Conservation of the Shahi Hammam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untitled (Rest) 2018 Viewed Altogether, the Set of Drawings Watercolor on Paper with Sculpture Reveal Patterns and 11.7 X 8.3 Inches Punctuations in Thought

GUIDE III CONTENTS 1 LBF 2 LB01 6 Sites Lahore Fort Mubarak Haveli & Tehsil Park Shahi Hammam Lahore Museum Alhamra Art Centre Bagh-e-Jinnah Canal 134 Academic Forum Academic Forum artSpeak Youth Forum 158 Acknowledgments IV V LAHORE BIENNALE FOUNDATION ﻻہور بینالے فاؤنڈیشن ایک غیر منافع (The Lahore Biennale Foundation (LBF بخش تنظیم ہے ، جو فنی تجربات کے is a non-profit organization that seeks to لئے اہم سائٹس فراہم کرنے اور فن کی provide critical sites for experimentation ممکنہ صﻻحیت کو سماجی تنقید کے in the visual arts. LBF focuses on the لئے آلہ کار بنانے میں کوشاں ہے۔ many stages of production, display فاؤنڈیشن کی توجہ ِعصر حاضر میں and reception of contemporary بنائے جانے والے فن پاروں کی پروڈکشن ، art in diverse forms. It understands نمائش، اور پذیرائی کی متنوع صورتوں inclusivity, collaboration, and public کی طرف مرکوز ہے۔ اسکا مرکزی نقطہ engagement as being central to its نظر سماجی تبدیلیوں کے ایجنٹ کے vision and is committed to developing طور پر عوامی شمولیت، اشتراک ، اور the potential of art as an agent of social فنی صﻻحیتوں کو فروغ دینا ہے۔ اس .transformation مقصد کے لئے فاؤنڈیشن پاکستان بھر میں فنی منصوبوں کی اعانت کر رہی To this end, the LBF endeavors to support ہے خاص طور پر وہ جو تحقیق اور art projects across Pakistan especially تجربے پر مبنی ہیں۔ those critical practices which are based on research and experimentation. LBF ﻻہور بینالے فاؤنڈیشن نے مقامی طور پر ﻻہور بینالے فاونڈیشن is supported by government bodies, ِحکومت پنجاب، کمشنر آفس ﻻہور، پارکس اور ہارٹی کلچر اتھارٹی، اور والڈ and has developed enduring relations سٹی اتھارٹی کے تعاون سے ایک سے with international partners. -

Old-City Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts

Bāzyāft-31 (Jul-Dec 2017) Urdu Department, Punjab University, Lahore 21 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Amjad Parvez ABSTRACT: Lahore has been known as a crucible of diversified cultures owing to its nature of being a trade center, as well as being situated on the path to the capital city Delhi. Both consumers and invaders, played their part in the acculturation of this city from ancient times to the modern era.This research paperinvestigates the existing as well as the vanishing popular culture of the Old-city Lahore. The cuisine, crafts, kites, music, painting and couture of Lahore advocate the assimilation of varied tastes, patterns and colours, with dissimilar origins, within the narrow streets of the Old- city. This document will cover the food, vendors, artisans, artists and the red-light area, not only according to their locations and existence, butin terms of cultural relations too.The paper also covers the distinct standing of Lahore in the South Asia and its popularity among, not only its inhabitants, but also those who ever visited Lahore. Introduction The Old City of Lahore is characterized by the diversity of cultures that is due tovarious invaders and ruling dynasties over the centuries. The narrow streets, dabbed patches of light andunmatched cuisine add to the colours, fragrance and panorama of this unique place. 22 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Figure 1. “Old-city Lahore Street” (2015) By Amjad Parvez Digital Photograph Personal Collection Inside the Old-city Lahore, one may come the steadiness and stationary quality of time, or even one could feel to have been travelled backward in the two or three centuries when things were hand-made, and the culture was non-metropolitan. -

Second Lahore Biennale: Between the Sun and the Moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists

For Immediate Release 6 January 2020 Second Lahore Biennale: between the sun and the moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists Installed Across Cultural and Heritage Sites Throughout Lahore, Pakistan, from 26 January to 29 February 2020 Lahore, Pakistan—6 January 2020—The Lahore Biennale Foundation today revealed a list of over 70 participating artists for the second edition of the Lahore Biennale (LB02), running from 26 January through 29 February 2020. Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, Director of the Sharjah Art Foundation in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, LB02: between the sun and the moon brings a plethora of artistic projects to cultural and heritage sites throughout the city of Lahore including more than 20 new commissions by artists from across the region and around the world, including Alia Farid, Diana Al-Hadid, Hassan Hajjaj, Haroon Mirza, Hajra Waheed and Simone Fattal, among many others. Other participating artists include Anwar Saeed, Rasheed Araeen and the late Madiha Aijaz. With a focus on the Global South, where ongoing social disaffection is being aggravated by climate change, LB02 responds to the cultural and ecological history of Lahore and aims to awaken awareness of humanity’s daunting contemporary predicament. Works presented in LB02 will explore human entanglement with the environment while revisiting traditional understandings of the self and their cosmological underpinnings. Inspiration for this thematic focus is drawn from intellectual and cultural exchange between South and West Asia. “For centuries, inhabitants of these regions oriented themselves with reference to the sun, the moon, and the constellations. -

Archaeology Below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan: the Mughal Underground Chambers

Archaeology below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan: The Mughal Underground Chambers Prepared by Rustam Khan For Global Heritage Fund Preservation Fellowship 2011 Acknowledgements: The author thanks the Director and staff of Lahore Fort for their cooperation in doing this report. Special mention is made of the photographer Amjad Javed who did all the photography for this project and Nazir the draughtsman who prepared the plans of the Underground Chambers. Map showing the location of Lahore Walled City (in red) and the Lahore Fort (in green). Note the Ravi River to the north, following its more recent path 1 Archaeology below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan 1. Background Discussion between the British Period historians like Cunningham, Edward Thomas and C.J Rodgers, regarding the identification of Mahmudpur or Mandahukukur with the present city of Lahore is still in need of authentic and concrete evidence. There is, however, consensus among the majority of the historians that Mahmud of Ghazna and his slave-general ”Ayyaz” founded a new city on the remains of old settlement located some where in the area of present Walled City of Lahore. Excavation in 1959, conducted by the Department of Archaeology of Pakistan inside the Lahore Fort, provided ample proof to support interpretation that the primeval settlement of Lahore was on this mound close to the banks of River Ravi. Apart from the discussion regarding the actual first settlement or number of settlements of Lahore, the only uncontroversial thing is the existence of Lahore Fort on an earliest settlement, from where objects belonging to as early as 4th century AD were recovered during the excavation conducted in Lahore Fort . -

Lahore & Karachi

The Travel Explorers EXPLORE PAKISTAN LAHORE & KARACHI www.thetravelexplorers.com DAY 01 Arrival and meet and greet at Islamabad Airport and then transfer to hotel. Islamabad is the capital and 9th largest city of Pakistan. It is located in the Pothohar Plateau. Islamabad is famous because of its cleanliness, calmness and greenery. Its noise-free atmosphere attracts not only the locals but the foreigners as well. Islamabad has a subtropical climate and one can enjoy all four seasons in this city. Rawalpindi is close to Islamabad and together they are known as the twin cities. In the afternoon half day city tour. We will visit Pakistan Monument located on the Shakarparian Hills in Islamabad. It was established in 2010. This monument serves as the tribute to the people who surrendered their lives and fought for the independence of Pakistan. The monument is of a shape of a blooming flower. There are four large petals which represents the four provinces of Pakistan i.e. Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. There are also three small petals which represents Azad Jammu & Kashmir, FATA and Gilgit Baltistan. There are breathtaking murals on the inner walls of the monument like the murals of Faisal Mosque, Makli Tombs, Gawadar, Quaid-e-Azam, Fatima Jinnah, Badshahi Mosque etc. This monument provides significance of the Pakistani culture, history and lineage. Later we will visit Faisal Mosque which is located near Margalla Hills in Islamabad. It is one of the major tourist attractions in Pakistan. Faisal Bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud granted $120 million in 1976 for the construction of the mosque. -

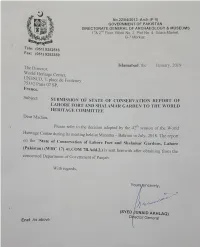

State of Conservation Report by The

Report on State of Conservation of World Heritage Property Fort & Shalamar Gardens Lahore, Pakistan January, 2019 Government of the Punjab Directorate General of Archaeology Youth Affairs, Sports, Archaeology and Tourism Department Table of Contents Sr. Page Item of Description No. No. 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Introduction 3 3. Part-1. Report on decision WHC/18/42.COM/7B.14 5 4. Part-2. Report on State of Conservation of Lahore Fort 13 5. Report on State of Conservation of Shalamar Gardens 37 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Fort & Shalamar Gardens in Lahore, Pakistan were inscribed on the World Heritage List of monuments in 1981. The state of Conservation of the Fort and Shalamar Gardens were discussed in the 42nd Session of the World Heritage Committee (WHC) in July, 2018 at Manama, Bahrain. In that particular session the Committee took various decisions and requested the State Party to implement them and submit a State of Conservation Report to the World Heritage Centre for its review in the 43rd Session of the World Heritage Committee. The present State of Conservation Report consists of two parts. In the first part, progress on the decisions of the 42nd Session of the WHC has been elaborated and the second part of the report deals with the conservation efforts of the State Party for Lahore Fort and Shalamar Gardens. Regarding implementation of Joint World Heritage Centre/ICOMOS Reactive Monitoring Mission (RMM) recommendations, the State Party convened a series of meetings with all the stakeholders including Federal Department of Archaeology, UNESCO Office Islamabad, President ICOMOS Pakistan, various government departments of the Punjab i.e., Punjab Mass-Transit Authority, Lahore Development Authority, Metropolitan Corporation of Lahore, Zonal Revenue Authorities, Walled City of Lahore Authorities, Technical Committee on Shalamar Gardens and eminent national & international heritage experts and deliberated upon the recommendations of the RMM and way forward for their implementation. -

Kamil Khan Mumtaz in Pakistan

A Contemporary Architectural Quest and Synthesis: Kamil Khan Mumtaz in Pakistan by Zarminae Ansari Bachelor of Architecture, National College of Arts, Lahore, Pakistan, 1994. Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1997 Zarminae Ansari, 1997. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. A uthor ...... ................................................................................. .. Department of Architecture May 9, 1997 Certified by. Attilio Petruccioli Aga Khan Professor of Design for Islamic Culture Thesis Supervisor A ccep ted b y ........................................................................................... Roy Strickland Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Department of Architecture JUN 2 0 1997 Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MIT Libraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://Ilibraries.mit.eduldocs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Some pages in the original document contain color / grayscale pictures or graphics that will not scan or reproduce well. Readers: Ali Asani, (John L. Loeb Associe e Professor of the Humanities, Harvard Univer- sity Faculty of Arts and Sciences). Sibel Bozdogan, (Associate Professor of Architecture, MIT). Hasan-ud-din Khan, (Visiting Associate Professor, AKPIA, MIT). -

Page 1 of 15 Page 1 of 15 Netsol Technologies Limited E-Credit of 25

Page 1 of 15 Page 1 of 15 NetSol Technologies Limited E-Credit of 25% Final Cash Dividend (D-6) For the Year Ended 30-06-2018 S.No(s) Warrant # CNIC/NICOP Shareholder Name Participant Id CDC Account Folio Number Bank Name Bank Branch Address International Bank Account Number Net Dividend Amount Address Dividend Status Reason Financial Year Date Of Issue Dividend Pay Date IBAN 1 60000001 35201-4723624-7 SALIM ULLAH GHAURI 1 ASKARI BANK LIMITED ASKARI BANK LIMITED BLOCK-Z, PHASE-III, COMMERCIAL, LAHORE. PK60ASCM0000270100011249 1,143,250.00 U-178, DHA, LAHORE, CANTT. Paid 2017-18 09/11/2018 09/11/2018 With IBAN 2 60000002 n/a NETSOL TECHNOLOGIES INC. 5 84,508,496.00 24025 PARK SORRENTO, SUITE 220 CALABASAS CA, 91302 U.S.A. Paid 2017-18 09/11/2018 09/11/2018 Without IBAN 3 60000003 42301-3653026-7 MR. IRFAN MUSTAFA 7 214,978.50 233- WIL SHINE BULEVARD, SUITE NO.930, SANTA MONIKA, CALIFORNIA 90401. Withheld Without IBAN 2017-18 09/11/2018 Without IBAN 4 60000004 352015-245672-5 NAEEM ULLAH GHAURI 10 MEEZAN BANK LIMITED MEEZAN BANK LIMITED Zahoor Elahi Road Branch, Lahore PK54MEZN0002540101452586 100.00 1 TOWN MEADOW, BRENTFORD, MIDDLESEX TW8 OBQ. ENGLAND. Paid 2017-18 09/11/2018 09/11/2018 With IBAN 5 60000005 35201-1630360-5 NAJEEB ULLAH GHAURI 11 ASKARI BANK LIMITED ASKARI BANK LIMITED BLOCK-Z, PHASE-III, COMMERCIAL, LAHORE PK28ASCM0000270100061780 498,312.00 H NO. 178-U, PHASE -2, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, LAHORE CANTT, DISTRICT LAHORE. Paid 2017-18 09/11/2018 09/11/2018 With IBAN 6 60000006 35201-5861333-9 MR. -

Volume 3, 2021 University of Toronto, Graduate Union of Students of Art History

INTAGLIO Volume 3, 2021 University of Toronto, Graduate Union of Students of Art History Beloved Mosque: The Wazir Khan Masjid of Lahore Sanniah Jabeen The Wazir Khan mosque is located in the Walled City of Lahore, along the southern side of Lahore's Shahi Guzargah, or “Royal Road.” This was the traditional route traversed by Mughal nobles and their guests on their way to royal residences at the Lahore Fort. The mosque is situated approximately 260 meters west of the Delhi Gate, where the mosque's Shahi Hammam (Royal Bath) is also located. The mosque faces both a town square, known as Wazir Khan Chowk, and the Chitta (White) Gate. A trip through the Delhi Gate to the Wazir Khan Chowk is an explosion of the senses. If one searches for images of the Delhi Gate Lahore, most incorrectly show the Gate as a wide-open entrance through which vehicles and people can easily pass. If one actually walks through the Delhi Gate, it is absolute chaos. Cars have to be parked many blocks away and visitors have to push through busy cart vendors, donkeys, hens, the occasional cow, as well as young men carrying twice their body weight in fruit, shoes, eatables, and clothing items. The Walled City of Lahore is the only place in the city where human driven carts still exist, as many streets are almost too narrow to allow motor vehicles or even donkey carts. The call for the prayer bellows periodically from the minarets of the Wazir Khan mosque and an increasing cacophony of human chatter, rickshaws, and motorbikes fills the air. -

Wazir Khan's Mosque

RELIGIOUS TOURISM Wazir Khan’s Mosque An embellishment is manifest! > Writer: M. Zubair Tahir Photos: Faraz Ahmed Located near Delhi gate of the old walled city of Lahore in Pakistan, Masjid Wazir Khan (Wazir Khan’s Mosque) is an exquisite example of Mogul architecture. Compared with other mosques of its class, it is smaller and not so well known, yet Masjid Wazir Khan occupies a unique place in typical Mogul architecture on account of its eye catching and absorbing display of Islamic art, which is not restricted to the interior but is unusually displayed lavishly on the exterior walls as well. asjid” literally means a place for Mprostration and this word stands for mosque, the Muslims’ place of worship. Sajida, an essential posture of prostration in Muslim prayers, is the humblest expression of submission to Allah, the omnipotent. To express this connection between man and his creator, Islamic art, at times seems to serve as a functional language. Minaret IQÉæŸG Internal view »∏NGO ô¶æe Islamic Tourism – Issue 34 – March-April / 2008 For more information, visit our website www.islamictourism.com 60 RELIGIOUS TOURISM A receptive heart cannot escape without being touched and wholly absorbed into the eye catching and intricate designs of Masjid Wazir Khan. These designs contain all the characteristics of typical Islamic art: they are geometrical patterns, symmetrical, and floral and contain hexagonal or octagonal stars and curvilinear intertwined decorations. Made of bricks, the red plastered walls of the mosque bear Persian inscriptions or Arabic calligraphy in fresco of an excellent durability. Powdered stones like lapis lazuli and minerals were used in the fresco. -

Department of Tourism & Northern Studies MAKING LAHORE A

Department of Tourism & Northern Studies MAKING LAHORE A BETTER HERITAGE TOURIST DESTINATION Muhammad Arshad Master thesis in Tourism- November 2015 Abstract In recent past, tourism has become one of the leading industries of the world. Whereas, heritage tourism is one of the fastest growing sectors in tourism industry. The tourist attractions especially heritage attractions play an important role in heritage destination development. Lahore is the cultural hub of Pakistan and home of great Mughal heritage. It is an important heritage tourist destination in Pakistan, because of the quantity and quality of heritage attractions. Despite having a great heritage tourism potential in Lahore the tourism industry has never flourished as it should be, because of various challenges. This Master thesis is aimed to identify the potential heritage attractions of Lahore for marketing of destination. Furthermore, the challenges being faced by heritage tourism in Lahore and on the basis of empirical data and theoretical discussion to suggest some measures to cope with these challenges to make Lahore a better heritage tourist destination. To accomplish the objectives of this thesis, various theoretical perspectives regarding tourist destination development are discussed in this thesis including, destination marketing and distribution, pricing of destination, terrorism effects on destination, image and authenticity of destination. The empirical data is collected and analyze on the basis of these theories. Finally the suggestions are made to make Lahore a better heritage tourist destination. Key words: Heritage tourism, tourist attractions, tourist destination, destination marketing, destination image, terrorism, authenticity, Lahore. 2 | Page Acknowledgement Working with this Master thesis has been very interesting and challenging at a time. -

Graduate Prospectus2014 Institute of Space Technology

Graduate Prospectus2014 Institute of Space Technology we HELP YOU ACHIEVE YOUR AMBITIONS P R O S P E C T U S 2 141 INSTITUTE OF SPACE TECHNOLOGY w w w . i s t . e d u . p k To foster intellectual and economic vitality through teaching, research and outreach in the field of Space Science & Technology with a view to improve quality of life. www.ist.edu.pk 2 141 P R O S P E C T U S INSTITUTE OF SPACE TECHNOLOGY CONTENTS Welcome 03 Location 04 Introduction 08 The Institute 09 Facilities 11 Extra Curricular Activities 11 Academic Programs 15 Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics 20 Local MS Programs 22 Linked Programs with Beihang University 31 Linked Programs with Northwestern Polytechnic University 49 Department of Electrical Engineering 51 Local MS Programs 53 Linked Programs with University of Surrey 55 Department of Materials Science & Engineering 72 Department of Mechanical Engineering 81 Department of Remote Sensing & Geo-information Science 100 w w w . i s t . e d u . p k Department of Space Science 106 ORIC 123 Admissions 125 Fee Structure 127 Academic Regulations 130 Faculty 133 Administration 143 Location Map 145 1 20 P R O S P E C T U S 2 141 INSTITUTE OF SPACE TECHNOLOGY w w w . i s t . e d u . p k 2 141 P R O S P E C T U S INSTITUTE OF SPACE TECHNOLOGY Welcome Message Vice Chancellor The Institute of Space Technology welcomes all the students who aspire to enhance their knowledge and specialize in cutting edge technologies.