Ernle Bradford's the Great Siege

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Celestial Wings / Edgar D

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitcomb. Edgar D. On Celestial Wings / Edgar D. Whitcomb. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. United States. Army Air Forces-History-World War, 1939-1945. 2. Flight navigators- United States-Biography. 3. World War, 1939-1945-Campaigns-Pacific Area. 4. World War, 1939-1945-Personal narratives, American. I. Title. D790.W415 1996 940.54’4973-dc20 95-43048 CIP ISBN 1-58566-003-5 First Printing November 1995 Second Printing June 1998 Third Printing December 1999 Fourth Printing May 2000 Fifth Printing August 2001 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication has been reviewed by security and policy review authorities and is cleared for public release. Digitize February 2003 from August 2001 Fifth Printing NOTE: Pagination changed. ii This book is dedicated to Charlie Contents Page Disclaimer........................................................................................................................... ii Foreword............................................................................................................................ vi About the author .............................................................................................................. -

What's Inside

TAKE ONE! June 2014 Paving the path to heritage WHAT’S INSIDE President’s message . 2 SHA memorials, membership form . 10-11 Picture this: Midsummer Night . 3 Quiz on Scandinavia . 12 Heritage House: New path, new ramp . 4-5 Scandinavian Society reports . 13-15 SHA holds annual banquet . 6-7 Tracing Scandinavian roots . 16 Sutton Hoo: England’s Scandinavian connection . 8-9 Page 2 • June 2014 • SCANDINAVIAN HERITAGE NEWS President’s MESSAGE Scandinavian Heritage News Vol. 27, Issue 67 • June 2014 Join us for Midsummer Night Published quarterly by The Scandinavian Heritage Assn . by Gail Peterson, president man. Thanks to 1020 South Broadway Scandinavian Heritage Association them, also. So far 701/852-9161 • P.O. Box 862 we have had sev - Minot, ND 58702 big thank you to Liz Gjellstad and eral tours for e-mail: [email protected] ADoris Slaaten for co-chairing the school students. Website: scandinavianheritage.org annual banquet again. Others on the Newsletter Committee committee were Lois Matson, Ade - Midsummer Gail Peterson laide Johnson, Marion Anderson and Night just ahead Lois Matson, Chair Eva Goodman. (See pages 6 and 7.) Our next big event will be the Mid - Al Larson, Carroll Erickson The entertainment for the evening summer Night celebration the evening Jo Ann Winistorfer, Editor consisted of cello performances by Dr. of Friday, June 20, 2014. It is open to 701/487-3312 Erik Anderson (MSU Professor of the public. All of the Nordic country [email protected] Music) and Abbie Naze (student at flags will be flying all over the park. Al Larson, Publisher – 701/852-5552 MSU). -

FRENCH in MALTA Official Programme for Re-Enactments

220TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FRENCH IN MALTA Official Programme for Re-enactments - www.hrgm.org Day Time Event Place Name Description Location Tue, 05 June 10:30 Battle Floriana Maltese sortie against the French and are ambushed Portes de Bombes, Floriana - adjacent woodland 12:30 Parade Valletta Maltese & French forces march into the city Starts at City Gate, ends Palace Square 19:00 Parade Mosta French march through the town ending with short display Starts at Speranza Chapel 19:00 Parade Gharghur Call to arms against the French Main square 20:00 Activities Naxxar Re-enactors enjoy an eve of food, drink, music, songs, & dance Main square Wed, 06 June 16:30 Battle Mistra Bay French landing at Mistra Bay and fight their way to advance Starts at Mistra end at Selmun 20:30 Activities Mellieha Re-enactors enjoy an eve of food, drink, music, songs, & dance Main square Thu, 07 June 10:00 Open Day Birgu From morning till late night - Army garrison life Fort St Angelo 17:15 Parade Bormla Maltese Army short ceremony followed by march to Birgu Next to Rialto Theatre 17:30 Parade Birgu French Army marches to Birgu main square Starts at Fort St Angelo, ends in Birgu main square 17:45 Ceremony Birgu Maltese & French Armies salute eachother; march to St Angelo Birgu main square Fri, 08 June 16:30 Battle Chadwick Lakes French attacked near Chadwick Lakes on the way to Mdina Chadwick Lakes - extended area 18:00 March Mtarfa Maltese start retreat up to Mtarfa with French in pursuit Chadwick Lakes in the vicinity of Mtarfa 18:45 Battle Mtarfa Fighting continues at Mtarfa Around the Clock Tower area 20:00 Battle Rabat Fighting resumes at Rabat. -

A Companion to Nineteenth- Century Britain

A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108, Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, Melbourne, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Chris Williams to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A companion to nineteenth-century Britain / edited by Chris Williams. p. cm. – (Blackwell companions to British history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-22579-X (alk. paper) 1. Great Britain – History – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Great Britain – Civilization – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Williams, Chris, 1963– II. Title. III. Series. DA530.C76 2004 941.081 – dc22 2003021511 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10 on 12 pt Galliard by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO BRITISH HISTORY Published in association with The Historical Association This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of the scholarship that has shaped our current understanding of British history. -

PDF Download Malta, 1565

MALTA, 1565: LAST BATTLE OF THE CRUSADES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tim Pickles,Christa Hook,David Chandler | 96 pages | 15 Jan 1998 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781855326033 | English | Osprey, United Kingdom Malta, 1565: Last Battle of the Crusades PDF Book Yet the defenders held out, all the while waiting for news of the arrival of a relief force promised by Philip II of Spain. After arriving in May, Dragut set up new batteries to imperil the ferry lifeline. Qwestbooks Philadelphia, PA, U. Both were advised by the yearold Dragut, the most famous pirate of his age and a highly skilled commander. Elmo, allowing Piyale to anchor his fleet in Marsamxett, the siege of Fort St. From the Publisher : Highly visual guides to history's greatest conflicts, detailing the command strategies, tactics, and experiences of the opposing forces throughout each campaign, and concluding with a guide to the battlefields today. Meanwhile, the Spaniards continued to prey on Turkish shipping. Tim Pickles describes how despite constant pounding by the massive Turkish guns and heavy casualties, the Knights managed to hold out. Michael across a floating bridge, with the result that Malta was saved for the day. Michael, first with the help of a manta similar to a Testudo formation , a small siege engine covered with shields, then by use of a full-blown siege tower. To cart. In a nutshell: The siege of Malta The four-month Siege of Malta was one of the bitterest conflicts of the 16th century. Customer service is our top priority!. Byzantium at War. Tim Pickles' account of the siege is extremely interesting and readable - an excellent book. -

EUI Working Papers

ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2010/75 ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUDO Citizenship Observatory DUAL CITIZENSHIP FOR TRANSBORDER MINORITIES? HOW TO RESPOND TO THE HUNGARIAN-SLOVAK TIT-FOR-TAT Edited by Rainer Bauböck EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUROPEAN UNION DEMOCRACY OBSERVATORY ON CITIZENSHIP Dual citizenship for transborder minorities? How to respond to the Hungarian-Slovak tit-for-tat EDITED BY RAINER BAUBÖCK EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2010/75 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © 2010 Edited by Rainer Bauböck Printed in Italy, October 2010 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), created in 1992 and directed by Stefano Bartolini since September 2006, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research and to promote work on the major issues facing the process of integration and European society. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes and projects, and a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration and the expanding membership of the European Union. -

![Demesne Arable Farming in Coastal Sussex During the Later Middle Ages ,:I!:I/,] :!; L by P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3737/demesne-arable-farming-in-coastal-sussex-during-the-later-middle-ages-i-i-l-by-p-363737.webp)

Demesne Arable Farming in Coastal Sussex During the Later Middle Ages ,:I!:I/,] :!; L by P

ii!'2~'i' Demesne Arable Farming in Coastal Sussex during the Later Middle Ages ,:i!:i/,] :!; l By P. F. BRANDON N the early fourteenth century only parts of Kent among all the provinces /?::'. :ii !i/i] of England exceeded the wealth of coastal Sussex. 1 The prosperity of this I tract was derived from many sources but its primary basis lay in its sheep- and-corn farming which rested upon exceptionally favourable physical condi- tions, easy access to tide-water, and close proximity to markets in maritime England and on the Continent. ~The quality of its flock management, the wide- spread substitution of a legume course for bare fallow, and densely sown fields producing grain yields higher than the medieval norm placed it firmly in the vanguard of the agricultural development of its day. The agrarian institutions •)] chiefly responsible for this unusually high level of technical efficiency were manors of the classical type of Seebohm and Vinogradoff, with large demesnes "2; and bodies of dependent cultivators, grouped into extensive honours and //I archiepiscopal, episcopal, and monastic lordships. They functioned, par ex- cellence, as 'federated grain factories' during the period of intensive demesne j::, _ exploitation, and gave the tract both social and geographical coherence. :i. | Indeed, they dominated its economy by the immense scale of their operations/ largely conducted with increasing flexibility within consolidated demesnes which were separated from the tounmanneslonds, the attenuated common fields of the servile tenants. The origins of the agrarian conditions within these manors have long in- voked an enquiry which shows no sign of abatement, ~ but little attention has 1 F. -

The Three Cities

18 – The Three Cities The Three Cities are Vittoriosa/Birgu, Cospicua/Bormla and Senglea/L’Isla. Most of the Three Cities was badly bombed, much of its three parts destroyed, during the Second World War. Some inkling of what the area went through is contained in Chapter 15. Much earlier, it had been bombarded during the Great Siege of 1565, as described in Chapter 5, which also tells how Birgu grew from a village to the vibrant city of the Order of the Knights of St John following their arrival in 1530. You cannot travel to the other side of the Grand Harbour without bearing those events in mind. And yet, almost miraculously, the Three Cities have been given a new lease of life, partly due to European Union funding. You would really be missing out not to go. Most of the sites concerning women are in Vittoriosa/Birgu. From the Upper Barracca Gardens of Valletta you get a marvellous view of the Three Cities, and I think the nicest way to get there is to take the lift down from the corner of the gardens to the waterfront and cross the road to the old Customs House behind which is the landing place for the regular passenger ferry which carries you across the Grand Harbour. Ferries go at a quarter to and a quarter past the hour, and return on the hour and the half hour. That is the way we went. Guide books suggest how you make the journey by car or bus. If you are taking the south tour on the Hop-On Hop-Off bus, you could hop off at the Vittoriosa waterfront (and then hop on a later one). -

Layout VGD Copy

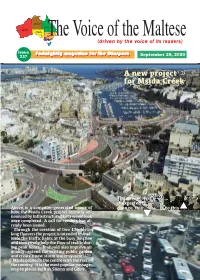

The Voic(edr iivoenf b yt thhe evo iicMe of aiitsl retaedesrse ) Issue FFoorrttnniigghhttllyy mmaaggaazziinnee ffoorr tthhee DDiiaassppoorraa September 2 237 9, 2020 AA nneeww pprroojjeecctt ffoorr MMssiiddaa CCrreeeekk The new project q is expected to Above is a computer-generated image of change this ....to this how the Msida Creek project recently an - nounced by Infrastructure Malta would look q once completed. A call for tenders has al - ready been issued. Through the creation of two 175-metre long flyovers the project is intended to erad - icate the traffic lights at the busy junction and immensely help the flow of traffic dur - ing peak hours. It should also improve air quality, extend the existing public garden and create a new storm water system. Msida connects the centre with the rest of the country. It is the most popular passage - way to places such as Sliema and G żira. 2 The Voice of the Maltese Tuesday September 29, 2020 Kummentarju: Il-qawwa tal-istampa miktuba awn iż-żmenijiet tal-pandemija COVID-19 ġabu għal kopji ta’ The Voice. Sa anke kellna talbiet biex magħhom ħafna ċaqlieq u tibdil fil-ħajja, speċjal - imwasslulhom kopja d-dar għax ma jistgħux joħorġu. ment fost dawk vulnerabbl, li fost kollox sabu Kellna wkoll djar tal-anzjani li talbuna kopji. F’każ Dferm aktar ħin liberu. Imma aktar minhekk qed isibu minnhom wassalnielhom kull edizzjoni, u tant ħadu wkoll nuqqas ta’ liberta’. pjacir jaqraw The Voice li sa kien hemm min, fost l-anz - Minħabba r-restrizzjonijiet u għal aktar sigurtá biex jani li ċemplilna biex juri l-apprezzament tiegħu. -

The King's Nation: a Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand

THE KING’S NATION: A STUDY OF THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF NATION AND NATIONALISM IN THAILAND Andreas Sturm Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London (London School of Economics and Political Science) 2006 UMI Number: U215429 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U215429 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and entitled ‘The King’s Nation: A Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand’, represents my own work and has not been previously submitted to this or any other institution for any degree, diploma or other qualification. Andreas Sturm 2 VV Abstract This thesis presents an overview over the history of the concepts ofnation and nationalism in Thailand. Based on the ethno-symbolist approach to the study of nationalism, this thesis proposes to see the Thai nation as a result of a long process, reflecting the three-phases-model (ethnie , pre-modem and modem nation) for the potential development of a nation as outlined by Anthony Smith. -

Conquering the Conqueror at Belgrade (1456) and Rhodes (1480

Conquering the conqueror at Belgrade (1456) and Rhodes (1480): irregular soldiers for an uncommon defense Autor(es): De Vries, Kelly Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/41538 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_30_13 Accessed : 5-Oct-2021 13:38:47 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Kelly DeVries Revista de Historia das Ideias Vol. 30 (2009) CONQUERING THE CONQUEROR AT BELGRADE (1456) AND RHODES (1480): IRREGULAR SOLDIERS FOR AN UNCOMMON DEFENSE(1) Describing Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II's military goals in the mid- -fifteenth century, contemporary Ibn Kemal writes: "Like the world-illuminating sun he succumbed to the desire for world conquest and it was his plan to burn with overpowering fire the agricultural lands of the rebellious rulers who were in the provinces of the land of Rüm [the Byzantine Empire!. -

Source of the Lake: 150 Years of History in Fond Du Lac

SOURCE OF THE LAKE: 150 YEARS OF HISTORY IN FOND DU LAC Clarence B. Davis, Ph.D., editor Action Printing, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin 1 Copyright © 2002 by Clarence B. Davis All Rights Reserved Printed by Action Printing, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin 2 For my students, past, present, and future, with gratitude. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS AND LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PREFACE p. 7 Clarence B. Davis, Ph.D. SOCIETY AND CULTURE 1. Ceresco: Utopia in Fond du Lac County p. 11 Gayle A. Kiszely 2. Fond du Lac’s Black Community and Their Church, p. 33 1865-1943 Sally Albertz 3. The Temperance Movement in Fond du Lac, 1847-1878 p. 55 Kate G. Berres 4. One Community, One School: p. 71 One-Room Schools in Fond du Lac County Tracey Haegler and Sue Fellerer POLITICS 5. Fond du Lac’s Anti-La Follette Movement, 1900-1905 p. 91 Matthew J. Crane 6. “Tin Soldier:” Fond du Lac’s Courthouse Square p. 111 Union Soldiers Monument Ann Martin 7. Fond du Lac and the Election of 1920 p. 127 Jason Ehlert 8. Fond du Lac’s Forgotten Famous Son: F. Ryan Duffy p. 139 Edie Birschbach 9. The Brothertown Indians and American Indian Policy p. 165 Jason S. Walter 4 ECONOMY AND BUSINESS 10. Down the Not-So-Lazy River: Commercial Steamboats in the p. 181 Fox River Valley, 1843-1900 Timothy A. Casiana 11. Art and Commerce in Fond du Lac: Mark Robert Harrison, p. 199 1819-1894 Sonja J. Bolchen 12. A Grand Scheme on the Grand River: p.