The Aristocracy of Leon-Castile in the Reign Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guiteras, Wardwell· and Allied Families

GUITERAS, WARDWELL· AND ALLIED FAMILIES GENEALOGICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL - Prepared and Privately Printed for GEllTRUDE ELIZABETH GUITERAS BY THE AMElUCAN HISTOlllCAL SOCIETY, lac. NEW YC>IU( 1926 ·Bt> IC)llJfl f> Jt · Jn l)euoteb ~emo~ of llanlon ~uitnas II)tt Satbn, tuottl)p scion of a Distin== gufsbeb .Dlb morlb Samilp, 4tliJabetl, eanrteitn (lllatb\llrll) •uiterai Ott •otber, of like gentle llittb, be== sunbant of manp notallle colonial Smttican lines, anb · l>r. l\amen •uittraf lilbose ricb professional talents were unsparinglp useb in tilt serttiu of bis -ftllotu men, ~bis tJolume is JDellicattb fl1! en~rutJe eri;alJttf) ~tritera, ~ & ~ ~ ~ ~ " j:$' ~~ ~ GUITERAS ARMS Arms-Vert, five greyhounds' heads erased proper, vulned, and distilling drops of blood gules, posed two, one and two. Guiteras HE Guiteras family of Rhode Island ( which lineage was transplanted from Spain by way of Cuba) was long notably distinguished in Spain before the removal of a scion thereof to the Island of Cuba, in which lat~er vicinity it maintained without diminution the honor of its ancestry, and removing thence to the United States, in unbroken continuity has flourished in excellence in that land of its adoption. II DON MATEO GUITERAS, son of Don Juan Guiteras, ancestor of the Rhode Island line, was a native of Canet Le Mar, Spain. He died in Spain. His son, Don Mateo Guiteras, married Dofia Maria De Molins. (See De Molins.) Their son; Ramon, of whom further. III RAM6N GUITERAS was born at Canet Le Mar, Spain, in 1775, and removed in early manhood to Cuba, where he engaged in mercantile pur suits; he acquireg extensive lands., which he devoted largely to the cultiva tion of coffee, and had his residence at Matanzas, on that Island. -

La Conquista Y El Imperio En Los Reinados De Alfonso VI Y Alfonso VII” P

Hélène Sirantoine “Exclusión e integración: la conquista y el imperio en los reinados de Alfonso VI y Alfonso VII” p. 321-354 El mundo de los conquistadores Martín F. Ríos Saloma (edición) México Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas / Silex Ediciones 2015 864 p. Ilustraciones (Serie Historia General, 34) ISBN 978-607-02-7530-2 (UNAM) ISBN 978-84-7737-888-4 (Sílex) Formato: PDF Publicado en línea: 8 de mayo de 2017 Disponible en: http://www.historicas.unam.mx/publicaciones/publicadigital /libros/mundo/conquistadores.html DR © 2017, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas. Se autoriza la reproducción sin fines lucrativos, siempre y cuando no se mutile o altere; se debe citar la fuente completa y su dirección electrónica. De otra forma, se requiere permiso previo por escrito de la institución. Dirección: Circuito Mtro. Mario de la Cueva s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510. Ciudad de México EXCLUSIÓN E INTEGRACIÓN: LA CONQUISTA Y EL IMPERIO EN LOS REINADOS DE ALFONSO VI Y ALFONSO VII• Hélène Sirantoine University of Sidney, SOPHI, Department of History INTRODUCCIÓN Con anterioridad al imperio español en América, existió en la España medieval otro imperio, aunque tuvo un alcance mucho menor. Lo que con ostentación llamamos «imperio hispánico me- dieval» hace referencia al título de imperator que fue atribuido a unos cuantos reyes asturleoneses y luego castellanoleoneses de los siglos ix a xii, así como al aparato imperial con los que fue caracte- rizado su poder. Al principio el fenómeno fue más bien algo pun- tual. Posteriormente adquirió un desarrollo más efectivo, con los reinados de dos soberanos en particular: Alfonso VI (1065-1109), y su nieto Alfonso VII (1126-1157), que fueron ambos reyes de Cas- tilla y León y «emperadores de toda Hispania» (imperatores totius Hispaniae). -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Lordship of Negroponte

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1d/LatinEmpire2.png Lordship of Negroponte From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2007) Lordship of Negroponte Nigropont Client state* 1204–1470 → ← The Latin Empire with its vassals and the Greek successor states after the partition of the Byzantine Empire, c. 1204. The borders are very uncertain. Capital Chalkis (Negroponte) Venetian officially, Language(s) Greek popularly Roman Catholic Religion officially, Greek Orthodox popularly Political structure Client state Historical era Middle Ages - Principality 1204 established - Ottoman Conquest 1470 * The duchy was nominally a vassal state of, in order, the Kingdom of Thessalonica, the Latin Empire (from 1209), the Principality of Achaea (from 1236), but effectively, and from 1390 also de jure, under Venetian control The Lordship of Negroponte was a crusader state established on the island of Euboea (Italian: Negroponte) after the partition of the Byzantine Empire following the Fourth Crusade. Partitioned into three baronies (terzieri) run by a few interrelated Lombard families, the island soon fell under the influence of the Republic of Venice. From ca. 1390, the island became a regular Venetian colony as the Kingdom of Negroponte (Regno di Negroponte). Contents • 1 History o 1.1 Establishment o 1.2 Succession disputes o 1.3 Byzantine interlude o 1.4 Later history • 2 List of rulers of Negroponte o 2.1 Triarchy of Oreos o 2.2 Triarchy of Chalkis o 2.3 Triarchy of Karystos • 3 References • 4 Sources and bibliography History Establishment According to the division of Byzantine territory (the Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae), Euboea was awarded to Boniface of Montferrat, King of Thessalonica. -

XVIII / 2020 Una Riflessione Sulla Tenencia, Elemento Chiave Nel

I quaderni del m.æ.s. – XVIII / 2020 Una riflessione sulla tenencia, elemento chiave nel rapporto politico tra Alfonso VII di Leon e Castiglia (1126-1157) e i suoi magnati Sonia Vital Fernández Abstract: Nella Penisola iberica, come pure si verifica in altre regioni europee nel XII secolo, si osserva un’aristocrazia che detiene importanti basi patrimoniali, molto dinamica e capace di diversificare le proprie risorse e strategie, estendendo la sua influenza e i suoi interessi in molte regioni. Il suo potere, quindi, era in grado di sfidare l'autorità stessa del re. Data questa realtà, Alfonso VII di Leon e Castiglia cercò di consolidare e rafforzare l'autorità regia che era stata minata nella fase precedente e di ricuperare la potestas publica. Così, negoziò con l'aristocrazia, cercando di includerla nel suo progetto politico, ma controllando ed equilibrando il potere che esercitava. Il migliore scenario per osservare tale politica è offerto dal sistema amministrativo delle tenencias. Alfonso VII; aristocrazia; Penisola iberica; potere; XII secolo In the Iberian Peninsula, as it is clear in other regions of Europe in the twelfth century, there was an aristocracy with important patrimonial basis, very dynamic and able to diversify their resources and strategies, extending its influence and interests in many regions. Therefore, its power was able to challenge the authority of the king. Given this reality, Alfonso VII of Leon and Castile tried to consolidate and strengthen the royal authority that had been undermined in the previous years and got back the potestas publica. Then he negotiated with the aristocracy, trying to include it in his political project, but checking and balancing the power it wielded. -

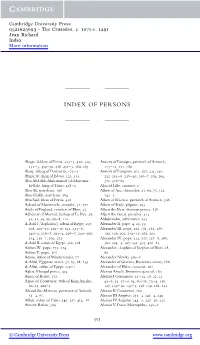

Index of Persons

Cambridge University Press 0521623693 - The Crusades, c. 1071-c. 1291 Jean Richard Index More information ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ INDEX OF PERSONS ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ Abaga, il-khan of Persia, 423±4, 426, 429, Aimery of Limoges, patriarch of Antioch, 432±3, 439±40, 446, 452±3, 460, 463 113±14, 171, 180 Abaq, atabeg of Damascus, 173±4 Aimery of Lusignan, 201, 207, 225, 230, Abgar, St, king of Edessa, 122, 155 232, 235±6, 238±40, 256±7, 264, 294, Abu Abdallah Muhammad (al-Mustansir 371, 376±80 bi-llah), king of Tunis, 428±9 Alan of Lille, canonist, 2 Abu Ali, merchant, 106 Albert of Aix, chronicler, 21, 69, 75, 123, Abu Ghalib, merchant, 384 142±3 Abu Said, khan of Persia, 456 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Antioch, 396 Achard of Montmerle, crusader, 31, 271 Albert of Stade, pilgrim, 293 Adela of England, countess of Blois, 35 Albert the Bear, German prince, 158 AdheÂmar of Monteil, bishop of Le Puy, 28, Albert the Great, preacher, 413 32, 42, 49, 60, 66±8, 112 Aldobrandin, adventurer, 254 al-Adil I (`Saphadin'), sultan of Egypt, 197, Alexander II, pope, 4, 23, 39 208, 209±10, 229±30, 232, 235±6, Alexander III, pope, 122, 181, 185, 188, 240±2, 256±7, 293±4, 296±7, 299±300, 190, 199, 202, 214±15, 260, 292 314, 350±1, 362, 375 Alexander IV, pope, 335, 337, 357±8, 360, al-Adil II, sultan of Egypt, 322, 328 362, 364±5, 367, 391, 397, 410±13 Adrian IV, pope, 175, 214 Alexander, chaplain of Stephen of Blois, 28, Adrian V, pope, 385 60 Adson, abbot of MontieÂrender, 17 Alexander Nevski, 360±1 al-Afdal, Egyptian vizier, 57, 65, 68, 139 Alexander of Gravina, -

SIGLOS X-XII) Studia Historica, Historia Medieval, Vol

Studia Historica, Historia Medieval ISSN: 0213-2060 [email protected] Universidad de Salamanca España PÉREZ RODRÍGUEZ, María CASTROFROILA: LA REPRESENTACIÓN DEL PODER CENTRAL EN LA RIBERA DEL CEA (SIGLOS X-XII) Studia Historica, Historia Medieval, vol. 33, 2015, pp. 173-199 Universidad de Salamanca Salamanca, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=367544750007 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto ISSN: 0213-2060 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14201/shhme201533173199 CASTROFROILA: LA REPRESENTACIÓN DEL PODER CENTRAL EN LA RIBERA DEL CEA (SIGLOS X-XII)1 Castrofroila: the Portrayal of the Central Power in the Cea’s Bank (10th-12th Centuries) María PÉREZ RODRÍGUEZ Depto. de Historia Medieval, Moderna y Contemporánea. Facultad de Geografía e Historia. Universidad de Salamanca. C/ Cervantes, s/n. E-37002 Salamanca. C. e.: [email protected] Recibido: 2013-07-25 Revisado: 2014-03-31 Aceptado: 2014-10-03 RESUMEN: Sin descartar la diversidad de funciones tradicionalmente atribuidas a castros y castillos, en los últimos años se ha incidido sobre todo en su papel como centros de representación del poder. El ejemplo que aquí presentamos viene caracterizado por la fuerte y continua vinculación que se establece entre Castro Froila–Mayorga, en la ribera del Cea, y la autoridad central. A través de las fuentes documentales y arqueológicas sabemos de la exis- tencia de este enclave y de la importante función política que desde él se ejerció, intensificada tras la división del reino a la muerte de Alfonso VII y el recrudecimiento del conflicto entre León y Castilla. -

Archbishop of Lund

INDEX Abodrites, see Slavs Alfonso VII, king of Castile (1126–57), Absalon, bishop of Roskilde (1158–92), 31–2, 35 archbishop of Lund (1177–1201), 47 Alfonso VIII, king of Castile Adalbert, archbishop of Hamburg- (1158–1214), 156–7 Bremen (1043–72), 29 Alfonso Henriques, king of Portugal Adalbert Vojt^ch, bishop of Prague (1139–85), 35 (983–97), 81 Alfonso Jordan, count of Toulouse Adam of Bremen, chronicler (d. before (d. 1148), 35 1085), 13, 29 Almeria, 35–6 Adolf, count of Holstein (d. 1164), 35 Alvis, bishop of Arras (1134–47), 34 Adrian IV, pope (1154–9), 34, 51 Amadeus III, count of Savoy Alberic of Trois-Fontaines, chronicler (1103–48), 34–5 (d. after 1251), 175 Anastasius IV, pope (1153–4), 63–4 Albert (Suerbeer), archbishop of Riga Anders (Sunesen), archbishop of Lund (1253/55–1273), 230–1, 233, 243 (1201–22) Albert (of Buxhövden), bishop of and crusades to the Holy Land, Livonia (1199–1229), 80, 187 87–8, 101 n. 82 and the Danes, 133–4 and the curia, 85–6, 88–9, 152, and the ecclesiastical organization, 157, 160 n. 112, 250 123, 125–6, 171, 181–2 and Estonia, 85, 123–4, 157 and Emperor Frederick II, 203–4 and Finland, 82–3, 126 and Henry of Livonia, 14 and mission, 82–3, 86 and the new converts, 117–19 legatine powers of, 126–7 and the Sword-Brothers, 80–1, 134 Andrew II, king of Hungary (1205–35), and William of Modena, see William, 158–9, 189 n. 10 bishop of Modena Anselm, bishop of Havelberg (d. -

Sandell2020.Pdf (2.860Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Muslim Men in the Imagination of the Medieval West, c. 1000 – c. 1250 Malin Sandell PhD History The University of Edinburgh 2018 1 Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 4 List of Illustrations .................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction. The Saracen Man in the Present and the Past ................................................. 8 The Present .......................................................................................................................... 8 Historiography ................................................................................................................... -

The Election of Arnau De Torroja As Ninth Master of the Knights Templar (1180): an Enigmatic Decision Reconsidered

The election of Arnau de Torroja as ninth Master of the Knights Templar (1180): An enigmatic decision reconsidered Nikolas Jaspert (Ruhr-Universitat Bochum) Ever since Saladin took power in 1174, the Crusader States had 1 been slipping deeper and deeper into a serious crisis, a crisis which inevitably would also affect its most lasting creation, the military orders. In fact, the orders and their officials were an inextricable part of the struggle for power which would have such disastrous effects on the kingdom. Two dignitaries in particular stood in the eye of the gathering storm - the Master of the Templars and the Master of the Hospitallers. It has been calculated that in the years immediately preceding the battle of Hattin, the two orders were by far the most important landholders, owning up to 35% of the soil, and their military strength conferred on 2 them a vital role in the defence of the realm. Evidently, their senior officials wielded considerable power. Although several overviews on the Templars and Hospitallers exist, some of them excellent, relatively little attention has been given to 1 On the political situation of the year 1180 in the Kingdom of Jerusalem: R. ROHRICHT, Geschichte des Konigreichs Jerusalem 1100-1291, Innsbruck 1898 (Repr. 1966), p. 388-451; M. W. BALDWIN, Raymond III of Tripolis and the fall of Jerusalem (1140- 1187), Princeton 1936, Repr. Amsterdam 1969; P. W. EDBURY / J. G. ROWE, William of Tyre. Historian of the Latin East (Cambridge Studies in medieval life and thought, Fourth series 8), Cambridge 1988; H. E. MAYER, Geschichte der Kreuzziige (Urban- Taschenbiicher 86), 10. -

Read Transcript

History of the Crusades. Episode 36. The Second Crusade VIII. Hello again. Last week we saw the Crusaders arrive in the Holy Land. King Louis and the remaining French Knights arrived in Antioch, while King Conrad sailed in from Constantinople, where he had been recuperating from an arrow wound to his head which he suffered in Anatolia. The southern French fleets, complete with fresh men, arrived in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, as did the ships containing the Latin Christians who had taken Lisbon in Portugal. At the conclusion of last week's episode, we learned that a decision had been made for the Crusaders to attack Damascus. We'll come to that decision in a minute. But first I have a sad tale to tell you all. Remember Alfonso Jordan, Count of Toulouse? He's the son of Raymond, Count of Toulouse, founder of the Crusader state of Tripoli. Alfonso Jordan fled Tripoli as a baby after the death of his father, and went on to become Count of the wealthy region of Toulouse in France. Toulouse borders the Mediterranean Sea on the southern coast of France, and Alfonso Jordan and his contingent of knights very sensibly decided to sail to the Holy Land. Alfonso Jordan sailed into Acre in April 1148. His arrival was heralded by the Christian citizens of the County of Tripoli, who were eager to welcome back into the fold the son of their founder, who had, after all, been born in the region. But there were people who were not so keen to welcome Alfonso Jordan, and they of course, were the current Count of Tripoli, Raymond and his wife, the Countess Hodierna. -

Fuentes Históricas Y Legendarias Sobre La Conquista De Molina De Aragón Y Cronología Del Fuero” P.687-720

Nicolás Ávila Seoane “Fuentes históricas y legendarias sobre la conquista de Molina de Aragón y cronología del fuero” p.687-720 El mundo de los conquistadores Martín F. Ríos Saloma (edición) México Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas / Silex Ediciones 2015 864 p. Ilustraciones (Serie Historia General, 34) ISBN 978-607-02-7530-2 (UNAM) ISBN 978-84-7737-888-4 (Sílex) Formato: PDF Publicado en línea: 8 de mayo de 2017 Disponible en: http://www.historicas.unam.mx/publicaciones/publicadigital /libros/mundo/conquistadores.html DR © 2017, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas. Se autoriza la reproducción sin fines lucrativos, siempre y cuando no se mutile o altere; se debe citar la fuente completa y su dirección electrónica. De otra forma, se requiere permiso previo por escrito de la institución. Dirección: Circuito Mtro. Mario de la Cueva s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510. Ciudad de México FUENTES HISTÓRICAS Y LEGENDARIAS SOBRE LA CONQUISTA DE MOLINA DE ARAGÓN Y CRONOLOGÍA DEL FUERO Nicolás Ávila Seoane Departamento de Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas y Arqueología Universidad Complutense de Madrid El señorío inicial de Manrique de Lara sobre Molina de Aragón incluyó todos los pueblos del concejo, algunos de los cuales se fueron desgajando después por donaciones de la familia Lara o de los reyes de Castilla. Este territorio se dividió administrativamente en cuatro sexmas que aún seguían existiendo en época de Florida- blanca dentro del partido de Cuenca: «pueblos del mismo partido de Cuenca comprehendidos en el señorío de la villa de Molina y sus quatro sexmas»: la del Sabinar, la del Pedregal, la del Campo y la de la Sierra.