Romano-Arabica XIV, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Harvard University

THE CENTER FOR MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES, NEWS HARVARD UNIVERSITY SPRING 2015 1 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR A message from William Granara 2 SHIFTING TOWARDS THE ARABIAN PENINSULA Announcing a new lecture series 3 NEWS AND NOTES Updates from faculty, students and visiting researchers 12 EVENT HIGHLIGHTS Spring lectures, workshops, and conferences LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR SPRING 2015 HIGHLIGHTS I’M HAPPY TO REPORT THAT WE ARE DRAWING TO THE CLOSE OF AN ACADEMIC YEAR FULL OF ACTIVITY. CMES was honored to host a considerable number of outstanding lectures this year by eminent scholars from throughout the U.S. as well as from the Middle East and Europe. I mention only a few highlights below. Our new Middle Eastern Literatures initiative was advanced by several events: campus visits by Arab novelists Mai Nakib (Kuwait), Ahmed Khaled Towfik (Egypt), and Ali Bader (Iraq); academic lectures by a range of literary scholars including Hannan Hever (Yale) on Zionist literature and Sheida Dayani (NYU) on contemporary Persian theater; and a highly successful seminar on intersections between Arabic and Turkish literatures held at Bilgi University in Istanbul, which included our own Professor Cemal Kafadar, several of our graduate students, and myself. In early April, CMES along with two Harvard Iranian student groups hosted the first Harvard Iranian Gala, which featured a lecture by Professor Abbas Milani of Stanford University and was attended by over one hundred guests from the broader Boston Iranian community. Also in April, CMES co-sponsored an international multilingual conference on The Thousand and One Nights with INALCO, Paris. Our new Arabian Peninsula Studies Lecture Series was inaugurated with a lecture by Professor David Commins of Dickinson College, and we are happy to report that this series will continue in both the fall and spring semesters of next year thanks to the generous support of CMES alumni. -

Kuwaiti Arabic: a Socio-Phonological Perspective

Durham E-Theses Kuwaiti Arabic: A Socio-Phonological Perspective AL-QENAIE, SHAMLAN,DAWOUD How to cite: AL-QENAIE, SHAMLAN,DAWOUD (2011) Kuwaiti Arabic: A Socio-Phonological Perspective, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/935/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Kuwaiti Arabic: A Socio-Phonological Perspective By Shamlan Dawood Al-Qenaie Thesis submitted to the University of Durham for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures 2011 DECLARATION This is to attest that no material from this thesis has been included in any work submitted for examination at this or any other university. i STATEMENT OF COPYRIGHT The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Arabic Sociolinguistics: Topics in Diglossia, Gender, Identity, And

Arabic Sociolinguistics Arabic Sociolinguistics Reem Bassiouney Edinburgh University Press © Reem Bassiouney, 2009 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh Typeset in ll/13pt Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and East bourne A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 2373 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 2374 7 (paperback) The right ofReem Bassiouney to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Contents Acknowledgements viii List of charts, maps and tables x List of abbreviations xii Conventions used in this book xiv Introduction 1 1. Diglossia and dialect groups in the Arab world 9 1.1 Diglossia 10 1.1.1 Anoverviewofthestudyofdiglossia 10 1.1.2 Theories that explain diglossia in terms oflevels 14 1.1.3 The idea ofEducated Spoken Arabic 16 1.2 Dialects/varieties in the Arab world 18 1.2. 1 The concept ofprestige as different from that ofstandard 18 1.2.2 Groups ofdialects in the Arab world 19 1.3 Conclusion 26 2. Code-switching 28 2.1 Introduction 29 2.2 Problem of terminology: code-switching and code-mixing 30 2.3 Code-switching and diglossia 31 2.4 The study of constraints on code-switching in relation to the Arab world 31 2.4. 1 Structural constraints on classic code-switching 31 2.4.2 Structural constraints on diglossic switching 42 2.5 Motivations for code-switching 59 2. -

FOREIGNER TALK in ARABIC Input in Circumstances Such As Those

CHAPTER SIX FOREIGNER TALK IN ARABIC Input in circumstances such as those illustrated in chapter four took place by means of modifying the target language (i.e. tendencies of Foreigner Talk). Because Arabs, as the native speakers of the target language, were the majority group in the loci of early communica- tion, they themselves were able to undertake the initiative of modify- ing their native language, especially when the majority of them were monolinguals. Although heavy restructuring and loaning from a for- eign language have permanently affected the formation of varieties of Arabic elsewhere in East Africa and Asia, the type of input and the non-linguistic ecological conditions that facilitated it in the now-Arab world inhibited this process in the case of the dialects. It is unlikely, according to the conclusion of the previous chapter, that native speak- ers undertake a heavy restructuring of their language, even if the purpose is educational. If heavy restructuring is attempted by native speakers it takes place in highly marked situations. When restructur- ing occurs, however, the upgrading nature of FT does not allow a per- manent mark on the output of the non-native speaker. Generally speaking, if FT should be grammatical, and if the con- clusions concerning the socio-demographics of Arabicization have any historical truth, then it must be responsible for the differences between Classical Arabic (as the nearest variety to pre-Islamic Arabic) and the Modern Arabic dialects. These differences are less than the differences between Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic on the one hand and the Arabic-based pidgins and creoles on the other, but are in many respects the result of internal processes, such as gen- eralization and reduction. -

Bediuzzaman Said Nursi and Risale-I

YUHİB Bediuzzaman Said Nursi and Risale-i Nur Editor: Erhan Akkaya [email protected] Proofreading: Yeni Asya English Team Graphic Designer: Mücahit Ak [email protected] Address: Gülbahar Caddesi, 1508 Sokak, No: 3, 34212 Güneşli, Istanbul Tel : +90 212 655 88 60 (Pbx) Fax : +90 212 651 92 09 e-mail : [email protected] [email protected] Contact Address: Yeni Asya Eğitim Kültür ve Araştırma Vakfı Cemal Yener Tosyalı Cad. No: 61, Vefa, Süleymaniye - Fatih, Istanbul Tel : +90 212 5131110 e-mail : [email protected] This publication is sponsored by YUHİB. What is Risale-i Nur? Who is Bediuzzaman Said Nursi? Said Nursi was born in 1878 in a village known as Nurs, within the borders of the town of Hizan, 3 and the city of Bitlis in the Eastern part of Turkey. He died on 23 March 1960 in Şanlıurfa, a city in the Southeastern Turkey. Said Nursi, having a keen mind, an extraordi nary memory, and outstanding abilities had drawn the attentions upon himself since his childhood. He completed his education in the traditional madras ah system in a very short time about three months, which takes many years to complete under normal conditions. His youth passed with an active pur suit of education and his superiority at knowledge and science was evident in the discussions with the scholars of the time on different occasions. Said Nursi who had made himself with his capacity and Who is Bediuzzaman Said Nursi? abilities accepted in the scientific and intellectual circles has begun to be called Bediuzzaman, “the wonder of the age”. -

International Bureau for Children's Rights (IBCR)

Making Children’s Rights Work in North Africa: Country Profiles on Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco Country Profiles on Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia and Tunisia Making Children’s Rights Work in North Africa:Making Children’s Rights Work Making Children’s Rights Work in North Africa: Country Profiles on Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia The first version of this report was posted on IBCR’s website in March 2007. This second version has been reedited in August 2007. International Bureau for Children’s Rights (IBCR) Created in 1994 and based in Montreal, Canada, the International Bureau for Children’s Rights (IBCR) is an international non- governmental organisation (INGO) with special consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). IBCR offers its expertise, particularly in the legal sector, to contribute to the protection and promotion of children’s rights in conformity with the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and its Optional Protocols. The expertise of IBCR resides in the sharing of knowledge and good practices and in the development of tools and models to inspire implementation of children’s rights. IBCR’s expertise also lies in raising awareness about children’s rights to persuade decision-makers to adopt laws and programmes that more effectively respect the rights of the child. In recent years, IBCR’s main successes include its exceptional contribution to the elaboration of the Guidelines on Justice in Matters Involving Child Victims and Witnesses of Crime as well as their adoption by the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC Res. -

Layout VGD Copy

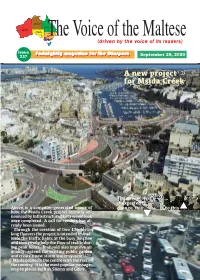

The Voic(edr iivoenf b yt thhe evo iicMe of aiitsl retaedesrse ) Issue FFoorrttnniigghhttllyy mmaaggaazziinnee ffoorr tthhee DDiiaassppoorraa September 2 237 9, 2020 AA nneeww pprroojjeecctt ffoorr MMssiiddaa CCrreeeekk The new project q is expected to Above is a computer-generated image of change this ....to this how the Msida Creek project recently an - nounced by Infrastructure Malta would look q once completed. A call for tenders has al - ready been issued. Through the creation of two 175-metre long flyovers the project is intended to erad - icate the traffic lights at the busy junction and immensely help the flow of traffic dur - ing peak hours. It should also improve air quality, extend the existing public garden and create a new storm water system. Msida connects the centre with the rest of the country. It is the most popular passage - way to places such as Sliema and G żira. 2 The Voice of the Maltese Tuesday September 29, 2020 Kummentarju: Il-qawwa tal-istampa miktuba awn iż-żmenijiet tal-pandemija COVID-19 ġabu għal kopji ta’ The Voice. Sa anke kellna talbiet biex magħhom ħafna ċaqlieq u tibdil fil-ħajja, speċjal - imwasslulhom kopja d-dar għax ma jistgħux joħorġu. ment fost dawk vulnerabbl, li fost kollox sabu Kellna wkoll djar tal-anzjani li talbuna kopji. F’każ Dferm aktar ħin liberu. Imma aktar minhekk qed isibu minnhom wassalnielhom kull edizzjoni, u tant ħadu wkoll nuqqas ta’ liberta’. pjacir jaqraw The Voice li sa kien hemm min, fost l-anz - Minħabba r-restrizzjonijiet u għal aktar sigurtá biex jani li ċemplilna biex juri l-apprezzament tiegħu. -

![No. 3[28]/2008](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9739/no-3-28-2008-549739.webp)

No. 3[28]/2008

ROMANIA NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY “CAROL I” CENTRE FOR DEFENCE AND SECURITY STRATEGIC STUDIES No. 3[28]/2008 68-72 Panduri Street, sector 5, Bucharest, Romania Telephone: (021) 319.56.49; Fax: (021) 319.55.93 E-mail: [email protected]; Web address: http://impactstrategic.unap.ro, http://cssas.unap.ro NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY “CAROL I” PRINTING HOUSE BUCHAREST, ROMANIA The Centre for Defence and Security Strategic Studies’ scientific quarterly magazine acknowledged by the National University Research Council as a B+ magazine Editorial Board: Marius Hanganu, Professor, Ph.D., president Constantin Moştoflei, Senior Researcher, Ph.D., executive president, editor-in-chief Nicolae Dolghin, Senior Researcher, Ph.D. Hervé Coutau-Bégarie, director, Ph.D. (Institute for Compared Strategy, Paris, France) John L. Clarke, Professor, Ph.D. (European Centre for Security Studies “George C. Marshall”) Adrian Gheorghe, Professor Eng., Ph.D. (Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia, USA) Josef Procházka, Ph.D.����������������������������������������������� (Institute for Strategic Studies, Defence University, Brno, Czech Republic) Dario Matika, Ph.D. (Institute for Research and Development of Defence Systems, Zagreb, Croatia) Gheorghe Văduva, Senior Researcher, Ph.D. Ion Emil, Professor, Ph.D. Editors: Vasile Popa, Researcher Corina Vladu George Răduică Scientific Board: Mihai Velea, Professor, Ph.D. Grigore Alexandrescu, Senior Researcher, Ph.D. The authors are responsible for their articles’ content, respecting the provisions of the Law no. 206 from -

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi To cite this version: Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi. Arabic and Contact-Induced Change. 2020. halshs-03094950 HAL Id: halshs-03094950 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03094950 Submitted on 15 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language Contact and Multilingualism 1 science press Contact and Multilingualism Editors: Isabelle Léglise (CNRS SeDyL), Stefano Manfredi (CNRS SeDyL) In this series: 1. Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). Arabic and contact-induced change. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language science press Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). 2020. Arabic and contact-induced change (Contact and Multilingualism 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/235 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution -

Enhancing the Rule of Law and Guaranteeing Human Rights in the Constitution

Enhancing the Rule of Law and guaranteeing human rights in the Constitution A report on the constitutional reform process in Tunisia Composed of 60 eminent judges and lawyers from all regions of the world, the International Commission of Jurists promotes and protects human rights through the Rule of Law, by using its unique legal expertise to develop and strengthen national and international justice systems. Established in 1952 and active on the five continents, the ICJ aims to ensure the progressive development and effective implementation of international human rights and international humanitarian law; secure the realization of civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights; safeguard the separation of powers; and guarantee the independence of the judiciary and legal profession. Cover photo © Copyright Remi OCHLIK/IP3 © Copyright International Commission of Jurists The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) permits free reproduction of extracts from any of its publications provided that due acknowledgment is given and a copy of the publication carrying the extract is sent to its headquarters at the following address: International Commission Of Jurists P.O. Box 91 Rue des Bains 33 Geneva Switzerland Enhancing the Rule of Law and guaranteeing human rights in the Constitution TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND KEY RECOMMENDATIONS ................................... 2 CHRONOLOGY................................................................................................ 8 GLOSSARY .................................................................................................... -

1 Arab Studies at the University of Bucharest Ovidiu Pietrăreanu

Arab studies at the University of Bucharest Ovidiu Pietrăreanu © 2015 The beginning of the study of Arabic at university level in Romania goes back to the sixth decade of the twentieth century, as the Arabic language department of the University of Bucharest was founded in 1957, against the backdrop of more far-reaching developments that Romania was witnessing at that time, out of which the most closely related to the decision of founding a department for the study and teaching of Arabic was the striving of the then Romanian authorities for strengthening the country’s relations with states that seemed to them more in line with their own political orientations, such as those belonging to the Socialist Bloc or the Non-Aligned Movement, which the Arab states joined in that same period. All these factors had an important part to play in turning Romania’s attention towards vast areas falling outside what was conventionally known as the Western world, and this in turn has led, in the sphere of education, to the creation of a chair of oriental languages within the Faculty of Letters which, besides the Arabic department, also comprises departments assigned for languages like Chinese, Turkish etc. Afterwards a faculty of foreign languages and literatures, separated from the Faculty of Letters, was created, and thus the Arabic department has acquired a new administrative umbrella. In both faculties, however, foreign languages have been taught according to a system requiring from each student to simultaneously study two languages as primary and secondary specializations, and Arabic has always been taught, with the exception of a period in the eighties of the last century, as a primary specialization. -

Tunisia: Freedom of Expression Under Siege

Tunisia: Freedom of Expression under Siege Report of the IFEX Tunisia Monitoring Group on the conditions for participation in the World Summit on the Information Society, to be held in Tunis, November 2005 February 2005 Tunisia: Freedom of Expression under Siege CONTENTS: Executive Summary p. 3 A. Background and Context p. 6 B. Facts on the Ground 1. Prisoners of opinion p. 17 2. Internet blocking p. 21 3. Censorship of books p. 25 4. Independent organisations p. 30 5. Activists and dissidents p. 37 6. Broadcast pluralism p. 41 7. Press content p. 43 8. Torture p. 46 C. Conclusions and Recommendations p. 49 Annex 1 – Open Letter to Kofi Annan p. 52 Annex 2 – List of blocked websites p. 54 Annex 3 – List of banned books p. 56 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) is a global network of 64 national, regional and international freedom of expression organisations. This report is based on a fact-finding mission to Tunisia undertaken from 14 to 19 January 2005 by members of the IFEX Tunisia Monitoring Group (IFEX-TMG) together with additional background research and Internet testing. The mission was composed of the Egyptian Organization of Human Rights, International PEN Writers in Prison Committee, International Publishers Association, Norwegian PEN, World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters (AMARC) and World Press Freedom Committee. Other members of IFEX-TMG are: ARTICLE 19, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE), the Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Studies (CEHURDES), Index on Censorship, Journalistes en Danger (JED), Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA), and World Association of Newspapers (WAN).