Making Heritage in the Walled City of Lahore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

F:\E\HISTORICUS\2020\NO. 2\A Comparative Study of Domes.Pmd

J.P.H.S., Vol. LXVIII, No. 2 69 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF DOMES OF CONTEMPORARY JAMIA MOSQUES AND MUGHUL HISTORICAL MOSQUES OF LAHORE * USMAN MUHAMMAD BUKSH ** UMER MAHBOOB MALIK * Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture, University of Management and Technology, Lahore e-mail: [email protected] ** Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture, Superior University, Lahore A Jamia mosque has been a major landmark in any Muslim settlement since ages and one of the most important institutions of the Muslim world. A dome, with its typical shape, has been a significant architectural element of a mosque from early times. However scientific, technological and industrial developments gave birth to new structural forms and shapes. Thus there are numerous new possibilities for the shape and form in place of a typical dome. It is being observed that the contemporary features and styles of domes of Lahore are different from the historic mosques of the Mughul era in terms of form, construction methodology, structure support system, materials and interior finishes. Thus objective of the current paper is to compare the architectural features and styles of domes in the Mughul historical mosques with those of the contemporary mosques built in newly established housing colonies in the same city. The objective is focus on evaluation of the changes in stylistic features of the new domes and also on the identification of factors responsible for new developments and contemporary trends in the domes of Lahore. In order to assess, a comparative analysis with the domes of Mughul historical mosques and domes of contemporary mosques from different locations of Lahore is done. -

DC Valuation Table (2018-19)

VALUATION TABLE URBAN WAGHA TOWN Residential 2018-19 Commercial 2018-19 # AREA Constructed Constructed Open Plot Open Plot property per property per Per Marla Per Marla sqft sqft ATTOKI AWAN, Bismillah , Al Raheem 1 Garden , Al Ahmed Garden etc (All 275,000 880 375,000 1,430 Residential) BAGHBANPURA (ALL TOWN / 2 375,000 880 700,000 1,430 SOCITIES) BAGRIAN SYEDAN (ALL TOWN / 3 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 SOCITIES) CHAK RAMPURA (Garision Garden, 4 275,000 880 400,000 1,430 Rehmat Town etc) (All Residential) CHAK DHEERA (ALL TOWN / 5 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIETIES) DAROGHAWALA CHOWK TO RING 6 500,000 880 750,000 1,430 ROAD MEHMOOD BOOTI 7 DAVI PURA (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) 275,000 880 350,000 1,430 FATEH JANG SINGH WALA (ALL TOWN 8 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) GOBIND PURA (ALL TOWNS / 9 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIEITIES) HANDU, Al Raheem, Masha Allah, 10 Gulshen Dawood,Al Ahmed Garden (ALL 250,000 880 350,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) JALLO, Al Hafeez, IBL Homes, Palm 11 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 Villas, Aziz Garden etc KHEERA, Aziz Garden, Canal Forts, Al 12 Hafeez Garden, Palm Villas (ALL TOWN 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) KOT DUNI CHAND Al Karim Garden, 13 Malik Nazir G Garden, Ghous Garden 250,000 880 400,000 1,430 (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) KOTLI GHASI Hanif Park, Garision Garden, Gulshen e Haider, Moeez Town & 14 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 New Bilal Gung H Scheme (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Al Wadood Garden (ALL 15 225,000 880 500,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Ring Road Par (ALL TOWN 16 75,000 880 200,000 -

Ghfbooksouthasia.Pdf

1000 BC 500 BC AD 500 AD 1000 AD 1500 AD 2000 TAXILA Pakistan SANCHI India AJANTA CAVES India PATAN DARBAR SQUARE Nepal SIGIRIYA Sri Lanka POLONNARUWA Sri Lanka NAKO TEMPLES India JAISALMER FORT India KONARAK SUN TEMPLE India HAMPI India THATTA Pakistan UCH MONUMENT COMPLEX Pakistan AGRA FORT India SOUTH ASIA INDIA AND THE OTHER COUNTRIES OF SOUTH ASIA — PAKISTAN, SRI LANKA, BANGLADESH, NEPAL, BHUTAN —HAVE WITNESSED SOME OF THE LONGEST CONTINUOUS CIVILIZATIONS ON THE PLANET. BY THE END OF THE FOURTH CENTURY BC, THE FIRST MAJOR CONSOLIDATED CIVILIZA- TION EMERGED IN INDIA LED BY THE MAURYAN EMPIRE WHICH NEARLY ENCOMPASSED THE ENTIRE SUBCONTINENT. LATER KINGDOMS OF CHERAS, CHOLAS AND PANDYAS SAW THE RISE OF THE FIRST URBAN CENTERS. THE GUPTA KINGDOM BEGAN THE RICH DEVELOPMENT OF BUILT HERITAGE AND THE FIRST MAJOR TEMPLES INCLUDING THE SACRED STUPA AT SANCHI AND EARLY TEMPLES AT LADH KHAN. UNTIL COLONIAL TIMES, ROYAL PATRONAGE OF THE HINDU CULTURE CONSTRUCTED HUNDREDS OF MAJOR MONUMENTS INCLUDING THE IMPRESSIVE ELLORA CAVES, THE KONARAK SUN TEMPLE, AND THE MAGNIFICENT CITY AND TEMPLES OF THE GHF-SUPPORTED HAMPI WORLD HERITAGE SITE. PAKISTAN SHARES IN THE RICH HISTORY OF THE REGION WITH A WEALTH OF CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AROUND ISLAM, INCLUDING ADVANCED MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE. GHF’S CONSER- VATION OF ASIF KHAN TOMB OF THE JAHANGIR COMPLEX IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN WILL HELP PRESERVE A STUNNING EXAMPLE OF THE GLORIOUS MOGHUL CIVILIZATION WHICH WAS ONCE CENTERED THERE. IN THE MORE REMOTE AREAS OF THE REGION, BHUTAN, SRI LANKA AND NEPAL EACH DEVELOPED A UNIQUE MONUMENTAL FORM OF WORSHIP FOR HINDUISM. THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECT OF CONSERVATION IS THE PLETHORA OF HERITAGE SITES AND THE LACK OF RESOURCES TO COVER THE COSTS OF CONSERVATION. -

Catholic Students Are Involved in Protecting Mosques in Pakistan

Chain gang: Students ring mosques in Pakistan Catholic group makes strong show of solidarity in defiance of terrorist attacks on shrines and other religious venues Kamran Chaudhry, Lahore, Pakistan, La Croix International , 22 May 2019 Student activist members of the Catholic-led Youth Development Foundation form a human chain around the Masjid Wazir Khan mosque in Lahore. (Photo by Kamran Chaudhry/ucanews.com) After a suicide bomber killed 12 people on May 8 outside a major Sufi shrine in Lahore, capital of the Pakistani province of Punjab, Sikh activist Gurjeet Singh and his friends made a pact to form human chains around local mosques to physically and symbolically ward off religious extremism. "We spend our weekends protecting Muslim worshipers. This shows our solidarity with our brothers and sisters who subscribe to Islam, the majority faith in Pakistan. It also strengthens interfaith harmony in our troubled society," the 26-year-old told ucanews.com, adding the group plans to ring the bombed Data Darbu shrine in June. The Sikh activist, who launched a free ambulance service last year at a government hospital, joined other interfaith activists in locking hands around the city's Jamia Masjid Minhaj-ul- Quran mosque on May 18 to safeguard the 50-odd worshippers inside. For 20 minutes after sunset, they stood on the grounds of the mosque as it hosted a fast- breaking ritual known as iftar . The morning counterpart to this is known as suhoor — a meal taken just before sunrise. Both are practiced daily during the holy fasting month of Ramadan, which this year runs from May 5 to June 4. -

Social Transformation of Pakistan Under Urdu Language

Social Transformations in Contemporary Society, 2021 (9) ISSN 2345-0126 (online) SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION OF PAKISTAN UNDER URDU LANGUAGE Dr. Sohaib Mukhtar Bahria University, Pakistan [email protected] Abstract Urdu is the national language of Pakistan under article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. Urdu language is the first brick upon which whole building of Pakistan is built. In pronunciation both Hindi in India and Urdu in Pakistan are same but in script Indian choose their religious writing style Sanskrit also called Devanagari as Muslims of Pakistan choose Arabic script for writing Urdu language. Urdu language is based on two nation theory which is the basis of the creation of Pakistan. There are two nations in Indian Sub-continent (i) Hindu, and (ii) Muslims therefore Muslims of Indian sub- continent chanted for separate Muslim Land Pakistan in Indian sub-continent thus struggled for achieving separate homeland Pakistan where Muslims can freely practice their religious duties which is not possible in a country where non-Muslims are in majority thus Urdu which is derived from Arabic, Persian, and Turkish declared the national language of Pakistan as official language is still English thus steps are required to be taken at Government level to make Urdu as official language of Pakistan. There are various local languages of Pakistan mainly: Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, Balochi, Kashmiri, Balti and it is fundamental right of all citizens of Pakistan under article 28 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973 to protect, preserve, and promote their local languages and local culture but the national language of Pakistan is Urdu according to article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. -

Untitled (Rest) 2018 Viewed Altogether, the Set of Drawings Watercolor on Paper with Sculpture Reveal Patterns and 11.7 X 8.3 Inches Punctuations in Thought

GUIDE III CONTENTS 1 LBF 2 LB01 6 Sites Lahore Fort Mubarak Haveli & Tehsil Park Shahi Hammam Lahore Museum Alhamra Art Centre Bagh-e-Jinnah Canal 134 Academic Forum Academic Forum artSpeak Youth Forum 158 Acknowledgments IV V LAHORE BIENNALE FOUNDATION ﻻہور بینالے فاؤنڈیشن ایک غیر منافع (The Lahore Biennale Foundation (LBF بخش تنظیم ہے ، جو فنی تجربات کے is a non-profit organization that seeks to لئے اہم سائٹس فراہم کرنے اور فن کی provide critical sites for experimentation ممکنہ صﻻحیت کو سماجی تنقید کے in the visual arts. LBF focuses on the لئے آلہ کار بنانے میں کوشاں ہے۔ many stages of production, display فاؤنڈیشن کی توجہ ِعصر حاضر میں and reception of contemporary بنائے جانے والے فن پاروں کی پروڈکشن ، art in diverse forms. It understands نمائش، اور پذیرائی کی متنوع صورتوں inclusivity, collaboration, and public کی طرف مرکوز ہے۔ اسکا مرکزی نقطہ engagement as being central to its نظر سماجی تبدیلیوں کے ایجنٹ کے vision and is committed to developing طور پر عوامی شمولیت، اشتراک ، اور the potential of art as an agent of social فنی صﻻحیتوں کو فروغ دینا ہے۔ اس .transformation مقصد کے لئے فاؤنڈیشن پاکستان بھر میں فنی منصوبوں کی اعانت کر رہی To this end, the LBF endeavors to support ہے خاص طور پر وہ جو تحقیق اور art projects across Pakistan especially تجربے پر مبنی ہیں۔ those critical practices which are based on research and experimentation. LBF ﻻہور بینالے فاؤنڈیشن نے مقامی طور پر ﻻہور بینالے فاونڈیشن is supported by government bodies, ِحکومت پنجاب، کمشنر آفس ﻻہور، پارکس اور ہارٹی کلچر اتھارٹی، اور والڈ and has developed enduring relations سٹی اتھارٹی کے تعاون سے ایک سے with international partners. -

P20-30 Layout 1

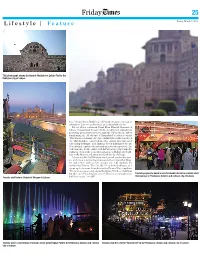

Friday 25 Lifestyle | Feature Friday, March 2, 2018 This photograph shows the historic Mughal-era Lahore Fort in the Pakistani city of Lahore. hore,” claims Ahmer Malik, head of Punjab’s tourism corporation, referring to Lahore’s architectural and cultural attractions. But not all are convinced. Kamil Khan Mumtaz, President of Lahore Conservation Society (LCS), an advocacy organization promoting preservation projects, says the efforts run the risk of transforming the old city into a “Disneyland” to attract tourists. “This was a pedestrian’s city. A pre-Industrial revolution modeled city. This should be conserved into that original state instead of remodeling buildings,” said Mumtaz, who is pushing for the use of traditional construction materials in restoration projects. The calls runs into fresh conflict with infrastructure plans aimed at easing the city’s traffic congestion as Lahore adds high-rise build- ings, malls, flyovers and amusement parks to its cityscape. Lahore was the first Pakistani city to unveil a metro bus serv- ice, and is now constructing an inaugural metro train that Mum- taz and fellow civil society groups say will diminish the architectural history. The city also faces fresh challenges as it opens up to tourism. Canadian visitor Usama Bilal complains: “There are gorgeous old colonial buildings, British era buildings but they are not well taken care of. There is no infrastructure Tourists prepare to board a colorful double decker bus before start their journey in Pakistan’s historic and cultural city of Lahore. Tourists visit historic Badshahi Mosque in Lahore. built for tourists.” — AFP Tourists watch colorful dance fountain at the greater Iqbal Park in the Pakistan’s historic and cultural Tourists visit the colorful “food street” in the Pakistan’s historic and cultural city of Lahore. -

INTEREST FREE LOAN PROGRAMME Plan for Cheque Distribution Ceremonies of Interest Free Loans in the Month of October 2019 Ehsaas Helpline Phone Numbers: Mr

INTEREST FREE LOAN PROGRAMME Plan for Cheque Distribution Ceremonies of Interest free Loans in the Month of October 2019 Ehsaas Helpline Phone Numbers: Mr. Munzir Elahi (Sr. GM, C&M), 0300-5016957, Mr. Farid Sabir (GM, IFL), 0300-5016963, Locations of Cheque distribution Contact Details Date of Sr. No. PO Name Province Districts Ceremony (Loan Center with complete Name of Contact Cell Number Ceremony address) Person Akhuwat Islamic 1 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Jama Masjid Badyara Shreef, Ghari Dupatta Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 22-Oct-19 Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic 2 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Madni Masjid, Dhirkot Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 24-Oct-19 Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic 3 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Jamia Masjid, Harighel Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 23-Oct-19 Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic 4 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Jamia Masjid, Bimber Syed Fahad Abbas 0310-5947365 23-Oct-19 Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic 5 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Jamia Masjid, Barnala Syed Fahad Abbas 0310-5947365 23-Oct-19 Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic 6 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Jamiya Masjid, Chowki Syed Fahad Abbas 0310-5947365 24-Oct-19 Microfinance (AIM) Adnan Anwar, HHRD District Office Hattian, Helping Hand for Relief and 7 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Near Smart Electronics, Choke Bazar, P.O, Adnan Anwer 0341-9488995 15-Oct-19 Development (HHRD) Tehsil & District Hattianbala (Hattian) Adnan Anwar, HHRD District Office Langla, Helping Hand for Relief and 8 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Near Smart Electronics, -

Assessment of the History and Cultural Inclusion of Public Art in Pakistan

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 18 February 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201802.0117.v1 Article Assessment of the History and Cultural Inclusion of Public Art in Pakistan Syed Asifullah Shah1,*, Ashfaq Ahmad Shah 2 and Li Xianfeng 1, 1 Department of Ornamental Horticulture and Landscape Architecture College of Horticulture, China Agricultural University, Beijing, 100193, P.R. China [email protected] [email protected] 2 College of Humanities and Development studies, China Agricultural University, Beijing, 100193, P.R. China [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The significance of arts incorporated with culture inclusion makes the arts a matter of pressing interest. The arts are vital elements of a healthy society that benefits the nations even in difficult social and economic times. Based on the previous studies this research was conducted for the first time in Pakistan to explore the historical background of public art correlated with cultural and religious ethics. Though, Pakistan has a rich cultural history yet the role of modern public art is new and often used unintentionally. Our findings of different surveys conducted in Pakistan including oldest cities such as Lahore, Peshawar and newly developed, the capital city, Islamabad concluded that Public art has a rich cultural and historical background and the local community are enthusiastically connected to it. Different community groups prefer different types of public art in their surroundings depends on the city’s profile, cultural background, and religious mindset of the local community. Overall, the sculptures and depiction of animated beings are not considering right and debatable among the Pakistani societies. -

Old-City Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts

Bāzyāft-31 (Jul-Dec 2017) Urdu Department, Punjab University, Lahore 21 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Amjad Parvez ABSTRACT: Lahore has been known as a crucible of diversified cultures owing to its nature of being a trade center, as well as being situated on the path to the capital city Delhi. Both consumers and invaders, played their part in the acculturation of this city from ancient times to the modern era.This research paperinvestigates the existing as well as the vanishing popular culture of the Old-city Lahore. The cuisine, crafts, kites, music, painting and couture of Lahore advocate the assimilation of varied tastes, patterns and colours, with dissimilar origins, within the narrow streets of the Old- city. This document will cover the food, vendors, artisans, artists and the red-light area, not only according to their locations and existence, butin terms of cultural relations too.The paper also covers the distinct standing of Lahore in the South Asia and its popularity among, not only its inhabitants, but also those who ever visited Lahore. Introduction The Old City of Lahore is characterized by the diversity of cultures that is due tovarious invaders and ruling dynasties over the centuries. The narrow streets, dabbed patches of light andunmatched cuisine add to the colours, fragrance and panorama of this unique place. 22 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Figure 1. “Old-city Lahore Street” (2015) By Amjad Parvez Digital Photograph Personal Collection Inside the Old-city Lahore, one may come the steadiness and stationary quality of time, or even one could feel to have been travelled backward in the two or three centuries when things were hand-made, and the culture was non-metropolitan. -

Archaeology Below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan: the Mughal Underground Chambers

Archaeology below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan: The Mughal Underground Chambers Prepared by Rustam Khan For Global Heritage Fund Preservation Fellowship 2011 Acknowledgements: The author thanks the Director and staff of Lahore Fort for their cooperation in doing this report. Special mention is made of the photographer Amjad Javed who did all the photography for this project and Nazir the draughtsman who prepared the plans of the Underground Chambers. Map showing the location of Lahore Walled City (in red) and the Lahore Fort (in green). Note the Ravi River to the north, following its more recent path 1 Archaeology below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan 1. Background Discussion between the British Period historians like Cunningham, Edward Thomas and C.J Rodgers, regarding the identification of Mahmudpur or Mandahukukur with the present city of Lahore is still in need of authentic and concrete evidence. There is, however, consensus among the majority of the historians that Mahmud of Ghazna and his slave-general ”Ayyaz” founded a new city on the remains of old settlement located some where in the area of present Walled City of Lahore. Excavation in 1959, conducted by the Department of Archaeology of Pakistan inside the Lahore Fort, provided ample proof to support interpretation that the primeval settlement of Lahore was on this mound close to the banks of River Ravi. Apart from the discussion regarding the actual first settlement or number of settlements of Lahore, the only uncontroversial thing is the existence of Lahore Fort on an earliest settlement, from where objects belonging to as early as 4th century AD were recovered during the excavation conducted in Lahore Fort .