PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEEK of PRAYER for CHRISTIAN UNITY and Throughout the Year 2020

IMPORTANT This is the international version of the text of the Week of Prayer 2020 Kindly contact your local Bishops’ Conference or Synod of your Church to obtain an adaptation of this text for your local context Resources for THE WEEK OF PRAYER FOR CHRISTIAN UNITY and throughout the year 2020 THEY SHOWED US UNUSUAL KINDNESS (cf. Acts 28:2) Jointly prepared and published by The Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity The Commission on Faith and Order of the World Council of Churches Scripture quotations: The scripture quotations contained herein are from The New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, 1995, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used with permission. All rights reserved. TO THOSE ORGANIZING THE WEEK OF PRAYER FOR CHRISTIAN UNITY The search for unity: throughout the year The traditional period in the northern hemisphere for the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity is 18-25 January. Those dates were proposed in 1908 by Paul Wattson to cover the days between the feasts of St Peter and St Paul, and therefore have a symbolic significance. In the southern hemisphere where January is a vacation time churches often find other days to celebrate the Week of Prayer, for example around Pentecost (suggested by the Faith and Order movement in 1926), which is also a symbolic date for the unity of the Church. Mindful of the need for flexibility, we invite you to use this material throughout the whole year to express the degree of communion which the churches have already reached, and to pray together for that full unity which is Christ’s will. -

The Sicilian Revolution of 1848 As Seen from Malta

The Sicilian Revolution of 1848 as seen from Malta Alessia FACINEROSO, Ph.D. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Following the Sicilian revolution of 1848, many italian intellectuals and politicalfiguresfound refuge in Malta where they made use ofthe Freedom ofthe Press to divulge their message ofunification to the mainland. Britain harboured hopes ofseizing Sicily to counterbalance French expansion in the Mediterranean and tended to support the legitimate authority rather than separatist ideals. Maltese newspapers reflected these opposing ideas. By mid-1849 the revolution was dead. Keywords: 1848 Sicilian revolution, Italian exiles, Freedom of the Press, Maltese newspapers. The outbreak of Sicilian revolution of 12 January 1848 was precisely what everyone in Malta had been expecting: for months, the press had followed the rebellious stirrings, the spread of letters and subversive papers, and the continuous movements of the British fleet in Sicilian harbours. A huge number of revolutionaries had already found refuge in Malta, I escaping from the Bourbons and anxious to participate in their country's momentous events. During their stay in the island, they shared their life experiences with other refugees; the freedom of the press that Malta obtained in 1839 - after a long struggle against the British authorities - gave them the possibility to give free play to audacious thoughts and to deliver them in writing to their 'distant' country. So, at the beginning of 1848, the papers were happy to announce the outbreak of the revolution: Le nOlizie che ci provengono dalla Sicilia sono consolanti per ta causa italiana .... Era if 12 del corrente, ed il rumore del cannone doveva annunziare al troppo soflerente papalo siciliano it giorno della nascifa def suo Re. -

Muslims in Malta: Avoiding Discrimination

MUSLIMS IN MALTA: AVOIDING DISCRIMINATION CAROL GATT (WORLD ISLAMIC CALL SOCIETY) Introduction Equality is crucial to the European Union’s survival. It is a very ambitious project to try joining all the existing mentalities and ‘mainstreams’ of Europe but this will not hold if the Union does not promote true justice, for the weak and for the strong. The people need to feel proud of belonging to the Union. This will only take place if and when the European Union really causes justice to dominate, and teaches all to love it and respect it at the same time. Equality is not a bureaucratic concept in the minds of the people. The members of a civilised society demand it in many practical ways and it is the government’s obligation that it be afforded to all. Equality for the weaker in society will, in the end, make all people feel safer, for ‘majorities’ will not be afraid of minorities and those who are not mainstream, knowing that all will have justice meted out to them and that all must be respected. Knowing that equality is available for the weaker and the most vulnerable of society will let the majority population perceive that as individuals they also can be guaranteed their slice of justice if ever they need it. Equality has to be the backbone of the European Union. It is what will keep the Union together in the end- the surety that justice and as a result, true equality, will rule in the end be it between the large countries and the smaller ones, between the richer countries and the poorer, between the fairer and the darker people of the European Union, between the Christians, the Muslims, the Jews and all other people of good will. -

Confirmations Text and Audio Version, Visit “To Celebrate a Shepherd’S God’S Grace

25 days for A farewell 25 years to arms Diocesan family A lecture offers spiritual on nuclear bouquets for bishop, disarmament with page 3. Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, page 3. www.ErieRCD.org BI-WEEKLY NEWS BULLETIN OF THE DIOCESE OF ERIE May 2, 2010 Church Calendar Events of the local, American and universal church ing,” the congregation gave Bishop Trautman a warm and Feast days Diocese celebrates extended ovation during the entrance procession. Walking Bishop Trautman’s down the cathedral’s main aisle, the bishop greeted well- anniversaries wishers with waves and hel- los. By Jason Koshinskie In his homily, Bishop Traut- FaithLife editor man said God’s grace given to an individual is a grace for the ERIE – Affirming that his spiritual welfare of all God’s double anniversary was not a people. celebration about one person, In a light moment, the bish- St. Matthias St. Isidore Bishop Donald Trautman re- op referenced his battle over called the words of Pope Leo the new English translation of the Roman Missal, which he May 1 St. Joseph the Worker the Great. In 444 while preaching on has publicly critiqued. May 3 St. Philip and St. James the anniversary of his own “St. Paul stresses the same episcopal ordination, Pope Photo by Tim Rohrbach thought in his Letter to young May 6 National Day of Prayer Leo the Great said, “To cel- Timothy: ‘It is not because ebrate a shepherd’s anniver- dral in Erie marking his 25th anniversary as Rigali of Philadelphia, nearly 200 hundred anything we have done, but it May 10 Blessed Damien Joseph de Veuster sary is to honor the whole a bishop and 20th anniversary as bishop of priests from both the dioceses of Erie and was according to his own pur- of Moloka’i flock.” Erie. -

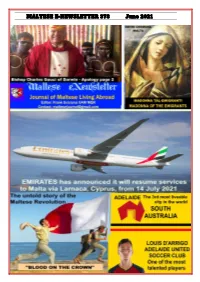

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 Aboriginal survivors reach settlement with Church, Commonwealth cathnew.com Survivors of Aboriginal forced removal policies have signed a deal for compensation and apology 40 years after suffering sexual and physical abuse at the Garden Point Catholic Church mission on Melville Island, north of Darwin. Source: ABC News. “I’m happy, and I’m sad for the people who have gone already … we had a minute’s silence for them … but it’s been very tiring fighting for this for three years,” said Maxine Kunde, the leader Mgr Charles Gauci - Bishop of Darwin of a group of 42 survivors that took civil action against the church and Commonwealth in the Northern Territory Supreme Court. At age six, Ms Kunde, along with her brothers and sisters, was forcibly taken from her mother under the then-federal government’s policy of removing children of mixed descent from their parents. Garden Point survivors, many of whom travelled to Darwin from all over Australia, agreed yesterday to settle the case, and Maxine Kunde (ABC News/Tiffany Parker) received an informal apology from representatives of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, in a private session.Ms Kunde said members of the group were looking forward to getting a formal public apology which they had been told would be delivered in a few weeks’ time. Darwin Bishop Charles Gauci said on behalf of the diocese he apologised to those who were abused at Garden Point. -

The Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty

4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature By Olivia Snaije July 24, 2017 Wit (13) Besides the fact that it’s a beautiful island in the middle of the Mediterranean, how much do we really know about Malta? You may remember it's where the Knights of Malta spent some time between the 16th and the 18th century. Comic book https://www.bookwitty.com/text/malta-the-struggle-to-preserve-language-and/596f7cb050cef766f8f236ab 1/11 4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty aficionados will be familiar with the fact that Joe Sacco was born in Malta. But did you know, for example, that in 2018 the island will be the European Capital of Culture? Or that every August a literature festival is held there? And that three Maltese authors, Immanuel Mifsud, Pierre J. Mejlak, and Walid Nabhan recently won the European Prize for Literature? The language they write in, of course, is Maltese, which is derived from an Arabic dialect that was spoken in Sicily and Spain during the Middle Ages. It sounds like Arabic with a smattering of Italian and English thrown in, and it is written in Latin script, making it the only Semitic language to be inscribed this way. A page from Il Cantilena https://www.bookwitty.com/text/malta-the-struggle-to-preserve-language-and/596f7cb050cef766f8f236ab 2/11 4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty A 15th century poem called “Il Cantilena”, by Petrus Caxaro is the earliest written document in Maltese that has been preserved. -

St-Paul-Faith-Iconography.Pdf

An exhibition organized by the Sacred Art Commission in collaboration with the Ministry for Gozo on the occasion of the year dedicated to St. Paul Exhibition Hall Ministry for Gozo Victoria 24th January - 14th February 2009 St Paul in Art in Gozo c.1300-1950: a critical study Exhibition Curator Fr. Joseph Calleja MARK SAGONA Introduction Artistic Consultant Mark Sagona For many centuries, at least since the Late Middle Ages, when Malta was re- Christianised, the Maltese have staunchly believed that the Apostle of the Gentiles Acknowledgements was delivered to their islands through divine intervention and converted the H.E. Dr. Edward Fenech Adami, H.E. Tommaso Caputo, inhabitants to Christianity, thus initiating an uninterrupted community of 1 Christians. St Paul, therefore, became the patron saint of Malta and the Maltese H.E. Bishop Mario Grech, Hon. Giovanna Debono, called him their 'father'. However, it has been amply and clearly pointed out that the present state of our knowledge does not permit an authentication of these alleged Mgr. Giovanni B. Gauci, Arch. Carmelo Mercieca, Arch. Tarcisio Camilleri, Arch. Salv Muscat, events. In fact, there is no historic, archaeological or documentary evidence to attest Arch. Carmelo Gauci, Arch. Frankie Bajada, Arch. Pawlu Cardona, Arch. Carmelo Refalo, to the presence of a Christian community in Malta before the late fourth century1, Arch. {u\epp Attard, Kapp. Tonio Galea, Kapp. Brian Mejlaq, Mgr. John Azzopardi, Can. John Sultana, while the narrative, in the Acts of the Apostles, of the shipwreck of the saint in 60 AD and its association with Malta has been immersed in controversy for many Fr. -

A Literary Translation in the Making

A LITERARY TRANSLATION IN THE MAKING An in-depth investigation into the process of a literary translation from French into Maltese CLAUDINE BORG Doctor of Philosophy ASTON UNIVERSITY October 2016 © Claudine Borg, 2016 Claudine Borg asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this thesis This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without appropriate permission or acknowledgement. 1 ASTON UNIVERSITY Title: A literary translation in the making: an in-depth investigation into the process of a literary translation from French into Maltese Name: Claudine Borg Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Date: 2016 Thesis summary: Literary translation is a growing industry with thousands of texts being published every year. Yet, the work of literary translators still lacks visibility and the process behind the emergence of literary translations remains largely unexplored. In Translation Studies, literary translation was mostly examined from a product perspective and most process studies involved short non- literary texts. In view of this, the present study aims to contribute to Translation Studies by investigating in- depth how a literary translation comes into being, and how an experienced translator, Toni Aquilina, approached the task. It is particularly concerned with the decisions the translator makes during the process, the factors influencing these and their impact on the final translation. This project places the translator under the spotlight, centring upon his work and the process leading to it while at the same time exploring a scantily researched language pair: French to Maltese. -

Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta

Vol:1 No.1 2003 96-118 www.educ.um.edu.mt/jmer Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta George Cassar [email protected] George Cassar holds the post of lecturer with the University of Malta. He is Area Co- ordinator for the Humanities at the Junior College where he is also Subject Co-ordinator in- charge of the Department of Sociology. He holds degrees from the University of Malta, obtaining his Ph.D. with a thesis entitled Prelude to the Emergence of an Organised Teaching Corps. Dr. Cassar is author of a number of articles and chapters, including ‘A glimpse at private education in Malta 1800-1919’ (Melita Historica, The Malta Historical Society, 2000), ‘Glimpses from a people’s heritage’ (Annual Report and Financial Statement 2000, First International Merchant Bank Ltd., 2001) and ‘A village school in Malta: Mosta Primary School 1840-1940’ (Yesterday’s Schools: Readings in Maltese Educational History, PEG, 2001). Cassar also published a number of books, namely, Il-Mużew Marittimu Il-Birgu - Żjara edukattiva għall-iskejjel (co-author, 1997); Għaxar Fuljetti Simulati għall-użu fit- tagħlim ta’ l-Istorja (1999); Aspetti mill-Istorja ta’ Malta fi Żmien l-ingliżi: Ktieb ta’ Riżorsi (2000) (all Għaqda ta’ l-Għalliema ta’ l-Istorja publications); Ġrajja ta’ Skola: L-Iskola Primarja tal-Mosta fis-Sekli Dsatax u Għoxrin (1999) and Kun Af il-Mosta Aħjar: Ġabra ta’ Tagħlim u Taħriġ (2000) (both Mosta Local Council publications). He is also researcher and compiler of the website of the Mosta Local Council launched in 2001. Cassar is editor of the journal Sacra Militia published by the Sacra Militia Foundation and member on The Victoria Lines Action Committee in charge of the educational aspects. -

Sexual Morality and Religious Belief Among LGBT and Cohabiting Catholics in Malta and Sicily

Between faith and love? Sexual morality and religious belief among LGBT and cohabiting Catholics in Malta and Sicily University of Malta Library – Electronic Thesis & Dissertations (ETD) Repository The copyright of this thesis/dissertation belongs to the author. The author’s rights in respect of this work are as defined by the Copyright Act (Chapter 415) of the Laws of Malta or as modified by any successive legislation. Users may access this full-text thesis/dissertation and can make use of the information contained in accordance with the Copyright Act provided that the author must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the prior permission of the copyright holder. Between faith and love? Sexual morality and religious belief among LGBT and cohabiting Catholics in Malta and Sicily A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Malta Angele Deguara 2018 ii To the beautiful people of the LGBT community and to those who dare be themselves iii ABSTRACT My ethnographic study explores the role of religion in relation to intimate relationships in contemporary Maltese society and to a lesser extent in Palermo, Sicily. The study examines the intersection between faith and sexuality in a secularising society. It seeks to answer two main research questions: (i) whether and to what extent the Catholic Church and its teaching influence the lifestyles, decisions, beliefs and behaviours of individuals in intimate relationships; (ii) how Catholics who are in sexual relationships which do not conform to the moral guidelines of the Catholic Church, more specifically lesbian, gay, bisexual or trans (LGBT) and divorced or separated and cohabiting or remarried men and women experience conflict arising from the incongruence between their beliefs and their sexual desires or lifestyle choices. -

Influence of National Culture on Diabetes

Influence of national culture on diabetes education in Malta: A case example Cynthia Formosa, Kevin Lucas, Anne Mandy, Carmel Keller Article points Diabetes is a condition of particular importance to the 1. This study aimed to Maltese population. Currently, 10% of the Maltese population explore whether or has diabetes, compared with 2–5% of the population in not diabetes education the majority of Malta’s neighbouring European nations improved knowledge, HbA1c and cholesterol (Rocchiccioli et al, 2005). The high prevalence of diabetes levels in Maltese people results in nearly one out of every four deaths of Maltese people with type 2 diabetes. occurring before the age of 65 years (Cachia, 2003). In this 2. There was no difference article we explore the possible contributions of the unique between the intervention and control groups in Maltese culture to the epidemiology, we hope that some lessons any of the metabolic can be taken when attempting educational interventions in parameters. people of differing backgrounds. 3. Sophisticated programmes that take account of the unique nature of Maltese culture are necessary to he reasons why Malta has such a high living conditions started to improve for ordinary bring about behavioural incidence and prevalence of diabetes Maltese people (Savona-Ventura, 2001). and metabolic changes in are complex. The Maltese population Extensive social disruption was brought this group. T Key words is the result of the inter-marrying between about by lengthy blockades that occurred peoples of the various cultures and nations during the Second World War, resulting in - Education that have occupied the island through the ages. -

THE COINS of MUSLIM MALTA Helen W

THE COINS OF MUSLIM MALTA Helen W. Brown In 1976 an attempt was made to study the coins from the period of the Muslim occupation of Malta and Gozo surviving in the public and in certain private collections on the islands. I am grateful to Dr Anthony Luttrell for instigating and facilitating this enterprise and for providing the study of the Mdina Hoard published in the article below. The friendly interest and co-operation of the museum curators is warmly acknowledged, and special thanks are due to the private collectors who provided help and information. The following collections were examined: National Museum of Archaeology, Valletta Gozo Museum Cathedral Museum, Mdina Museum of the Missionary Society of St. Paul, Rabat Mr. Joseph Attard Mr. Emanuel Azzopardi, Valletta Mr. Antoine Debono, Rabat Hon. Mr. Justice A.J. Montanaro Gauci, Valletta Chevalier John Sant Manduca, Mdina Mr. Roger Vella Bonavita, Attard Anonymous Collector, Vall etta. Several other collectors, among whose coins no pieces of immediate concern to the project were found, were generous with their time, and their help too is gratefully acknowledged. Outside Malta, enquiries were made at the Venerable Order of St. John of Jerusalem, St. John's Gate, Clerkenwell in London, and a gift of coins made to the British Museum in 1965 was also examined. Finally, three hoard groups of supreme interest and importance were considered: the great Mdina Hoard of gold coins, almost all melted down immediately, and surviving only in the description of Ciantar, the only substantial body of material whose Maltese provenance is authenticated beyond any doubt; a group of about 140 pieces, mostly of very base silver, the property of the National Museum; and another, similar, group, the property of a private collector.