Looking Back on 'The Cantilena of Peter Caxaro'*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Layout VGD Copy

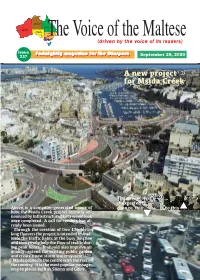

The Voic(edr iivoenf b yt thhe evo iicMe of aiitsl retaedesrse ) Issue FFoorrttnniigghhttllyy mmaaggaazziinnee ffoorr tthhee DDiiaassppoorraa September 2 237 9, 2020 AA nneeww pprroojjeecctt ffoorr MMssiiddaa CCrreeeekk The new project q is expected to Above is a computer-generated image of change this ....to this how the Msida Creek project recently an - nounced by Infrastructure Malta would look q once completed. A call for tenders has al - ready been issued. Through the creation of two 175-metre long flyovers the project is intended to erad - icate the traffic lights at the busy junction and immensely help the flow of traffic dur - ing peak hours. It should also improve air quality, extend the existing public garden and create a new storm water system. Msida connects the centre with the rest of the country. It is the most popular passage - way to places such as Sliema and G żira. 2 The Voice of the Maltese Tuesday September 29, 2020 Kummentarju: Il-qawwa tal-istampa miktuba awn iż-żmenijiet tal-pandemija COVID-19 ġabu għal kopji ta’ The Voice. Sa anke kellna talbiet biex magħhom ħafna ċaqlieq u tibdil fil-ħajja, speċjal - imwasslulhom kopja d-dar għax ma jistgħux joħorġu. ment fost dawk vulnerabbl, li fost kollox sabu Kellna wkoll djar tal-anzjani li talbuna kopji. F’każ Dferm aktar ħin liberu. Imma aktar minhekk qed isibu minnhom wassalnielhom kull edizzjoni, u tant ħadu wkoll nuqqas ta’ liberta’. pjacir jaqraw The Voice li sa kien hemm min, fost l-anz - Minħabba r-restrizzjonijiet u għal aktar sigurtá biex jani li ċemplilna biex juri l-apprezzament tiegħu. -

Growing up in Hospitaller Malta (1530- 1798): Sources and Methodologies for the History of Childhood and Adolescence

Growing Up in Hospitaller Malta (1530- 1798): Sources and Methodologies for the History of Childhood and Adolescence Emanuel Buttigieg University of Malta ABSTRACT The study of young people in the past is fraught with methodological problems and unearthing source material on children and adolescents can be problematic. It requires the adoption of a different set of lenses through which textual primary material can be viewed. This entails striving to recognise and release previously unheard voices. Fur- thermore, the textual material can be complemented by an array of visual and mate- rial objects that have preserved a certain image of children and adolescents in the past. This chapter commences with a brief outline of the methodological developments that have taken place in this field since Philippe Ariès’s seminal book appeared in 1960, and traces the resulting changes and innovations that concern sources. In particular, it will underline the importance to historians of taking into account recent developments in the field of childhood archaeology. Furthermore, the fundamental role of religion in people’s lives in early modern times necessarily influenced their upbringing. In turn, most of the sources that are available from this era – court records, statutes, paintings – were either produced by religious institutions, or were heavily influenced by religious beliefs. Thus, this chapter will strive to demonstrate how approaches used in one place can be adapted and used in different historiographical contexts, and how vital it is to adopt an interdisciplinary approach. L-istudju dwar it-tfulija u l-adoloxenza fil-passat ipoġġi lill-istoriku biswit sfidi kbar fejn jidħol il-materjal li jista’ jitfa’ dawl fuq dawn, kif ukoll liema metodoloġija wieħed għandu juża sabiex jgħarbel u jifhem l-idea u l-esperjenza li tkun tifel / tifla u adoloxenti fl-imgħoddi. -

The DEVELOPMENT of the Maltese Insurance Industry This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Development of the Maltese Insurance Industry: a Comprehensive Study

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MAltESE INSURANCE INDUSTRY This page intentionally left blank THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MALTESE INSURANCE INDUSTRY: A COMPREHENSIVE StUDY MARK LAURENCE ZAMMIT, JONATHAN SPITERI AND SIMON GRIMA Faculty of Economics, Management and Accountancy, Insurance Department, University of Malta, Malta United Kingdom – North America – Japan – India – Malaysia – China Emerald Publishing Limited Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley BD16 1WA, UK First edition 2018 Copyright © 2018 Emerald Publishing Limited Reprints and permissions service Contact: [email protected] No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. Any opinions expressed in the chapters are those of the authors. Whilst Emerald makes every effort to ensure the quality and accuracy of its content, Emerald makes no representation implied or otherwise, as to the chapters’ suitability and application and disclaims any warranties, express or implied, to their use. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-78756-978-2 (Print) ISBN: 978-1-78756-977-5 (Online) ISBN: 978-1-78756-979-9 (Epub) Acknowledgements We would like to thank the people who participated in the interviews for their patience, their insight and knowledge which was greatly valued and useful for the compilation of this book. Our thanks go to Dr Joan Abela, Curator of the Notarial Archives, for her help and guidance in the archival research conducted and with the translations required to interpret the contracts held there. -

Oaches Have Left Little Room for Reviewing the Poem As a Reading Experience

The Cantilena as a Reading Experience Bernard Micallef A patrimony of readings Emerging as a legible text from the comparative obscurity of its fifteenth- century world, Peter Caxaro’s Cantilena has understandably inspired primary interest in its medieval origins. The cultural and social climate of its historical era, the medieval medium in which it is written, and its author’s personal circumstances mark out an irresistible field for scholarly research. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the greater part of Cantilena studies have dwelt on Caxaro’s genealogy and public roles, on potential real-life motives behind his intricately wrought allegories of hopeless despair and regained fortitude, and on the vernacular idiom showcased in his poem. These predominantly biographical and philological approaches have left little room for reviewing the poem as a reading experience. Consequently, the performative aspect of the work has often been assigned a secondary status to the scholarly endeavour to put together an historical picture of the author’s life and times. To be sure, articles such as Oliver Friggieri’s “Il-Kantilena ta’ Pietru Caxaru: Stħarriġ Kritiku [Peter Caxaro’s Cantilena: A Critical Analysis]” have redressed the balance somewhat, providing a close and insightful analysis of the poem’s rhetorical and figurative dynamics. Nonetheless, most of us still associate the Cantilena primarily with the question whether its dominant allegory of a collapsed house were not representative of Caxaro’s public humiliation due to his thwarted -

State of Archives Report (2012).Pdf

STATE OF ARCHIVES REPORT 2012 STATE OF ARCHIVES REPORT 2012 1 2 REPORT ON THE STATE OF MALTESE ARCHIVES Compiled by the National Archives on behalf of the National Archives Council February 2014 © 2014 THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES COUNCIL Published by The National Archives Council, February 2014 c/o National Archives Hospital Street Rabat RBT1043 Malta www.nationalarchives.gov.mt STATE OF ARCHIVES REPORT 2012 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Hon. Evarist Bartolo, Minister for Education and Employment, and his staff; Hon. Dolores Cristina, former Minister for Education, and her staff; President and members of the National Archives Council; National Archivist Charles J. Farrugia and the staff at the three repositories of the National Archives; the Friends of the National Archives; the Notarial Archives Resources Council; Palazzo Falson; National Library of Malta; Archdiocese Archives; University of Malta; Mr Martin Hampton. Photography: Archdiocese Archives; National Library of Malta; Notarial Archives; Palazzo Falson; University of Malta; Joseph Amodio; Stephen Busuttil; Paul Falzon; Marlene Gouder. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD BY THE HON MINISTER E. BARTOLO 5 MESSAGE BY COUNCIL PRESIDENT, DR W. ZAMMIT 6 MESSAGE BY THE NATIONAL ARCHIVIST MR C. J. FARRUGIA 7 NATIONAL ARCHIVES COUNCIL 9 THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES COUNCIL 10 FUNCTIONS 11 COUNCIL MEMBERS 11 SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES 12 NATIONAL ARCHIVES 21 RECORDS MANAGEMENT UNIT ARCHIVES PROCESSING UNIT 22 NEW CONSERVATION FACILITIES 24 PUBLIC SERVICES UNIT 26 OUTREACH 26 INTERNATIONAL FORA 28 OTHER ARCHIVES 33 THE NOTARIAL ARCHIVES 34 OLOF GOLLCHER ARCHIVES 35 THE NATIONAL LIBRARY 36 THE ARCHDIOCESE ARCHIVES 38 UNIVERSITY OF MALTA LIBRARY 40 HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE 2011 FORUM 43 REFERENCES 44 STATE OF ARCHIVES REPORT 2012 3 4 FOREWORD BY THE HON EVARIST BARTOLO MP MINISTER FOR EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT This is the third State of Archives Report since the requirement to publish such a document was included in the National Archives Act of 2005. -

Book Reviews 6'7 Book Reviews G

BOOK REVIEWS 6'7 BOOK REVIEWS G. WETTINGER - M. FSADNI O.P., Peter Caxaro's Cantilena, a poem in medieval Maltese, Malta, 1968, 52 p. The poem dedicated to Grand Master Nicholas Cotoner (166371680) by G.F. Bonamico (1639-1680) has constantly been pointed out by scholars of Maltese Literature as being the earliest evidence of written Maltese. The search for earlier examples of written Maltese had always proved fruit less. G. Wettinger and M. Fsadni, however, have succeeded in unearthing an earlier document in Maltese: Peter Caxaro's CantiLena, which they discovered in the Notarial Archives in Valletta in a register containing the deeds of Brandano de Caxario. It is to their credit that this unique example of written Maltese dating from the latter half of the fifteenth Century has come to light. This book presenting the discovery of these two gentlemen is a synthe sis of the conclusions arrived at, after long research work in the Notarial Archives and the Archives of the Royal Malta Library - a scholarly work in which assertions are supported by, documentary evidence. In Part One of this publication, after some brief notes concerning the actual discovery of the CantiLena, the authors give a survey of the studies made by other scholars in their search of early examples of written Maltese. The question of the authorship of the CantiLena is then treated at full length. The interesting biographical details about Brandano de Caxario and his ancestor Peter make the reader familiar with the prominent Caxaro family that flourished in Malta in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. -

Slutversion Intro 1

Växjö Universitet Institutionen för Humaniora Nivå G3 Engelska GI1323 Handledare: Lena Christensen 15 högskolepoäng Examinator: Maria Olaussen 2009-06-01 Battling at two fronts. Friendship, loyalty and fascism in Requiem for a Malta fascist by Francis Ebejer. Martin Winberg Abstract A discussion about the role of fascism and the influence it has on the relations between the protagonist Lorenz and the characters Paul, Elena and Kos in Requiem for a Malta fascist by the Maltese author Francis Ebejer, as well as a brief historical background as to why Malta ended up in their de facto tangibly decisive situation during the Second World War. The discussion also treats subjects like loyalty and priority and how these are affected in a time of national and international crisis. List of contents: 1. Introduction........................................................................... 1 2. Historical background........................................................... 2 3. Theoretical background......................................................... 4 4. Lorenz’s complicated relationships....................................... 6 4.1. His best friend Paul..................................................... 6 4.2. Countess Elena Matevich............................................12 4.3. Cousin Kos and the home village................................16 5. Conclusion ............................................................................18 6. Bibliography......................................................................... 20 1. Introduction -

A Refugee Appointed Next Governor of South Australia

MALTESE NEWSLETTER 54 AUGUST 2014 CONSULATE OF MALTA IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER FRANK L SCICLUNA - LINKING MALTA AND AUSTRALIA EMAIL: [email protected] Website: www.ozmalta.page4.me or ozmalta.com A Refugee Appointed Next Governor Of South Australia On Thursday, 26 June 2014, South Australia Premier the Hon Jay Weatherill MP announced that Her Majesty the Queen has approved the appointment of Mr. Hieu Van Le AO as the next Governor of South Australia. Mr. Weatherill said Mr. Le’s appointment heralds an historic moment for South Australia. “lt is a great honour to announce that Mr. Hieu Van Le will be South Australia’s 35th Governor — the first Asian migrant to rise to the position of Governor in our State’s history,” Mr. Weatherill said. Hieu Van Le Mr. Le said that his appointment sends The newly-appointed governor of SA with Mr Frank Scicluna during the launch the new Governor of SA a powerful message affirming South of the book - Maltese-SA Directory 2009 Australia’s inclusive and egalitarian society. At the same time, it represents a powerful symbolic acknowledgement of the contributions that all migrants have made and are continuing to make to our state. Mr. Le strongly believes that this appointment sends a positive message to people in many countries around the world, and in particular, our neighbouring countries in the Asia-Pacific region, of the inclusive and vibrant multicultural society of South Australia. In preparation for assuming his new office, Mr. Hieu Van Le AO has resigned as Chairman of the South Australian Multicultural and Ethnic Affairs Commission. -

Black African Slaves in Malta 65 Black African Slaves in Malta Godfrey Wettinger

PART TWO The Political Role Played by Fortified Islands in the Mediterranean: The Malta Example Part Two 63 15.03.18, 09:32 Part Two 64 15.03.18, 09:32 Black African Slaves in Malta 65 Black African Slaves in Malta Godfrey Wettinger The Problem: Black African Slaves in Malta My study of Slavery in Malta originally entitled Some Aspects of Slavery in Malta during the Rule of the Order was first conceived to deal principally with the slaves or prisoners that resulted from the never ending Crusade fought by the Order of St John with the Turks and Moors in the Mediterranean Sea and on its shores. One’s first impression was that it would deal almost entirely with white or off-white captives who were former inhabitants of the shores and towns of Tunisia, Tripolitania, Algeria and the Levant including the rest of the Ottoman Empire. Although people in Malta still speak of iswed Tork, “as black as a Turk”, the latter meaning a Muslim and without precise ethnic significance, and a number of old town houses have the statue of a black African slave at the head of the staircase, it still seemed as if the typical slave in Malta during early modern times was a Moor or Turk, of whom it is known Malta had a constant number that varied between 500 early in the sixteenth century, went up to about a couple of thousands in the seventeenth century and perhaps exceeded three thousands in the opening decades of the eighteenth century, to be gradually reduced during the course of that century until it was finally ended by the operations both of the Emperor of Morocco and finally of General Bonaparte and later Maltese authorities. -

Annual Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Capital Works 1.1 National Funds 3 1.2 National Monuments 8 1.3 EU Co-Funded Projects 9 2. Exhibitions and Events 14 3. Collections and Research 17 4. Conservation 4.1 Paintings, Polychrome Sculpture and Wood Sculpture 27 4.2 Stone, Ceramics, Metal and Glass 29 4.3 Textiles, Books and Paper 30 4.4 Diagnostic Sciences Laboratories 31 5. Education, Publications and Outreach 5.1 Thematic Events and Hands-on Sessions 32 5.2 Publications 37 6. Other Corporate 39 7. Visitor Statistics and Analysis 7.1 Admissions 42 7.2 Statistical Analysis 43 8. Appendix 1 – Calendar of Events 8.1 Exhibitions Hosted by HM 54 8.2 Exhibitions Organised by HM 54 8.3 Exhibitions in Collaboration with Others 55 8.4 Exhibitions in which HM Participated 56 8.5 Lectures Organised/Hosted by HM 57 8.6 Events Organised by HM 58 8.7 Events in HM Participated 64 8.8 Organised in Collaboration with Others 65 8.9 Events Hosted by HM 68 9. Appendix 2 – Purchase of Modern and Contemporary Artworks 71 10. Appendix 3 – Acquisition of Natural History Specimens 72 11. Appendix 4 – Acquisition of Cultural Heritage Objects 73 2 1. CAPITAL WORKS 1.1 NATIONAL FUNDS During the year under review design for improvements to the layout in the ticketing and shop area of the Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra visitor centre was concluded and manufacture of furniture started. Such works will include the construction of a site office, new ticketing facilities and new larger shop within the existing building in order to maximize shop space and visitor flow. -

Instrument Building and Musical Culture in Seventeenth-Century Malta

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Music Instrument Building and Musical Culture in Seventeenth-Century Malta: the luthier Mattheo Morales by Anna Borg Cardona Thesis for the degree of PhD Music Submitted November 2017 The research work disclosed in this thesis is partly funded by the Malta Government Scholarship Scheme UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Music Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy INSTRUMENT BUILDING AND MUSICAL CULTURE IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MALTA: THE LUTHIER MATTHEO MORALES Anna Borg Cardona By the seventeenth century, Malta had become a nucleus of cultural activity. It provides us with totally new perspectives on the production and consumption of music within a Mediterranean context. -

Malta to Host C.H.O.G.M. in 2015

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 39 CONSULATE OF MALTA IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER MARCH 2014 FRANK L SCICLUNA - LINKING MALTA AND AUSTRALIA EMAIL: [email protected] Website: www.ozmalta.page4.me Convention for Maltese Living Abroad 2015: logo and memento design competition launched Malta’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs is planning to organise the 4th Convention for the Maltese Living Abroad in Malta during early April 2015. It is the intention of the Organising Committee of this Convention to involve to the fullest not only the Council for the Maltese Living Abroad (CMLA) who represent all Maltese Abroad, but the thousands of Maltese living around the world themselves. With this purpose in mind, the Organising Committee within the Ministry for Foreign Affairs is launching an international Logo and Memento Competition open for all Maltese nationals living abroad. Both logo and memento can be the same or different design(s) and should epitomise the spirit of Malta’s Diaspora and the Greater Malta concept. Artists may opt to make submissions for either the logo or memento or both. All participating works should be forwarded to the nearest Malta High Commission, Malta Embassy or Malta Permanent Representation. The final work will be chosen by an independent team of judges in Malta. Works must be submitted at the nearest Malta High Commission, Malta Embassy or Malta Permanent Representation by Friday, 30 May 2014 at noon. Works received after this date and time would not be considered. The contact details for the Malta High Commission in Canberra, Australia are: Postal address: 38 Culgoa Circuit, O’Malley, ACT, 2606 Email: [email protected] MALTA TO HOST C.H.O.G.M.