The Language and Literature of Malta: a Synthesis of Semitic and Latin Elements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo

A CLASS ACADEMY OF ENGLISH BELS GOZO EUROPEAN SCHOOL OF ENGLISH (ESE) INLINGUA SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES St. Catherine’s High School, Triq ta’ Doti, ESE Building, 60, Tigne Towers, Tigne Street, 11, Suffolk Road, Kercem, KCM 1721 Paceville Avenue, Sliema, SLM 3172 Mission Statement Pembroke, PBK 1901 Gozo St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Tel: (+356) 2010 2000 Tel: (+356) 2137 4588 Tel: (+356) 2156 4333 Tel: (+356) 2137 3789 Email: [email protected] The mission of the ELT Council is to foster development in the ELT profession and sector. Malta Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.inlinguamalta.com can boast that both its ELT profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being Web: www.aclassenglish.com Web: www.belsmalta.com Web: www.ese-edu.com practically the only language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school maintains a national quality standard. All this has resulted in rapid growth for INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH the sector. ACE ENGLISH MALTA BELS MALTA EXECUTIVE TRAINING LANGUAGE STUDIES Bay Street Complex, 550 West, St. Paul’s Street, INSTITUTE (ETI MALTA) Mattew Pulis Street, Level 4, St.George’s Bay, St. Paul’s Bay ESE Building, Sliema, SLM 3052 ELT Schools St. Julian’s, STJ 3311 Tel: (+356) 2755 5561 Paceville Avenue, Tel: (+356) 2132 0381 There are currently 37 licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo. Malta can boast that both its ELT Tel: (+356) 2713 5135 Email: [email protected] St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Email: [email protected] profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being the first and practically only Email: [email protected] Web: www.belsmalta.com Tel: (+356) 2379 6321 Web: www.ielsmalta.com language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school Web: www.aceenglishmalta.com Email: [email protected] maintains a national quality standard. -

The Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty

4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature By Olivia Snaije July 24, 2017 Wit (13) Besides the fact that it’s a beautiful island in the middle of the Mediterranean, how much do we really know about Malta? You may remember it's where the Knights of Malta spent some time between the 16th and the 18th century. Comic book https://www.bookwitty.com/text/malta-the-struggle-to-preserve-language-and/596f7cb050cef766f8f236ab 1/11 4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty aficionados will be familiar with the fact that Joe Sacco was born in Malta. But did you know, for example, that in 2018 the island will be the European Capital of Culture? Or that every August a literature festival is held there? And that three Maltese authors, Immanuel Mifsud, Pierre J. Mejlak, and Walid Nabhan recently won the European Prize for Literature? The language they write in, of course, is Maltese, which is derived from an Arabic dialect that was spoken in Sicily and Spain during the Middle Ages. It sounds like Arabic with a smattering of Italian and English thrown in, and it is written in Latin script, making it the only Semitic language to be inscribed this way. A page from Il Cantilena https://www.bookwitty.com/text/malta-the-struggle-to-preserve-language-and/596f7cb050cef766f8f236ab 2/11 4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty A 15th century poem called “Il Cantilena”, by Petrus Caxaro is the earliest written document in Maltese that has been preserved. -

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 235 September 2018 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 235 September 2018 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 235 September 2018 President inaugurates meditation garden at Millennium Chapel President of Malta Marie-Louise Coleiro Preca officially inaugurated ‘The Word’ – the new meditation garden at the Millennium Chapel. President Coleiro Preca expressed her hope that this garden will be used by many people who are seeking refuge and peace in today’s uncertain world, and that they will be transformed by its atmosphere of contemplation and tranquillity. “Whilst I would like to commend the Millennium Chapel team for their dedication and hard work, in particular Fr Hilary Tagliaferro and his collaborators on this project, including Richard England, Duncan Polidano, Noel Attard, and Peter Calamatta, I am confident that the Millennium Chapel will continue to provide essential support and care for all the people who walk through its doors”, the President said. The Millennium Chapel The Millennium Chapel is run by a Foundation of lay volunteers and forms part of the Augustinian Province of Malta. Professional people and volunteers, called “Welcomers” are participating in the operation and day to day running of the Chapel and WoW (Wishing Others Well). The Chapel is open from 8.00 a.m. to 2.00 a.m. all the year round except Good Friday. You, too, may offer your time and talent to bring peace and love in the heart of the entertainment life of Malta, or may send a small contribution so that this mission may continue in the future. In the heart of the tourist and entertainment centre of Malta’s nightlife there stands an oasis of peace :- THE MILLENNIUM CHAPEL and WOW , (Wishing Others Well), These are two pit stops in the hustle and bustle of Paceville – considered the mecca of young people and foreign tourists who visit the Island of Malta. -

Layout VGD Copy

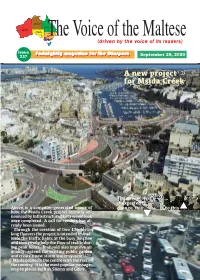

The Voic(edr iivoenf b yt thhe evo iicMe of aiitsl retaedesrse ) Issue FFoorrttnniigghhttllyy mmaaggaazziinnee ffoorr tthhee DDiiaassppoorraa September 2 237 9, 2020 AA nneeww pprroojjeecctt ffoorr MMssiiddaa CCrreeeekk The new project q is expected to Above is a computer-generated image of change this ....to this how the Msida Creek project recently an - nounced by Infrastructure Malta would look q once completed. A call for tenders has al - ready been issued. Through the creation of two 175-metre long flyovers the project is intended to erad - icate the traffic lights at the busy junction and immensely help the flow of traffic dur - ing peak hours. It should also improve air quality, extend the existing public garden and create a new storm water system. Msida connects the centre with the rest of the country. It is the most popular passage - way to places such as Sliema and G żira. 2 The Voice of the Maltese Tuesday September 29, 2020 Kummentarju: Il-qawwa tal-istampa miktuba awn iż-żmenijiet tal-pandemija COVID-19 ġabu għal kopji ta’ The Voice. Sa anke kellna talbiet biex magħhom ħafna ċaqlieq u tibdil fil-ħajja, speċjal - imwasslulhom kopja d-dar għax ma jistgħux joħorġu. ment fost dawk vulnerabbl, li fost kollox sabu Kellna wkoll djar tal-anzjani li talbuna kopji. F’każ Dferm aktar ħin liberu. Imma aktar minhekk qed isibu minnhom wassalnielhom kull edizzjoni, u tant ħadu wkoll nuqqas ta’ liberta’. pjacir jaqraw The Voice li sa kien hemm min, fost l-anz - Minħabba r-restrizzjonijiet u għal aktar sigurtá biex jani li ċemplilna biex juri l-apprezzament tiegħu. -

A Literary Translation in the Making

A LITERARY TRANSLATION IN THE MAKING An in-depth investigation into the process of a literary translation from French into Maltese CLAUDINE BORG Doctor of Philosophy ASTON UNIVERSITY October 2016 © Claudine Borg, 2016 Claudine Borg asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this thesis This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without appropriate permission or acknowledgement. 1 ASTON UNIVERSITY Title: A literary translation in the making: an in-depth investigation into the process of a literary translation from French into Maltese Name: Claudine Borg Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Date: 2016 Thesis summary: Literary translation is a growing industry with thousands of texts being published every year. Yet, the work of literary translators still lacks visibility and the process behind the emergence of literary translations remains largely unexplored. In Translation Studies, literary translation was mostly examined from a product perspective and most process studies involved short non- literary texts. In view of this, the present study aims to contribute to Translation Studies by investigating in- depth how a literary translation comes into being, and how an experienced translator, Toni Aquilina, approached the task. It is particularly concerned with the decisions the translator makes during the process, the factors influencing these and their impact on the final translation. This project places the translator under the spotlight, centring upon his work and the process leading to it while at the same time exploring a scantily researched language pair: French to Maltese. -

Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta

Vol:1 No.1 2003 96-118 www.educ.um.edu.mt/jmer Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta George Cassar [email protected] George Cassar holds the post of lecturer with the University of Malta. He is Area Co- ordinator for the Humanities at the Junior College where he is also Subject Co-ordinator in- charge of the Department of Sociology. He holds degrees from the University of Malta, obtaining his Ph.D. with a thesis entitled Prelude to the Emergence of an Organised Teaching Corps. Dr. Cassar is author of a number of articles and chapters, including ‘A glimpse at private education in Malta 1800-1919’ (Melita Historica, The Malta Historical Society, 2000), ‘Glimpses from a people’s heritage’ (Annual Report and Financial Statement 2000, First International Merchant Bank Ltd., 2001) and ‘A village school in Malta: Mosta Primary School 1840-1940’ (Yesterday’s Schools: Readings in Maltese Educational History, PEG, 2001). Cassar also published a number of books, namely, Il-Mużew Marittimu Il-Birgu - Żjara edukattiva għall-iskejjel (co-author, 1997); Għaxar Fuljetti Simulati għall-użu fit- tagħlim ta’ l-Istorja (1999); Aspetti mill-Istorja ta’ Malta fi Żmien l-ingliżi: Ktieb ta’ Riżorsi (2000) (all Għaqda ta’ l-Għalliema ta’ l-Istorja publications); Ġrajja ta’ Skola: L-Iskola Primarja tal-Mosta fis-Sekli Dsatax u Għoxrin (1999) and Kun Af il-Mosta Aħjar: Ġabra ta’ Tagħlim u Taħriġ (2000) (both Mosta Local Council publications). He is also researcher and compiler of the website of the Mosta Local Council launched in 2001. Cassar is editor of the journal Sacra Militia published by the Sacra Militia Foundation and member on The Victoria Lines Action Committee in charge of the educational aspects. -

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 329 July 2020

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 329 July 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 329 July 2020 FRANK SCICLUNA RETIRES… I WOULD LIKE INFORM MY READERS that I am retiring from the office of honorary consul for Malta in South Australia after 17 years of productive and sterling work for the Government of the Republic of Malta. I feel it is the appropriate time to hand over to a new person. I was appointed in May 2003 and during my time as consul I had the privilege to work with and for the members of the Maltese community of South Australia and with all the associations and especially with the Maltese Community Council of SA. I take this opportunity to sincerely thank all my friends and all those who assisted me in my journey. My dedication and services to the community were acknowledged by both the Australian and Maltese Governments by awarding me with the highest honour – Medal of Order of Australia and the medal F’Gieh Ir-Repubblika, which is given to those who have demonstrated exceptional merit in the service of Malta or of humanity. I thank also the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Evarist Bartolo, for acknowledging my continuous service to the Government of the Republic of Malta. I plan to continue publishing this Maltese eNewsletter – the Journal of Maltese Living Abroad which is the most popular and respected journal of the Maltese Diaspora and is read by thousands all over the world. I will publish in my journal the full story of this item in the near future. MS. CARMEN SPITERI On 26 June 2020 I was appointed as the Honorary Consul for Malta in South Australia. -

Malta in Context by J.M. Ruggier. Journal Of

MALTA IN CONTEXT A Survey of Language and Litetatun "Infinite riches in a little room" Marlowe: Dactar Faustus JOE M. RUGGIER Situated 60 miles to the South ofSicily..,.200 tothe North of North Africa, measuring a mere 117 square miles in all, and for 200 years a British Colony, Malta is an island museum at the crosst0ad8 ofthe Meiliterranean. a treasure house of tradition, culture, history and prehistory. ExcIuding migrants, the present population exceeds 300,000 and thepopulationdensity is among the highest anywhere. Semitic in their origins, Europeafi. through their apprenticesrup, the Maltese were converted to Christianity by St. Paul in A.D. 60. The faith has been to the inhabitants of these islands tbe unifying po'Wer which, like a rod of Moses, has made of three barren rocks a nation with a character. Sufficiently isolated from their European and Semitic neighbours, and taking apride in their Crusoe-like isolation, the Maltese have always had to rely on their own resources, and have even developed autonomous language. It has, of course, been impossible for Maltese not to import much specialized, modern, and not-so-modern jargon, and before Homer wrote, I suppose, Greek was probably a poorer language than Maltese is nowadays. What does it sound Iike? That part of the vocabulary which the Maltese regard as pure Maltese is of Semitic origin, and sounds Semitic, while that part of the vocabulary which the Maltese regard to be imported, has come from the Romance Ianguages, Spanish, Freoch, mostly Italian, and some English terros, and either sounds Latinate, or English. -

THE LANGUAGE QUESTION in MALTA - the CONSCIOUSNESS of a NATIONAL IDENTITY by OLIVER FRIGGIERI

THE LANGUAGE QUESTION IN MALTA - THE CONSCIOUSNESS OF A NATIONAL IDENTITY by OLIVER FRIGGIERI The political and cultural history of Malta is largely determined by her having been a colony, a land seriously limited in her possibilities of acquiring self consciousness and of allowing her citizens to live in accordance with their own aspirations. Consequently the centuries of political submission may be equally defined as an uninterrupted experience of cultural submission. In the long run it has been a benevolent and fruitful submission. But culture, particularly art, is essentially a form of liberation. Lack of freedom in the way of life, therefore, resulted in lack of creativity. Nonetheless her very insularity was to help in the formation of an indigenous popular culture, segregated from the main foreign currents, but necessarily faithful to the conditions of the simple life of the people, a predominantly rural anrl nilioio115 life taken up by preoccupations of a subdued rather than rebellious nature, concerned with the family rather than with the nation. The development of the two traditional languages of Malta - the Italian language, cultured and written, and the Maltese, popular and spoken - can throw some light on this cultural and social dualism. The geographical position and the political history of the island brought about a very close link with Italy. In time the smallness of the island found its respectable place in the Mediterranean as European influence, mostly Italian, penetrated into the country and, owing to isolation, started to adopt little by little the local original aspects. The most significant factor of this phenomenon is that Malta created a literary culture (in its wider sense) written in Italian by the Maltese themselves. -

Livret Malte

A la conquê te de... Malte La Valette Carte d’identité Connais-tu le drapeau maltais ? • La superficie de Malte est de 316 km². 316 km² A C Saviez-vous • Le territoire maltais est un archipel situé au centre de la que...? mer Méditerranée, entre l’Afrique du Nord et le sud de l’Europe. B D • La capitale du pays est La Valette. Réponse : • Malte compte une population de 400 000 habitants, sa densité est la plus élevée de l’Union européenne. • L’hymne maltais a été créé en 1922. Ses paroles, à l’origine une prière dédiée à 400 000 la nation maltaise soulignant son attachement profond à cette terre, ont été habitants 2 écrites par Dun Karm Psaila, le plus célèbre des poètes maltais. La musique a été composée par Robert Samut. 3 • La monnaie du pays est l’euro, depuis janvier 2008. • Malte est une République parlementaire fortement inspirée du système hérité de la période coloniale britannique. • Malte a deux langues officielles, l’Anglais et le Maltais. Bongu ! • Du côté de l’exécutif, le président est élu pour cinq ans par la Chambre des représentants à la majorité absolue et il nomme le Premier ministre. S’agissant du pouvoir législatif, la Chambre des représentants est le Parlement unicaméral de • Deux spécialités culinaires maltes : Malte. Elle compte 65 députés élus pour cinq ans. Fenkata, lapin cuisiné en ragoût. L’histoire de ce plat ? On raconte qu’il ète la phrase ! s’agit d’une forme de résistance à l’époque des «Chevaliers de malte», ompl lorsqu’à leur arrivée ceux-ci imposèrent des restrictions concernant la C chasse au lapin. -

A Mysterious Book by Mikiel Anton Vassalli?

GIOVANNI BONELLO A MYSTERIOUS BOOK BY MIKIEL ANTON VASSALLI? An important book on Malta, published anonymously in Paris in 1798, may be the work of Mikiel Anton Vassalli, the father of Maltese nationhood. Shortly after Napoleon captured Malta in June 1798, a French editor, C.F. Cramer, printed a historical and political 'Michelin' of Malta: Recherches Historiques et Politiques sur Malte par···. There was a pressing need for such a publication, as very little about Malta was currently available in French at that time. The author, who was definitely Maltese, wanted with his book to demonstrate his "devotion and admiration for France, and his affection for his native land" 1. Although Malta had not been legally incorporated into the French jurisdiction, he believed that, "in the common interest of the two nations, the Maltese would soon clamour for union with France,,2. The identity of the anonymous author of these Recherches has remained shrouded in mystery. Charles Wilkinson, an intelligent visitor to Malta, writing in 1804, obviously admired the book and translated into English large portions of it, without hazarding a guess as to its authorship 3. So did many other authors 4 . Attributed to Onorato Bres As far as I have been able to establish, it was only in 1885 that Ferdinand De Hellwald's Bibliographie5 first attributed the Recherches to Onorato Bres6. Hellwald, an erudite bookworm, refers to no authority in support of his attribution to Bres. Though Hellwald's bibliography is certainly invaluable, it is hardly always infallible. This attribution of the Recherches to Bres is very suspect. -

26 November 2020

Circulated in more than 145 States to personalities in the legal and maritime professions IMLIe-News The IMO International Maritime Law Institute Official Electronic Newsletter (Vol.18, Issue No.16) 26 November 2020 IMLI MOURNS WITH MALTA THE DEATH OF PROFESSOR OLIVER FRIGGIERI The IMO International Maritime Law Institute wishes to express its heartfelt condolences to the Maltese people and the family and friends of Professor Oliver Friggieri, who died on Saturday 21 November 2020 at the age of 73 years. He was a Professor of Maltese at the University of Malta and has been described as a giant of Maltese literature, an intellectual, poet, novelist and critic, whose work defined a canon of Maltese national literature. Professor Oliver Friggieri An intellectual who was a poet, novelist, literary critic, and philosopher, his work had an unmistakable timbre of existentialism. He articulated Malta’s national consciousness in his works, notably with his 1986 work Fil- Parlament ma Jikbrux Fjuri. Professor Friggieri was born in Floriana, Malta, in 1947. He studied at the Bishop’s Seminary and then at the University of Malta in 1968 where he acquired a Bachelor of Arts in Maltese, Italian and Philosophy (1968), and then a Masters (1975). He began his career in 1968 teaching Maltese and Philosophy in secondary schools. In 1978 he acquired a Doctorate in Maltese literature and Literary Criticism from the Catholic University of Milan, Italy. In 1976, he started lecturing Maltese to the University of Malta, before being appointed head of department in 1988. Professor Friggier became Professor in 1990. Between 1970 and 1971 he was active in Malta’s literary revival movement, the Moviment Qawmien Letterarju.