Harkishan Lall 1921-2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old-City Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts

Bāzyāft-31 (Jul-Dec 2017) Urdu Department, Punjab University, Lahore 21 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Amjad Parvez ABSTRACT: Lahore has been known as a crucible of diversified cultures owing to its nature of being a trade center, as well as being situated on the path to the capital city Delhi. Both consumers and invaders, played their part in the acculturation of this city from ancient times to the modern era.This research paperinvestigates the existing as well as the vanishing popular culture of the Old-city Lahore. The cuisine, crafts, kites, music, painting and couture of Lahore advocate the assimilation of varied tastes, patterns and colours, with dissimilar origins, within the narrow streets of the Old- city. This document will cover the food, vendors, artisans, artists and the red-light area, not only according to their locations and existence, butin terms of cultural relations too.The paper also covers the distinct standing of Lahore in the South Asia and its popularity among, not only its inhabitants, but also those who ever visited Lahore. Introduction The Old City of Lahore is characterized by the diversity of cultures that is due tovarious invaders and ruling dynasties over the centuries. The narrow streets, dabbed patches of light andunmatched cuisine add to the colours, fragrance and panorama of this unique place. 22 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Figure 1. “Old-city Lahore Street” (2015) By Amjad Parvez Digital Photograph Personal Collection Inside the Old-city Lahore, one may come the steadiness and stationary quality of time, or even one could feel to have been travelled backward in the two or three centuries when things were hand-made, and the culture was non-metropolitan. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

Library Bulletin, November 2017

Volume 6 Issue 11 ISSN: 2309-5032 Volume 6 Issue 10 ISSN: 2309-5032 LIS BULLETIN Library Information Services, CIIT Lahore What is inside? News of the month Journals’ Contents Newspaper’s Clippings And many more Contact Details Serial Section Library Information Services COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Lahore Phone: +92 42 35321094 URL: library.ciitlahore.edu.pk 1 All rights reserves 2017 @ Library Information Services, CIIT Lahore Contents Painting and Calligraphy Exhibition 03 Color, Drawing & Clay Modeling Competitions 05 Games/ Activities during student week, among Library Staff 06 Birthday Celebration and Welcome Party 07 PASTIC Meeting on impact and usage of consortium of S&T and R&D Librarian of Pakistan 08 New Arrival 09 Journals’ Table of contents 12 News Indexing of November 17 News Clippings of November 23 Contact Information 33 2 News of the month Painting and Calligraphy Exhibition Danish Society of Library Information Services, has organized "Painting and Calligraphy Exhibition" on November 7, 2017. Prof Dr. Qaisar Abbas, Director CIIT Lahore and renowned painter and artist, Prof. Dr Ajaz Anwar,Wajid Yaqoot and famous play writer and novelist inaugurated the event. Library In charge Dr. Muhammad Tariq, library staff, members of Danish society and students were present at the inauguration ceremony. The guests visited the paintings and calligraphic paintings and praised the art. In the end, the chief guests distributed the shields to organizers and the members of Danish Society. 3 4 Color, Drawing & Clay Modeling Competitions Library Information Services CIIT-Lahore organized the events of Coloring, Drawing and Clay Modeling during the student week fall 03.11.2017 to 08.11.2017. -

Revival of Punjabi Cinema - Understanding the Dynamics Dr Simran Sidhu Assistant Professor & Head P.G

Global Media Journal-Indian Edition; Volume 12, Issue 2; December 2020.ISSN:2249-5835 Revival of Punjabi cinema - Understanding the dynamics Dr Simran Sidhu Assistant Professor & Head P.G. Dept. of Journalism and Mass Communication Doaba College, Jalandhar Abstract The Punjabi film industry is currently in its growth stage. The Punjabis in the Diasporas gave a new dimension to the Punjabi identity. It has brought a massive boost in the cinema and film music. Pollywood in the North Indian film industry is commercial and art cinema Punjabi is in its initial stage. Producers target just clientele and seldom take the risk. Crisp comedy films overpower an experiment in production, rare themes and different genres. The research did a descriptive analysis with the support of unstructured and semi- structured interviews of producers, actors, and Pollywood directors. The research also explores the need and importance of film institute and film clubs to sensitize the Punjabi audiences regarding the film as a medium, film grammar, and aesthetics. The research also focused on the marketing trends and the vital role of social media in multiplexes' age. Pollywood also lacks in skills and availability of high-end studios for post-production. Indirect taxes and expensive multiplex as a hindrance to attracting rural audiences to remote areas in Punjab. Keywords: Pollywood, Diasporas, multiplex, approach, revival. Introduction Punjab of North India is the most fertile land it also called Sapta Sindhu in 'Vedas'. Agriculture is the main occupation in Punjab. Hard working Punjabis as community adapt to changing condition and adjust a lot faster than others. A considerable amount of literature and Vedas originated in Punjab. -

Anwar Jalal Shemza Cv

ANWAR JALAL SHEMZA CV Born 1928, Simla, India Died 1985, Stafford, UK Education 1956-1960 Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1944-1947 The Mayo School of Art, Lahore, Pakistan Solo Exhibtions 2018 Paintings from the 1960s, Hales Gallery, London, UK 2015 BP Display: Anwar Shemza, Tate Britain, London, UK Drawing, Print, Collage, Jhaveri Contemporary, London, UK 2010 The British Landscape, Green Cardamom, London, UK 2009 Calligraphic Abstraction, Green Cardamom, London, UK 2006 Zahoor-ul-Akhlaq Art Gallery, National College of Arts, Lahore and Pakistan National College of Arts, Rawalpindi, Pakistan 1997 Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, UK 1995 Botanical Gardens Gallery, Birmingham, UK 1992 Manchester Metropolitan University, Alsager, UK 1991 Keele University, Keele, UK 1987 Playhouse Gallery, Canberra, Australia 1985 Roots, Indus Gallery, Karachi, Alhamra Art Centre, Lahore and Pakistan National Council of the Arts Gallery, Islamabad and Peshwar, Pakistan 1972 Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK London, 7 Bethnal Green Road, E1 6LA. T +44 (0)20 7033 1938 New York, 547 West 20th Street, NY 10011. + 1 646 590 0776 www.halesgallery.com @halesgallery 1967 Exhibition of 25 Paintings, Alhamra Art Centre, Lahore and Pakistan National Council of the Arts Gallery, Islamabad and Peshwar, Pakistan 1966 Commonwealth Institute, London, UK 1964 Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK Keele University, Keele, UK Stafford College of Art, Stafford, UK 1963 Paintings, Drawings, 1957-1963, Gulbenkian Museum of Oriental Art and Archaeology, Durham, UK 1962 An -

Theatre & Television Production

FACULTY OF VISUAL ARTS & PERFORMING ARTS Syllabus For MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) (Semester: I – IV) Session: 2019–20 GURU NANAK DEV UNIVERSITY AMRITSAR Note: (i) Copy rights are reserved. Nobody is allowed to print it in any form. Defaulters will be prosecuted. (ii) Subject to change in the syllabi at any time. Please visit the University website time to time. 1 MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) SEMESTER SYSTEM Eligibility: i) Students who have passed B.Voc. (Theatre) from a recognised University or have attained NSQF Level 7 in a particular Industrial Sector in the same Trade OR ii) Bachelor Degree with atleast 50% marks from a recognised University. Semester – I: Courses Hours Marks Paper-I History & Elements of Theatre Theory 3 100 Paper-II Western Drama and Architecture Theory 3 100 Paper-III Punjabi Theatre Theory 3 100 Paper-IV Acting Orientation Practical 3 100 Paper-V Fundamentals of Design Practical 3 100 Semester – II: Courses Hours Marks Paper-I Western Theatre Theory 3 100 Paper-II Fundamentals of Directions Theory 3 100 Paper-III Theatre Production Practical 3 100 Paper-IV Production Management Practical 3 100 Paper-V Stage Craft (Make Up) Practical 3 100 2 MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) SEMESTER SYSTEM Semester – III Courses Hours Marks Paper-I INDIAN THEATRE Theory 3 100 Paper-II MODERN THEATRE & Theory 3 100 INDIAN FOLK THEATRE Paper-III STAGE CRAFT Theory 3 100 Paper-IV PRODUCTION PROJECT Practical 3 100 Paper-V PRODUCTION ANALYSIS Practical 3 100 AND VIVA Semester – IV Courses Hours Marks Paper-I RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Theory 3 100 Paper-II SCREEN ACTING Theory 3 100 Paper-III ACTING Theory 3 100 Paper-IV TELEVISION AND FILM Practical 3 100 APPRECIATION Paper-V FILM PRODUCTION Practical 3 100 3 MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) SEMESTER – I PAPER-I: HISTORY AND ELEMENTS OF THEATRE (Theory) Time: 3 Hours Max. -

Singh, Prof. Rawail

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected] Title Dr. First Name Rawail Last Name Singh Photograph Designation Professor Address G-I, 2nd Floor, South Extn. Part- II, New Delhi - 110049 Phone No Office 27666621 Residence 41314187 Mobile 9212021195 Email [email protected] Web-Page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rawail_Singh Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year M.A. (Punjabi) Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar 1978 Ph.D Punjabi University, Patiala 1999 Career Profile Worked as Assistant Secretary Punjabi academy, Govt, Of NCT of Delhi Worked As Newsreader (Punjabi) in All India Radio Worked as Secretary, Punjabi Academy, Government of NCT of Delhi Joined Delhi University as Professor of Punjabi on 9th May, 2014 Administrative Experience Having vast experience of 35 years in general administration as well as academic administration. Administrative Assignments 1. Nominated as Member, Governing Council (Vice Chancellor’s Nominee), SGND Khalsa College, University of Delhi. 2. Nominated as Member, Governing Council (Vice Chancellor’s Nominee), Mata Sundri College, University of Delhi. 3. Nominated as a member NET Examination Committee By CBSE 4. Nominated as a Expert By UGC For grant of major research projects and Emeritus Fellowship 5. Appointed as Subject expert of language faculty by Punjabi University, Patiala Areas of Interest / Specialization Folk Drama and Dramatic Studies Media Studies and Cinema Analysis Folklore Studies Medieval Literature Subjects Taught Folk Drama and Dramatic Studies Media Studies and Cinema Analysis Folklore Studies Medieval Literature Research Guidance Supervisor of Awarded Doctoral Thesis :- 1. -

Making Heritage in the Walled City of Lahore

Conservation-Led Marginalization: Making Heritage in the Walled City of Lahore Jannat Sohail Urban Studies Supervisor: Maroš Krivý May 25, 2020 Abstract The emerging trajectory of conservation and urban revitalization in the Walled City of Lahore is indicative of its preference for tourism. The shift in the objectives of conservation towards utilizing cultural heritage as a capital resource for negotiating meanings, representations, power, and politics promotes conservation-led marginalization. This is not limited to physical dispossession in the inner- city, but also involuntary social exclusion and the loss of access or restrictions on livelihood opportunities. The pattern of state-sanctioned attempts to render collective ownership of heritage capitalizes on the mediations with national and international institutions to authenticate their decision- making. The role of UNESCO as a status-defined marketing tool in lobbying the local heritage industry, as well as a source of global governance, is understated. The nature and conditions of ‘heritage’ conservation schemas require critical attention, while pivotal questions need to be addressed regarding its rhetorical deployment. The objective of the research is to explore the nature, scope, and effect of the multifaceted national and international institutional framework in the definition, production, consumption, and making of heritage. Keywords: heritage industry, bureaucracy, international agencies, marginalization. 2 Copyright Declaration I hereby declare that: 1. the present Master’s thesis is the result of my personal contribution and it has not been submitted (for defence) earlier by anyone else; 2. all works and important viewpoints by other authors as well as any other data from other sources used in the compilation of the Master’s thesis are duly acknowledged in the references; 3. -

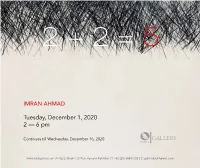

Tuesday, December 1, 2020 2 — 6 Pm

2+2=5 IMRAN AHMAD Tuesday, December 1, 2020 2 — 6 pm Continues till Wednesday, December 16, 2020 www.koelgallery.com | F-42/2, Block 4, Clifton, Karachi, Pakistan | T. +92 (21) 35831292 | E: [email protected] 2+2=5 Reflecting my personality, my bygone experience and my fond memories – my initial fascination with time and space finally combines the varied character traits in my work. Dots, lines, and tones vigorously scratch the metal to construct images from the conscious, the sub-conscious, and the pleasure of mark making with oozing strength and energy leaves me with abstraction narrating long stories with only a stroke. At the same time, a small word illustrated with thousands of lines. This new body of work is based on exploring techniques such as drypoint and Line Etching while depicting my daily life experiences from my surroundings. These images are my feelings, comments, and catharsis while playing truth and dare with the seasons of life. Imran Ahmad From the Series “Nature” Line Etching 3 inch diameter each 2020 From the Series “Nature” Line Etching 3 inch diameter each 2020 From the Series “Nature” Line Etching 3 inch diameter each 2020 From the Series “Nature” Line Etching 3 inch diameter each 2020 From the Series “Nature” Line Etching 3 inch diameter each 2020 From the Series “Nature” Line Etching 3 inch diameter each 2020 From the Series “Nature” Line Etching 3 inch diameter each 2020 From the Series “Nature” Line Etching 3 inch diameter each 2020 From the Series “Nature” Line Etching 3 inch diameter each 2020 From the -

Anwar Jalal Shemza Cv

H A L E s ANWAR JALAL SHEMZA CV Born 1928, Simla, India Died 1985, Stafford, UK Education 1956-1960 Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1944-1947 The Mayo School of Art, Lahore, Pakistan Solo Exhibtions 2019 Anwar Jalal Shemza: Various Works (1961–1969), Sharjah Biennale 14: Making New Time, Sharjah, UAE 2018 Paintings from the 1960s, Hales Gallery, London, UK 2015 BP Display: Anwar Shemza, Tate Britain, London, UK Drawing, Print, Collage, Jhaveri Contemporary, London, UK 2010 The British Landscape, Green Cardamom, London, UK 2009 Calligraphic Abstraction, Green Cardamom, London, UK 2006 Zahoor-ul-Akhlaq Art Gallery, National College of Arts, Lahore and Pakistan National College of Arts, Rawalpindi, Pakistan 1997 Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, UK 1995 Botanical Gardens Gallery, Birmingham, UK 1992 Manchester Metropolitan University, Alsager, UK 1991 Keele University, Keele, UK 1987 Playhouse Gallery, Canberra, Australia London, 7 Bethnal Green Road, El 6LA. + 44 (0)20 7033 1938 New York, 547 West 20th Street, NY 10011. + 1 646 590 0776 www.halesgallery.com f W ~ @halesgallery H A L E s 1985 Roots, Indus Gallery, Karachi, Alhamra Art Centre, Lahore and Pakistan National Council of the Arts Gallery, Islamabad and Peshwar, Pakistan 1972 Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK 1967 Exhibition of 25 Paintings, Alhamra Art Centre, Lahore and Pakistan National Council of the Arts Gallery, Islamabad and Peshwar, Pakistan 1966 Commonwealth Institute, London, UK 1964 Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK Keele University, Keele, UK Stafford College -

Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich Journal of Global Theatre

Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich Journal of Global Theatre History Translocating Theatre History Editors Christopher Balme and Nic Leonhardt Vol. 2, No. 1, 2017 Editorial Office Gwendolin Lehnerer Editorial Board Derek Miller (Harvard), Helen Gilbert (Royal Holloway London) Stanca Scholz-Cionca (Trier/Munich), Kati Röttger (Amsterdam) Marlis Schweitzer (York University, Toronto) Roland Wenzlhuemer (Heidelberg), Gordon Winder (Munich) Published under the Creative Commons License CC-BY 4.0 All rights reserved by the Authors Journal of Global Theatre History Vol. 2, No. 1, 2017 Table of Contents Nic Leonhardt Editorial .......................................................................................................................................III–IV Danijela Weber-Kapusta Travelling Theatre Companies and Transnational Audiences. A Case Study of Croatia in the Nineteenth Century ..........................................................................................................................................1–21 Laurence Senelick Musical Theatre as a Paradigm of Translocation .......................................................................................................................................22–36 Viviana Iacob Caragiale in Calcutta: Romanian-Indian Theatre Diplomacy during the Cold War .......................................................................................................................................37–46 Table of Contents II Journal of Global Theatre History ISSN: 2509-6990 Vol. 2, -

THE TRADE MARKS JOURNAL August, 2010

THE TRADE MARKS JOURNAL (No.715, AUGUST 1, 2010) 512 Regd. No. S. 1395 TMR-01-08-2010 Journal No. 715 THE TRADE MARKS JOURNAL August, 2010 (Registered as a Newspaper) ISSUED UNDER THE DIRECTIONS OF THE REGISTRAR OF TRADE MARKS REGISTRY, KARACHI THE TRADE MARKS JOURNAL (No.715, AUGUST 1, 2010) 513 Regd. No. S. 1395 TMR-01-08-2010 Journal No.715 THE TRADE MARKS JOURNAL (Registered as a Newspaper) st No. 715 August, 1 2010 APPLICATIONS OPPOSITION Applications for registrations of Trade Marks Notice is hereby given that any person in respect of Goods and Services may be made at who has grounds of opposition to the registration of any of the marks advertised IPO-PAKISTAN HEADQUARTERS herein according to classes under the # 23, Street # 87, Sector # G-6/3, heading “Application Advertised before Attaturk Avenue, Embassy Road, Registration” may, within two months from ISLAMABAD the date of this Journal, lodge Notice of Ph: 051-9208146-47 Opposition on Form T.M-5 accompanied by Fax: 051-9208157 the prescribed fee of Rs.6,000/-. TRADE MARKS REGISTRY The period for lodging Notice of Plot No. CD-3, Behind K.D.A. Civic Centre, 3rd, 4th & 5th Floor Defunct CCI & E Building Gulshan-e- Opposition may be extended by the Registrar Iqbal, Karachi. if he thinks so and upon such terms as he Ph: 99230538-99231002-99230533 may direct. Fax: 9231001 BRANCH TRADE MARKS REGISTRY Request for extension of time shall always IPO-REGIONAL OFFICE bear the reference the name of prospective House No.15, Block E-1, opponent and the number of Trade Marks, if Shahrah-e-Imam Hussain (A.S) any, to be made basis of opposition.