Performing Masculinity in Johann Strauss's Die

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2018 This

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2018 This is the fifteenth year that MusicWeb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2017-November 2018). The 130 selections have come from 25 members of the team and 70 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources - I say that every year, but still the spread of choices surprises and pleases me. Of the selections, 8 have received two nominations: Mahler and Strauss with Sergiu Celibidache on the Munich Phil choral music by Pavel Chesnokov on Reference Recordings Shostakovich symphonies with Andris Nelsons on DG The Gluepot Connection from the Londinium Choir on Somm The John Adams Edition on the Berlin Phil’s own label Historic recordings of Carlo Zecchi on APR Pärt symphonies on ECM works for two pianos by Stravinsky on Hyperion Chandos was this year’s leading label with 11 nominations, significantly more than any other label. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2400 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year, but this year the choice was a little easier than usual. Pavel CHESNOKOV Teach Me Thy Statutes - PaTRAM Institute Male Choir/Vladimir Gorbik rec. 2016 REFERENCE RECORDINGS FR-727 SACD The most significant anniversary of 2018 was that of the centenary of the death of Claude Debussy, and while there were fine recordings of his music, none stood as deserving of this accolade as much as the choral works of Pavel Chesnokov. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

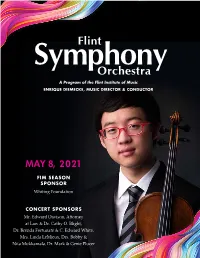

Flint Orchestra

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

Western Performing Arts in the Late Ottoman Empire: Accommodation and Formation

2020 © Özgecan Karadağlı, Context 46 (2020): 17–33. Western Performing Arts in the Late Ottoman Empire: Accommodation and Formation Özgecan Karadağlı While books such as Larry Wolff’s The Singing Turk: Ottoman Power and Operatic Emotions on the European Stage offer an understanding of the musicological role of Ottoman-Turks in eighteenth-century European operatic traditions and popular culture,1 the musical influence and significance going the other way is often overlooked, minimised, and misunderstood. In the nineteenth century, Ottoman sultans were establishing theatres in their palaces, cities were hosting theatres and opera houses, and an Ottoman was writing the first Ottoman opera (1874). This article will examine this gap in the history of Western music, including opera, in the Ottoman period, and the slow amalgamation of Western and Ottoman musical elements that arose during the Ottoman Empire. This will enable the reader to gauge the developments that eventually marked the break between the Ottoman era and early twentieth-century modern Turkey. Because even the words ‘Ottoman Empire’ are enough to create a typical orientalist image, it is important to build a cultural context and address critical blind spots. It is an oft- repeated misunderstanding that Western music was introduced into modern-day Turkey after 1 Larry Wolff, The Singing Turk: Ottoman Power and Operatic Emotions on the European Stage (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016). 17 18 Context 46 (2020): Karadağlı the proclamation of the Republic in 1923.2 As this article will demonstrate, the intercultural interaction gave rise to institutional support, and as Western music became a popular and accepted genre in the Ottoman Empire of the nineteenth century,3 it influenced political and creative aspirations through the generation of new nationalist music for the Turkish Republic.4 Intercultural Interaction: Pre-Tanzimat and İstibdat Periods, 1828–1908 Although Western music arrived in the Empire in the sixteenth century,5 it took almost two and a half centuries to become established. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Johann Strauss: "Die Fledermaus"

JOHANN STRAUSS DIE FLEDERMAUS Operette in drei Aufzügen Eine Veranstaltung des Departments für Musiktheater in Kooperation mit den Departments für Gesang, Bühnenbild- und Kostümgestaltung, Film- und Ausstellungsarchitektur sowie Schauspiel/Regie – Thomas Bernhard Institut Mittwoch, 2. Dezember 2015 Donnerstag, 3. Dezember 2015 Freitag, 4. Dezember 2015 19.00 Uhr Samstag, 5. Dezember 2015 17.00 Uhr Großes Studio Universität Mozarteum Mirabellplatz 1 Besetzung 2.12. / 4.12. 3.12. / 5.12. Musikalische Leitung Kai Röhrig Szenische Leitung Karoline Gruber Gabriel von Eisenstein, Notar Markus Ennsthaller Michael Etzel Bachelor Gesang, 3. Semester Bachelor Gesang, 7. Semester Bühne Anna Brandstätter / Christina Pointner Kostüme Iris Jedamski Rosalinde, seine Frau Sassaya Chavalit Julia Rath Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Regieassistenz Agnieszka Lis Orlofsky Alice Hoffmann Reba Evans Dramaturgie Ronny Dietrich Master Gesang, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 1. Semester Dialogarbeit Ulrike Arp Dr. Falke, Notar Thomas Hansen Darian Worrell Licht Christina Pointner / Anna Ramsauer Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 1. Semester Musikalische Einstudierung Lenka Hebr, Dariusz Burnecki, Andrea Strobl Alfred, Gesangslehrer Thomas Huber Jungyun Kim Musikalische Assistenz Wolfgang Niessner Master Gesang, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Technische Leitung Andreas Greiml, Thomas Hofmüller Frank, Gefängnisdirektor Felix Mischitz Felix Mischitz Bühnen-, Beleuchtungs-, Michael Becke, Sebastian Brandstätter, Markus Ertl, Bachelor Gesang, 5. Semester Bachelor Gesang, 5. Semester Tontechnik und Werkstätten Rafael Fellner, Sybille Götz, Markus Graf, Peter Hawlik, Alexander Lährm, Anna Ramsauer, Elena Wagner Adele, Kammermädchen Jennie Lomm Claire Austin Salonorchester der Universität Mozarteum Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Violine 1 Kamille Kubiliute Ida, ihre Schwester Domenica Radlmaier Sarah Bröter Violine 2 Elia Antunez Bachelor Gesang, 9. -

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 1 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch, 1870 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 2 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch (1838–1920) Complete Symphonies CD 1 Symphony No. 1 op. 28 in E flat major 38'04 1 Allegro maestoso 10'32 2 Intermezzo. Andante con moto 7'13 3 Scherzo. Presto 5'00 4 Quasi Fantasia. Grave 7'30 5 Finale. Allegro guerriero 7'49 Symphony No. 2 op. 36 in F minor 39'22 6 Allegro passionato, ma un poco maestoso 15'02 7 Adagio ma non troppo 13'32 8 Allegro molto tranquillo 10'57 T.T.: 77'30 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 3 13.03.2020 10:56:27 CD 2 1 Prelude from Hermione op. 40 8'54 (Concert ending by Wolfgang Jacob) 2 Funeral march from Hermione op. 40 6'15 3 Entr’acte from Hermione op. 40 2'35 4 Overture from Loreley op. 16 4'53 5 Prelude from Odysseus op. 41 9'54 Symphony No. 3 op. 51 in E major 38'30 6 Andante sostenuto 13'04 7 Adagio ma non troppo 12'08 8 Scherzo 6'43 9 Finale 6'35 T.T.: 71'34 Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino, Conductor cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 4 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Bamberger Symphoniker (© Andreas Herzau) cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 5 13.03.2020 10:56:28 Auf Eselsbrücken nach Damaskus – oder: darüber, daß wir es bei dieser Krone der Schöpfung Der steinige Weg zu Bruch dem Symphoniker mit einem Kompositum zu tun haben, das sich als Geist mit mehr oder minder vorhandenem Verstand in einem In der dichtung – wie in aller kunst-betätigung – ist jeder Körper darstellt (die Bezeichnungen der Ingredienzien der noch von der sucht ergriffen ist etwas ›sagen‹ etwas ›wir- mögen wechseln, die Tatsache bleibt). -

Early 20Th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: a Cosmopolitan Genre

This is a repository copy of Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/150913/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Scott, DB orcid.org/0000-0002-5367-6579 (2016) Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre. The Musical Quarterly, 99 (2). pp. 254-279. ISSN 0027-4631 https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdw009 © The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press. This is an author produced version of a paper published in The Musical Quarterly. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre Derek B. Scott In the first four decades of the twentieth century, new operettas from the German stage enjoyed great success with audiences not only in cities in Europe and North America but elsewhere around the world.1 The transfer of operetta and musical theatre across countries and continents may be viewed as cosmopolitanism in action. -

Boogiewoogie.Ru Boogiewoogie.Ru Boogiewoogie.Ru Boogiewoogie.Ru

BOOGIEWOOGIE.RU BOOGIEWOOGIE.RU BOOGIEWOOGIE.RU BOOGIEWOOGIE.RU Contents ALL THE I-IVELONG DAY (And The Long, Long Night), 141 THE BACK BAY POLKA, 119 BESS YOU IS MY WOMAN, 9 (I've Got) BEGINNER'S LUCK, 66 BY STRAUSS, 131 A FOGGY DAY, 87 FOR YOU, FOR ME, FOR EVERMORE, 123 I CAN'T BE BOTHERED NOW, 91 I GOT PLENTY 0' NUTTIN', 17 I LOVE TO RHYME, 103 I WAS DOING ALL RIGHT, 107 IT AIIV'T NECESSARILY SO, 23 THE JOLLY TAR AND THE MILK MAID, 95 JUST ANOTHER RHUMBA, 53 LET'S CALL THE WHOLE THING OFF, 70 LOVE IS HERE TO STAY, 11 1 LOVE WALKED IN, 11 5 MY MAN'S GONE NOW, 29 NICE WORK IF YOU CAN GET IT, 99 OH BESS, OH WHERE'S MY BESS, 35 PROMENADE (Piano Solo), 74 THE REAL AMERICAN FOLK SONG (Is A Rag), 4 SHALL WE DANCE, 78 SLAP THAT BASS, 61 SOPHIA, 136 SUMMERTIME, 40 THERE'S A BOAT DAT'S LEAVIN' SOON FOR NEW YORK, 44 THEY ALL LAUGHED, 82 THEY CAN'T TAKE THAT AWAY FROM ME, 127 A WOMAN IS A SOMETIME THING, 48 For all works contained herein: International Copyright Secured ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Printed in U.S.A. Unauthorized copying, arranging, adapting, recording or public performance is an infringement of copyright. Infringers are liable under the law. THE REAL AMERICAN FOLK BOOGIEWOOGIE.RUSONG (Is A Ras)* Lyrics by IRA GERSHWN Music by GEORGE GERSH WIN 1 " Near Bar - ce - io - na the Deas - int cioons The old tra - di - tion - a1 I You may dis - like, or you 'may a - dore, The na - tire songs from a A Fm6 C Cmaj7 Am7 C dim Span - ish tunes; The Ne - a - pol - i - tan Street Song sighs, You for - eign shore; They may be songs that you can't for - get,- They I I Written for "Ladies First" (1918) The first George and In Gershwin collaboration used in a Broadway show Copyright @ 1959 by Gershwin Publishing Corporation Assigned to Chappell & Co., Inc. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

The War to End War — the Great War

GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE GIVING WAR A CHANCE, THE NEXT PHASE: THE WAR TO END WAR — THE GREAT WAR “They fight and fight and fight; they are fighting now, they fought before, and they’ll fight in the future.... So you see, you can say anything about world history.... Except one thing, that is. It cannot be said that world history is reasonable.” — Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoevski NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND “Fiddle-dee-dee, war, war, war, I get so bored I could scream!” —Scarlet O’Hara “Killing to end war, that’s like fucking to restore virginity.” — Vietnam-era protest poster HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1851 October 2, Thursday: Ferdinand Foch, believed to be the leader responsible for the Allies winning World War I, was born. October 2, Thursday: PM. Some of the white Pines on Fair Haven Hill have just reached the acme of their fall;–others have almost entirely shed their leaves, and they are scattered over the ground and the walls. The same is the state of the Pitch pines. At the Cliffs I find the wasps prolonging their short lives on the sunny rocks just as they endeavored to do at my house in the woods. It is a little hazy as I look into the west today. The shrub oaks on the terraced plain are now almost uniformly of a deep red. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1914 World War I broke out in the Balkans, pitting Britain, France, Italy, Russia, Serbia, the USA, and Japan against Austria, Germany, and Turkey, because Serbians had killed the heir to the Austrian throne in Bosnia.