Conservation Strategies for Hammams in India Master of Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untitled (Rest) 2018 Viewed Altogether, the Set of Drawings Watercolor on Paper with Sculpture Reveal Patterns and 11.7 X 8.3 Inches Punctuations in Thought

GUIDE III CONTENTS 1 LBF 2 LB01 6 Sites Lahore Fort Mubarak Haveli & Tehsil Park Shahi Hammam Lahore Museum Alhamra Art Centre Bagh-e-Jinnah Canal 134 Academic Forum Academic Forum artSpeak Youth Forum 158 Acknowledgments IV V LAHORE BIENNALE FOUNDATION ﻻہور بینالے فاؤنڈیشن ایک غیر منافع (The Lahore Biennale Foundation (LBF بخش تنظیم ہے ، جو فنی تجربات کے is a non-profit organization that seeks to لئے اہم سائٹس فراہم کرنے اور فن کی provide critical sites for experimentation ممکنہ صﻻحیت کو سماجی تنقید کے in the visual arts. LBF focuses on the لئے آلہ کار بنانے میں کوشاں ہے۔ many stages of production, display فاؤنڈیشن کی توجہ ِعصر حاضر میں and reception of contemporary بنائے جانے والے فن پاروں کی پروڈکشن ، art in diverse forms. It understands نمائش، اور پذیرائی کی متنوع صورتوں inclusivity, collaboration, and public کی طرف مرکوز ہے۔ اسکا مرکزی نقطہ engagement as being central to its نظر سماجی تبدیلیوں کے ایجنٹ کے vision and is committed to developing طور پر عوامی شمولیت، اشتراک ، اور the potential of art as an agent of social فنی صﻻحیتوں کو فروغ دینا ہے۔ اس .transformation مقصد کے لئے فاؤنڈیشن پاکستان بھر میں فنی منصوبوں کی اعانت کر رہی To this end, the LBF endeavors to support ہے خاص طور پر وہ جو تحقیق اور art projects across Pakistan especially تجربے پر مبنی ہیں۔ those critical practices which are based on research and experimentation. LBF ﻻہور بینالے فاؤنڈیشن نے مقامی طور پر ﻻہور بینالے فاونڈیشن is supported by government bodies, ِحکومت پنجاب، کمشنر آفس ﻻہور، پارکس اور ہارٹی کلچر اتھارٹی، اور والڈ and has developed enduring relations سٹی اتھارٹی کے تعاون سے ایک سے with international partners. -

The Place of Performance in a Landscape of Conquest: Raja Mansingh's Akhārā in Gwalior

South Asian History and Culture ISSN: 1947-2498 (Print) 1947-2501 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsac20 The place of performance in a landscape of conquest: Raja Mansingh’s akhārā in Gwalior Saarthak Singh To cite this article: Saarthak Singh (2020): The place of performance in a landscape of conquest: Raja Mansingh’s akhārā in Gwalior, South Asian History and Culture, DOI: 10.1080/19472498.2020.1719756 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2020.1719756 Published online: 30 Jan 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 21 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsac20 SOUTH ASIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2020.1719756 The place of performance in a landscape of conquest: Raja Mansingh’s akhārā in Gwalior Saarthak Singh Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, New York, NY, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In the forested countryside of Gwalior lie the vestiges of a little-known akhārā; landscape; amphitheatre (akhārā) attributed to Raja Mansingh Tomar (r. 1488–1518). performance; performativity; A bastioned rampart encloses the once-vibrant dance arena: a circular stage dhrupad; rāsalīlā in the centre, surrounded by orchestral platforms and an elevated viewing gallery. This purpose-built performance space is a unique monumentalized instance of widely-prevalent courtly gatherings, featuring interpretive dance accompanied by music. What makes it most intriguing is the archi- tectural play between inside|outside, between the performance stage and the wilderness landscape. -

Archaeology Below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan: the Mughal Underground Chambers

Archaeology below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan: The Mughal Underground Chambers Prepared by Rustam Khan For Global Heritage Fund Preservation Fellowship 2011 Acknowledgements: The author thanks the Director and staff of Lahore Fort for their cooperation in doing this report. Special mention is made of the photographer Amjad Javed who did all the photography for this project and Nazir the draughtsman who prepared the plans of the Underground Chambers. Map showing the location of Lahore Walled City (in red) and the Lahore Fort (in green). Note the Ravi River to the north, following its more recent path 1 Archaeology below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan 1. Background Discussion between the British Period historians like Cunningham, Edward Thomas and C.J Rodgers, regarding the identification of Mahmudpur or Mandahukukur with the present city of Lahore is still in need of authentic and concrete evidence. There is, however, consensus among the majority of the historians that Mahmud of Ghazna and his slave-general ”Ayyaz” founded a new city on the remains of old settlement located some where in the area of present Walled City of Lahore. Excavation in 1959, conducted by the Department of Archaeology of Pakistan inside the Lahore Fort, provided ample proof to support interpretation that the primeval settlement of Lahore was on this mound close to the banks of River Ravi. Apart from the discussion regarding the actual first settlement or number of settlements of Lahore, the only uncontroversial thing is the existence of Lahore Fort on an earliest settlement, from where objects belonging to as early as 4th century AD were recovered during the excavation conducted in Lahore Fort . -

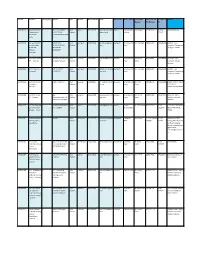

ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Mobile No

ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Mobile No. Of Landline of Address Manager FLC Manager FLC GR09000145 Karpoori Thakur P VILL POST GANDHI Uttar Ballia 9651744234 karpoorithakur1691 Ballia Central Bank N N Kunwar 9415450332 05498- Haldi Kothi,Ballia Dhanushdhari NAGAR TELMA Pradesh @gmail.com of India 225647 Private ITC - JAMALUDDINPUR DISTT Ballia B GR09000192 Sar Sayed School P OHDARIPUR, Uttar Azamgarh 9026699883 govindazm@gmail. Azamgarh Union Bank of Shri R A Singh 9415835509 5462246390 TAMSA F.L.C.C. of Technology RAJAPURSIKRAUR, Pradesh com India Azamgarh, Collectorate, Private ITC - BEENAPARA, Azamgarh, 276001 Binapara - AZAMGARH Azamgarh GR09000314 Sant Kabir Private P Sant Kabir ITI, Salarpur, Uttar Varanasi 7376470615 [email protected] Varanasi Union Bank of Shri Nirmal 9415359661 5422370377 House No: 241G, ITC - Varanasi Rasulgarh,Varanasi Pradesh m India Kumar Ledhupur, Sarnath, Varanasi GR09000426 A.H. Private ITC - P A H ITI SIDHARI Uttar Azamgarh 9919554681 abdulhameeditc@g Azamgarh Union Bank of Shri R A Singh 9415835509 5462246390 TAMSA F.L.C.C. Azamgarh AZAMGARH Pradesh mail.com India Azamgarh, Collectorate, Azamgarh, 276001 GR09001146 Ramnath Munshi P SADAT GHAZIPUR Uttar Ghazipur 9415838111 rmiti2014@rediffm Ghazipur Union Bank of Shri B N R 9415889739 5482226630 UNION BANK OF INDIA Private Itc - Pradesh ail.com India Gupta FLC CENTER Ghazipur DADRIGHAT GHAZIPUR GR09001184 The IETE Private P 248, Uttar Varanasi 9454234449 ietevaranasi@rediff Varanasi Union Bank of Shri Nirmal 9415359661 5422370377 House No: 241G, ITI - Varanasi Maheshpur,Industrial Pradesh mail.com India Kumar Ledhupur, Sarnath, Area Post : Industrial Varanasi GR09001243 Dr. -

Volume 3, 2021 University of Toronto, Graduate Union of Students of Art History

INTAGLIO Volume 3, 2021 University of Toronto, Graduate Union of Students of Art History Beloved Mosque: The Wazir Khan Masjid of Lahore Sanniah Jabeen The Wazir Khan mosque is located in the Walled City of Lahore, along the southern side of Lahore's Shahi Guzargah, or “Royal Road.” This was the traditional route traversed by Mughal nobles and their guests on their way to royal residences at the Lahore Fort. The mosque is situated approximately 260 meters west of the Delhi Gate, where the mosque's Shahi Hammam (Royal Bath) is also located. The mosque faces both a town square, known as Wazir Khan Chowk, and the Chitta (White) Gate. A trip through the Delhi Gate to the Wazir Khan Chowk is an explosion of the senses. If one searches for images of the Delhi Gate Lahore, most incorrectly show the Gate as a wide-open entrance through which vehicles and people can easily pass. If one actually walks through the Delhi Gate, it is absolute chaos. Cars have to be parked many blocks away and visitors have to push through busy cart vendors, donkeys, hens, the occasional cow, as well as young men carrying twice their body weight in fruit, shoes, eatables, and clothing items. The Walled City of Lahore is the only place in the city where human driven carts still exist, as many streets are almost too narrow to allow motor vehicles or even donkey carts. The call for the prayer bellows periodically from the minarets of the Wazir Khan mosque and an increasing cacophony of human chatter, rickshaws, and motorbikes fills the air. -

100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities

100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities A Report Edited by John Dayal ISBN: 978-81-88833-35-1 Suggested Contribution : Rs 100 Published by Anhad INDIA HAS NO PLACE FOR HATE AND NEEDS NOT A TEN-YEAR MORATORIUM BUT AN END TO COMMUNAL AND TARGETTED VIOLENCE AGAINST RELIGIOUS MINORITIES A report on the ground situation since the results of the General Elections were announced on16th May 2014 NEW DELHI, September 27th, 2014 The Prime Minister, Mr. Narendra Modi, led by Bharatiya Janata Party to a resounding victory in the general elections of 2014, riding a wave generated by his promise of “development” and assisted by a remarkable mass mobilization in one of the most politically surcharged electoral campaigns in the history of Independent India. When the results were announced on 16th May 2014, the BJP had won 280 of the 542 seats, with no party getting even the statutory 10 per cent of the seats to claim the position of Leader of the Opposition. The days, weeks and months since the historic victory, and his assuming ofice on 26th May 2014 as the 14th Prime Minister of India, have seen the rising pitch of a crescendo of hate speech against Muslims and Christians. Their identity derided,their patriotism scoffed at, their citizenship questioned, their faith mocked. The environment has degenerated into one of coercion, divisiveness, and suspicion. This has percolated to the small towns and villages or rural India, severing bonds forged in a dialogue of life over the centuries, shattering the harmony build around the messages of peace and brotherhood given us by the Suis and the men and women who led the Freedom Struggle under Mahatma Gandhi. -

Courses in Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2013 Issue 8 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Jaina Logic: Programme 7 Jaina Logic: Abstracts 10 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2012 12 SOAS Workshop 2014: Jaina Hagiography and Biography 13 Jaina Studies at the AAR 2012 16 The Intersections of Religion, Society, Polity, and Economy in Rajasthan 18 DANAM 2012 19 Debate, Argumentation and Theory of Knowledge in Classical India: The Import of Jainism 21 The Buddhist and Jaina Studies Conference in Lumbini, Nepal Research 24 A Rare Jaina-Image of Balarāma at Mt. Māṅgī-Tuṅgī 29 The Ackland Art Museum’s Image of Śāntinātha 31 Jaina Theories of Inference in the Light of Modern Logics 32 Religious Individualisation in Historical Perspective: Sociology of Jaina Biography 33 Daulatrām Plays Holī: Digambar Bhakti Songs of Springtime 36 Prekṣā Meditation: History and Methods Jaina Art 38 A Unique Seven-Faced Tīrthaṅkara Sculpture at the Victoria and Albert Museum 40 Aspects of Kalpasūtra Paintings 42 A Digambar Icon of the Goddess Jvālāmālinī 44 Introducing Jain Art to Australian Audiences 47 Saṃgrahaṇī-Sūtra Illustrations 50 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund Publications 51 Johannes Klatt’s Jaina-Onomasticon: The Leverhulme Trust 52 The Pianarosa Jaina Library 54 Jaina Studies Series 56 International Journal of Jaina Studies 57 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 57 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 58 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 58 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 59 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover Gautama Svāmī, Śvetāmbara Jaina Mandir, Amṛtsar 2009 Photo: Ingrid Schoon 2 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christopher Key Chapple Dr Hawon Ku Professor J. -

Project Profiles for 2016 UNESCO Heritage Award Winners

2016 Project profiles for 2016 UNESCO Heritage Award winners Award of Excellence Project name: Restoration of Sanro-Den Hall at Sukunahikona Shrine in Ozu City Location: Ehime Prefecture, Japan Dramatically perched on a steep slope, the Sanro-Den prayer hall of the highly sacred Sukunahikona Shrine was resurrected in an exemplary act of grassroots mobilization. A rare example of the Kakezukuri architectural style, the building was rescued after two decades of abandonment and has been reintegrated back into the life of the community. With sponsorship from an international foundation, the highest level of quality and authenticity in the conservation work was achieved through the revival of age-old building practices, strict adherence to traditional construction materials and state-of-the-art technical analysis. Advocacy and outreach efforts successfully broadened awareness of the building’s importance among Ozu residents, generating renewed commitment to sustain the shrine for future generations to come. The outpouring of local support from enthusiastic volunteers, experts and skillful artisans serves as a testament to the success of community stewardship in safeguarding vulnerable heritage buildings and fostering cultural continuity. Award of Distinction Project name: Conservation and Restoration of Taoping Qiang Village Location: Sichuan Province, China The restoration of the ancient Taoping Village following the massive 2008 Wenchuan earthquake showcases a holistic approach to community rehabilitation in the wake of a natural disaster. The engagement of ethnic group villagers alongside government agencies, experts and craftspeople throughout the conservation process ensured sensitivity to their Qiang culture in the recovery of the distinctive Diaolou towers, other vernacular architecture, public infrastructure and landscape. -

MHI-10 Urbanisation in India Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Social Sciences

MHI-10 Urbanisation in India Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Social Sciences Block 4 (Part 2) URBANISATION IN MEDIEVAL INDIA-1 UNIT 17 Sultanate and Its Cities 5 UNIT 18 Regional Cities 29 UNIT 19 Temple Towns in Peninsular India 63 UNIT 20 Southern Dimension : The Glory of Vijayanagara 80 UNIT 21 Sultanate Capital Cities in the Delhi Riverine Plain 105 Expert Committee Prof. B.D. Chattopadhyaya Prof. Sunil Kumar Prof. P.K. Basant Formerly Professor of History Department of History Department of History Centre for Historical Studies Delhi University, Delhi Jamia Milia Islamia, New Delhi JNU, New Delhi Prof. Swaraj Basu Prof. Amar Farooqui Prof. Janaki Nair Faculty of History Department of History Centre for Historical Studies IGNOU, New Delhi Delhi University, Delhi JNU, New Delhi Prof. Harbans Mukhia Dr. Vishwamohan Jha Prof. Rajat Datta Formerly Professor of History Atma Ram Sanatan Dharm Centre for Historical Studies Centre for Historical Studies College JNU, New Delhi JNU, New Delhi Delhi University, Delhi Prof. Lakshmi Subramanian Prof. Yogesh Sharma Prof. Abha Singh (Convenor) Centre for Studies in Social Centre for Historical Studies Faculty of History Sciences, Calcutta JNU, New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi Kolkata Prof. Pius Malekandathil Dr. Daud Ali Centre for Historical Studies South Asia Centre JNU, New Delhi University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia Course Coordinator : Prof. Abha Singh Programme Coordinator : Prof. Swaraj Basu Block Preparation Team Unit No. Resource Person Unit No. Resource Person 17 Prof. Abha Singh 19 Prof. Abha Singh Faculty of History Faculty of History School of Social Sciences School of Social Sciences Indira Gandhi National Indira Gandhi National Open University Open University New Delhi New Delhi 20 Dr. -

Winter-Mtg-Jounral-2017-Online.Pdf

Civic Engagement Through Community Service APPNA Association of Physicians of Pakistani Descent of North America 6414 South Cass Avenue, Westmont, IL 60559-3209, USA APPNA Winter Meeting 2017 December 21-23, 2017 Lahore, Pakistan Editorial This year we are celebrating 40th anniversary of APPNA, in these last 40 years our association has morphed into one of the largest ethnic professional society of North America representing over 18000 Pakistan-decent medical graduates from its small humble beginning with just a handful members attending its first meeting in 1976. With every passing year, with every new challenge, opportunity or adversity APPNA has developed even more resilience just like our nation when it comes to dealing with these challenges. Over the years APPNA has taken upon several daunting tasks depending upon the need of the time and strategic vision of its leader. However, no matter who is leading the organization, what kind of political environment or government exit, whenever a calamity hit, APPNA with all the collective strength of its member is always at the forefront of fighting the adversity, regardless if it is in our motherland or adoptive home. Some of the recent examples of excellent relief work APPNA and its members did include help of Tsunami victims in Southeast Asia (2004), Katrina victims in New Orleans, USA and earthquake victims in Pakistan (2005), victims of Sindh Floods (2007) and Pakistan Flood (2010), Thur water well project, Several Free clinics throughout United States, National Health Care Day, Corneal transplants, Fistula surgeries and Cleft Palate surgeries. As a Pakistani medical graduate immigrating to USA, one APPNA characteristic I cherish the most is the platform it has provided to people like myself who want to give back to our motherland and serve their adopted communities. -

Cities, Regions, and Rebels the Impact of Urbanization On

Cities, Regions, and Rebels: The Impact of Urbanization on Conflict in the Developing World Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Cobb, Matthew Ryan Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 06:13:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/641362 CITIES, REGIONS, AND REBELS THE IMPACT OF URBANIZATION ON CONFLICT IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD By Matthew R. Cobb ___________________________ Copyright © Matthew R. Cobb 2020 SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT AND PUBLIC POLICY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by: Matthew Ryan Cobb, titled: Cities, Regions, and Rebels: The Impact of Urbanization on Conflict in the Developing World and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2020 Prof. Alex Braithwaite _________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2020 Prof. Jessica Maves Braithwaite _________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2020 Prof. Jeffrey Kucik _________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2020 Prof. Javier Osorio _________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2020 Prof. Paul Schuler Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Jaunpur Travel Guide Jaunpur District Is Located to the Northwest Of

Jaunpur Travel Guide by traveldesk Jaunpur district is located to the northwest of Varanasi. Jaunpur's history dates from 1388 when the Sultan of Delhi, Feroz Shah Tughlaq, appointed Malik Sarwar, a eunuch, as governor of the region. The Delhi Sultanate was weakened by the 1398 sacking of Delhi by Timur and Malik Sarwar declared independence. Malik Sarwar and his son founded the Sharqi dynasty. During the Sharqi period the Jaunpur Sultanate was a strong military power in Northern India, and on several occasions threatened the Delhi Sultanate. Jaunpur was then a major center of Urdu and Sufi knowledge and culture. Slowly Jaunpur flourished as an important cultural center. Jaunpur's independence came to an end in 1480, when Sikander Lodi, the Sultan of Delhi, conquered the city. The Sharqi kings attempted for several years to retake the city, but ultimately failed. Though the Jaunpur Kingdom did not last long yet it left its mark, particularly, in realms of culture and music. The period saw the construction of many great and beautiful buildings. Although many of the Sharqi monuments were destroyed when the Lodis took the city, several important mosques still remain. The most important one of them are the Atala Masjid, Jama Masjid and the Lal Darwaza Masjid. The Jaunpur mosques display a unique architectural style, combining traditional Hindu and Muslim motifs with purely original elements. The old bridge over the Gomti River dates back to year 1564 AD. Jaunpur Travel Guide by traveldesk.