PRE-HISPANIC CENTRAL MEXICAN HISTORIOGRAPHY One of Tlie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Humanoid Robot

NAIN 1.0 – A HUMANOID ROBOT by Shivam Shukla (1406831124) Shubham Kumar (1406831131) Shashank Bhardwaj (1406831117) Department of Electronics & Communication Engineering Meerut Institute of Engineering & Technology Meerut, U.P. (India)-250005 May, 2018 NAIN 1.0 – HUMANOID ROBOT by Shivam Shukla (1406831124) Shubham Kumar (1406831131) Shashank Bhardwaj (1406831117) Submitted to the Department of Electronics & Communication Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Technology in Electronics & Communication Meerut Institute of Engineering & Technology, Meerut Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam Technical University, Lucknow May, 2018 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning except where due acknowledgment has been made in the text. Signature Signature Name: Mr. Shivam Shukla Name: Mr. Shashank Bhardwaj Roll No. 1406831124 Roll No. 1406831117 Date: Date: Signature Name: Mr. Shubham Kumar Roll No. 1406831131 Date: ii CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Project Report entitled “Humanoid Robot” which is submitted by Shivam Shukla (1406831124), Shashank Bhardwaj (1406831117), Shubahm Kumar (1406831131) in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of degree B.Tech in Department of Electronics & Communication Engineering of Gautam Buddh Technical University (Formerly U.P. Technical University), is record of the candidate own work carried out by him under my/our supervision. The matter embodied in this thesis is original and has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. -

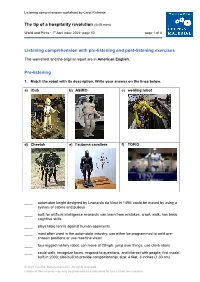

The Tip of a Hospitality Revolution (5:48 Mins) Listening Comprehension with Pre-Listening and Post-Listening Exercises Pre-List

Listening comprehension worksheet by Carol Richards The tip of a hospitality revolution (5:48 mins) World and Press • 1st April issue 2021• page 10 page 1 of 8 Listening comprehension with pre-listening and post-listening exercises This worksheet and the original report are in American English. Pre-listening 1. Match the robot with its description. Write your answer on the lines below. a) iCub b) ASIMO c) welding robot d) Cheetah e) l’automa cavaliere f) TOPIO ____ automaton knight designed by Leonardo da Vinci in 1495; could be moved by using a system of cables and pulleys ____ built for artificial intelligence research; can learn from mistakes, crawl, walk; has basic cognitive skills ____ plays table tennis against human opponents ____ most often used in the automobile industry; can either be programmed to weld pre- chosen positions or use machine vision ____ four-legged military robot, can move at 28mph, jump over things, use climb stairs ____ could walk, recognize faces, respond to questions, and interact with people; first model built in 2000; also built to provide companionship; size: 4 feet, 3 inches (1.30 cm) © 2021 Carl Ed. Schünemann KG. All rights reserved. Copies of this material may only be produced by subscribers for use in their own lessons. The tip of a hospitality revolution World and Press • April 1 / 2021 • page 10 page 2 of 8 2. Vocabulary practice Match the terms on the left with their German meanings on the right. Write your answers in the grid below. a) billion A Abfindung b) competitive advantage B auf etw. -

Stear Dissertation COGA Submission 26 May 2015

BEYOND THE FIFTH SUN: NAHUA TELEOLOGIES IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES By ©Copyright 2015 Ezekiel G. Stear Submitted to the graduate degree program in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Santa Arias ________________________________ Verónica Garibotto ________________________________ Patricia Manning ________________________________ Rocío Cortés ________________________________ Robert C. Schwaller Date Defended: May 6, 2015! ii The Dissertation Committee for Ezekiel G. Stear certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BEYOND THE FIFTH SUN: NAHUA TELEOLOGIES IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES ________________________________ Chairperson, Santa Arias Date approved: May 6, 2015 iii Abstract After the surrender of Mexico-Tenochtitlan to Hernán Cortés and his native allies in 1521, the lived experiences of the Mexicas and other Nahuatl-speaking peoples in the valley of Mexico shifted radically. Indigenous elites during this new colonial period faced the disappearance of their ancestral knowledge, along with the imposition of Christianity and Spanish rule. Through appropriations of linear writing and collaborative intellectual projects, the native population, in particular the noble elite sought to understand their past, interpret their present, and shape their future. Nahua traditions emphasized balanced living. Yet how one could live out that balance in unknown times ahead became a topic of ongoing discussion in Nahua intellectual communities, and a question that resounds in the texts they produced. Writing at the intersections of Nahua studies, literary and cultural history, and critical theory, in this dissertation I investigate how indigenous intellectuals in Mexico-Tenochtitlan envisioned their future as part of their re-evaluations of the past. -

Design of a Drone with a Robotic End-Effector

Design of a Drone with a Robotic End-Effector Suhas Varadaramanujan, Sawan Sreenivasa, Praveen Pasupathy, Sukeerth Calastawad, Melissa Morris, Sabri Tosunoglu Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering Florida International University Miami, Florida 33174 [email protected], [email protected] , [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT example, the widely-used predator drone for military purposes is the MQ-1 by General Atomics which is remote controlled, UAVs The concept presented involves a combination of a quadcopter typically fall into one of six functional categories (i.e. target and drone and an end-effector arm, which is designed with the decoy, reconnaissance, combat, logistics, R&D, civil and capability of lifting and picking fruits from an elevated position. commercial). The inspiration for this concept was obtained from the swarm robots which have an effector arm to pick small cubes, cans to even With the advent of aerial robotics technology, UAVs became more collecting experimental samples as in case of space exploration. sophisticated and led to development of quadcopters which gained The system as per preliminary analysis would contain two popularity as mini-helicopters. A quadcopter, also known as a physically separate components, but linked with a common quadrotor helicopter, is lifted by means of four rotors. In operation, algorithm which includes controlling of the drone’s positions along the quadcopters generally use two pairs of identical fixed pitched with the movement of the arm. propellers; two clockwise (CW) and two counterclockwise (CCW). They use independent variation of the speed of each rotor to achieve Keywords control. -

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT for DISTRIBUTION Figure 0.3

Contents Acknowledgments ix A Brief Note on Usage xiii Introduction: History and Tlaxilacalli 3 Chapter 1: The Rise of Tlaxilacalli, ca. 1272–1454 40 Chapter 2: Acolhua Imperialisms, ca. 1420s–1583 75 Chapter 3: Community and Change in Cuauhtepoztlan Tlaxilacalli, ca. 1544–1575 97 Chapter 4: Tlaxilacalli Religions, 1537–1587 123 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Chapter 5: TlaxilacalliNOT FOR Ascendant, DISTRIBUTION 1562–1613 151 Chapter 6: Communities Reborn, 1581–1692 174 Conclusion: Tlaxilacalli and Barrio 203 List of Acronyms Used Frequently in This Book 208 Bibliography 209 Index 247 vii introduction History and Tlaxilacalli This is the story of how poor, everyday central Mexicans built and rebuilt autono- mous communities over the course of four centuries and two empires. It is also the story of how these self-same commoners constructed the unequal bonds of compul- sion and difference that anchored these vigorous and often beloved communities. It is a story about certain face-to-face human networks, called tlaxilacalli in both singular and plural,1 and about how such networks molded the shape of both the Aztec and Spanish rule.2 Despite this influence, however, tlaxilacalli remain ignored, subordinated as they often were to wider political configurations and most often appearing unmarked—that is, noted by proper name only—in the sources. With care, however, COPYRIGHTEDthe deeper stories of tlaxilacalli canMATERIAL be uncovered. This, in turn, lays bare a root-level history of autonomy and colonialism in central Mexico, told through the powerfulNOT and transformative FOR DISTRIBUTION tlaxilacalli. The robustness of tlaxilacalli over thelongue durée casts new and surprising light on the structures of empire in central Mexico, revealing a counterpoint of weakness and fragmentation in the canonical histories of centralizing power in the region. -

The Finding and Founding of Mexico Tenochtitlan

THE FINDING AND FOUNDING OF MEXICO TENOCHTITLAN From the Crónica Mexicayotl, by Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc Translation and notes by Thelma D. Sullivan TRANSLATOR'S NOTE The Crónica Mexicayotl, written in 1609 by Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc, a grandson of Moctezuma on his mother's side and a great grandson of Axayacati on his father's, is one of the great documents of Nahuatl lore. His account of the emergence of the Aztecs from Aztlan-Chicomortoc, their peregrinations and the vicissitudes of their fortune while being driven on by their god, Hnizilopochtli, until they finally reached Tenochtitlan is not only a mine of mythico-historical data but also a saga of true literary merit and heroic dimensions. In the translation I am offering here, which as far as I know is the first in English, I have selected and threaded together only those texts which, in my opinion, narrate the events that directly led the Aztecs to the finding of their promised land. I have not, in any way, altered the sequence of events as they appear in the text. A Spanish translation of the Crónica Mexicayotl by Adrián León was published by the UNAM in 1949. In the opinion of A. M. Garibay, León's translation ". no da al público en general la com- prensión exigida, ya no solamente para aprovechar el dato escueto para la historia, pero ni siquiera la recta inteligencia del texto:"* Nahuatl scholars who compare the two versions will discover some differences between mine and León's, and I believe that my translation will clarify a number of texts that have long puzzled them. -

Surveillance Robot Controlled Using an Android App Project Report Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

Surveillance Robot controlled using an Android app Project Report Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Engineering by Shaikh Shoeb Maroof Nasima (Roll No.12CO92) Ansari Asgar Ali Shamshul Haque Shakina (Roll No.12CO106) Khan Sufiyan Liyaqat Ali Kalimunnisa (Roll No.12CO81) Mir Ibrahim Salim Farzana (Roll No.12CO82) Supervisor Prof. Kalpana R. Bodke Co-Supervisor Prof. Amer Syed Department of Computer Engineering, School of Engineering and Technology Anjuman-I-Islam’s Kalsekar Technical Campus Plot No. 2 3, Sector -16, Near Thana Naka, Khanda Gaon, New Panvel, Navi Mumbai. 410206 Academic Year : 2014-2015 CERTIFICATE Department of Computer Engineering, School of Engineering and Technology, Anjuman-I-Islam’s Kalsekar Technical Campus Khanda Gaon,New Panvel, Navi Mumbai. 410206 This is to certify that the project entitled “Surveillance Robot controlled using an Android app” is a bonafide work of Shaikh Shoeb Maroof Nasima (12CO92), Ansari Asgar Ali Shamshul Haque Shakina (12CO106), Khan Sufiyan Liyaqat Ali Kalimunnisa (12CO81), Mir Ibrahim Salim Farzana (12CO82) submitted to the University of Mumbai in partial ful- fillment of the requirement for the award of the degree of “Bachelor of Engineering” in De- partment of Computer Engineering. Prof. Kalpana R. Bodke Prof. Amer Syed Supervisor/Guide Co-Supervisor/Guide Prof. Tabrez Khan Dr. Abdul Razak Honnutagi Head of Department Director Project Approval for Bachelor of Engineering This project I entitled Surveillance robot controlled using an android application by Shaikh Shoeb Maroof Nasima, Ansari Asgar Ali Shamshul Haque Shakina, Mir Ibrahim Salim Farzana,Khan Sufiyan Liyaqat Ali Kalimunnisa is approved for the degree of Bachelor of Engineering in Department of Computer Engineering. -

Rewriting Native Imperial History in New Spain: the Excot Can Dynasty Alena Johnson

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Spanish and Portuguese ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2016 Rewriting Native Imperial History in New Spain: The excoT can Dynasty Alena Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/span_etds Recommended Citation Johnson, Alena. "Rewriting Native Imperial History in New Spain: The excT ocan Dynasty." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/span_etds/24 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish and Portuguese ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Alena Johnson Candidate Spanish and Portuguese Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Miguel López, Chairperson Kimberle López Ray Hernández-Durán Enrique Lamadrid ii REWRITING NATIVE IMPERIAL HISTORY IN NEW SPAIN: THE TEXCOCAN DYNASTY by ALENA JOHNSON B.A., Spanish, Kent State University, 2002 M.A., Spanish Literature, Kent State University, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Spanish and Portuguese The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2015 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express much gratitude to each of my committee members for their mentorship, honorable support, and friendship: Miguel López, Associate Professor of Latin American Literature, Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of New Mexico; Kimberle López, Associate Professor of Latin American Literature, Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of New Mexico; Ray Hernández-Durán, Associate Professor of Early Modern Ibero-American Colonial Arts and Architecture, Department of Art and Art History, University of New Mexico; and Enrique Lamadrid, Professor Emeritus, Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of New Mexico. -

Cortés After the Conquest of Mexico

CORTÉS AFTER THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO: CONSTRUCTING LEGACY IN NEW SPAIN By RANDALL RAY LOUDAMY Bachelor of Arts Midwestern State University Wichita Falls, Texas 2003 Master of Arts Midwestern State University Wichita Falls, Texas 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2013 CORTÉS AFTER THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO: CONSTRUCTING LEGACY IN NEW SPAIN Dissertation Approved: Dr. David D’Andrea Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael Smith Dr. Joseph Byrnes Dr. James Cooper Dr. Cristina Cruz González ii Name: Randall Ray Loudamy Date of Degree: DECEMBER, 2013 Title of Study: CORTÉS AFTER THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO: CONSTRUCTING LEGACY IN NEW SPAIN Major Field: History Abstract: This dissertation examines an important yet woefully understudied aspect of Hernán Cortés after the conquest of Mexico. The Marquisate of the Valley of Oaxaca was carefully constructed during his lifetime to be his lasting legacy in New Spain. The goal of this dissertation is to reexamine published primary sources in light of this new argument and integrate unknown archival material to trace the development of a lasting legacy by Cortés and his direct heirs in Spanish colonial Mexico. Part one looks at Cortés’s life after the conquest of Mexico, giving particular attention to the themes of fame and honor and how these ideas guided his actions. The importance of land and property in and after the conquest is also highlighted. Part two is an examination of the marquisate, discussing the key features of the various landholdings and also their importance to the legacy Cortés sought to construct. -

Communicating Simulated Emotional States of Robots by Expressive Movements

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Sial, Sara Baber (2013) Communicating simulated emotional states of robots by expressive movements. Masters thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/12312/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

The 52-Year Calendar of the Aztecs in the Postclassic Period 231 The

the 52-year calendar of the aztecs in the postclassic period 231 Chapter Four THE rITUAL PRACtICe oF tIMe oF THE 52-YEAR CaLeNDAR oF THE POStCLaSSIC aZTEC CIVILISATIoN It is from the Nahuatl-speaking Nahua culture called aztec, or Mexica1 as they called themselves; primary data of the ritual practice of time of the 52-year calendar are still in existence. I do not claim, however, that the Mesoamerican 52-year calendar or its associated ritual practices only ex- isted in aztec or Nahua society and culture. the term “aztec”2 derives from aztecatl,”person from aztlán”. aztlán— which can be paraphrased as “the white place” or “the place of the herons” in Nahuatl—was the designation for their place of origin. the aztecs con- stituted a part of the last Nahua faction whom invaded the Basin of Mexi- co after the decline of the toltecs (probably around 1100 AD) after leaving their place of origin (aztlán or Chicomoztoc).3 Not only their name but in addition their identity was hence transformed from chichimec4 when the aztecs founded the city tenochtitlan in 1325 AD (1 Calli according to their 52-year calendar), today known as Mexico City, on a few islands at the western part of the tetzcoco lake in the valley of Mexico. this became the capital of their transient realm in the northern and central part of Mexico from 1325 AD to 1521 AD (López austin 2001; Quiñones Keber 2002: 17). a triple alliance called excan tlatoloyan (“tribunal of three places”)—com- prising the cities tenochtitlan, tetzcoco and tlacopan—was established in 1428 AD by the regents Itzcoatl of tenochtitlan, Nezahualcóyotl of tetzco- co and totoquihuatzin of tlacopan. -

Inter·American Tropical Tuna Commission

INTER·AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION Special Report No.5 ORGANIZATION, FUNCTIONS, AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE t INTER-AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION I ~. t I, ! by i ~ Clifford L. Peterson and William H. Bayliff Ii f I I t La Jolla, California 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION. • 1 AREA COVERED BY THE CONVENTION. 1 SPECIES COVERED BY THE CONVENTION AND SUBSEQUENT INSTRUCTIONS 3 Yellowtin tuna • 3 Skipjack tuna. 3 Northern bluetin tuna. 4 Other tunas. 5 Billtishes 6 Baittishes 6 Dolphins • 7 ORGANIZATION. 7 Membership • 7 Languages. 8 Commissioners. 8 Meetings 8 Chairman and secretary 9 Voting • 9 Director of investigations and statf • 9 Headquarters and field laboratories. 10 Finance. 10 RESEARCH PROGRAM. 11 Fish • 11 Fishery statistics. 12 Biology of tunas and billtishes • 14 Biology ot baittishes • 16 Oceanography and meteorology. 16 Stock assessment. 17 Dolphins • • • 19 Data collection • 19 Population assessment • • 20 Attempts to reduce dolphin mortality. • 21 Interactions between dolphins and tunas • 22 REGULATIONS • 22 INTERGOVERNMENTAL MEETINGS. 26 RELATIONS WITH OTHER ORGANIZATIONS. • 27 International. • 27 National • 27 Intranational • • 28 PUBLICATIONS. • • 29 LITERATURE CITED. • 30 FIGURE. • 31 TABLES. • • • 32 APPENDIX 1. • • 35 APPENDIX 2. • 43 INTRODUCTION The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) operates under the authority and direction of a Convention originally entered into by the governments of Costa Rica and the United states. The Convention, which came into force in 1950, is open to the adherence by other governments whose nationals participate in the fisheries for tropical tunas in the eastern Pacific Ocean. The member nations of the Commission now are France. Japan, Nicaragua. Panama, and the United States.