Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thoroton Society Publications

THOROTON SOCIETY Record Series Blagg, T.M. ed., Seventeenth Century Parish Register Transcripts belonging to the peculiar of Southwell, Thoroton Society Record Series, 1 (1903) Leadam, I.S. ed., The Domesday of Inclosures for Nottinghamshire. From the Returns to the Inclosure Commissioners of 1517, in the Public Record Office, Thoroton Society Record Series, 2 (1904) Phillimore, W.P.W. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. I: Henry VII and Henry VIII, 1485 to 1546, Thoroton Society Record Series, 3 (1905) Standish, J. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. II: Edward I and Edward II, 1279 to 1321, Thoroton Society Record Series, 4 (1914) Tate, W.E., Parliamentary Land Enclosures in the county of Nottingham during the 18th and 19th Centuries (1743-1868), Thoroton Society Record Series, 5 (1935) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem and other Inquisitions relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. III: Edward II and Edward III, 1321 to 1350, Thoroton Society Record Series, 6 (1939) Hodgkinson, R.F.B., The Account Books of the Gilds of St. George and St. Mary in the church of St. Peter, Nottingham, Thoroton Society Record Series, 7 (1939) Gray, D. ed., Newstead Priory Cartulary, 1344, and other archives, Thoroton Society Record Series, 8 (1940) Young, E.; Blagg, T.M. ed., A History of Colston Bassett, Nottinghamshire, Thoroton Society Record Series, 9 (1942) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Bonds and Allegations for Marriage Licenses in the Archdeaconry Court of Nottingham, 1754-1770, Thoroton Society Record Series, 10 (1947) Blagg, T.M. -

Bourgogne and Its Five Wine-Producing Regions

Bourgogne and its five wine-producing regions Dijon Nancy Chenôve CHABLIS, GRAND AUXERROIS & CHÂTILLONNAIS Marsannay-la-Côte CÔTE DE NUITS A 31 Couchey Canal de Bourgogne Fixin N 74 Gevrey-Chambertin Troyes Ource N 71 Morey-St-Denis Seine Chambolle-Musigny Hautes Côtes Vougeot Charrey- Belan- Gilly-lès-Cîteaux sur-Ource de Nuits Vosne-Romanée Flagey-Échezeaux Molesmes sur-Seine Massingy Paris Nuits-St-Georges Premeaux-Prissey D 980 A 6 Comblanchien Laignes Châtillon-sur-Seine Corgoloin Pernand-Vergelesses Tonnerre Ladoix-Serrigny CÔTE DE BEAUNE Montbard Aloxe-Corton Dijon Savigny-lès-Beaune Saulieu Chorey-lès-Beaune A 36 Besançon A 31 Hautes Côtes Pommard Troyes Beaune Troyes St-Romain Volnay Paris Armançon de Beaune N 6 Auxey- Monthélie Duresses Meursault Serein Joigny Yonne Puligny- Jovinien Ligny-le-Châtel Montrachet Épineuil St-Aubin Paris Villy Maligny Chassagne-Montrachet A 6 Lignorelles Fontenay- Tonnerre La Chapelle- près-Chablis Dezize-lès-Maranges Santenay Vaupelteigne Tonnerrois Chagny Poinchy Fyé Collan Sampigny-lès-Maranges CÔTE CHALONNAISE Beines Fleys Cheilly-lès-Maranges Bouzeron Milly N 6 Chablis Béru Viviers Dijon Auxerre Chichée Rully A 6 Courgis Couches Chitry Chemilly- Poilly-sur-Serein Mercurey Vaux Préhy St-Bris- sur-Serein Couchois Dole le-Vineux Chablisien St-Martin N 73 Noyers-sur-Serein sous-Montaigu Coulanges- Irancy A 6 Dracy-le-Fort la-Vineuse Canal du Centre Chalon-sur-Saône Cravant Givry Auxerrois Val-de- Nitry Mercy Vermenton Le Creusot r N 80 Clamecy Dijon Lyon Buxy Vézelien Montagny-lès-Buxy Saône Jully- -

Renaissance Studies

398 Reviews of books Denley observes that the history of the Studio dominates not only the historiography of education in Siena but also the documentary series maintained by various councils and administrators in the late medieval and Renaissance eras. The commune was much more concerned about who taught what at the university level than at the preparatory level. Such an imbalance is immediately evident when comparing the size of Denley’s own two studies. Nevertheless, he has provided a useful introduction to the role of teachers in this important period of intellectual transition, and the biographical profiles will surely assist other scholars working on Sienese history or the history of education. University of Massachusetts-Lowell Christopher Carlsmith Christopher S. Wood, Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008. 416 pp. 116 black and white illustrations. Cloth $55.00. ISBN 022-6905977 (hb). Did Germany have a Renaissance? The answer depends, of course, on one’s definition of Renaissance; whether one sees it mainly as an era of rebirth of the arts in imitation of the masters of classical antiquity or not. In Germany, the Romans stayed only in part of what is now the Bundesrepublik Deutschland, while a large Germania Libera (as the Romans called it) continued with her rustic but wholesome customs described by Tacitus as an example to his fellow countrymen. The Roman influence on Germanic lifestyle was limited and transitory and therefore a rebirth of classical antiquity could only be a complicated one. Not even the Italian peninsula had a homogeneous Roman antiquity (and it would be difficult to give precise chronological and geographical definitions of antiquity per se) but in the case of German Renaissance art the potential models needed to be explored in depth and from an extraneous vantage point. -

Liste Des Communes Du Territoire D'intervention De L'had Sud Yonne

Liste des communes du territoire d’intervention de l’HAD Sud Yonne Accolay Beugnon Chéu Aigremont Bierry-les-Belles-Fontaines Chevannes Aisy-sur-Armançon Billy-sur-Oisy Chevroches Alligny-Cosne Bitry Chichée Amazy Blacy Chitry Ancy-le-Franc Blannay Ciez Ancy-le-Libre Bleigny-le-Carreau Cisery Andryes Bléneau Clamecy Angely Bois-d'Arcy Collan Annay Bouhy Colméry Annay-la-Côte Branches Corvol-l'Orgueilleux Annay-sur-Serein Breugnon Cosne-Cours-sur-Loire Annéot Brèves Coulangeron Annoux Brosses Coulanges-la-Vineuse Appoigny Bulcy Coulanges-sur-Yonne Arbourse Bussières Couloutre Arcy-sur-Cure Butteaux Courcelles Argentenay Carisey Courgis Argenteuil-sur-Armançon Censy Courson-les-Carrières Armes Cessy-les-Bois Coutarnoux Arquian Chablis Crain Arthel Chailley Cravant Arthonnay Chamoux Cruzy-le-Châtel Arzembouy Champcevrais Cry Asnières-sous-Bois Champignelles Cuncy-lès-Varzy Asnois Champlemy Cussy-les-Forges Asquins Champlin Dampierre-sous-Bouhy Athie Champs-sur-Yonne Dannemoine Augy Champvoux Diges Auxerre Charbuy Dirol Avallon Charentenay Dissangis Baon Chasnay Domecy-sur-Cure Bazarnes Chassignelles Domecy-sur-le-Vault Beaumont Chastellux-sur-Cure Dompierre-sur-Nièvre Beaumont-la-Ferrière Châteauneuf-Val-de-Bargis Donzy Beauvilliers Châtel-Censoir Dornecy Beauvoir Châtel-Gérard Dracy Beine Chaulgnes Druyes-les-Belles-Fontaines Bernouil Chemilly-sur-Serein Dyé Béru Chemilly-sur-Yonne Égleny Bessy-sur-Cure Cheney Entrains-sur-Nohain www.hadfrance.fr CH d’Auxerre - 2 Bd de Verdun - 89000 AUXERRE - Tél : 03 86 48 45 96 - Fax : 03 86 48 65 50 -

Schéma Départemental Des Carrières De L'yonne 2012-2021

PRÉFET DE L'YONNE Commission Départementale de la Nature, des Sites et des Paysages Schéma départemental des carrières de l'Yonne 2012-2021 RAPPORT PRÉAMBULE Les activités de traitement et d’extraction de matériaux sont le premier maillon d’une filière économique indispensable au département. L’exploitation des roches meubles reste un élément essentiel de l’offre en matériaux nécessaires au développement des territoires. Toute région bénéficiant dans son sous sol de cette ressource se doit de la gérer dans les principes du développement durable. Outre les emplois directs (environ 500 personnes en 2010), l’activité induit également 1200 emplois locaux parmi les fournisseurs et entreprises sous traitantes (terrassement, transport routier, maintenance des équipements), dont le maintien sur le département est lié aux carrières locales. Par ailleurs, l’activité extractive répond aux besoins majoritairement de proximité, d’activités de transformation (béton, industrie du béton, production d’enrobés bitumineux) ou de construction et d’entretien des routes, de construction de bâtiments qui drainent un nombre important d’entreprises tant artisanales qu’industrielles pour lesquelles les modifications des chaines d’approvisionnement entrainent d’importantes perturbations qu’il est nécessaire d’anticiper et d’accompagner (formulations, adaptation des outils industriels, formation des artisans et des entreprises de mise en œuvre). Si l'importance économique du secteur ne peut être ignorée, en revanche, cette activité extractive ne peut se poursuivre ou se développer sans prendre en compte les préoccupations environnementales, et la nécessité de s'inscrire dans un développement durable par une gestion respectueuse et économe des ressources et une approche intégrée des enjeux eaux et biodiversité. -

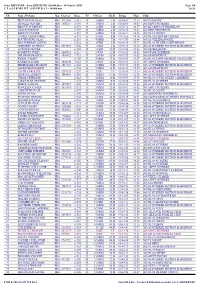

8Ème DIXVIGNE (10.000 Km) - 18 Janvier 2020 Page 1/4 C L a S S E M E N T G E N E R a L - 10.000 Mm 10:31

8ème DIXVIGNE - 8ème DIXVIGNE (10.000 km) - 18 Janvier 2020 Page 1/4 C L A S S E M E N T G E N E R A L - 10.000 mm 10:31 Clt Nom - Prénom Nat Licence Doss. Né Clt Cat Clt Sx Temps Moy. Club 1 PRUVOST NICOLAS FRA1721889 n°314 85 1M0M 1M 00:35:01 17.14 [89] US JOIGNY 2 HISSELLI OLIVIER FRA785619 n°307 78 1M1M 2M 00:36:00 16.67 [89] ASPTT AUXERRE 3 RIBOUTON BENOIT FRA n°476 88 1SEM 3M 00:36:13 16.57 [89] LE CREUSOT TRIATHLON 4 GILLON JORDAN FRA n°220 85 2M0M 4M 00:36:26 16.47 [89] SENS TRIATHLON 5 BRETON OLIVIER FRA n°254 85 3M0M 5M 00:36:41 16.36 [89] NL 89 VENIZY 6 CASTEL CHRISTOPHE FRA n°077 89 2SEM 6M 00:37:09 16.16 [89] NL 89 SAINT BRANCHER 7 BOUTRON NICOLAS FRA n°283 81 4M0M 7M 00:37:47 15.88 [89] AS VILLEMANOCHE 8 MILOT PIERRE-ALEXIS FRA n°222 89 3SEM 8M 00:38:12 15.71 [89] NL 89 VILLIER SAINT BENOIT 9 LEPRETRE ANTHONY FRA2213568 n°306 87 4SEM 9M 00:38:13 15.70 [89] AJ AUXERRE SECTION MARATHON 10 ANTOINE OLIVIER FRA n°422 86 5SEM 10M 00:38:24 15.63 [89] TRAILS YETIS 11 ROSSETTO JULES FRA 1446522 n°111 02 1 JUM 11 M 00:38:25 15.62 [89] STADE AUXERRE 12 DELORME FRANCK FRA1868612 n°324 79 2M1M 12M 00:38:26 15.62 [89] AJ MONETEAU 13 PINEAU CEDRIC FRA n°480 85 5M0M 13M 00:38:33 15.57 [89] NL 89 SAINT GEORGES S/BAULCHE 14 RAMES MATTHIS FRA1686546 n°412 02 2JUM 14M 00:38:33 15.57 [89] ASPTT AUXERRE 15 ZIEJZDZALKA FLORIAN FRA 1618053 n°296 81 6 M0M 15 M 00:38:38 15.54 [89] AJ AUXERRE SECTION MARATHON 16 GAUDICHON FABIEN FRA n°238 84 7M0M 16M 00:38:43 15.50 [89] AJA TRIATHLON 17 TACHE CAROLINE FRA1267335 n°297 86 1SEF 1F 00:38:54 15.43 [89] -

WOF/Winenews F'03 (Page 1)

10" 8.25" Why make every day a Burgun-day? 10.5" 9.75" 10.75" Because Burgundies are “FAB”! 13" Perfect Pairings: F ood-Friendly Burgundy Wines with America’s No need to save the Burgundy for special occasions only. Burgundy pairs perfectly Favorite Foods with the foods you enjoy everyday — and turns ordinary meals into extraordinary. Since these wines range from lighter-bodied to fairly full-bodied, there is a perfect • Caesar salad: white Mâcon or Burgundy match for all the foods you love most. Bourgogne Chardonnay • Sushi, surimi and sashimi: Montagny or Chablis Premier Cru A uthentic • Chilean sea bass: Pouilly-Fuissé or Burgundy, France — the birthplace of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay — has been blessed Meursault with the perfect marriage of soil, climate, grapes and know-how; in a word, terroir. Thanks to this “taste of a place”, each Burgundy has its own unforgettable style, aroma, • Roast chicken: white Beaune or red flavor and charm. And unlike many New World areas, Burgundy is 100% authentic: Bourgogne Hautes Côtes de Nuits 100% Pinot Noir or 100% Chardonnay. • Turkey with stuffing, gravy and cranberry sauce: Mercurey or Volnay • Hamburger and fries: Bourgogne B enchmark Wines Pinot Noir, Bourgogne Hautes Côtes The wines of Burgundy are considered the standard by which all others are judged. de Beaune You’ll find that Burgundies can and will age beautifully, something only wines of the • Sirloin or T-bone steak with creamed highest quality can ever achieve. spinach and garlic mashed potatoes: Gevrey-Chambertin or Fixin Treat yourself to the immediate charms of the wines of Burgundy. -

The Development of Libyan- Tunisian Bilateral Relations: a Critical Study on the Role of Ideology

THE DEVELOPMENT OF LIBYAN- TUNISIAN BILATERAL RELATIONS: A CRITICAL STUDY ON THE ROLE OF IDEOLOGY Submitted by Almabruk Khalifa Kirfaa to the University of Exeter As a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics In December 2014 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: Almabruk Kirfaa………………………………………………………….. i Abstract Libyan-Tunisian bilateral relations take place in a context shaped by particular historical factors in the Maghreb over the past two centuries. Various elements and factors continue to define the limitations and opportunities present for regimes and governments to pursue hostile or negative policies concerning their immediate neighbours. The period between 1969 and 2010 provides a rich area for the exploration of inter-state relations between Libya and Tunisia during the 20th century and in the first decade of the 21st century. Ideologies such as Arabism, socialism, Third Worldism, liberalism and nationalism, dominated the Cold War era, which saw two opposing camps: the capitalist West versus the communist East. Arab states were caught in the middle, and many identified with one side over the other. generating ideological rivalries in the Middle East and North Africa. The anti-imperialist sentiments dominating Arab regimes and their citizens led many statesmen and politicians to wage ideological struggles against their former colonial masters and even neighbouring states. -

St George As Romance Hero

St George as romance hero Article Published Version Fellows, J. (1993) St George as romance hero. Reading Medieval Studies, XIX. pp. 27-54. ISSN 0950-3129 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/84374/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online St George as Romance Hero Jennifer Fellows University of Cambridge The close relationship and interaction between romance and hagiography have, over the past few decades, become a commonplace of the criticism of medieval narrative literature.! Whereas most discussions of this topic deal with the growth of religious idealism in romance, here I shall concentrate rather on the development of hagiography in the direction of rot:nance in the specific case of the legend of 5t George. In a classic series of articles published in the early years of this century, lE. Matzke documented the development of this legend from its earliest known forms to its 'romanticization' in the work of Richard Johnson at the end of the sixteenth century.2 What I wish to do here is to consider in more detail some later forms of the story (from the introduction of the dragon-fight onwards) and, in particular, to reassess the nature of the relationship between the story of St George in Johnson's Seven Champions a/Christendom and the Middle English romance of Sir Bevis 0/ Hampton. -

Dukeries History Trail Booklet

Key Walk 1 P Parking P W Worksop Café Steetley C P P Meals Worksop W Toilets C Manor P M Museum Hardwick Penny Walk 2 Belph Green Walk 7 W C M P W Toll A60 ClumberC B6034 Bothamsall Creswell Crags M Welbeck P W Walk 6 P W M A614 CWalk 3 P Carburton C P Holbeck P P Norton Walk 4 P A616 Cuckney Thoresby P Hall Budby P W M WalkC 5 Sherwood Forest Warsop Country Park Ollerton The Dukeries History Trail SherwoodForestVisitor.com Sherwood Forest’s amazing north 1. Worksop Priory Worksop is well worth a visit as it has a highly accessible town centre with the Priory, Memorial Gardens, the Chesterfield Canal and the old streets of the Town Centre. Like a lot of small towns, if you look, there is still a lot of charm. Park next to the Priory and follow the Worksop Heritage Trail via Priorswell Road, Potter Street, Westgate, Lead Hill and the castle mound, Newcastle Avenue and Bridge Street. Sit in the Memorial Gardens for a while, before taking a stroll along the canal. Visit Mr Straw’s House(National Trust) BUT you must have pre-booked as so many people want to see it. Welbeck Abbey gates, Sparken Hill to the south of the town. The bridge over the canal with its ‘luxury duckhouse’, Priorswell Road . 2. Worksop Manor Lodge Dating from about 1590, the Lodge is a Grade 1 listed building. Five floors have survived – there were probably another two floors as well so would have been a very tall building for its time. -

Historiography of the Crusades

This is an extract from: The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World edited by Angeliki E. Laiou and Roy Parviz Mottahedeh published by Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2001 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America www.doaks.org/etexts.html The Historiography of the Crusades Giles Constable I. The Development of Crusading Historiography The crusades were from their inception seen from many different points of view, and every account and reference in the sources must be interpreted in the light of where, when, by whom, and in whose interests it was written.1 Each participant made his— and in few cases her—own crusade, and the leaders had their own interests, motives, and objectives, which often put them at odds with one another. They were all distrusted by the Byzantine emperor Alexios Komnenos, whose point of view is presented in the Alexiad written in the middle of the twelfth century by his daughter Anna Komnene. The Turkish sultan Kilij Arslan naturally saw things from another perspective, as did the indigenous Christian populations in the east, especially the Armenians, and the peoples of the Muslim principalities of the eastern Mediterranean. The rulers of Edessa, Antioch, Aleppo, and Damascus, and beyond them Cairo and Baghdad, each had their own atti- tudes toward the crusades, which are reflected in the sources. To these must be added the peoples through whose lands the crusaders passed on their way to the east, and in particular the Jews who suffered at the hands of the followers of Peter the Hermit.2 The historiography of the crusades thus begins with the earliest accounts of their origins and history. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'.