works Aggiornamento o riforma della chiesa? Lettere tra un cardinale e un riformatore del '500. Par Jacopo Sadoleto e Giovanni Calvino. Intro duzione e note a cura di Giorgio Tourn. Testi della Riforma, 7. To rino: Editrice Claudiana, 1976. A compend of the Institutes of the Christian, religion. Ed. by Hugh Thomson Kerr. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1976. Sixth printing. *'De catechismus van Genève" in De belijdenisgeschriften volgens artikel X van de kerkorde van de Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk. Red. van Jan Nicolaas Bakhuizen van den Brink. -

Renaissance and Reformation, 1974

Translation Theory in Renaissance France: Etienne Dolet and the Rhetorical Tradition Glyn P. Norton The diffusion of vernacularism through translation in late fifteenth and early sixteenth century France is a literary and historical fact well documented in the prefaces of contem- porary works and confirmed by the findings of countless scholars. 1 Well before such ver- nacular apologists as Geoffroy Torv and Joachim Du Bellay, Claude de Seyssel, in a Pro- logue addressed to Louis XII (1509), calls for the founding of a national literature through 2 the medium of translation. By royal decree, Valois monarchs from Francis I to Henry III make glorification of the vernacular a matter of public policy. Translators, as well as gram- marians and poets, are enlisted in a self-conscious national cause, under the "enlightened guidance" of their royal patrons. As theoreticians and apologists begin to seek analogical links between the vernacular idiom and classical languages, translation is seen less and less as a craft of betrayal (conveyed in the Italian proverb "traduttore traditore"). If, indeed, French is capable of the same expressive functions as its classical predecessors, why, people begin to ask, cannot the style and thought of Greece and Rome also be transmitted accu- rately into the vulgar tongue? Not only is translation, then, a means of literary dissemina- tion to the masses, but more vitally, an agent of linguistic illustration. For this reason, translation theory is often inseparably bound to the greater question of how to imitate classical authors in the vernacular idiom. While occasionally taking into account this broader function of translation, scholarly approaches to translation theory in Renaissance France have generally failed to examine these theoretical questions within the framework of cultural change. -

Marguerite De Navarre's Heptaméron,François Rabelais's

136 Book Reviews Marguerite de Navarre’s Heptaméron, François Rabelais’s Quart Livre, and narratives by Bonaventure Des Périers, Noël Du Fail and Jacques Yver. As the subtitle suggests, the link between material culture and evangelical spirituality in the Heptaméron is the main focus of much of the book. Drawing parallels between the composition of early modern art (Northern European painting in particular), decorative styles, narrative fi ction, and evangel- ical teachings such as Luther’s Table Talk, Catherine Randall posits that there was paradigm shift from an allegorical understanding of the world to a more subjective, metaphorical relation to objects. According to her, the evangelical ambivalence toward commodity culture was expressed in a distrust of materiality: objects and images were desacralized, but could be used to point the way to salvation. Indeed, not only are material objects seen to be re-oriented toward the metaphysical in evangelical narrative, but plain style is preferred to ornament, and storytelling and the nouvelle genre in particular are seen as part of sharing the bonne nouvelle or “good news” of the gospel. Th e idea of analyzing material culture in Marguerite de Navarre’s Heptaméron is fascinating and original, as is the notion that the work can be read as an evangelical narrative. Indeed, the close reading of nouvelles represents the most compelling parts of this study (though there is occasional confusion between tales in the Heptaméron, including some distracting numbering issues). Th e earlier sections on the visual arts are less nuanced and persuasive, leading one to wonder, in part, how much of what is interpreted as reformist aesthetics can be att ributed to other factors. -

Dr. François Rabelais

Dr. FRANgOIS RABELAIS. H. S. CARTER, M.D., D.P.H. People who use the word Rabelaisian as readily as they would Shakes- pearean or Dickensian seldom know anything about Francois Rabelais and his amazing works. Vaguely they think of his writings as something hardly fit for the light of day, to be sought for furtively in the dark corners ?f antiquarian book-shops. And it is true that these writings are dis- figured here and there by scatological lines and verses and by obscenities resembling those graffiti to be seen scrawled on the walls of public places ; but always in the most overt and jolly manner. So the author is visua- lized as a gross buffoon of the later middle ages whose legacy to humanity a large collection of tap-room anecdotes and smoke-room stories related ' with Bacchic exuberance, rather than one who plumbed the true Well and Abyss of encyclopaedic learning ', and gave a valuable reflection ?f the sentiment and character of his time. The humour of Rabelais is ' not in his occasional indecency. Lord Bacon called Rabelais the Grand ' Jester of France ', but Coleridge wrote beyond a doubt Rabelais was among the deepest as well as the boldest thinkers of his age', and classed him with the great creative minds, Shakespeare, Dante, Cervantes. He lived during the years of transition from the Middle Ages to the early Renaissance, and reflected the outlook of more enlightened men, their thirst for knowledge and their impatience with the suppressions and restrict- tions which had long shackled the activities of the human mind. -

Nathan Michalewicz, University of West Georgia

François de Beaucaire de Péguillon and the Ottoman Empire: Perceptions of a Sixteenth-Century Militant Bishop Nathan Michalewicz, University of West Georgia In 1568, a French ecclesiastic closely connected to the Guise and the ultra- Catholic faction set out to write a history of France of the past one hundred years. After twenty years of work, the author, François de Beaucaire de Péguillon, finished the Rerum gallicarum commentarii (Notes of French Affairs), which he described in the subtitle as An Historical Treatise Drawn from the Opportunity and Various Places of Italy, Germany, Spain, Hungary, and Turkey.1 As such a description would suggest, the Ottoman Empire loomed large on the European continent in the Commentarii, and Beaucaire paid significant attention to the Islamic Empire and its alliance with France throughout the work. Indeed, the Ottomans receive almost as much attention as Charles V. Yet, Beaucaire’s views of France’s Muslim ally remain uninvestigated. Traditionally, historians have drawn a strict division between the Ottoman Empire and Christian Europe. These scholars, however, have come to this same general conclusion through one of two ways. Some assert the primacy of cultural differences; others, religious distinctions. Nonetheless, the traditional narrative asserts that Europeans saw the Ottomans as wholly other.2 For instance, one 1 Francisco Belcario Peguilione, Rerum gallicarum commentarii accessit ex occasione, variis locis, Italicae, Germanicae, Hispanicae, & Turcicae historiae tractatio (Lyon: Claudii Landry, 1625); Albert Lesmaris, Un Historien du XVIe siècle: François de Beaucaire de Puyguillon, 1514-1591, sa vie, ses écrtis, sa famille (Clermont-Ferrand: G. de Bussac, 1958). All of the translations contained in this paper are my own unless otherwise indicated. -

INFORMATION to USERS Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This materia was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most atfraneed technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been ured the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or Mttems which may appear on this reproduction. I.T he sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sretioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of 8 large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, ^wever, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from lotographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

A Bilingual Edition and Study Kelly Digby Peebles Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints Publications Languages 8-2014 Tales and Trials of Love: a Bilingual Edition and Study Kelly Digby Peebles Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/languages_pubs Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Please use publisher's recommended citation. This Book Contribution is brought to you for free and open access by the Languages at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction The Other Voice KELLY DIGBY PEEBLES What we know about Jeanne Flore, if indeed there was a Jeanne Flore, we glean solely from her printed works, a total of seven tales, each introduced and narrated by a female storyteller. Despite its relative- ly small volume, Jeanne Flore’s body of work significantly elucidates important questions about women’s status and roles in the culture of Renaissance France, particularly in the city of Lyon. Jeanne Flore’s con- temporaries Pernette du Guillet and Louise Labé also lived in Lyon; each had a volume of poetry printed in her name, and prominent male authors dedicated poems to both women in praise of their beauty and learning. Some thirty years after Comptes amoureux was first pub- lished, the Dames des Roches would host a literary coterie in Poitiers, publish both poetry and prose, and gain the recognition of noted male and female intellectuals.1 Unlike these women, we have no written re- cord of Jeanne Flore aside from her two published works.2 We do not know who this author was. -

Le Cymbalum Mundi De Bonaventure Des Périers: La Difficile Interprétation D’Un Recueil Humaniste

Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Academiejaar 2006-2007 Esther Kestemont Le Cymbalum Mundi de Bonaventure Des Périers: la difficile interprétation d’un recueil humaniste Promotor : Dr. Alexander Roose Verhandeling voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte tot het behalen van de graad licentiaat in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Romaanse Talen Remerciements Ecrire le mémoire est le dernier stade à franchir avant d‟obtenir le diplôme. Après les quatre Ŕ pour certains d‟entre nous même plus de quatre Ŕ années d‟étude, ce travail en est le couronnement. Or, le résultat final, que vous détenez à ce moment, n‟aurait pas pu se réaliser sans l‟aide de certaines personnes. Tout d‟abord, mes remerciements les plus reconnaissants vont à Dr. Alexander Roose. Outre son enthousiasme et son encouragement, qui ne peuvent que produire un effet contagieux, je le remercie de sa disponibilité ainsi que de ses conseils constructifs. Ma gratitude va aussi à ma famille, surtout à mes parents. Ils m‟ont non seulement donné la possibilité d‟entamer des études universitaires, mais ils m‟ont soutenue du début à la fin. En dernier lieu, je tiens à remercier mon ami, Frank Ketels. Il n‟est pas facile de participer à la besogne d‟une personne en train d‟écrire son mémoire. Je le remercie pour avoir assumé les soins du ménage, pour son aide Ŕ surtout à propos de l‟aspect technique du mémoire Ŕ et pour son soutien perpétuel. Table des matières 1. Introduction ………………………………………………….……………….. p. 1 2. Préface historique ……………………………………………….….……….. p. 4 2.1 Le XVIe siècle …………………………………...…….……………... p. 4 2.2 Bonaventure Des Périers ……….……………..……………….… p. -

A TRANSGENERATIONAL, CRYPTONOMIC, and SOCIOMETERIC ANALYSIS of MARGUERITE DE NAVARRE's HEPTAMERON by Kathleen M. Bradley

A Transgenerational, Cryptonymy, and Sociometeric Analysis of Marguerite de Navarre's Heptameron Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Bradley, Kathleen Marie Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 16:50:35 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195091 1 A TRANSGENERATIONAL, CRYPTONOMIC, AND SOCIOMETERIC ANALYSIS OF MARGUERITE DE NAVARRE’S HEPTAMERON by Kathleen M. Bradley ______________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH AND ITALIAN In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN FRENCH In the Graduate College 2007 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Kathleen M. Bradley entitled A Transgenerational, Cryptonomic, and Sociometric Analysis of Marguerite de Navarre's Heptameron and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ Date: May 3, 2007 Elizabeth Chesney Zegura ________________________________________ Date: May 3, 2007 Jonathan Beck ________________________________________ Date: May 3, 2007 Lise Leibacher Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final corrected copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement.