Melita Theologica 57(1) 2006.PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Layout VGD Copy

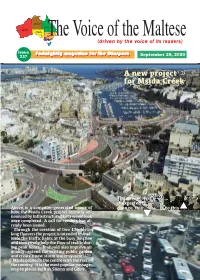

The Voic(edr iivoenf b yt thhe evo iicMe of aiitsl retaedesrse ) Issue FFoorrttnniigghhttllyy mmaaggaazziinnee ffoorr tthhee DDiiaassppoorraa September 2 237 9, 2020 AA nneeww pprroojjeecctt ffoorr MMssiiddaa CCrreeeekk The new project q is expected to Above is a computer-generated image of change this ....to this how the Msida Creek project recently an - nounced by Infrastructure Malta would look q once completed. A call for tenders has al - ready been issued. Through the creation of two 175-metre long flyovers the project is intended to erad - icate the traffic lights at the busy junction and immensely help the flow of traffic dur - ing peak hours. It should also improve air quality, extend the existing public garden and create a new storm water system. Msida connects the centre with the rest of the country. It is the most popular passage - way to places such as Sliema and G żira. 2 The Voice of the Maltese Tuesday September 29, 2020 Kummentarju: Il-qawwa tal-istampa miktuba awn iż-żmenijiet tal-pandemija COVID-19 ġabu għal kopji ta’ The Voice. Sa anke kellna talbiet biex magħhom ħafna ċaqlieq u tibdil fil-ħajja, speċjal - imwasslulhom kopja d-dar għax ma jistgħux joħorġu. ment fost dawk vulnerabbl, li fost kollox sabu Kellna wkoll djar tal-anzjani li talbuna kopji. F’każ Dferm aktar ħin liberu. Imma aktar minhekk qed isibu minnhom wassalnielhom kull edizzjoni, u tant ħadu wkoll nuqqas ta’ liberta’. pjacir jaqraw The Voice li sa kien hemm min, fost l-anz - Minħabba r-restrizzjonijiet u għal aktar sigurtá biex jani li ċemplilna biex juri l-apprezzament tiegħu. -

Oaches Have Left Little Room for Reviewing the Poem As a Reading Experience

The Cantilena as a Reading Experience Bernard Micallef A patrimony of readings Emerging as a legible text from the comparative obscurity of its fifteenth- century world, Peter Caxaro’s Cantilena has understandably inspired primary interest in its medieval origins. The cultural and social climate of its historical era, the medieval medium in which it is written, and its author’s personal circumstances mark out an irresistible field for scholarly research. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the greater part of Cantilena studies have dwelt on Caxaro’s genealogy and public roles, on potential real-life motives behind his intricately wrought allegories of hopeless despair and regained fortitude, and on the vernacular idiom showcased in his poem. These predominantly biographical and philological approaches have left little room for reviewing the poem as a reading experience. Consequently, the performative aspect of the work has often been assigned a secondary status to the scholarly endeavour to put together an historical picture of the author’s life and times. To be sure, articles such as Oliver Friggieri’s “Il-Kantilena ta’ Pietru Caxaru: Stħarriġ Kritiku [Peter Caxaro’s Cantilena: A Critical Analysis]” have redressed the balance somewhat, providing a close and insightful analysis of the poem’s rhetorical and figurative dynamics. Nonetheless, most of us still associate the Cantilena primarily with the question whether its dominant allegory of a collapsed house were not representative of Caxaro’s public humiliation due to his thwarted -

Slutversion Intro 1

Växjö Universitet Institutionen för Humaniora Nivå G3 Engelska GI1323 Handledare: Lena Christensen 15 högskolepoäng Examinator: Maria Olaussen 2009-06-01 Battling at two fronts. Friendship, loyalty and fascism in Requiem for a Malta fascist by Francis Ebejer. Martin Winberg Abstract A discussion about the role of fascism and the influence it has on the relations between the protagonist Lorenz and the characters Paul, Elena and Kos in Requiem for a Malta fascist by the Maltese author Francis Ebejer, as well as a brief historical background as to why Malta ended up in their de facto tangibly decisive situation during the Second World War. The discussion also treats subjects like loyalty and priority and how these are affected in a time of national and international crisis. List of contents: 1. Introduction........................................................................... 1 2. Historical background........................................................... 2 3. Theoretical background......................................................... 4 4. Lorenz’s complicated relationships....................................... 6 4.1. His best friend Paul..................................................... 6 4.2. Countess Elena Matevich............................................12 4.3. Cousin Kos and the home village................................16 5. Conclusion ............................................................................18 6. Bibliography......................................................................... 20 1. Introduction -

A Refugee Appointed Next Governor of South Australia

MALTESE NEWSLETTER 54 AUGUST 2014 CONSULATE OF MALTA IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER FRANK L SCICLUNA - LINKING MALTA AND AUSTRALIA EMAIL: [email protected] Website: www.ozmalta.page4.me or ozmalta.com A Refugee Appointed Next Governor Of South Australia On Thursday, 26 June 2014, South Australia Premier the Hon Jay Weatherill MP announced that Her Majesty the Queen has approved the appointment of Mr. Hieu Van Le AO as the next Governor of South Australia. Mr. Weatherill said Mr. Le’s appointment heralds an historic moment for South Australia. “lt is a great honour to announce that Mr. Hieu Van Le will be South Australia’s 35th Governor — the first Asian migrant to rise to the position of Governor in our State’s history,” Mr. Weatherill said. Hieu Van Le Mr. Le said that his appointment sends The newly-appointed governor of SA with Mr Frank Scicluna during the launch the new Governor of SA a powerful message affirming South of the book - Maltese-SA Directory 2009 Australia’s inclusive and egalitarian society. At the same time, it represents a powerful symbolic acknowledgement of the contributions that all migrants have made and are continuing to make to our state. Mr. Le strongly believes that this appointment sends a positive message to people in many countries around the world, and in particular, our neighbouring countries in the Asia-Pacific region, of the inclusive and vibrant multicultural society of South Australia. In preparation for assuming his new office, Mr. Hieu Van Le AO has resigned as Chairman of the South Australian Multicultural and Ethnic Affairs Commission. -

Malta to Host C.H.O.G.M. in 2015

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 39 CONSULATE OF MALTA IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER MARCH 2014 FRANK L SCICLUNA - LINKING MALTA AND AUSTRALIA EMAIL: [email protected] Website: www.ozmalta.page4.me Convention for Maltese Living Abroad 2015: logo and memento design competition launched Malta’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs is planning to organise the 4th Convention for the Maltese Living Abroad in Malta during early April 2015. It is the intention of the Organising Committee of this Convention to involve to the fullest not only the Council for the Maltese Living Abroad (CMLA) who represent all Maltese Abroad, but the thousands of Maltese living around the world themselves. With this purpose in mind, the Organising Committee within the Ministry for Foreign Affairs is launching an international Logo and Memento Competition open for all Maltese nationals living abroad. Both logo and memento can be the same or different design(s) and should epitomise the spirit of Malta’s Diaspora and the Greater Malta concept. Artists may opt to make submissions for either the logo or memento or both. All participating works should be forwarded to the nearest Malta High Commission, Malta Embassy or Malta Permanent Representation. The final work will be chosen by an independent team of judges in Malta. Works must be submitted at the nearest Malta High Commission, Malta Embassy or Malta Permanent Representation by Friday, 30 May 2014 at noon. Works received after this date and time would not be considered. The contact details for the Malta High Commission in Canberra, Australia are: Postal address: 38 Culgoa Circuit, O’Malley, ACT, 2606 Email: [email protected] MALTA TO HOST C.H.O.G.M. -

Maltese Titles a Selection of Recent Publications

Maltese Titles A selection of recent publications casalinilibri PRESENTATION & SELECTION CRITERIA We are pleased to enclose our latest booklet on Maltese publications. The titles have been selected by our bibliographers for their particular relevance and importance. For the table of contents please consult our website at www.casalini.it We would be very pleased to handle your orders for these titles or any other European publications you may require. Please send any requests to [email protected]. Via Benedetto da Maiano 3 - 50014 Fiesole (Florence) - Italy Tel. +39 055 50181 - Fax +39 055 5018201 [email protected] - www.casalini.it Maltese Titles A selection of recent publications PHILOSOPHY & PSYCHOLOGY 1 Card no. 16804732 ATTARD, PIERRE. Is-Sintezii : Riinvenzjoni tar-Realtà / Pierre Attard. - [San Gwann]: BDL Publishing, 2016 96 pages : illustrations ; 21 cm. 9789995746865 195 B € 10,00 Includes bibliographical references. RELIGION 2 Card no. 16807605 VELLA, EDGAR, 1961-. Treasures of faith : relics and reliquaries in the Diocese of Malta during the Baroque period 1600-1798 / Edgar Vella. - Valletta, Malta: Midsea Books, 2016 228 pages : illustrations (chiefly color) ; 31 cm. 9789993275626 246 NK € 80,00 Bound. 3 Card no. 15827979 PISANI, PAUL GEORGE The battle of Lepanto : 7 October 1571, an unpublished hospitaller account / Paul George Pisani ; phography and design Daniel Cilia. - [Silema]: The Salesians of Don Bosco, 2015 248 pages : illustrations (some color) ; 32 cm. 9789995784638 271 DR € 55,00 Incl. trascription of orig. 16th cent. Italian ms. by L. Cenni (1623-1685), Italian Abbot, publ. for the first time. Bound. casalinibooklets 3 Social Sciences Maltese Titles 7 Card no. -

The English Poems of Victor Fenech

IN SEARCH OF A PERSONAL AND NATIONAL IDENTITY : THE ENGLISH POEMS OF VICTOR FENECH ARNOLD CASSOLA Abstract- This article examines the English poems that the Maltese con temporary writer Victor Fenech (1935-) published during the 1970s. Fenech considers the Maltese language to be quite limited since it keeps the Maltese people "locked out of the mainstream of international lit erature". English thus becomes the international medium that has the power to liberate the author from the restrictions imposed upon him by the national Maltese language. This article highlights the fact that F enech feels a deep sense of sorrow at the way human beings act. The writer therefore decides to distance himself in solitude from a valueless soci ety. Solitude, however, does not necessarily coincide with contemplative life. So much so, that the poet even indulges in 'political'poetry. The key elements that surface in F enech :S poetry seem to be : lack of faith in human beings; lack of faith in politics; even of faith in God. However, the author does find some consolation in his ideal female figure and in the way of life in little centres : happiness, if this is ever found, lies far away from the hustle and bustle of the big metropolis. The author of this article reaches the conclusion that F enech :S poetry should not be seen exclusively as a transcription of the poet:S feelings: it is also, and more especially so, the faithful chronicle of the epic story of a people who are always "licking wounds sustained for others" and who continuously search for a proper fixed identity. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Il-Kantilena by Pietru Caxaro Il-Kantilena Ta' Pietru Caxaro Interpretazzjoni Rinaxximentali

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Il-Kantilena by Pietru Caxaro Il-Kantilena Ta' Pietru Caxaro Interpretazzjoni Rinaxximentali. "Fuq il-konklużjonijiet ippubblikati fl-ewwel studju tiegħi dwar il-Kantilena (1992) bqajt matul is-snin nibni konklużjonijiet oħrajn li jissoktaw juru l- importanza storika ta' dawn l-għoxrin vers. Hemm l-importanza tagħha bħala xogħol letterarju bikri bil-Malti, imma wkoll, u wisq aktar, bħala dokument li jixħet dawl fuq dik li nixtieq insejħilha 'L-Istorja Tal-Maltin', f'kuntrast ma'dik li hi magħrufa bhala 'l-Istorja ta' Malta'. Fl-isfond tan- nisġa ta' elementi Għarbin u elementi Sqallin tinkiseb definizzjoni sħiħa tal-Malti bħala djalett li kiber u sar lingwa. Iżda wisq iżjed minn hekk, illum nikkonkludi li hemm ukoll il-muftieħ għall-għarfien etniku tal-istess poplu li jitħaddet ilsien li hu taħlita: Semitiku-Latin. Ir-rikkezza enormi tal-lingwa Maltija tiftiehem minnufih f'dan id-dawl: hi lingwa li stagħniet billi laggħet fiha stess żewġ kulturi kbar. Il-profondità tal-prezenza tal-wirt Sqalli turi li hemm livelli u kundizzjonijiet varji fir relazzjoni bejn iż-żewġ gżejjer." Oliver Friggieri. Il-Kantilena by Pietru Caxaro. Fr. Mark Montebello O.P. It- Torca tal-Hadd, 19 ta’ Lulju 2009. Pietru Caxaru u l-Kantilena tieghu. Il-familja Caxaru kienet wahda qadima f’Malta fis-sekli 15 u 16. Pietru Caxaru, membru ta’ din il-familja, kiteb dik li s’issa hija maghrufa li hija l- eqdem poezija bil-Malti, maghrufa bhala “Il-Kantilena” jew “Xidew il-Qada”. Bejn wiehed u l-iehor, din il-poezija nkitbet madwar l-1450. Pietru Caxaru, il-kittieb famuz taghha, miet fl-1485. -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,675 Prezz/Price €6.66 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette Il-Ġimgħa, 30 ta’ Lulju, 2021 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Friday, 30th July, 2021 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Notifikazzjonijiet tal-Gvern ............................................................................................. 7637 - 7660 Government Notices ......................................................................................................... 7637 - 7660 Avviżi tal-Pulizija ............................................................................................................ 7661 Police Notices .................................................................................................................. 7661 Avviżi lill-Baħħara ........................................................................................................... 7661 - 7665 Notices to Mariners .......................................................................................................... 7661 - 7665 Opportunitajiet ta’ Impjieg ............................................................................................... 7665 - 7738 Employment Opportunities .............................................................................................. 7665 - 7738 Avviżi tal-Gvern ............................................................................................................... 7738 - 7752 Notices ............................................................................................................................. -

Ernle Bradford's the Great Siege

www.libridergi.org Epigrafi, Çeviri ve Eleştiri Dergisi Journal of Epigraphy, Reviews and Translations Sayı VI (2020) Review: Ernle Bradford’s The Great Siege: Malta 1565, 1961, its New Subtitle of 2010-2019, Clash of Cultures: Christian Knights Defend Western Civilization Against the Moslem Tide, and the Deliberate Omission of 16th c. Burmola (Burmula- Bormola-Bormla-Cospicua) - A Best-Selling Falsification of History in the 21st century. T. M. P. Duggan Libri: Epigrafi, Çeviri ve Eleştiri Dergisi’nde bulunan içeriklerin tümü kullanıcılara açık, serbestçe/ücretsiz “açık erişimli” bir dergidir. Kullanıcılar, yayıncıdan ve yazar(lar)dan izin almaksızın, dergideki kitap tanıtımlarını, eleştirileri ve çevirileri tam metin olarak okuyabilir, indirebilir, dağıtabilir, çıktısını alabilir ve kaynak göstererek bağlantı verebilir. Libri, uluslararası hakemli elektronik (online) bir dergi olup değerlendirme süreci biten kitap tanıtımları, eleştiriler ve çeviriler derginin web sitesinde (libridergi.org) yıl boyunca ilgili sayının içinde (Sayı VI: Ocak-Aralık 2020) yayımlanır. Aralık ayı sonunda ilgili yıla ait sayı tamamlanır. Dergide yayımlanan eserlerin sorumluluğu yazarlarına aittir. Atıf Düzeni T. M. P. Duggan, “Review: Ernle Bradford’s The Great Siege: Malta 1565, 1961, its New Subtitle of 2010-2019, Clash of Cultures: Christian Knights Defend Western Civilization Against the Moslem Tide, and the Deliberate Omission of 16th c. Burmola (Burmula-Bormola-Bormla-Cospicua) - A Best-Selling Falsification of History in the 21st Century”. Writer: Ernle -

Universidade De São Paulo Faculdade De Filosofia

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS CLÁSSICAS E VERNÁCULAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LITERATURA PORTUGUESA LEONARDO ZUCCARO O discurso evidente: Um estudo da descrição na obra impressa de Manuel Botelho de Oliveira Versão corrigida São Paulo 2019 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS CLÁSSICAS E VERNÁCULAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LITERATURA PORTUGUESA O discurso evidente: Um estudo da descrição na obra impressa de Manuel Botelho de Oliveira Versão Corrigida Leonardo Zuccaro Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao programa de Pós-graduação em Literatura Portuguesa da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, da Universidade de São Paulo, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Literatura Portuguesa. Orientadora: Profª. Dra. Adma Fadul Muhana. São Paulo 2019 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo Zuccaro, Leonardo Z94d O discurso evidente: Um estudo da descrição na obra impressa de Manuel Botelho de Oliveira / Leonardo Zuccaro ; orientadora Adma Muhana. - São Paulo, 2019. 264 f. Dissertação (Mestrado)- Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Letras Clássicas e Vernáculas. Área de concentração: Literatura Portuguesa. 1. descrição. 2. letras seiscentistas. 3. poética. 4. retórica. 5. Manuel Botelho de Oliveira. I. Muhana, Adma, orient. II. Título. UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE F FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ENTREGA DO EXEMPLAR CORRIGIDO DA DISSERTAÇÃO/TESE Termo de Ciência e Concordância do (a) orientador (a) Nome do (a) aluno (a): Leonardo Zuccaro Data da defesa: 03/10/2019 Nome do Prof. -

Romano-Arabica XIV, 2014

UNIVERSITY OF BUCHAREST CENTER FOR ARAB STUDIES ROMANO-ARABICA XIV ‘Āmmiyya and Fuṣḥā in Linguistics and Literature editura universităţii din bucureşti ® – 2014 – Editors: George Grigore (University of Bucharest, e-mail: [email protected]) Laura Sitaru (University of Bucharest, e-mail: [email protected]) Assistant Editors: Gabriel Biţună (University of Bucharest, e-mail: [email protected]) Georgiana Nicoarea (University of Bucharest, e-mail: [email protected]) Ovidiu Pietrăreanu (University of Bucharest, e-mail: [email protected]) Editorial and Advisory Board: Ramzi Baalbaki (American University of Beirut, Lebanon) Ioana Feodorov (Institute for South-East European Studies, Bucharest, Romania) Sabry Hafez (Qatar University, Qatar / University of London, United Kingdom) Marcia Hermansen (Loyola University, Chicago, USA) Pierre Larcher (Aix-Marseille University, France) Jérôme Lentin (INALCO, Paris, France) Giuliano Mion (“Gabriele d’Annunzio” University, Chieti-Pescara, Italy) Luminiţa Munteanu (University of Bucharest, Romania) Stephan Procházka (University of Vienna, Austria) Valeriy Rybalkin (“Taras Shevchenko” National University of Kyiv, Ukraine) Shabo Talay (University of Bergen, Norway) Irina Vainovski-Mihai (“Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University, Bucharest, Romania) Ángeles Vicente (University of Zaragoza, Spain) John O. Voll (Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., USA) Cover: Wi’ām (Harmony), by G. Bițună Published by: © Center for Arab Studies Pitar Moş Street no 7-13, Sector 1, 010451, Bucharest, Romania http://araba.lls.unibuc.ro/ Phone : 0040-21-305.19.50 © Editura Universităţii din Bucureşti Şos. Panduri, 90-92, Bucureşti – 050663; Telefon/Fax: 0040-21-410.23.84 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Internet: www.editura.unibuc.ro ISSN 1582-6953 Contents ,(يشار آجات؛ تيسير محمد الزيادات) Yaşar Acat; Tayseer Mohammad al-Zyadat Moral Values in Mḥallami Proverbs)...........................................