INFORMATION to USERS Xerox University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antoine De Chandieu (1534-1591): One of the Fathers Of

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): ONE OF THE FATHERS OF REFORMED SCHOLASTICISM? A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2013 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan • 49546-4301 800388-6034 fax: 616 957-8621 [email protected] www. calvinseminary. edu. This dissertation entitled ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): L'UN DES PERES DE LA SCHOLASTIQUE REFORMEE? written by THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: Richard A. Muller, Ph.D. I Date ~ 4 ,,?tJ/3 Dean of Academic Programs Copyright © 2013 by Theodore G. (Ted) Van Raalte All rights reserved For Christine CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ................................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1 Introduction: Historiography and Scholastic Method Introduction .............................................................................................................1 State of Research on Chandieu ...............................................................................6 Published Research on Chandieu’s Contemporary -

Albret, Jean D' Entries Châlons-En-Champagne (1487)

Index Abbeville 113, 182 Albret, Jean d’ Entries Entries Charles de Bourbon (1520) 183 Châlons-en-Champagne (1487) 181 Charles VIII (1493) 26–27, 35, 41, Albret, Jeanne d’ 50–51, 81, 97, 112 Entries Eleanor of Austria (1531) 60, 139, Limoges (1556) 202 148n64, 160–61 Alençon, Charles, duke of (d.1525) 186, Henry VI (1430) 136 188–89 Louis XI (1463) 53, 86n43, 97n90 Almanni, Luigi 109 Repurchased by Louis XI (1463) 53 Altars 43, 44 Abigail, wife of King David 96 Ambassadors 9–10, 76, 97, 146, 156 Albon de Saint André, Jean d’ 134 Amboise 135, 154 Entries Amboise, Edict of (1563) 67 Lyon (1550) 192, 197, 198–99, 201, 209, Amboise, Georges d’, cardinal and archbishop 214 of Rouen (d.1510) 64–65, 130, 194 Abraham 96 Entries Accounts, financial 15, 16 Noyon (1508) 204 Aeneas 107 Paris (1502) 194 Agamemnon 108 Saint-Quentin (1508) 204 Agen Amelot, Jacques-Charles 218 Entries Amiens 143, 182 Catherine de Medici (1578) 171 Bishop of Charles IX (1565) 125–26, 151–52 Entries Governors 183–84 Nicholas de Pellevé (1555) 28 Oath to Louis XI 185 Captain of 120 Preparing entry for Francis I (1542) 79 Claubaut family 91 Agricol, Saint 184 Confirmation of liberties at court 44, Aire-sur-la-Lys 225 63–64 Aix-en-Provence Entries Confirmation of liberties at court 63n156 Anne of Beaujeu (1493) 105, 175 Entries Antoine de Bourbon (1541) 143, 192, Charles IX (1564) 66n167 209 Bernard de Nogaret de La Valette (1587) Charles VI and Dauphin Louis (1414) 196n79 97n90, 139, 211n164 Françoise de Foix-Candale (1547) Léonor dʼOrléans, duke of Longueville 213–14 (1571) -

Charles V, Monarchia Universalis and the Law of Nations (1515-1530)

+(,121/,1( Citation: 71 Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis 79 2003 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Mon Jan 30 03:58:51 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information CHARLES V, MONARCHIA UNIVERSALIS AND THE LAW OF NATIONS (1515-1530) by RANDALL LESAFFER (Tilburg and Leuven)* Introduction Nowadays most international legal historians agree that the first half of the sixteenth century - coinciding with the life of the emperor Charles V (1500- 1558) - marked the collapse of the medieval European order and the very first origins of the modem state system'. Though it took to the end of the seven- teenth century for the modem law of nations, based on the idea of state sover- eignty, to be formed, the roots of many of its concepts and institutions can be situated in this period2 . While all this might be true in retrospect, it would be by far overstretching the point to state that the victory of the emerging sovereign state over the medieval system was a foregone conclusion for the politicians and lawyers of * I am greatly indebted to professor James Crawford (Cambridge), professor Karl- Heinz Ziegler (Hamburg) and Mrs. Norah Engmann-Gallagher for their comments and suggestions, as well as to the board and staff of the Lauterpacht Research Centre for Inter- national Law at the University of Cambridge for their hospitality during the period I worked there on this article. -

Scenario Book 1

Here I Stand SCENARIO BOOK 1 SCENARIO BOOK T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S ABOUT THIS BOOK ......................................................... 2 Controlling 2 Powers ........................................................... 6 GETTING STARTED ......................................................... 2 Domination Victory ............................................................. 6 SCENARIOS ....................................................................... 2 PLAY-BY-EMAIL TIPS ...................................................... 6 Setup Guidelines .................................................................. 2 Interruptions to Play ............................................................ 6 1517 Scenario ...................................................................... 3 Response Card Play ............................................................. 7 1532 Scenario ...................................................................... 4 DESIGNER’S NOTES ........................................................ 7 Tournament Scenario ........................................................... 5 EXTENDED EXAMPLE OF PLAY................................... 8 SETTING YOUR OWN TIME LIMIT ............................... 6 THE GAME AS HISTORY................................................. 11 GAMES WITH 3 TO 5 PLAYERS ..................................... 6 CHARACTERS OF THE REFORMATION ...................... 15 Configurations ..................................................................... 6 EVENTS OF THE REFORMATION -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

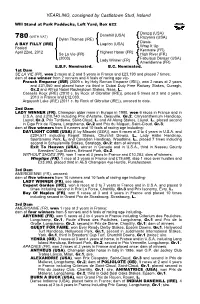

YEARLING, Consigned by Castletown Stud, Ireland

YEARLING, consigned by Castletown Stud, Ireland Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Left Yard, Box 622 Danzig (USA) Danehill (USA) 780 (WITH VAT) Razyana (USA) Dylan Thomas (IRE) Diesis Lagrion (USA) A BAY FILLY (IRE) Wrap It Up Foaled Kenmare (FR) April 22nd, 2012 Highest Honor (FR) Se La Vie (FR) High River (FR) (2003) Fabulous Dancer (USA) Lady Winner (FR) Ameridienne (FR) E.B.F. Nominated. B.C. Nominated. 1st Dam SE LA VIE (FR), won 2 races at 2 and 3 years in France and £23,193 and placed 7 times; dam of one winner from 2 runners and 4 foals of racing age viz- French Emperor (IRE) (2009 c. by Holy Roman Emperor (IRE)), won 2 races at 2 years and £31,060 and placed twice viz third in Dubai Duty Free Railway Stakes, Curragh, Gr.2 and Alfred Nobel Rochestown Stakes, Naas, L. Cassells Rock (IRE) (2010 c. by Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)), placed 5 times at 2 and 3 years, 2013 in France and £12,033. Argayash Lake (IRE) (2011 c. by Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)), unraced to date. 2nd Dam LADY WINNER (FR), Champion older mare in Europe in 1990, won 6 races in France and in U.S.A. and £310,740 including Prix d'Astarte, Deauville, Gr.2, Chrysanthemum Handicap, Laurel, Gr.3, Prix Tantieme, Saint-Cloud, L. and All Along Stakes, Laurel, L., placed second in Ciga Prix de l'Opera, Longchamp, Gr.2 and Prix du Muguet, Saint-Cloud, Gr.3; dam of five winners from 8 runners and 10 foals of racing age including- DAYLIGHT COME (USA) (f. -

Pierre Viret, Die Onbekende Hervormer

1 Pierre Viret, die onbekende Hervormer ’n Bekendstelling van ’n vergete reus van die Reformasie ‘n Paar artikels afgelaai van die internet en saamgevat deur AH Bogaards 2020 2 Inhoudsopgawe 1. Pierre Viret: The Unknown Reformer .................................................................................... 5 Early Ministry ............................................................................................................................. 5 Reformation in Geneva ............................................................................................................... 6 Lausanne Disputation.................................................................................................................. 7 Founding of the Lausanne Academy .......................................................................................... 7 Viret and Calvin .......................................................................................................................... 7 A Friend Indeed .......................................................................................................................... 8 The Shadow of Death.................................................................................................................. 9 Battles with the Magistrates ...................................................................................................... 10 Ministry in France ..................................................................................................................... 11 A Lasting -

Southwest France Canal Tour | Small Group Tour | Odyssey Traveller

Australia 1300 888 225 New Zealand 0800 440 055 [email protected] From $14,995 AUD Single Room $17,095 AUD Twin Room $14,995 AUD Prices valid until 30th December 2021 18 days Duration France Destination Level 1 - Introductory to Moderate Activity Southwest France: Along the Canal du Midi Oct 18 2021 to Nov 04 2021 A journey through Southwest France along the Canal du Midi Join Odyssey Traveller as we explore the UNESCO-listed Canal du Midi in Southwest France with this tour. The Canal was engineered by Pierre-Paul Riquet as a means to increase trade from Bordeaux and the Atlantic to Sète and the Mediterranean. Taking approximately 14 years to complete, it is a feat of engineering ingenuity and artistic design, earning its title as one of the oldest operating canals in Europe and a treasure of world heritage scenery that shaped the Industrial Southwest France: Along the Canal du Midi 28-Sep-2021 1/15 https://www.odysseytraveller.com.au Australia 1300 888 225 New Zealand 0800 440 055 [email protected] Revolution and modern technology. This 17-day tour is orientated to the senior couple or solo traveller with a keen interest for engineering, architecture, and culture. The group will be escorted by a helpful Odyssey Traveller program leader and a number of knowledgeable local guides. We will delve into southern France’s rich history and wind along the Canal that links many of the area’s biggest cities and best attractions. On this tour, we will spend multiple nights in: Bordeaux, UNESCO-listed ‘Port of the Moon’, our Atlantic opening to the Canal. -

Contributions of the Ottoman Empire to the Construction of Modern Europe

CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TO THE CONSTRUCTION OF MODERN EUROPE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY MUSTAFA SERDAR PALABIYIK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS JUNE 2005 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science/Arts / Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Atilla Eralp Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science/Arts/Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. A. Nuri Yurdusev Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı (METU, IR) Assoc. Prof. Dr. A. Nuri Yurdusev (METU, IR) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ömer Turan (METU, HIST) ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: Mustafa Serdar PALABIYIK Signature: iii ABSTRACT CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TO THE CONSTRUCTION OF MODERN EUROPE Palabıyık, Mustafa Serdar M.Sc., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. A. Nuri Yurdusev June 2003, 159 pages This thesis aims to analyze the contributions of the Ottoman Empire to the construction of modern Europe in the early modern period. -

Calvin and the Reformation

Turning Points: God’s Faithfulness in Christian History 4. Reformation of Church and Doctrine: Luther and Calvin Sixteenth-Century Reformation Sixteenth-Century Reformation BACKGROUND Renaissance (1300-1500) created deep divisions in Europe: A. new states: France & England; then Spain, Portugal, Sweden, Scotland & smaller: Naples, Venice, Tuscany, Papal states. 100 Years War b/w France & England. B. Christendom divided: Great Schism w/2 popes Avignon & Rome 1378-1417. C. Holy Roman Empire (HRE): German-speaking confederation 300+ small states w/7 larger states alliance; & very powerful families. CONFEDERATION (like European Union) “Holy” & “Roman” = recreate Christian Roman Empire prior to destruction (410 AD by barbarians) Government of Holy Roman Empire context of martin luther Golden Bull of 1356 est. 7 “Electors” elected “Emperor” from among 7. [962-1806] Reichstag = (Imperial Diet) assembly of estates (parliament). 3 ecclesiastical Electors: (Roman Catholic Church temporal govts.!) *Archbishop of Mainz *Archbishop of Trier *Archbishop of Cologne 4 secular Electors: *King of Bohemia *Margrave of Brandenburg *Count Palatine of the Rhine become Reformed *Duke of Saxony become Lutheran 4 Sixteenth-Century Reformation Choices Correlations institutional forms Christianity & social-economic structure: Catholic, Lutheran, Church of England = appeal monarchical- hierarchy model. church governing followed social-economic= “Episcopal ” [top-down pope, cardinals, archbishops, etc.] Reformed/ Calvinism =appeal merchant elite: Free cities, independent regions (republics) freedom from larger forces w/ oligarchic model. church governing followed social-economic structure= “Presbyterian ” [shared leadership Synods] Independent /dissident groups = appeal peasants, urban workers (Anabaptist) church governing followed democratic model “Congregational ” [independent] Religious Divisions in 16th Century Europe Duchy of Saxony ( Northern Germany, Luther’s home ) w/Elbe River= trade, transportation. -

INSTITUTES of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY THEOLOGY INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles Used by permission from The Westminster Press All Rights Reserved B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 2 JOHN CALVIN: INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION EDITED BY JOHN T. MCNEILL Auburn Professor Emeritus of Church History Union Theological Seminary New York TRANSLATED AND INDEXED BY FORD LEWIS BATTLES Philip Schaff Professor of Church History The Hartford Theological Seminary Hartford, Connecticut in collaboration with the editor and a committee of advisers Philadelphia 3 GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE The Christian Church possesses in its literature an abundant and incomparable treasure. But it is an inheritance that must be reclaimed by each generation. THE LIBRARY OF CHRISTIAN CLASSICS is designed to present in the English language, and in twenty-six volumes of convenient size, a selection of the most indispensable Christian treatises written prior to the end of the sixteenth century. The practice of giving circulation to writings selected for superior worth or special interest was adopted at the beginning of Christian history. The canonical Scriptures were themselves a selection from a much wider literature. In the patristic era there began to appear a class of works of compilation (often designed for ready reference in controversy) of the opinions of well-reputed predecessors, and in the Middle Ages many such works were produced. These medieval anthologies actually preserve some noteworthy materials from works otherwise lost. In modern times, with the increasing inability even of those trained in universities and theological colleges to read Latin and Greek texts with ease and familiarity, the translation of selected portions of earlier Christian literature into modern languages has become more necessary than ever; while the wide range of distinguished books written in vernaculars such as English makes selection there also needful.