Assessment of the History and Cultural Inclusion of Public Art in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Symbols of Pakistan | Pakistan General Knowledge

National Symbols of Pakistan | Pakistan General Knowledge Nation’s Motto of Pakistan The scroll supporting the shield contains Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s motto in Urdu, which reads as “Iman, Ittehad, Nazm” translated as “Faith, Unity, Discipline” and are intended as the guiding principles for Pakistan. Official Map of Pakistan Official Map of Pakistan is that which was prepared by Mahmood Alam Suhrawardy National Symbol of Pakistan Star and crescent is a National symbol. The star and crescent symbol was the emblem of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, and gradually became associated with Islam in late 19th-century Orientalism. National Epic of Pakistan The Hamza Nama or Dastan-e-Amir Hamza narrates the legendary exploits of Amir Hamza, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, though most of the stories are extremely fanciful, “a continuous series of romantic interludes, threatening events, narrow escapes, and violent acts National Calendar of Pakistan Fasli which means (harvest) is derived from the Arabic term for division, which in India was applied to the groupings of the seasons. Fasli Calendar is a chronological system introduced by the Mughal emperor Akbar basically for land revenue and records purposes in northern India. Fasli year means period of 12 months from July to Downloaded from www.csstimes.pk | 1 National Symbols of Pakistan | Pakistan General Knowledge June. National Reptile of Pakistan The mugger crocodile also called the Indian, Indus, Persian, Sindhu, marsh crocodile or simply mugger, is found throughout the Indian subcontinent and the surrounding countries, like Pakistan where the Indus crocodile is the national reptile of Pakistan National Mammal of Pakistan The Indus river dolphin is a subspecies of freshwater river dolphin found in the Indus river (and its Beas and Sutlej tributaries) of India and Pakistan. -

Social Transformation of Pakistan Under Urdu Language

Social Transformations in Contemporary Society, 2021 (9) ISSN 2345-0126 (online) SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION OF PAKISTAN UNDER URDU LANGUAGE Dr. Sohaib Mukhtar Bahria University, Pakistan [email protected] Abstract Urdu is the national language of Pakistan under article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. Urdu language is the first brick upon which whole building of Pakistan is built. In pronunciation both Hindi in India and Urdu in Pakistan are same but in script Indian choose their religious writing style Sanskrit also called Devanagari as Muslims of Pakistan choose Arabic script for writing Urdu language. Urdu language is based on two nation theory which is the basis of the creation of Pakistan. There are two nations in Indian Sub-continent (i) Hindu, and (ii) Muslims therefore Muslims of Indian sub- continent chanted for separate Muslim Land Pakistan in Indian sub-continent thus struggled for achieving separate homeland Pakistan where Muslims can freely practice their religious duties which is not possible in a country where non-Muslims are in majority thus Urdu which is derived from Arabic, Persian, and Turkish declared the national language of Pakistan as official language is still English thus steps are required to be taken at Government level to make Urdu as official language of Pakistan. There are various local languages of Pakistan mainly: Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, Balochi, Kashmiri, Balti and it is fundamental right of all citizens of Pakistan under article 28 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973 to protect, preserve, and promote their local languages and local culture but the national language of Pakistan is Urdu according to article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. -

ABSTRACTS Conference on the Music of South, Central and West Asia Harvard University, March 4-6, 2016

ABSTRACTS Conference on the Music of South, Central and West Asia Harvard University, March 4-6, 2016 Margarethe Adams, SUNY Stony Brook In a State of Belief: Korean Church Performance in Kazakhstan The postsecular may be less a new phase of cultural development than it is a working through of the problems and contradictions in the secularization process itself (Dunn 2010:92). Critical theorist, Allen Dunn describes the skepticism of the enlightenment and the disenchantment of modern society as inherently negative. But for those who lived during the Soviet era, the negative aspects of secularization (the closing of mosques, synagogues, and churches; the persecution of religious leaders, and more) were accompanied by a powerfully optimistic ideology with a strong social message promising widespread social change. The Soviet State may not have swept all its citizens along in its optimism, but its departure, after seventy years, left a palpable ideological void. This paper will examine one of the many imported religious institutions that flooded into Central Asia after the fall of the Soviet Union Korean evangelical worship. In this study, based on ethnographic research conducted between 2004 and 2015, I examine Korean church-going practices over the past decade in Almaty, Kazakhstan, particularly focusing on dance, gesture, and musical performance during worship and in holiday celebrations. I seek to clarify how transnational networks are implicated in religious institutions in postsecular Central Asia. Transnationalist discourse figures prominently in interviews with congregation members, both in discussion of family ties to Korea, and in the ways they link the aesthetic choices of gesture to imported styles of worship. -

P20-30 Layout 1

Friday 25 Lifestyle | Feature Friday, March 2, 2018 This photograph shows the historic Mughal-era Lahore Fort in the Pakistani city of Lahore. hore,” claims Ahmer Malik, head of Punjab’s tourism corporation, referring to Lahore’s architectural and cultural attractions. But not all are convinced. Kamil Khan Mumtaz, President of Lahore Conservation Society (LCS), an advocacy organization promoting preservation projects, says the efforts run the risk of transforming the old city into a “Disneyland” to attract tourists. “This was a pedestrian’s city. A pre-Industrial revolution modeled city. This should be conserved into that original state instead of remodeling buildings,” said Mumtaz, who is pushing for the use of traditional construction materials in restoration projects. The calls runs into fresh conflict with infrastructure plans aimed at easing the city’s traffic congestion as Lahore adds high-rise build- ings, malls, flyovers and amusement parks to its cityscape. Lahore was the first Pakistani city to unveil a metro bus serv- ice, and is now constructing an inaugural metro train that Mum- taz and fellow civil society groups say will diminish the architectural history. The city also faces fresh challenges as it opens up to tourism. Canadian visitor Usama Bilal complains: “There are gorgeous old colonial buildings, British era buildings but they are not well taken care of. There is no infrastructure Tourists prepare to board a colorful double decker bus before start their journey in Pakistan’s historic and cultural city of Lahore. Tourists visit historic Badshahi Mosque in Lahore. built for tourists.” — AFP Tourists watch colorful dance fountain at the greater Iqbal Park in the Pakistan’s historic and cultural Tourists visit the colorful “food street” in the Pakistan’s historic and cultural city of Lahore. -

History, Narrative, and the Female Figure (As Disruption) / Rizvi 35 Guises Himself in Jayida’S Clothes to Deceive Her Husband

Shahzia Sikander began studying painting at the National of great artists. Like poetry, paintings were incorporated College of Arts in Lahore, working closely with Bashir into the performative rituals of the court, where the Ahmad, a master of the art of manuscript illustration. The cognoscenti gathered to admire and evaluate the works History, Narrative, “miniature,” as the genre he taught is sometimes referred of art. to, places Sikander’s work in a lineage that is at once Lahore was well known in the sixteenth and sev- local and historically grounded. Although once perceived enteenth centuries as one of the capitals of the Mughal and the by Euro-American scholars as conventional and repeti- Empire, with a magnificent fort, mosques, and gardens. tive, early modern illustrated manuscripts and drawings— The imperial household included talented scribes, poets, the foundation of Sikander’s practice—are now under- and artists from across India. Among the most well Female Figure stood to be a platform for innovation and artistic virtuos- known were Miskin (active ca. 1580–1604) and Basawan ity. Her paintings are in fact imbedded within a complex (active ca. 1580–1600), both of whom were extolled by tradition of art-making, with its strategies of allegory, narration, and appropriation. They build on past prece- dents and are made contemporary through their subject matter and through her rendition, scaled up or down and translated to other media, such as animation. Sikander’s perspective is informed by the social, political, and reli- gious cultures of her home in Lahore, while reflecting her participation in the broader art world of New York, her current residence. -

Second Lahore Biennale: Between the Sun and the Moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists

For Immediate Release 6 January 2020 Second Lahore Biennale: between the sun and the moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists Installed Across Cultural and Heritage Sites Throughout Lahore, Pakistan, from 26 January to 29 February 2020 Lahore, Pakistan—6 January 2020—The Lahore Biennale Foundation today revealed a list of over 70 participating artists for the second edition of the Lahore Biennale (LB02), running from 26 January through 29 February 2020. Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, Director of the Sharjah Art Foundation in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, LB02: between the sun and the moon brings a plethora of artistic projects to cultural and heritage sites throughout the city of Lahore including more than 20 new commissions by artists from across the region and around the world, including Alia Farid, Diana Al-Hadid, Hassan Hajjaj, Haroon Mirza, Hajra Waheed and Simone Fattal, among many others. Other participating artists include Anwar Saeed, Rasheed Araeen and the late Madiha Aijaz. With a focus on the Global South, where ongoing social disaffection is being aggravated by climate change, LB02 responds to the cultural and ecological history of Lahore and aims to awaken awareness of humanity’s daunting contemporary predicament. Works presented in LB02 will explore human entanglement with the environment while revisiting traditional understandings of the self and their cosmological underpinnings. Inspiration for this thematic focus is drawn from intellectual and cultural exchange between South and West Asia. “For centuries, inhabitants of these regions oriented themselves with reference to the sun, the moon, and the constellations. -

Historical Places of Pakistan Minar-E-Pakistan

Historical places of Pakistan Minar-e-Pakistan: • Minar-e-Pakistan (or Yadgaar-e-Pakistan ) is a tall minaret in Iqbal Park Lahore, built in commemoration of the Lahore Resolution. • The minaret reflects a blend of Mughal and modern architecture, and is constructed on the site where on March 23, 1940, seven years before the formation of Pakistan, the Muslim League passed the Lahore Resolution (Qarardad-e-Lahore ), demanding the creation of Pakistan. • The large public space around the monument is commonly used for political and public meetings, whereas Iqbal Park area is ever so popular among kite- flyers. • The tower rises about 60 meters on the base, thus the total height of minaret is about 62 meters above the ground. • The unfolding petals of the flower-like base are 9 meters high. The diameter of the tower is about 97.5 meters (320 feet). Badshahi Mosque: or the 'Emperor's Mosque', was ,( د ه :The Badshahi Mosque (Urdu • built in 1673 by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in Lahore, Pakistan. • It is one of the city's best known landmarks, and a major tourist attraction epitomising the beauty and grandeur of the Mughal era. • Capable of accommodating over 55,000 worshipers. • It is the second largest mosque in Pakistan, after the Faisal Mosque in Islamabad. • The architecture and design of the Badshahi Masjid is closely related to the Jama Masjid in Delhi, India, which was built in 1648 by Aurangzeb's father and predecessor, Emperor Shah Jahan. • The Imam-e-Kaaba (Sheikh Abdur-Rahman Al-Sudais of Saudi Arabia) has also led prayers in this mosque in 2007. -

Guide to Islamabad

GUIDE TO ISLAMABAD Abstract We at the World Bank Group Family Network (WBGFN) Islamabad have put together this short guide to help you with all the basic needs. If you need any more help, feel free to contact the author or any of the other members listed in this guide. WBGFN Islamabad Pakistan Table of Contents WBGFN Islamabad Contacts ................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Climate .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Language .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Time Zone ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Currency ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 Living ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 Childcare and Household Staff ........................................................................................................................ -

Pakistan Business Practices

Islamic Republic of Pakistan Business Practices Ali Hassan Shahid Ali CONTENTS ➢ Overview of Pakistan ➢ History ➢ Geography ➢ People & society ➢ Government ➢ Economy ➢ Business practices Overview of Pakistan ▪ Official Name: ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN ▪ Capital City: ISLAMABAD ▪ Province: 6 ▪ Population: 217,398,737 ▪ Area: 513,120 km2 ▪ Official Language: URDU ▪ Currency: Pak Rupee (PKR) History ➢ The history of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan began on 14 August 1947. ➢ Pakistan government's official chronology started with the Islamic rule over Indian subcontinent by Muhammad bin Qasim which reached its zenith during Mughal Era. ➢ In 1947 Pakistan consisted of West Pakistan (today's Pakistan) and East Pakistan (today's Bangladesh). ➢ The constitution of 1956 made Pakistan an Islamic democratic country. ➢ Pakistan faced a civil war and Indian military intervention in 1971 resulting in the secession of East Pakistan as the new country of Bangladesh. ➢ Pakistan is a nuclear power as well as a declared nuclear-weapon state, having conducted six nuclear tests in response to five nuclear tests of their rival Republic of India in May 1998. ➢ Terrorism due to War of Afghanistan damaged the country's economy and infrastructure to a great extent from 2001-09 but Pakistan is once again developing. ➢ Many economists and think tanks suggested that until 2030 Pakistan become Asian Tiger and CPEC will play an important role in it. Geography Pakistan is a South Asian country shared It’s borders with 4 countries: India, China, Iran, Afghanistan. It has coastlines on the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea. People & Society Religion 96.0% Islam (Official) 1.85% Hinduism 1.5% Christianity 0.6% others ▪ The current population of Pakistan is 217,398,737 as of Friday, April 03, 2020, based on the latest United Nations estimates. -

Lahore & Karachi

The Travel Explorers EXPLORE PAKISTAN LAHORE & KARACHI www.thetravelexplorers.com DAY 01 Arrival and meet and greet at Islamabad Airport and then transfer to hotel. Islamabad is the capital and 9th largest city of Pakistan. It is located in the Pothohar Plateau. Islamabad is famous because of its cleanliness, calmness and greenery. Its noise-free atmosphere attracts not only the locals but the foreigners as well. Islamabad has a subtropical climate and one can enjoy all four seasons in this city. Rawalpindi is close to Islamabad and together they are known as the twin cities. In the afternoon half day city tour. We will visit Pakistan Monument located on the Shakarparian Hills in Islamabad. It was established in 2010. This monument serves as the tribute to the people who surrendered their lives and fought for the independence of Pakistan. The monument is of a shape of a blooming flower. There are four large petals which represents the four provinces of Pakistan i.e. Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. There are also three small petals which represents Azad Jammu & Kashmir, FATA and Gilgit Baltistan. There are breathtaking murals on the inner walls of the monument like the murals of Faisal Mosque, Makli Tombs, Gawadar, Quaid-e-Azam, Fatima Jinnah, Badshahi Mosque etc. This monument provides significance of the Pakistani culture, history and lineage. Later we will visit Faisal Mosque which is located near Margalla Hills in Islamabad. It is one of the major tourist attractions in Pakistan. Faisal Bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud granted $120 million in 1976 for the construction of the mosque. -

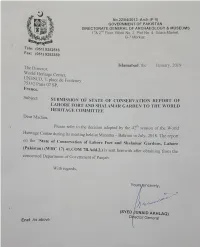

State of Conservation Report by The

Report on State of Conservation of World Heritage Property Fort & Shalamar Gardens Lahore, Pakistan January, 2019 Government of the Punjab Directorate General of Archaeology Youth Affairs, Sports, Archaeology and Tourism Department Table of Contents Sr. Page Item of Description No. No. 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Introduction 3 3. Part-1. Report on decision WHC/18/42.COM/7B.14 5 4. Part-2. Report on State of Conservation of Lahore Fort 13 5. Report on State of Conservation of Shalamar Gardens 37 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Fort & Shalamar Gardens in Lahore, Pakistan were inscribed on the World Heritage List of monuments in 1981. The state of Conservation of the Fort and Shalamar Gardens were discussed in the 42nd Session of the World Heritage Committee (WHC) in July, 2018 at Manama, Bahrain. In that particular session the Committee took various decisions and requested the State Party to implement them and submit a State of Conservation Report to the World Heritage Centre for its review in the 43rd Session of the World Heritage Committee. The present State of Conservation Report consists of two parts. In the first part, progress on the decisions of the 42nd Session of the WHC has been elaborated and the second part of the report deals with the conservation efforts of the State Party for Lahore Fort and Shalamar Gardens. Regarding implementation of Joint World Heritage Centre/ICOMOS Reactive Monitoring Mission (RMM) recommendations, the State Party convened a series of meetings with all the stakeholders including Federal Department of Archaeology, UNESCO Office Islamabad, President ICOMOS Pakistan, various government departments of the Punjab i.e., Punjab Mass-Transit Authority, Lahore Development Authority, Metropolitan Corporation of Lahore, Zonal Revenue Authorities, Walled City of Lahore Authorities, Technical Committee on Shalamar Gardens and eminent national & international heritage experts and deliberated upon the recommendations of the RMM and way forward for their implementation. -

List of Holdings Contains All Available Records and Is Revised Periodically As and When More Records Are Processed Into the NCAA

HISTORY OF THE PROJECT The National College of Arts Archives (NCAA) is the repository of the non-current records of the institution, dating back to its inception in 1875 as the Mayo School of Arts (MSA), Lahore. It has been set up as a result of the Project for the Conservation and Cataloguing of Old Records, started in the summer of 1999 in preparation of the 125th anniversary of the National College of Arts (NCA), Lahore. Under the Project, records of the institution were retrieved from various sources and collection was processed initially with the help of students and staff of the college. Later, Punjab Archives, Lahore and Conservation Laboratory, Lahore Museum assisted in the conservation and development of the Archives Project. The records in the NCAA have an enduring historical and research value and form an important part of the institution’s corporate memory and can easily be accessed for research purposes. OBJECTIVES ▪ To access non-current records of MSA/NCA which have research and historical value. ▪ To search, locate, preserve and conserve the records and art artifacts of enduring historical significance ▪ To advise researchers and students on the use of records for research purposes. ▪ To advise researchers on the location of non-public records, art artifacts and manuscripts relating to the arts and crafts history of Pakistan. ▪ To facilitate the publication of such material in liaison with the Research and Publication Center (RPC), NCA. RECORD HOLDINGS Spreading over a century and a quarter, the records in the NCAA consist of typed and hand- written papers, maps, charts, photographs and other physical items.