Slutversion Intro 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 Aboriginal survivors reach settlement with Church, Commonwealth cathnew.com Survivors of Aboriginal forced removal policies have signed a deal for compensation and apology 40 years after suffering sexual and physical abuse at the Garden Point Catholic Church mission on Melville Island, north of Darwin. Source: ABC News. “I’m happy, and I’m sad for the people who have gone already … we had a minute’s silence for them … but it’s been very tiring fighting for this for three years,” said Maxine Kunde, the leader Mgr Charles Gauci - Bishop of Darwin of a group of 42 survivors that took civil action against the church and Commonwealth in the Northern Territory Supreme Court. At age six, Ms Kunde, along with her brothers and sisters, was forcibly taken from her mother under the then-federal government’s policy of removing children of mixed descent from their parents. Garden Point survivors, many of whom travelled to Darwin from all over Australia, agreed yesterday to settle the case, and Maxine Kunde (ABC News/Tiffany Parker) received an informal apology from representatives of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, in a private session.Ms Kunde said members of the group were looking forward to getting a formal public apology which they had been told would be delivered in a few weeks’ time. Darwin Bishop Charles Gauci said on behalf of the diocese he apologised to those who were abused at Garden Point. -

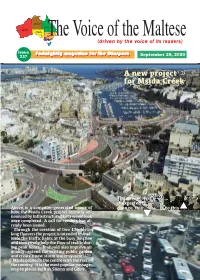

Layout VGD Copy

The Voic(edr iivoenf b yt thhe evo iicMe of aiitsl retaedesrse ) Issue FFoorrttnniigghhttllyy mmaaggaazziinnee ffoorr tthhee DDiiaassppoorraa September 2 237 9, 2020 AA nneeww pprroojjeecctt ffoorr MMssiiddaa CCrreeeekk The new project q is expected to Above is a computer-generated image of change this ....to this how the Msida Creek project recently an - nounced by Infrastructure Malta would look q once completed. A call for tenders has al - ready been issued. Through the creation of two 175-metre long flyovers the project is intended to erad - icate the traffic lights at the busy junction and immensely help the flow of traffic dur - ing peak hours. It should also improve air quality, extend the existing public garden and create a new storm water system. Msida connects the centre with the rest of the country. It is the most popular passage - way to places such as Sliema and G żira. 2 The Voice of the Maltese Tuesday September 29, 2020 Kummentarju: Il-qawwa tal-istampa miktuba awn iż-żmenijiet tal-pandemija COVID-19 ġabu għal kopji ta’ The Voice. Sa anke kellna talbiet biex magħhom ħafna ċaqlieq u tibdil fil-ħajja, speċjal - imwasslulhom kopja d-dar għax ma jistgħux joħorġu. ment fost dawk vulnerabbl, li fost kollox sabu Kellna wkoll djar tal-anzjani li talbuna kopji. F’każ Dferm aktar ħin liberu. Imma aktar minhekk qed isibu minnhom wassalnielhom kull edizzjoni, u tant ħadu wkoll nuqqas ta’ liberta’. pjacir jaqraw The Voice li sa kien hemm min, fost l-anz - Minħabba r-restrizzjonijiet u għal aktar sigurtá biex jani li ċemplilna biex juri l-apprezzament tiegħu. -

Annual Report 2017 Arts Council Malta Annual Report 2017 Contents

ARTS COUNCIL MALTA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ARTS COUNCIL MALTA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS Chair’s Foreword ����������������������������������� 4 Cultural Participation Survey 2016 ��48 Organisational Structure Artivisti �������������������������������������������������52 & Governance ����������������������������������7 EU Projects Office ������������������������������56 The Arts Council Malta Board & Directors �������������������������������������������� 8 The Cultural Programme of the 2017 Maltese Presidency of the The Strategy Team ������������������������������� 9 Council of the European Union ��������58 Arts Council Malta in 2017 ���������������� 10 Funding & Brokerage ��������������� 62 Government Budget 2017 Key figures for Funding allocations to ACM and Public Programmes in 2017���������������������������64 Cultural Organisations (PCOs) ���������12 Amounts Awarded in 2017 ����������������66 Strategy ������������������������������������������� 14 Funding Programmes – Evaluations 74 Progress to date for the Strategy2020 Actions ������������������������� 17 ACM Brokerage and Training Services 2017����������������������������������������75 ARTS COUNCIL MALTA Strategic Action Highlights ��44 ANNUAL REPORT ACMlab sessions 2017 ����������������������� 76 2017 The Malta Pavilion at the Biennale Arte 2017 �����������������������������46 ACM’S Digital Presence in 2017 ��������77 0051 – Cover.indd 3 03/05/2018 10:15 Cover shows an image from Human_Construct, Kane Cali, Project Support Grant – Malta Arts Fund� Photo by Alexandra Pace Report compiled -

2019 SPA Conf Abstracts .Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Perks, Richard (2018) Strung Together: A Practical Exploration of Music-Cultural Hybridity, Interaction, and Collaboration. In: Hybrid Practices: Methodologies, Histories, and Performance – A conference at the University of Malta, hosted by the School of Performing Arts, 13-15 March 2019, Malta. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/80754/ Document Version Supplemental Material Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Hybrid Practices: Methodologies, Histories, and Performance A conference at the University of Malta, hosted by the School of Performing Arts 13–15 March 2019 Abstracts Wednesday 13 March 8:30-9:00 Registration 9:00-9:10 Opening and Welcome 9:10-10:30 Keynote Speech Prof. Anne Bogart, SITI Company and Columbia University, US The Vital and Energetic Role of an Audience In our current digitally dominated environment, the theatre has become a sacred place wherein dramatic and democratic encounters can occur within the delineated time and space of a production. -

Annual Report 2019

i Annual Report 2019 Annual Report 2019 Annual Report 2019 Contents 2 3 Annual Report The Chairman’s Message 5 First published in 2020 by the National Book Council of Malta The National Writers’ Congress 8 2019 Central Public Library, Prof. J. Mangion Str., Floriana FRN 1800 The National Book Prize 10 ktieb.org.mt The Malta Book Festival 14 Printing: Gutenberg Press Foreign Work & Literary Exports 18 Design: Steven Scicluna Copyright text © Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ktieb The Campus Book Festival 22 Copyright photos © Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ktieb The Malta Book Fund 24 ISBN: 978-99957-939-1-3: Annual Report 2019 (Digital format) Audiovisual Productions 26 Other Contests 28 All rights reserved by the National Book Council This book is being disseminated free of charge and cannot be sold. It may be Other Initiatives 30 borrowed, donated and reproduced in part. It may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the Financial Report 32 National Book Council. ISBN & ISMN 36 Public Lending Rights Payments 68 About the National Book Council The Chairman’s message 4 The National Book Council is a public entity Staff and contact details 2019 was an eventful and challenging year in is progressing very well thanks to sustained 5 that caters for the Maltese book industry which the Council kept growing, receiving as public funding support. Admittedly, I had Annual Report with several important services for authors Executive Chairman much as an 80 per cent increase in its public strong qualms about some decisions made by and publishers whilst striving to encourage Mark Camilleri reading and promote the book as a medium of funding for its recurrent expenditure over newly-appointed bureaucrats in the finance Deputy Chairman communication in all its formats. -

Oaches Have Left Little Room for Reviewing the Poem As a Reading Experience

The Cantilena as a Reading Experience Bernard Micallef A patrimony of readings Emerging as a legible text from the comparative obscurity of its fifteenth- century world, Peter Caxaro’s Cantilena has understandably inspired primary interest in its medieval origins. The cultural and social climate of its historical era, the medieval medium in which it is written, and its author’s personal circumstances mark out an irresistible field for scholarly research. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the greater part of Cantilena studies have dwelt on Caxaro’s genealogy and public roles, on potential real-life motives behind his intricately wrought allegories of hopeless despair and regained fortitude, and on the vernacular idiom showcased in his poem. These predominantly biographical and philological approaches have left little room for reviewing the poem as a reading experience. Consequently, the performative aspect of the work has often been assigned a secondary status to the scholarly endeavour to put together an historical picture of the author’s life and times. To be sure, articles such as Oliver Friggieri’s “Il-Kantilena ta’ Pietru Caxaru: Stħarriġ Kritiku [Peter Caxaro’s Cantilena: A Critical Analysis]” have redressed the balance somewhat, providing a close and insightful analysis of the poem’s rhetorical and figurative dynamics. Nonetheless, most of us still associate the Cantilena primarily with the question whether its dominant allegory of a collapsed house were not representative of Caxaro’s public humiliation due to his thwarted -

Lonely Planet Publications 150 Linden St, Oakland, California 94607 USA Telephone: 510-893-8556; Facsimile: 510-893-8563; Web

Lonely Planet Publications 150 Linden St, Oakland, California 94607 USA Telephone: 510-893-8556; Facsimile: 510-893-8563; Web: www.lonelyplanet.com ‘READ’ list from THE TRAVEL BOOK by country: Afghanistan Robert Byron’s The Road to Oxiana or Eric Newby’s A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush, both all-time travel classics; Idris Shah’s Afghan Caravan – a compendium of spellbinding Afghan tales, full of heroism, adventure and wisdom Albania Broken April by Albania’s best-known contemporary writer, Ismail Kadare, which deals with the blood vendettas of the northern highlands before the 1939 Italian invasion. Biografi by Lloyd Jones is a fanciful story set in the immediate post-communist era, involving the search for Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha’s alleged double Algeria Between Sea and Sahara: An Algerian Journal by Eugene Fromentin, Blake Robinson and Valeria Crlando, a mix of travel writing and history; or Nedjma by the Algerian writer Kateb Yacine, an autobiographical account of childhood, love and Algerian history Andorra Andorra by Peter Cameron, a darkly comic novel set in a fictitious Andorran mountain town. Approach to the History of Andorra by Lídia Armengol Vila is a solid work published by the Institut d’Estudis Andorrans. Angola Angola Beloved by T Ernest Wilson, the story of a pioneering Christian missionary’s struggle to bring the gospel to an Angola steeped in witchcraft Anguilla Green Cane and Juicy Flotsam: Short Stories by Caribbean Women, or check out the island’s history in Donald E Westlake’s Under an English Heaven Antarctica Ernest Shackleton’s Aurora Australis, the only book ever published in Antarctica, and a personal account of Shackleton’s 1907-09 Nimrod expedition; Nikki Gemmell’s Shiver, the story of a young journalist who finds love and tragedy on an Antarctic journey Antigua & Barbuda Jamaica Kincaid’s novel Annie John, which recounts growing up in Antigua. -

Melita Historica Melita Melita Historica

MELITA HISTORICA MELITA HISTORICA Editor: David Mallia VOL. XVI No. 3 (2014) MALTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY MELITA HISTORICA VOL. XVI No. 3 (2014) MALTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Architecture in Post-Independence Malta Past, Present and Future Conrad Thake1 In July 1969, five years after Malta’s Independence, the prestigious British architecture journal, The Architecture Review issued a special issue entitled MALTA – Past, Present and Future. The foreword by the journal’s editors commenced as follows: ‘Since Malta achieved independence many changes have come to the island and even greater changes are likely, largely owing to the growth of tourism. Since the run-down of the British naval base and dockyards, it has been increasingly evident in spite of some successes in the light industries, that the future economy of the island must largely depend on tourism and on the climatic and other attractions it offers to retired people and such like. This means a vast amount of building – of villas, hotels and pleasure facilities of all kinds – and the main problem facing Malta at the moment, a problem much of the building that has already taken place alarmingly illustrates, is how to prevent all these developments in aid of tourism from destroying the very attractions the tourist come to enjoy.'2 True, the aftermath of Malta’s Independence witnessed an unprecedented ‘building boom’ as the island embarked on an intensive 1 Prof. Conrad Thake is an associate professor at the History of Art department, University of Malta. He trained as an architect and civil engineer in Malta, received an MA degree in Urban Planning from the Waterloo University, Canada, and a PhD degree in Architecture History from the University of California, Berkeley, (1996). -

A Refugee Appointed Next Governor of South Australia

MALTESE NEWSLETTER 54 AUGUST 2014 CONSULATE OF MALTA IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER FRANK L SCICLUNA - LINKING MALTA AND AUSTRALIA EMAIL: [email protected] Website: www.ozmalta.page4.me or ozmalta.com A Refugee Appointed Next Governor Of South Australia On Thursday, 26 June 2014, South Australia Premier the Hon Jay Weatherill MP announced that Her Majesty the Queen has approved the appointment of Mr. Hieu Van Le AO as the next Governor of South Australia. Mr. Weatherill said Mr. Le’s appointment heralds an historic moment for South Australia. “lt is a great honour to announce that Mr. Hieu Van Le will be South Australia’s 35th Governor — the first Asian migrant to rise to the position of Governor in our State’s history,” Mr. Weatherill said. Hieu Van Le Mr. Le said that his appointment sends The newly-appointed governor of SA with Mr Frank Scicluna during the launch the new Governor of SA a powerful message affirming South of the book - Maltese-SA Directory 2009 Australia’s inclusive and egalitarian society. At the same time, it represents a powerful symbolic acknowledgement of the contributions that all migrants have made and are continuing to make to our state. Mr. Le strongly believes that this appointment sends a positive message to people in many countries around the world, and in particular, our neighbouring countries in the Asia-Pacific region, of the inclusive and vibrant multicultural society of South Australia. In preparation for assuming his new office, Mr. Hieu Van Le AO has resigned as Chairman of the South Australian Multicultural and Ethnic Affairs Commission. -

Malta to Host C.H.O.G.M. in 2015

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 39 CONSULATE OF MALTA IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER MARCH 2014 FRANK L SCICLUNA - LINKING MALTA AND AUSTRALIA EMAIL: [email protected] Website: www.ozmalta.page4.me Convention for Maltese Living Abroad 2015: logo and memento design competition launched Malta’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs is planning to organise the 4th Convention for the Maltese Living Abroad in Malta during early April 2015. It is the intention of the Organising Committee of this Convention to involve to the fullest not only the Council for the Maltese Living Abroad (CMLA) who represent all Maltese Abroad, but the thousands of Maltese living around the world themselves. With this purpose in mind, the Organising Committee within the Ministry for Foreign Affairs is launching an international Logo and Memento Competition open for all Maltese nationals living abroad. Both logo and memento can be the same or different design(s) and should epitomise the spirit of Malta’s Diaspora and the Greater Malta concept. Artists may opt to make submissions for either the logo or memento or both. All participating works should be forwarded to the nearest Malta High Commission, Malta Embassy or Malta Permanent Representation. The final work will be chosen by an independent team of judges in Malta. Works must be submitted at the nearest Malta High Commission, Malta Embassy or Malta Permanent Representation by Friday, 30 May 2014 at noon. Works received after this date and time would not be considered. The contact details for the Malta High Commission in Canberra, Australia are: Postal address: 38 Culgoa Circuit, O’Malley, ACT, 2606 Email: [email protected] MALTA TO HOST C.H.O.G.M. -

Maltese Titles a Selection of Recent Publications

Maltese Titles A selection of recent publications casalinilibri PRESENTATION & SELECTION CRITERIA We are pleased to enclose our latest booklet on Maltese publications. The titles have been selected by our bibliographers for their particular relevance and importance. For the table of contents please consult our website at www.casalini.it We would be very pleased to handle your orders for these titles or any other European publications you may require. Please send any requests to [email protected]. Via Benedetto da Maiano 3 - 50014 Fiesole (Florence) - Italy Tel. +39 055 50181 - Fax +39 055 5018201 [email protected] - www.casalini.it Maltese Titles A selection of recent publications PHILOSOPHY & PSYCHOLOGY 1 Card no. 16804732 ATTARD, PIERRE. Is-Sintezii : Riinvenzjoni tar-Realtà / Pierre Attard. - [San Gwann]: BDL Publishing, 2016 96 pages : illustrations ; 21 cm. 9789995746865 195 B € 10,00 Includes bibliographical references. RELIGION 2 Card no. 16807605 VELLA, EDGAR, 1961-. Treasures of faith : relics and reliquaries in the Diocese of Malta during the Baroque period 1600-1798 / Edgar Vella. - Valletta, Malta: Midsea Books, 2016 228 pages : illustrations (chiefly color) ; 31 cm. 9789993275626 246 NK € 80,00 Bound. 3 Card no. 15827979 PISANI, PAUL GEORGE The battle of Lepanto : 7 October 1571, an unpublished hospitaller account / Paul George Pisani ; phography and design Daniel Cilia. - [Silema]: The Salesians of Don Bosco, 2015 248 pages : illustrations (some color) ; 32 cm. 9789995784638 271 DR € 55,00 Incl. trascription of orig. 16th cent. Italian ms. by L. Cenni (1623-1685), Italian Abbot, publ. for the first time. Bound. casalinibooklets 3 Social Sciences Maltese Titles 7 Card no. -

The English Poems of Victor Fenech

IN SEARCH OF A PERSONAL AND NATIONAL IDENTITY : THE ENGLISH POEMS OF VICTOR FENECH ARNOLD CASSOLA Abstract- This article examines the English poems that the Maltese con temporary writer Victor Fenech (1935-) published during the 1970s. Fenech considers the Maltese language to be quite limited since it keeps the Maltese people "locked out of the mainstream of international lit erature". English thus becomes the international medium that has the power to liberate the author from the restrictions imposed upon him by the national Maltese language. This article highlights the fact that F enech feels a deep sense of sorrow at the way human beings act. The writer therefore decides to distance himself in solitude from a valueless soci ety. Solitude, however, does not necessarily coincide with contemplative life. So much so, that the poet even indulges in 'political'poetry. The key elements that surface in F enech :S poetry seem to be : lack of faith in human beings; lack of faith in politics; even of faith in God. However, the author does find some consolation in his ideal female figure and in the way of life in little centres : happiness, if this is ever found, lies far away from the hustle and bustle of the big metropolis. The author of this article reaches the conclusion that F enech :S poetry should not be seen exclusively as a transcription of the poet:S feelings: it is also, and more especially so, the faithful chronicle of the epic story of a people who are always "licking wounds sustained for others" and who continuously search for a proper fixed identity.