History of the Crusades. Episode 32. the Second Crusade IV. Hello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Early Turning Point in the History of the Crusades

Jonathan Phillips. The Second Crusade: Extending the Frontiers of Christendom. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. xxix + 364 pp. $40.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-300-11274-0. Reviewed by Jonathan R. Lyon Published on H-German (March, 2008) As the author makes clear in the excellent in‐ cepts could be employed against a variety of Latin troduction to this work, the Second Crusade Christendom's enemies. (1145-49) has typically not attracted as much in‐ Phillips divides his work into fourteen terest from modern historians as the more fa‐ chronologically-arranged chapters, although sepa‐ mous First Crusade (1095-99) and Third Crusade rate chapters treat the Iberian and Baltic compo‐ (1188-92). A key explanation for this trend is the nents of the crusade. The frst two chapters dis‐ Second Crusade's failure to make any significant cuss the period between the First and the Second gains for the Christians of the Holy Land in the Crusade; chapter 1 focuses on the various pilgrim‐ wake of the Muslim conquest of Edessa in 1144. ages and crusading efforts of the early twelfth Nevertheless, as Phillips convincingly argues, this century, and chapter 2 provides a rich, fascinating crusade--despite its lack of success--demands discussion of the powerful legacy the First Cru‐ more attention than it has received for several sade left to Latin Christian culture in the decades reasons. It was the frst crusade to the Holy Land after 1099. Phillips persuasively argues that this to involve western European kings and thus legacy had a significant impact on recruiting for forced rulers to consider the consequences of the Second Crusade, because the generation of leaving their kingdoms for months (if not years) young nobles alive in the 1140s had grown up at a time. -

The Crusades: a Very Brief History

MEDIEVALISTS.NET MEDIEVAL STUDIES MAGAZINE The Medieval Magazine Issue 6 March 9, 2015 The Crusades: A Very Brief History Lady in the Lead Coffin Tower of London: Margaret Beaufort: Mother Revealed Ceremony of the Keys of King Henry VII 12 16 46 Venetian Prisons in the Middle Ages The Medievalverse March 9, 2015 Page 8 Venetian Prisons in the Middle Ages Taking a look at how a Venetian prison on the island of Crete operated. Page 12 Lady in the Lead Coffin Revealed A mysterious lead coffin found close to the site of Richard III's hastily dug grave at the Grey Friars friary has been opened and studied by experts from the University of Leicester. Page 18 The Crusades Andrew Latham traces the contours of the specific types of violent religious conflict always immanent within the historical structure of medieval war. Page 44 Medieval Historical Fiction: Ten Novels from the 19th century Historical fiction was just beginning as literary genre in the 19th century, but soon authors found success in writing about stories set in the Middle Ages. Table of Contents 4 Quiz: How Well Do You Know the Seventh-Century? 6 Medieval Mass Grave Discovered n Paris 8 Venetian Prisons in the Middle Ages 11 Knight buried at Hereford Cathedral may have had jousting injuries, archaeologists find 12 Lady in the Lead Coffin revealed 15 Medieval Articles 16 Tower of London – The Ceremony of the Keys 18 The Crusades: A Very Brief History, 1095-1500 42 The Mazims of Francesco Guicciardini 44 The Beginning of Medieval Historical Fiction: Ten Novels from the 19th century 46 Margaret Beaufort, Mother of King Henry VII 50 Medieval Videos The Medievalverse The weekly digital magazine from Medievalists.net Edited by Peter Konieczny and Sandra Alvarez Cover: Crusaders storm Jerusalem, from The Hague, MMW, 10 A 21 How Well Do You Know the Seventh Century? 1.This Anglo-Saxon helmet, which dates from the early 7th century, was found at which archaeological site? 2. -

Crusading, the Military Orders, and Sacred Landscapes in the Baltic, 13Th – 14Th Centuries ______

TERRA MATRIS: CRUSADING, THE MILITARY ORDERS, AND SACRED LANDSCAPES IN THE BALTIC, 13TH – 14TH CENTURIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the School of History, Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in History & Welsh History (2018) ____________________________________ by Gregory Leighton Abstract Crusading and the military orders have, at their roots, a strong focus on place, namely the Holy Land and the shrines associated with the life of Christ on Earth. Both concepts spread to other frontiers in Europe (notably Spain and the Baltic) in a very quick fashion. Therefore, this thesis investigates the ways that this focus on place and landscape changed over time, when crusading and the military orders emerged in the Baltic region, a land with no Christian holy places. Taking this fact as a point of departure, the following thesis focuses on the crusades to the Baltic Sea Region during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It considers the role of the military orders in the region (primarily the Order of the Teutonic Knights), and how their participation in the conversion-led crusading missions there helped to shape a distinct perception of the Baltic region as a new sacred (i.e. Christian) landscape. Structured around four chapters, the thesis discusses the emergence of a new sacred landscape thematically. Following an overview of the military orders and the role of sacred landscpaes in their ideology, and an overview of the historiographical debates on the Baltic crusades, it addresses the paganism of the landscape in the written sources predating the crusades, in addition to the narrative, legal, and visual evidence of the crusade period (Chapter 1). -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

The Teutonic Order and the Baltic Crusades

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 6-10-2019 The eutT onic Order and the Baltic Crusades Alex Eidler Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Eidler, Alex, "The eT utonic Order and the Baltic Crusades" (2019). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 273. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/273 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The Teutonic Order and the Baltic Crusades By Alex Eidler Senior Seminar: Hst 499 Professor David Doellinger Western Oregon University June 5, 2019 Readers Professor Elizabeth Swedo Professor David Doellinger Copyright © Alex Eidler, 2019 Eidler 1 Introduction When people think of Crusades, they often think of the wars in the Holy Lands rather than regions inside of Europe, which many believe to have already been Christian. The Baltic Crusades began during the Second Crusade (1147-1149) but continued well into the fifteenth century. Unlike the crusades in the Holy Lands which were initiated to retake holy cities and pilgrimage sites, the Baltic crusades were implemented by the German archbishoprics of Bremen and Magdeburg to combat pagan tribes in the Baltic region which included Estonia, Prussia, Lithuania, and Latvia.1 The Teutonic Order, which arrived in the Baltic region in 1226, was successful in their smaller initial campaigns to combat raiders, as well as in their later crusades to conquer and convert pagan tribes. -

The Clash Between Pagans and Christians: the Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309

The Clash between Pagans and Christians: The Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309 Honors Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Donald R. Shumaker The Ohio State University May 2014 Project Advisor: Professor Heather J. Tanner, Department of History 1 The Baltic Crusades started during the Second Crusade (1147-1149), but continued into the fifteenth century. Unlike the crusades in the Holy Lands, the Baltic Crusades were implemented in order to combat the pagan tribes in the Baltic. These crusades were generally conducted by German and Danish nobles (with occasional assistance from Sweden) instead of contingents from England and France. Although the Baltic Crusades occurred in many different countries and over several centuries, they occurred as a result of common root causes. For the purpose of this study, I will be focusing on the northern crusades between 1147 and 1309. In 1309 the Teutonic Order, the monastic order that led these crusades, moved their headquarters from Venice, where the Order focused on reclaiming the Holy Lands, to Marienberg, which was on the frontier of the Baltic Crusades. This signified a change in the importance of the Baltic Crusades and the motivations of the crusaders. The Baltic Crusades became the main theater of the Teutonic Order and local crusaders, and many of the causes for going on a crusade changed at this time due to this new focus. Prior to the year 1310 the Baltic Crusades occurred for several reasons. A changing knightly ethos combined with heightened religious zeal and the evolution of institutional and ideological changes in just warfare and forced conversions were crucial in the development of the Baltic Crusades. -

|||GET||| Internal Colonization in Medieval Europe 1St Edition

INTERNAL COLONIZATION IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Felipe FernГѓВЎndez-Armesto | 9781351927024 | | | | | History of Germans in Poland German immigrants were also important in the rise of the cities and the establishment of the Polish burgher city-dwelling merchant class; they brought with them West European laws Magdeburg rights and customs which the Poles adopted. The Polish princes granted the Germans in the cities complete autonomy according to the " Teutonic right" later, " Magdeburg right "modeled on the laws of the cities of ancient Rome. Weimar Republic. An attempt is made As virtually all of the Western Baltic pagans became converted or exterminated the Prussian conquests were completed bythe Knights confronted Poland and Lithuaniathen the last pagan state in Europe. Even though the majority of the settlers were Germans Franks and Bavarians in the South, and Saxons and Flemings in the NorthWends and other tribes also participated in the settlement. Introducing Discourse Analysis: From Grammar to Society is a concise and accessible introduction by bestselling Both began to invite German settlers in order to develop their realm economically and to extend their rule. In the Middle Ages and today, it is the Romani—who consider themselves an ethnoracial group, despite Internal Colonization in Medieval Europe 1st edition internal heterogeneity among their peoples—who best personify the paradox of race and racial identification. Medieval Europe between 5th and 8th centuries, also referred to as the Dark Ages was marked by rise of numerous short-lived barbarian kingdoms and a period of general instability that delivered the final blow to long distance trade and manufacture for export as it was no longer safe to travel to any distance, especially after the Muslim conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries. -

Denmark and the Crusades 1400 – 1650

DENMARK AND THE CRUSADES 1400 – 1650 Janus Møller Jensen Ph.D.-thesis, University of Southern Denmark, 2005 Contents Preface ...............................................................................................................................v Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 Crusade Historiography in Denmark ..............................................................................2 The Golden Age.........................................................................................................4 New Trends ...............................................................................................................7 International Crusade Historiography...........................................................................11 Part I: Crusades at the Ends of the Earth, 1400-1523 .......................................................21 Chapter 1: Kalmar Union and the Crusade, 1397-1523.....................................................23 Denmark and the Crusade in the Fourteenth Century ..................................................23 Valdemar IV and the Crusade...................................................................................27 Crusades and Herrings .............................................................................................33 Crusades in Scandinavia 1400-1448 ..............................................................................37 Papal Collectors........................................................................................................38 -

A Comparison of the Medieval German Settlement of Prussia and Transylvania

Issue 4 2014 Sword, Cross, and Plow vs. Pickaxe and Coin: A Comparison of the Medieval German Settlement of Prussia and Transylvania GEORGE R. STEVENS CLEMSON UNIVERSITY The German medieval settlement of Eastern Europe known as the Ostsiedlung was carried out by Germans and the Teutonic Order in both Hungary and Transylvania, but with vastly different results. Of the regions settled during the Ostsiedlung, Transylvania offered colonists some of the strongest incentives to settle there; in addition to an agreeable climate and fertile soil, those who settled in Transylvania also stood to enjoy generous expansions of legal and economic freedoms far beyond the rights they held in their homelands. Yet the Ostsiedlung in Transylvania was arguably a failure compared to the success of the movement in Prussia. Much of this contrast can be explained by comparing the settlement process in each region, conducted largely by peaceful means in Transylvania but by the sword and cross in Prussia. Conquest and conversion supported by secular and ecclesiastical authorities allowed Germans to dominate Prussia and cement the primacy of German language and culture there. By contrast, peaceful settlement left Transylvania’s large indigenous populations intact and independent. This cultural plurality, along with the long journey required to reach Transylvania and inconsistent support for settlement there, ensured German settlers in Transylvania never became more than a minority population. The medieval settlement of Prussia and Transylvania, from here on referred to by its German name, Ostsiedlung, was carried out by Germans and the Teutonic Order in both regions, but to vastly different ends. The German settlement of Transylvania was mostly peaceful, with the majority of settlers being miners, merchants, and peasants. -

The Aristocracy of Leon-Castile in the Reign Of

THE ARISTOCRACY OF LEON-CASTILE IN THE REIGN OF ALFONSO VII (1126-1157) 2 VOLUMES ii SIMON FRASER BARTON DPhil UNIVERSITY, OF, YORK Department of History (April, 1990) TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME II Page Table of figures 376 CHAPTER 4 KING AND COURT 377 Introduction 378 (a) Alfonso VII and the Nobility 381 i) Grants 'pro bono seruiciol 384 ii) Honores and tenencias 387 iii) Money fiefs 398 (b) The Court of Alfonso VII 399 i) Court membership 401 ii) The business of the curia 422 iii) The royal household 433 iv) The peripatetic court 443 Notes to Chapter 4 457 CHAPTER 5: THE WARRIOR ARISTOCRACY 474 Introduction 475 (a) A society organised for war 476 -374- (b) The wars of the reign of Alfonso VII 482 (c) The logistics of warfare 500 i) The summons to war 501 ii) The composition of the army 502 iii) Numbers 510 iv) Naval power 512 V) Finance, supply and strategy 513 vi) Castles 520 (d) Motivation 528 (e) Risks and rewards 540 Notes to Chapter 5 550 CONCLUSION 563 APPENDIX 1: Selected aristocratic charters 566 APPENDIX 2: Genealogical tables 631 MANUSCRIPTS AND BOOKS CONSULTED 641 I. Manuscript sources II. Guides, catalogues and registers III. Printed Primary Sources IV. Secondary material -375- TABLE OF FIGURES PaRe_ Figure 5: Royal majordomos, 1126-1157 436 Figure 6: Royal alf4reces, 1126-1157 437 Figure 7 Lay confirmants to royal 492 diplomas of 1137 Figure 8 Lay confirmants to royal 493 diplomas of 1139 Figure 9 Lay confirmants to royal 494 diplomas of 1147 -376- CHAPTER 4 KING AND COURT -377- Introduction The relationship between king and nobleman in the Middle Ages was more often than not based upon mutual support and co-operation rather than upon mutual antagonism. -

181222 ICOMOS Heft LXVII Layout 1 11.01.19 09:12 Seite 1

181222_ICOMOS_Heft_LXVII_Cover_print_Layout 1 11.01.19 11:02 Seite 1 The Cultural Landscape of the Wendland Circular Villages Wendland Circular Villages Circular Wendland ICOMOS · HEFTE DES DEUTSCHEN NATIONALKOMITEES LXVII ICOMOS · JOURNALS OF THE GERMAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE LXVII ICOMOS · CAHIERS DU COMITÉ NATIONAL ALLEMAND LXVII ICOMOS · HEFTE DES DEUTSCHEN NATIONALKOMITEES LXVII ICOMOS · HEFTE DES DEUTSCHEN NATIONALKOMITEES 181222 ICOMOS Heft LXVII_Layout 1 11.01.19 09:12 Seite 1 INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON MONUMENTS AND SITES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SITES CONSEJO INTERNACIONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SITIOS МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫЙ СОВЕТ ПО ВОПРОСАМ ПАМЯТНИКОВ И ДОСТОПРИМЕЧАТЕЛЬНЫХ МЕСТ Conservation and Rehabilitation of Vernacular Heritage: The Cultural Landscape of the Wendland Circular Villages International conference and annual meeting of the ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Vernacular Architecture (CIAV) organised with ICOMOS Germany, the State Office for Monument Con- servation and Archaeology of Lower Saxony, and the Samtgemeinde of Lüchow-Wendland Lübeln, September 28 – October 2, 2016 Edited by Christoph Machat ICOMOS · HEFTE DES DEUTSCHEN NATIONALKOMITEES LXVII ICOMOS · JOURNALS OF THE GERMAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE LXVII ICOMOS · CAHIERS DU COMITÉ NATIONAL ALLEMAND LXVII 181222 ICOMOS Heft LXVII_print_Layout 1 15.02.19 12:21 Seite 2 Impressum ICOMOS Hefte des Deutschen Nationalkomitees Herausgegeben vom Nationalkomitee der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Präsident: Prof. Dr. Jörg Haspel Vizepräsident: Dr. Christoph Machat -

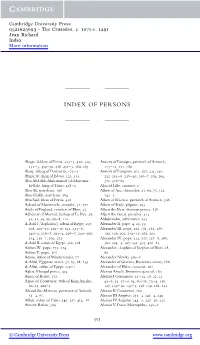

Index of Persons

Cambridge University Press 0521623693 - The Crusades, c. 1071-c. 1291 Jean Richard Index More information ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ INDEX OF PERSONS ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ Abaga, il-khan of Persia, 423±4, 426, 429, Aimery of Limoges, patriarch of Antioch, 432±3, 439±40, 446, 452±3, 460, 463 113±14, 171, 180 Abaq, atabeg of Damascus, 173±4 Aimery of Lusignan, 201, 207, 225, 230, Abgar, St, king of Edessa, 122, 155 232, 235±6, 238±40, 256±7, 264, 294, Abu Abdallah Muhammad (al-Mustansir 371, 376±80 bi-llah), king of Tunis, 428±9 Alan of Lille, canonist, 2 Abu Ali, merchant, 106 Albert of Aix, chronicler, 21, 69, 75, 123, Abu Ghalib, merchant, 384 142±3 Abu Said, khan of Persia, 456 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Antioch, 396 Achard of Montmerle, crusader, 31, 271 Albert of Stade, pilgrim, 293 Adela of England, countess of Blois, 35 Albert the Bear, German prince, 158 AdheÂmar of Monteil, bishop of Le Puy, 28, Albert the Great, preacher, 413 32, 42, 49, 60, 66±8, 112 Aldobrandin, adventurer, 254 al-Adil I (`Saphadin'), sultan of Egypt, 197, Alexander II, pope, 4, 23, 39 208, 209±10, 229±30, 232, 235±6, Alexander III, pope, 122, 181, 185, 188, 240±2, 256±7, 293±4, 296±7, 299±300, 190, 199, 202, 214±15, 260, 292 314, 350±1, 362, 375 Alexander IV, pope, 335, 337, 357±8, 360, al-Adil II, sultan of Egypt, 322, 328 362, 364±5, 367, 391, 397, 410±13 Adrian IV, pope, 175, 214 Alexander, chaplain of Stephen of Blois, 28, Adrian V, pope, 385 60 Adson, abbot of MontieÂrender, 17 Alexander Nevski, 360±1 al-Afdal, Egyptian vizier, 57, 65, 68, 139 Alexander of Gravina,