Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich Journal of Global Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harkishan Lall 1921-2000

185 In Remembrance In Remembrance Mulk Raj Anand 1905-2004 Mulk – A Dear Friend As I pen this name, Mulk Raj Anand, (Mulk as we called him) a number of images flash across my mind. Was he a man or was he a phenomenon? One thing can be said for certain: he lived his life on his own terms – I wonder why God deprived him of completing his century of life? I had the good fortune of being his personal friend. I cannot remember how it happened but this friendship propelled me into a spate of opportunities to be with him when he met the big and mighty and when he walked to feel the weak and lowly of the society. Whenever he came to Chandigarh, he always found time to turn up in my humble residence, perch himself on his favourite seat in the drawing room, the place of prominence from where he could preside over everybody in the room. Immediately on entering, he would start dilating on the topic he had been ruminating over in his mind, and the knowledge would flow through his vocal chords ceaselessly punctuated with many expletives, and telling everybody how unconcerned they all were about the evils of society and about the lack of positive action on their part. He often asked me, why don’t I write a book on Chandigarh and why don’t I write papers and so on. I did pen a booklet – Chandigarh, a presentation in free verse – and he listened to it with great patience and said ‘we shall publish it via Marg Publications’. -

Offenbach 2019 Wiederentdeckungen Zum 200

AUSGABE NR. 2 2018/19 WWW.BOOSEY.DE SPECIAL OFFENBACH 2019 WIEDERENTDECKUNGEN ZUM 200. GEBURTSTAG 20 JAHRE OFFENBACH EDITION KECK OEK EDITORIAL & INHALT 20 JAHRE OFFENBACH-ENTDECKUNGEN Yes, We Can Can ... Ein Grußwort Jedesmal ein Abenteuer ... so lautet das Motto, unter dem die Stadt und Region Köln von Marc Minkowski von den 200. Geburtstag Jacques Offenbachs mit einer Fülle von Veranstaltungen feiert ( yeswecancan.koeln). Es hätte auch Nun existiert sie zwanzig das Motto sein können, mit dem Boosey & Hawkes 1999 seine Jahre, und zwanzig Jahre monumentale Offenbach Edition, die OEK, in Angriff nahm arbeiten wir regelmäßig unter der Ägide von Jean-Christophe Keck. Aber das Bonmot lag zusammen – zu unserem noch nicht in der Luft. 2019 feiern wir den 20. Geburtstag der größten Vergnügen. Mit Anne or genau zwanzig Jahren starteten wichtigsten zu nennen, die uns unterstützt sion de Paris“ durchgesetzt hat; die Fas- Ausgabe zusammen mit dem 200. unseres Komponisten, und Sofie von Otters Rezital im wir die kritische Ausgabe der Wer- und mit uns zusammengearbeitet haben. sung der Pariser Uraufführung; schließlich wir freuen uns, dass dies in so enger Kooperation nicht nur mit Pariser Châtelet hat alles V ke Jaques Offenbachs mit seiner Auch die Archive der Verlagshäuser haben die überarbeitete Fassung für die Wiener der Stadt Köln, ihren Institutionen, den Organisatorinnen und begonnen. Seither reihen sich ersten abendfüllenden opéra-bouffon Or- oft schöne Funde ermöglicht, insbesonde- Bühnen. Dies sind die drei Eckpfeiler, die Organisatoren geschehen kann, sondern mit einer Fülle von Konzerte und Inszenierungen phée aux Enfers von 1858, unmittelbar ge- re diejenigen von Offenbachs historischen in der Regel den Takt für die Aufarbeitung Theatern, Orchestern und begeisterten Musiker*innen. -

Revival of Punjabi Cinema - Understanding the Dynamics Dr Simran Sidhu Assistant Professor & Head P.G

Global Media Journal-Indian Edition; Volume 12, Issue 2; December 2020.ISSN:2249-5835 Revival of Punjabi cinema - Understanding the dynamics Dr Simran Sidhu Assistant Professor & Head P.G. Dept. of Journalism and Mass Communication Doaba College, Jalandhar Abstract The Punjabi film industry is currently in its growth stage. The Punjabis in the Diasporas gave a new dimension to the Punjabi identity. It has brought a massive boost in the cinema and film music. Pollywood in the North Indian film industry is commercial and art cinema Punjabi is in its initial stage. Producers target just clientele and seldom take the risk. Crisp comedy films overpower an experiment in production, rare themes and different genres. The research did a descriptive analysis with the support of unstructured and semi- structured interviews of producers, actors, and Pollywood directors. The research also explores the need and importance of film institute and film clubs to sensitize the Punjabi audiences regarding the film as a medium, film grammar, and aesthetics. The research also focused on the marketing trends and the vital role of social media in multiplexes' age. Pollywood also lacks in skills and availability of high-end studios for post-production. Indirect taxes and expensive multiplex as a hindrance to attracting rural audiences to remote areas in Punjab. Keywords: Pollywood, Diasporas, multiplex, approach, revival. Introduction Punjab of North India is the most fertile land it also called Sapta Sindhu in 'Vedas'. Agriculture is the main occupation in Punjab. Hard working Punjabis as community adapt to changing condition and adjust a lot faster than others. A considerable amount of literature and Vedas originated in Punjab. -

Schriftenreihe Des Sophie Drinker Instituts Band 4

Schriftenreihe des Sophie Drinker Instituts Herausgegeben von Freia Hoffmann Band 4 Marion Gerards, Freia Hoffmann (Hrsg.) Musik – Frauen – Gender Bücherverzeichnis 1780–2004 BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg 2006 Das Werk ist einschließlich aller seiner Teile urheberrechtlich ge- schützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechts bedarf der Zustimmung der Autorinnen. Dies gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Medien. © BIS-Verlag, Oldenburg 2006 Umschlaggestaltung: Marta Daul Layout und Satz: BIS-Verlag Verlag / Druck / BIS-Verlag Vertrieb: der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Postfach 25 41, 26015 Oldenburg Tel.: 0441/798 2261, Telefax: 0441/798 4040 e-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.bis.uni-oldenburg.de ISBN 3-8142-0966-4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort 3 Hinweise zur Benutzung 5 1 Nachschlagewerke 9 1.1 Lexika und biographische Nachschlagewerke 9 1.2 Bibliographien 14 1.3 Notenverzeichnisse 17 1.4 Diskographien 22 2 Einführende Literatur 24 2.1 Kunstmusik 24 2.2 Populäre Musik (Jazz, Rock, Pop, Volksmusik, Chansons, Weltmusik u. ä.) 42 2.3 Stilübergreifend und Sonstige 50 3 Personenbezogene Darstellungen 54 3.1 Kunstmusik 54 3.2 Populäre Musik (Jazz, Rock, Pop, Volksmusik, Chansons, Weltmusik u. ä.) 320 3.3 Stilübergreifend und Sonstige 433 4 Spezielle Literatur 446 4.1 Kunstmusik 446 4.2 Populäre Musik (Jazz, Rock, Pop, Volksmusik, Chansons, Weltmusik u. ä.) 462 4.3 Stilübergreifend -

(1790 Salzburg — 1862 Wien) Komponist, Hofkapellmei

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Österreichs Museen stellen sich vor Jahr/Year: 1983 Band/Volume: 17 Autor(en)/Author(s): Anonymus Artikel/Article: Musikgräber und -gedenkstätten am Wiener Zentralfriedhof 43-50 © Bundesministerium f. Wissenschaft und Forschung; download unter www.zobodat.at MUSIKERGRÄBER UND -GEDENKSTÄTTEN AM WIENER ZENTRALFRIEDHOF ASSMAYR Ignaz (1790 Salzburg — 1862 Wien) Komponist, Hofkapellmeister, Organist; Schüler Michael Haydns; exhumiert vom Währinger Allgemeinen Friedhof 15 H/2/17 BAYER Josef (1852 Wien — 1913 Wien) Hofkapellmeister der Wiener Hofoper und Ballettkomponist (»Puppenfee«, »Wiener Walzer») 0/66 (links vom Haupttor, Ehrengrab) BEETHOVEN Ludwig van (16. 12. 1770 Bonn — 26. 3. 1827 Wien) kam 1787 nach Wien; exhumiert vom Währinger Ortsfriedhof 32 A/29 (Ehrengrab) BERTE Heinrich (1857 Ungarn — 1924 Perchtoldsdorf) Komponist (»Das Dreimäderlhaus«) 59 A/6/16 BITTNER Julius (1874 Wien — 1939 Wien) Komponist, bekannt durch seine Opern »Das höllisch Gold« und »Die rote Gret« 32 C/15 (Ehrengrab) BÖSENDORFER Ludwig (1835 Wien — 1919 Wien) Klavierfabrikant, Schwiegervater Alexander Girardis 17 B/Gruftreihe BRAHMS Johannes Dr., (7. 5. 1833 Hamburg — 3. 4. 1897 Wien) Komponist, Dirigent der Singakademie, 4 Symphonien, Lieder, Rhapsodien, Ungarische Tänze, Klavierkonzerte, Denkmal am Karlsplatz 32 A/26 (Ehrengrab) BRÜLL Ignaz (1846 Proßnitz, Mähren — 1907 Wien) Pianist und Komponist der Oper »Das goldene Kreuz« 52 A /l (Israelit. Abteilung 1. Tor) DINGELSTEDT Franz Dr. (1814 — 1881, Wien) Dramaturg, Direktor der Hofoper 1867 — 1870 (25. 5. 1869 Eröffnung des neuen Hauses mit »Don Juan«), ab 1870 Direktor des Hofburgtheaters 5 a/40/80 DOSTAL Hermann (1874 — 1930) Komponist und Kapellmeister (»Fliegermarsch«) 79/41/22 43 © Bundesministerium f. -

Theatre & Television Production

FACULTY OF VISUAL ARTS & PERFORMING ARTS Syllabus For MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) (Semester: I – IV) Session: 2019–20 GURU NANAK DEV UNIVERSITY AMRITSAR Note: (i) Copy rights are reserved. Nobody is allowed to print it in any form. Defaulters will be prosecuted. (ii) Subject to change in the syllabi at any time. Please visit the University website time to time. 1 MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) SEMESTER SYSTEM Eligibility: i) Students who have passed B.Voc. (Theatre) from a recognised University or have attained NSQF Level 7 in a particular Industrial Sector in the same Trade OR ii) Bachelor Degree with atleast 50% marks from a recognised University. Semester – I: Courses Hours Marks Paper-I History & Elements of Theatre Theory 3 100 Paper-II Western Drama and Architecture Theory 3 100 Paper-III Punjabi Theatre Theory 3 100 Paper-IV Acting Orientation Practical 3 100 Paper-V Fundamentals of Design Practical 3 100 Semester – II: Courses Hours Marks Paper-I Western Theatre Theory 3 100 Paper-II Fundamentals of Directions Theory 3 100 Paper-III Theatre Production Practical 3 100 Paper-IV Production Management Practical 3 100 Paper-V Stage Craft (Make Up) Practical 3 100 2 MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) SEMESTER SYSTEM Semester – III Courses Hours Marks Paper-I INDIAN THEATRE Theory 3 100 Paper-II MODERN THEATRE & Theory 3 100 INDIAN FOLK THEATRE Paper-III STAGE CRAFT Theory 3 100 Paper-IV PRODUCTION PROJECT Practical 3 100 Paper-V PRODUCTION ANALYSIS Practical 3 100 AND VIVA Semester – IV Courses Hours Marks Paper-I RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Theory 3 100 Paper-II SCREEN ACTING Theory 3 100 Paper-III ACTING Theory 3 100 Paper-IV TELEVISION AND FILM Practical 3 100 APPRECIATION Paper-V FILM PRODUCTION Practical 3 100 3 MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) SEMESTER – I PAPER-I: HISTORY AND ELEMENTS OF THEATRE (Theory) Time: 3 Hours Max. -

Die Fledermaus History

Johann Strauss’ Die Fledermaus HISTORY Premiere April 5, 1874 at the Theater an der Wien, Vienna, with the following cast: Alfred, Hr. Rüdinger; Adele, Esther Charles-Hirsch; Rosalinde, Marie Geistinger; Gabriel von Eisenstein, Jani Szika; Dr. Falke, Ferdinand Lebrecht; Frank, Karl Adolf Friese; Prince Orlofsky, Irma Nittinger. North American Premiere November 21, 1874, in New York at the Stadt Theater Last Performed by Washington National Opera September, 2003 in DAR Constitution Hall, featuring Heinz Fricke conducting and Lotfi Mansouri directing with the following cast: Alfred, Jesús Garcia; Adele, Maki Mori; Rosalinde, June Anderson; Gabriel von Eisenstein, Wolfgang Brendel; Dr. Blind, Robert Baker; Dr. Falke, Peter Edelmann; Frank, John Del Carlo; Prince Orlofsky, Elena Obraztsova; Ida, Tammy Roberts; Frosch, Jason Graae; Solo Dancers, Lisa Gillespie and Harlan Bengel. Johann Strauss’ Operas and Operettas Die Lustigen Weiber von Wien (never produced) Indigo und die Vier Ruber, February 10, 1871; Theater-an-der-Wien Der Karneval in Rom, March 1, 1873; Theater-an-der-Wien Die Fledermaus, April 5, 1874; Theater-an-der-Wien Cagliostro in Wien, February 27, 1875; Theater-an-der-Wien Prinz Methusalem, January 3, 1877; Carl Theater Blinde Kuh, December 18, 1878; Theater-an-der-Wien Das Spitzentuch der Königin, October 1, 1880; Theater-an-der-Wien Der Lustige Krieg, November 25, 1881; Theater-an-der-Wien Eine Nacht in Venedig , October 3, 1883; Freidrich-Wilhalmstrasse Theater, Berlin Der Zigeunerbaron, October 24, 1885; Theater-an-der-Wien Simplizius, December 17, 1887, Theater-an-der-Wien Ritter Pasman, January 10, 1893; Hofoperntheater, Wein Fürstin Ninetta, January 10, 1893; Theater-an-der-Wien Waldmeister, December 4, 1895; Theater-an-der-Wien Washington National Opera www.dc-opera.org 202.295.2400 · 800.US.OPERA . -

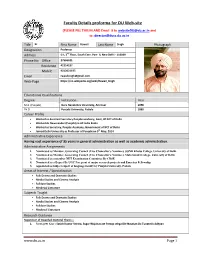

Singh, Prof. Rawail

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected] Title Dr. First Name Rawail Last Name Singh Photograph Designation Professor Address G-I, 2nd Floor, South Extn. Part- II, New Delhi - 110049 Phone No Office 27666621 Residence 41314187 Mobile 9212021195 Email [email protected] Web-Page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rawail_Singh Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year M.A. (Punjabi) Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar 1978 Ph.D Punjabi University, Patiala 1999 Career Profile Worked as Assistant Secretary Punjabi academy, Govt, Of NCT of Delhi Worked As Newsreader (Punjabi) in All India Radio Worked as Secretary, Punjabi Academy, Government of NCT of Delhi Joined Delhi University as Professor of Punjabi on 9th May, 2014 Administrative Experience Having vast experience of 35 years in general administration as well as academic administration. Administrative Assignments 1. Nominated as Member, Governing Council (Vice Chancellor’s Nominee), SGND Khalsa College, University of Delhi. 2. Nominated as Member, Governing Council (Vice Chancellor’s Nominee), Mata Sundri College, University of Delhi. 3. Nominated as a member NET Examination Committee By CBSE 4. Nominated as a Expert By UGC For grant of major research projects and Emeritus Fellowship 5. Appointed as Subject expert of language faculty by Punjabi University, Patiala Areas of Interest / Specialization Folk Drama and Dramatic Studies Media Studies and Cinema Analysis Folklore Studies Medieval Literature Subjects Taught Folk Drama and Dramatic Studies Media Studies and Cinema Analysis Folklore Studies Medieval Literature Research Guidance Supervisor of Awarded Doctoral Thesis :- 1. -

Travelling Theatre Companies and Transnational Audiences. a Case Study of Croatia in the Nineteenth Century

Journal of Global Theatre History ISSN: 2509-6990 Vol. 2, No. 1, 2017, 1–21 Danijela Weber-Kapusta Travelling Theatre Companies and Transnational Audiences. A Case Study of Croatia in the Nineteenth Century Abstract For over a hundred and fifty years, the travelling German theatre companies were some of the most important mediators of the common cultural identity of the Habsburg Monarchy. By tirelessly travelling across the borders of the German-speaking area, they encouraged the emergence of a transnational theatre market in the German language, which extended beyond the borders of the empire, and shaped the theatrical taste of a multi-ethnic audience for decades. This article examines the political and social factors that promoted this transnational distribution of German theatre in the nineteenth century. Particular attention is paid to the linguistic identities of the empire and the model function that Vienna played in shaping the lifestyle and the imagined cultural communities throughout the monarchy. The case study of two Croatian theatre centres – Zagreb and Osijek – examines the role played by the travelling German theatre companies in the spread of the common cultural identity on the one hand and in the development of professional Croatian theatre on the other. Author Danijela Weber-Kapusta studied theatre studies, German language and literature and comparative literature at Zagreb University (Croatia) and obtained her PhD in Theatre Studies from LMU Munich in 2011. She was research associate of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Zagreb (Institute of Theatre History 2005-2007), external research associate of the Institute of Lexicography Miroslav Krleža in Zagreb (2007- 2009), lecturer at the Institute for Theatre Studies at LMU Munich (2009-2011) and external research associate of the Austrian Academy of the Sciences in Vienna (Institute of Cultural Studies and Theatre History 2015-2016). -

Calliope Austria – Women in Society, Culture and the Sciences

CALLIOPE Austria Women in Society, Culture and the Sciences 1 CALLIOPE Austria Women in Society, Culture and the Sciences CALLIOPE Austria Women in Society, Culture and the Sciences Future Fund of the Republic of Austria Sources of inspiration are female – Federal Minister Sebastian Kurz 7 A new support programme for Austrian international cultural work – Teresa Indjein 9 Efforts to create equality worldwide – Ulrike Nguyen 11 An opportunity for effecting change: fundamental research on the issue of women’s rights in Austria 13 biografiA – an encyclopaedia of Austrian women 14 Ariadne – the service centre for information and documentation specific to women’s issues at the Austrian National Library 16 Protagonists for celebration, reflection and forward thinking 1 Creating facts: women and society 23 1.1 Power and powerlessness: women in the Habsburg Monarchy 25 1.2 Women’s rights are human rights: the women’s movement in Austria 31 1.3 Courageous, proactive, conspiratorial: women in the resistance against National Socialism 47 2 Creating free spaces: women and the arts 61 2.1 Women and architecture 63 2.2 Women and the fine arts 71 2.3 Women and design/graphics/applied arts 85 2.4 Women and fashion/Vienna couture 93 2.5 Women and film 99 2.6 Women and photography 111 2.7 Women and literature 121 2.8 Women and music 153 2.9 Women and theatre 163 2.10 Women and dance 173 2.11 Women and networks/salonières 181 Creating spaces for thought and action: 3 women and education 187 3.1 Schooling and higher education by women/for women and girls 189 3.2 Women and the sciences 197 3.2.1 Medicine and psychology 198 3.2.2 Natural sciences 206 3.2.3 Humanities 217 3.2.4 Social, economic and political sciences 223 Notes 234 Directory of the protagonists 254 Overview of commemoration dates and anniversaries 256 Imprint 272 Anja Manfredi Re-enacting Anna Pavlova with Heidrun Neumayer, analogue C-print, 70 x 100 cm, 2009 Sources of inspiration are female Austria is a cultural nation, where women make significant contributions to cultural and socio-political life. -

La Gran Duquesa De Gerolstein Jacques Offenbach

1 La gran duquesa de Gerolstein Jacques Offenbach TEMPORADA 2014 - 2015 2 3 echas y horarios Días 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27 y 28 de marzo de 2015 19:00 horas (domingos a las 18:00 horas) F Funciones de abono: 13, 15, 18, 20, 21, 22 y 24 de marzo Duración aproximada: Primer acto: 45 minutos Descanso de 20 minutos Teatro de la Zarzuela Segundo acto: 45 minutos Jovellanos, 4 - 28014 Madrid, España Descanso de 20 minutos Tel. centralita: 34 91 524 54 00 Tercer acto: 40 minutos http://teatrodelazarzuela.mcu.es Departamento de abonos y taquillas: La función del jueves 20 de marzo de 2015 será Tel. 34 915 245 472 y 910 505 282 retransmitida en directo por Radio Clásica (Radio Nacional de España). El Teatro de la Zarzuela es miembro de: El Teatro agradece la colaboración de: Edición del programa: Departamento de comunicación y publicaciones Coordinación editorial y de textos: Víctor Pagán Traducciones: Victoria Stapells Diseño gráfico y maquetación: Bernardo Rivavelarde Impresión: Imprenta Nacional del Boletín Oficial del Estado D.L: M-6456-2015 Nipo: 035-15-027-3 4 5 ZARZUELA BUFA EN TRES ACTOS Y CUATRO CUADROS DE HENRI MEILHAC Y LUDOVIC HALÉVY MÚSICA DE JACQUES OFFENBACH Edición crítica de Jean-Christophe Keck y traducción de Enrique Mejías García (Bossey & Hawkes / Bote & Bock GmbH) Estrenada en el Teatro del Circo (Bufos Arderíus) de Madrid, el 7 de noviembre de 1868 Primera representación en castellano de esta edición Producción del Festival del Valle d’Itria de Martina Franca (1996) Taller de Félix Nadar. -

Offenbach 2019 Wiederentdeckungen Zum 200

AUSGABE NR. 2 2018/19 WWW.BOOSEY.DE SPECIAL OFFENBACH 2019 WIEDERENTDECKUNGEN ZUM 200. GEBURTSTAG 20 JAHRE OFFENBACH EDITION KECK OEK EDITORIAL & INHALT 20 JAHRE OFFENBACH-ENTDECKUNGEN YES, WE CANCAN ... Ein Grußwort ... so lautet das Motto, unter dem die Stadt und Region Köln von Marc Minkowski Jedesmal ein Abenteuer nächstes Jahr den 200. Geburtstag Jacques Offenbachs mit von einer Fülle von Veranstaltungen feiert ( yeswecancan.koeln). Es hätte auch das Motto sein können, mit dem der Verlag Boosey Nun existiert sie zwanzig Jahre, und & Hawkes 1999 seine monumentale Offenbach Edition, die OEK, zwanzig Jahre arbeiten wir regelmä- in Angriff nahm unter der Ägide des Offenbach-Spezialisten Jean- ßig zusammen – zu unserem größten Christophe Keck. Aber das Bonmot lag noch nicht in der Luft. Vergnügen. Mit Anne Sofie von Otters 2019 feiern wir den 20. Geburtstag der Ausgabe zusammen mit Rezital im Pariser Châtelet hat alles or genau zwanzig Jahren starteten wichtigsten zu nennen, die uns unterstützt sion de Paris“ durchgesetzt hat; die Fas- dem 200. unseres Komponisten, und wir freuen uns, dass dies begonnen. Seither reihen sich Konzerte wir die kritische Ausgabe der Wer- und mit uns zusammengearbeitet haben. sung der Pariser Uraufführung; schließlich in so enger Kooperation mit der Stadt Köln, ihren Institutionen, und Inszenierungen aneinander: La V ke Jaques Offenbachs mit seiner Auch die Archive der Verlagshäuser haben die überarbeitete Fassung für die Wiener den Organisatorinnen und Organisatoren geschehen kann. Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein, Les ersten abendfüllenden opéra-bouffon Or- oft schöne Funde ermöglicht, insbesonde- Bühnen. Dies sind die drei Eckpfeiler, die Fées du Rhin, Les Contes d’Hoffmann, phée aux Enfers von 1858, unmittelbar ge- re diejenigen von Offenbachs historischen in der Regel den Takt für die Aufarbeitung „Ansichten (k)eines Clowns“ – so könnte, in Anlehnung an das Concerto militaire, La Périchole ..