Downloaded from Brill.Com10/06/2021 07:10:31AM Via Free Access 146 Jasperse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aristocracy of Leon-Castile in the Reign Of

THE ARISTOCRACY OF LEON-CASTILE IN THE REIGN OF ALFONSO VII (1126-1157) 2 VOLUMES ii SIMON FRASER BARTON DPhil UNIVERSITY, OF, YORK Department of History (April, 1990) TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME II Page Table of figures 376 CHAPTER 4 KING AND COURT 377 Introduction 378 (a) Alfonso VII and the Nobility 381 i) Grants 'pro bono seruiciol 384 ii) Honores and tenencias 387 iii) Money fiefs 398 (b) The Court of Alfonso VII 399 i) Court membership 401 ii) The business of the curia 422 iii) The royal household 433 iv) The peripatetic court 443 Notes to Chapter 4 457 CHAPTER 5: THE WARRIOR ARISTOCRACY 474 Introduction 475 (a) A society organised for war 476 -374- (b) The wars of the reign of Alfonso VII 482 (c) The logistics of warfare 500 i) The summons to war 501 ii) The composition of the army 502 iii) Numbers 510 iv) Naval power 512 V) Finance, supply and strategy 513 vi) Castles 520 (d) Motivation 528 (e) Risks and rewards 540 Notes to Chapter 5 550 CONCLUSION 563 APPENDIX 1: Selected aristocratic charters 566 APPENDIX 2: Genealogical tables 631 MANUSCRIPTS AND BOOKS CONSULTED 641 I. Manuscript sources II. Guides, catalogues and registers III. Printed Primary Sources IV. Secondary material -375- TABLE OF FIGURES PaRe_ Figure 5: Royal majordomos, 1126-1157 436 Figure 6: Royal alf4reces, 1126-1157 437 Figure 7 Lay confirmants to royal 492 diplomas of 1137 Figure 8 Lay confirmants to royal 493 diplomas of 1139 Figure 9 Lay confirmants to royal 494 diplomas of 1147 -376- CHAPTER 4 KING AND COURT -377- Introduction The relationship between king and nobleman in the Middle Ages was more often than not based upon mutual support and co-operation rather than upon mutual antagonism. -

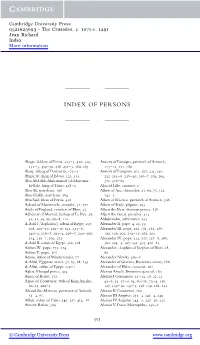

Index of Persons

Cambridge University Press 0521623693 - The Crusades, c. 1071-c. 1291 Jean Richard Index More information ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ INDEX OF PERSONS ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ Abaga, il-khan of Persia, 423±4, 426, 429, Aimery of Limoges, patriarch of Antioch, 432±3, 439±40, 446, 452±3, 460, 463 113±14, 171, 180 Abaq, atabeg of Damascus, 173±4 Aimery of Lusignan, 201, 207, 225, 230, Abgar, St, king of Edessa, 122, 155 232, 235±6, 238±40, 256±7, 264, 294, Abu Abdallah Muhammad (al-Mustansir 371, 376±80 bi-llah), king of Tunis, 428±9 Alan of Lille, canonist, 2 Abu Ali, merchant, 106 Albert of Aix, chronicler, 21, 69, 75, 123, Abu Ghalib, merchant, 384 142±3 Abu Said, khan of Persia, 456 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Antioch, 396 Achard of Montmerle, crusader, 31, 271 Albert of Stade, pilgrim, 293 Adela of England, countess of Blois, 35 Albert the Bear, German prince, 158 AdheÂmar of Monteil, bishop of Le Puy, 28, Albert the Great, preacher, 413 32, 42, 49, 60, 66±8, 112 Aldobrandin, adventurer, 254 al-Adil I (`Saphadin'), sultan of Egypt, 197, Alexander II, pope, 4, 23, 39 208, 209±10, 229±30, 232, 235±6, Alexander III, pope, 122, 181, 185, 188, 240±2, 256±7, 293±4, 296±7, 299±300, 190, 199, 202, 214±15, 260, 292 314, 350±1, 362, 375 Alexander IV, pope, 335, 337, 357±8, 360, al-Adil II, sultan of Egypt, 322, 328 362, 364±5, 367, 391, 397, 410±13 Adrian IV, pope, 175, 214 Alexander, chaplain of Stephen of Blois, 28, Adrian V, pope, 385 60 Adson, abbot of MontieÂrender, 17 Alexander Nevski, 360±1 al-Afdal, Egyptian vizier, 57, 65, 68, 139 Alexander of Gravina, -

Archbishop of Lund

INDEX Abodrites, see Slavs Alfonso VII, king of Castile (1126–57), Absalon, bishop of Roskilde (1158–92), 31–2, 35 archbishop of Lund (1177–1201), 47 Alfonso VIII, king of Castile Adalbert, archbishop of Hamburg- (1158–1214), 156–7 Bremen (1043–72), 29 Alfonso Henriques, king of Portugal Adalbert Vojt^ch, bishop of Prague (1139–85), 35 (983–97), 81 Alfonso Jordan, count of Toulouse Adam of Bremen, chronicler (d. before (d. 1148), 35 1085), 13, 29 Almeria, 35–6 Adolf, count of Holstein (d. 1164), 35 Alvis, bishop of Arras (1134–47), 34 Adrian IV, pope (1154–9), 34, 51 Amadeus III, count of Savoy Alberic of Trois-Fontaines, chronicler (1103–48), 34–5 (d. after 1251), 175 Anastasius IV, pope (1153–4), 63–4 Albert (Suerbeer), archbishop of Riga Anders (Sunesen), archbishop of Lund (1253/55–1273), 230–1, 233, 243 (1201–22) Albert (of Buxhövden), bishop of and crusades to the Holy Land, Livonia (1199–1229), 80, 187 87–8, 101 n. 82 and the Danes, 133–4 and the curia, 85–6, 88–9, 152, and the ecclesiastical organization, 157, 160 n. 112, 250 123, 125–6, 171, 181–2 and Estonia, 85, 123–4, 157 and Emperor Frederick II, 203–4 and Finland, 82–3, 126 and Henry of Livonia, 14 and mission, 82–3, 86 and the new converts, 117–19 legatine powers of, 126–7 and the Sword-Brothers, 80–1, 134 Andrew II, king of Hungary (1205–35), and William of Modena, see William, 158–9, 189 n. 10 bishop of Modena Anselm, bishop of Havelberg (d. -

Read Transcript

History of the Crusades. Episode 36. The Second Crusade VIII. Hello again. Last week we saw the Crusaders arrive in the Holy Land. King Louis and the remaining French Knights arrived in Antioch, while King Conrad sailed in from Constantinople, where he had been recuperating from an arrow wound to his head which he suffered in Anatolia. The southern French fleets, complete with fresh men, arrived in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, as did the ships containing the Latin Christians who had taken Lisbon in Portugal. At the conclusion of last week's episode, we learned that a decision had been made for the Crusaders to attack Damascus. We'll come to that decision in a minute. But first I have a sad tale to tell you all. Remember Alfonso Jordan, Count of Toulouse? He's the son of Raymond, Count of Toulouse, founder of the Crusader state of Tripoli. Alfonso Jordan fled Tripoli as a baby after the death of his father, and went on to become Count of the wealthy region of Toulouse in France. Toulouse borders the Mediterranean Sea on the southern coast of France, and Alfonso Jordan and his contingent of knights very sensibly decided to sail to the Holy Land. Alfonso Jordan sailed into Acre in April 1148. His arrival was heralded by the Christian citizens of the County of Tripoli, who were eager to welcome back into the fold the son of their founder, who had, after all, been born in the region. But there were people who were not so keen to welcome Alfonso Jordan, and they of course, were the current Count of Tripoli, Raymond and his wife, the Countess Hodierna. -

History of the Crusades. Episode 32. the Second Crusade IV. Hello

History of the Crusades. Episode 32. The Second Crusade IV. Hello again. Last week we saw Pope Eugenius issue a Papal Bull calling for a Crusade, and we followed Bernard of Clairvaux as he embarked on a massive and successful recruitment drive for the Crusade. There are now tens of thousands of citizens across Europe, mainly from France and Germany, preparing to set out for the Middle East. Now, before we join the participants of the Second Crusade as they prepare for their expedition, there are events happening in other parts of Europe that we need to take a brief look at. Crusading zeal had taken a firm hold in Europe, and while the main arena was always going to be the Holy Land, the Second Crusade ended up manifesting itself on two fronts within Europe itself. The most significant of these occurred on the Spanish peninsula. In the spring of 1147, a fleet of ships containing Crusaders from England and northern Europe set sail for the Holy Land. They didn't end up in the Middle East, though. Instead they found themselves landing on the Portuguese coast. Now, historians have debated for many years whether this was intentional or whether the ships were driven to seek shelter in Portugal due to bad weather. On one side of the debate, the ships were leaving for the Holy Land prior to the main field of Crusaders who were going to walk to the Middle East. Clearly, the ships were going to arrive at their destination much earlier than the rest of the Crusaders, and there seems no reason for them to do this and then spend months hanging around waiting for everyone else to show up, so some historians argue that perhaps the Church had requested the sailors to call into Portugal on their way to the Holy Land. -

The Crusades and the Kingdom of Jerusalem

Onward Christian Soldiers 1 Onward Christian Soldiers The Crusades and The Kingdom of Jerusalem Rules for The Second Crusade; 1148 & The Third Crusade; 1191-1192 a Richard H. Berg Game Design Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................ 2 9. Naval Rules ................................................................ 20 2. Components ............................................................... 2 10. Resources and Communication ................................. 22 3. General Course of Play .............................................. 4 11. Neutrals and Assassins ............................................... 22 4. The Activation Markers (2C/3C only) ....................... 5 12. Events ......................................................................... 23 5. Leaders and Manpower .............................................. 5 Scenario 1: The Second Crusade ....................................... 24 6. Land Movement, Continuation, and Attrition ............ 7 Scenario 2: The Third Crusade (Historical) ...................... 26 7. Land Combat.............................................................. 10 The Third Crusade: Barbarossa (What if?) ....................... 29 8. Towns, Cities, and Castles ......................................... 15 Counterscan (sheet 3) ........................................................ 31 GMT Games, LLC P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com © 2006 GMT Games, LLC 2 Onward Christian Soldiers The Towns and Cities are all -

The Cathars. Dualist Heretics in Languedoc in the High Middle Ages

-l :r:: m n -l> >:r:: 7' Vl THE MEDIEVAL WORLD Editor: David Bates John Moorlltad Ambrose John Moorhead Justinian JaILel Nelson Charles the Bald Paul Fouracre The Age of Charles Martel Richard Abels Alfred the Great M. K Lawson Cnut H. R. Lo)/Tt The English Church, 940- 1 154 Malcolm &rber The Cathars Janw A. Bnmdage Medieval Canon Law John Hudson The Formation of the English Common Law lindy Grant Abbot Suger of St-Denis David Crouch William Marshal Ralph V TuT7ltT The Reign of Richard Lionheart Ralph V Turner King John Jim Bradbury Philip Augustus Jane SaytrS Innocent m c. H. Lowrmu The Friars David Abultifia The Western Mediterranean Kingdoms 1200- 1500 Jean Dunbabin Charles I of Anjou Jennifer C. Ward English Noblewomen in the Later Middle Ages Michael Hicks Bastard Feudalism THE CATHARS Dualist Heretics in Languedoc in the High Middle Ages MALCOLM BARBER First published 2000 by Pearson Education Limited Published 2014 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint ofthe Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © Pearson Education Limited 2000 The right of Malcolm Barber to be identified as author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the Publishers or a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WIT 4LP. -

PDF Printing 600

REVUE BELGE DE NUMISMATIQUE ET DE SIGILLOGRAPHIE BELGISCH TIJDSCHRIFT VOOR NUMISMATIEK EN ZEGELKUNDE PUBLIÉE UITGEGEVEN SOUS LE HAUT PATRONAGE ONDER DE HOGE BESCHERMING DE S. M. LE ROI VAN Z. M. DE KONING PAR LA DOOR HET soc IÉTE: ROY ALE KONINKLIJK BELGISCH DE NUMISMATIQUE DE BELGIQUE GENOOTSCHAP VOOR NUMISMATIEK AVEC L'AIDE DE LA DIRECTION GÉNÉRALE DE MET DE FINANCIËLE HULP VAN HET L'ENSEIGNEMENT, DE LA FORMATION ET DE MINISTERIE VAN DE VLAAMSE GEMEENSCHAP LA RECHERCHE DU MINISTÈRE DE LA EN VAN DE DIRECTION GÉNÉRALE DE COMMUNAUTÉ FRANÇAISE ET DU L'ENSEIGNEMENT, DE LA FORMATION ET MINISTERIE DE LA RECHERCHE DU MINISTÈRE VAN DE VLAAMSE GEMEENSCHAP DE LA COMMUNAUTË FRANÇAISE DIRECTEURS: PAUL NASTER, TONY HACKENS, MAURICE COLAERT, PATRICK MARCHETTI CXXXIV -1988 BRUXELLES BRUSSEL PAUL BEDOUKIAN COINAGE OF TRIPOLI (XIlth.XIIrh CENTURY) In studying the coinage of Tripoli, one is faced with a number of problems in making attibutions. Since eight rulers - four Ray monds and four Bohemonds - struck several types of coins over a span of 150 years, the numismatist is faced with a puzzle that seems to defy solution. De Saulcy (1847), Schlumberger (1878), Sabine (1980) and Metcalf (1983) wrote extensively on the eoinage, but made attributions with many reservations. In researching the coinage of Tripoli, the writer tried to bring together evidence available in 16 mixed erusader hoards (1), histori cal sequences (2) and numismatic data (3). It was felt that if aIl three supported one theory or attribution, then this theory ean he considered acceptable until new findings be they hoard, historical or nurnisrnatic - advance a different pre mise. -

Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse - Wikipedia

3/18/2021 Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse - Wikipedia [ Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse, Raymond of Saint-Giles. (Accessed Mar. 18, 2021. Wikipedia. ] Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse Raymond IV (c. 1041[1] – 28 February 1105), sometimes called Raymond IV Raymond of Saint-Gilles or Raymond I of Tripoli, was a powerful noble in southern France and one of the leaders of the First Crusade (1096–99). He was the Count of Toulouse, Duke of Narbonne and Margrave of Provence from 1094, and he spent the last five years of his life establishing the County of Tripoli in the Near East. Contents Sketch of Raymond's seal Count of Tripoli Early years Reign 1102 – 1105 The First Crusade Successor Alfonso Jordan Extending his territorial reach Count of Toulouse Crusade of 1101, siege of Tripoli, and death Reign 1094 – 1105 Spouses and progeny Predecessor William IV References Successor Bertrand Sources Born c. 1041 Died 28 February 1105 Early years (aged 63–64) Citadel of Raymond Raymond was a son of Pons of Toulouse and Almodis de La Marche.[2] He de Saint-Gilles, received Saint-Gilles with the title of "count" from his father and displaced Tripoli his niece Philippa, Duchess of Aquitaine, his brother William IV's Spouse Daughter of Godfrey daughter, in 1094 from inheriting Toulouse. In 1094, William Bertrand of I of Arles Provence died and his margravial title to Provence passed to Raymond. A Matilda of Sicily bull of Urban's dated 22 July 1096 names Raymond comes Nimirum Elvira of Castile Tholosanorum ac Ruthenensium et marchio Provintie Raimundus ("Raymond, count of Nîmes, Toulouse and Rouergue and margrave of Issue Bertrand Provence"). -

The Aristocracy of Leon-Castile in the Reign Of

THE ARISTOCRACY OF LEON-CASTILE IN THE REIGN OF ALFONSO VII (1126-1157) 2 VOLUMES SIMON FRASER BARTON DPhil UNIVERSITY OF YORK Department of History (April, 1990) TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I Paize Table of figures 6 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract Abbreviations INTRODUCTION 13 Notes to Introduction 27 CHAPTER 1 : CLASS9 FAMILY AND LINEAGE 30 (a) The a rticulation of a class 31 (b) Famil y 57 i) Kinship and Inheritance 58 ii) Lineage 71 iii) Birth and Childhood 82 iv) Marriage 88 V) Old age and Death 108 (c) Noble households 112 i) Household organisation 112 ii) Residence 129 - iii) Recreation and Culture 132 Notes to Chapter 1 138 CHAPTER 2: PROPERTYAND POWER 164 Introduction 165 (a) The aristocratic patrimony 171 i) Rural property 173 ii) Urban property 191 iii) Great landowners 196 iv) Other sources of wealth 201 (b) The Lord and his Manor 206 i) Immune lordships 208 ii) The evidence of the fueros 211 iii) The structure of the Manor 215 iv) The profits of lordship 220 V) Administration 227 (c) Magnates and Milites 235 Notes to Chapter 2 243 CHAPTER 3 : THE NOBILITY AND THE CHURCH 258 Introduction 259 (a) The Adelskirche, in Le6n-Castile 263 i) The Proprietary Church 263 ii) Careers in the Church 275 (b) Lay aristocratic piety in Le6n-Castile 280 - i) The foundation of monasteries 280 ii) Endowment of the Church 315 iii) Pilgrimage and Crusade 329 (c) Conflict with the Church 334 Epilogue 354 Notes to Chapter 3 357 VOLUME II Table of contents 374 Table of figures 376 CHAPTER 4 KING AND COURT 377 Introduction 378 (a) Alfonso VII and the Nobility -

Coins of the CRUSADERS

Coins of the CRUSADERS The Crusades were a series of military conflicts of a religious character waged by much of Christian Europe against external and internal threats. Crusades were fought against Muslims, pagan Slavs, Russian and Greek Orthodox Christians, Mongols, Cathars, Hussites, and political enemies of the popes.[1] Crusaders took vows and were granted an indulgence for past sins. The Crusades originally had the goal of recapturing Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim rule and were original- ly launched in response to a call from the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine Empire for help against the expansion of the Muslim Seljuk Turks into Anatolia. The term is also used to describe contemporaneous and subsequent campaigns conducted through to the 16th century in territories outside the Levant usually against pagans, heretics, and peoples under the ban of excommunication for a mixture of religious, economic, and political reasons. Rivalries among both Christian and Muslim powers led also to alliances between religious factions against their opponents, such as the Christian alliance with the Sultanate of Rum during the Fifth Crusade. The Crusades had far-reaching political, economic, and social impacts, some of which have lasted into contemporary times. Because of internal conflicts among Christian kingdoms and political powers, some of the crusade expeditions were diverted from their original aim, such as the Fourth Crusade, which resulted in the sack of Christian Constantinople and the partition of the Byzantine Empire between Venice and the Crusaders. The Sixth Crusade was the first crusade to set sail without the official blessing of the Pope, establishing the precedent that rulers other than the Pope could initiate a crusade. -

Cathars: the Most Successful Heresy of the Middle Ages

00Cathars 1-172 29/11/05 1:58 pm Page 3 The Cathars SEAN MARTIN POCKET ESSENTIALS 00Cathars 1-172 29/11/05 1:58 pm Page 2 Other books in this series by the same author The Black Death Alchemy and Alchemists The Knights Templar 00Cathars 1-172 29/11/05 1:58 pm Page 1 The Cathars www.pocketessentials.com 00Cathars 1-172 29/11/05 1:58 pm Page 4 First published in 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ www.pocketessentials.com © Sean Martin 2005 The right of Sean Martin to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.The book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form or binding cover other than in which it is published, and without similar conditions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 10: 1 904048 33 1 ISBN 13: 978 1 904048 33 6 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPD Ltd, Ebbw Vale,Wales 00Cathars 1-172 29/11/05 1:58 pm Page 5 For all the Good Christians, past and present and In Memory of My Father, whose feet tread the lost aeons 00Cathars 1-172 29/11/05 1:58 pm Page 6 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Ion Mills, for bearing with me during the writing of this book; my sister Lois, for her advice; Nick Harding, for the usual lending of tomes and cama- raderie; and fellow credente Adso Brown.