PDF Printing 600

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love and War: Troubadour Songs As Propaganda, Protest, and Politics in the Albigensian Crusade

Love and War: Troubadour Songs as Propaganda, Protest, and Politics in the Albigensian Crusade By Leslee Wood B.A., University of Utah, 2003 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music. _________________________________________ Chair: Roberta Schwartz, PhD _________________________________________ Paul Laird, PhD _________________________________________ Bryan Kip Haaheim, DMA Date Defended: May 25, 2017 The thesis committee for Leslee Wood certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Love and War: Troubadour Songs as Propaganda, Protest, and Politics in the Albigensian Crusade ___________________________________________ Chair: Roberta Schwartz, PhD Date approved: May 25, 2017 ii Abstract: From the eleventh through the thirteenth century, the troubadours flourished in the Occitan courts of southern France. As the artistic and political voices of their culture, these men and women were educated, creative, and well-placed to envoice the cultural and political events of their time. In 1208, Pope Innocent III launched the Albigensian Crusade against the pervasive Cathar sect, which had attracted followers from every stratum of Occitan society, including believers from the most important ruling families. For twenty years, the crusade decimated the region and destroyed the socio-political apparatus which had long supported, and been given voice by, the troubadours and trobairises. By the end of the war in 1229, the Occitan nobility were largely disinherited and disempowered, unable to support the kind of courtly estates to which they had been accustomed and in which the art de trobar had flourished. Many troubadours were involved both politically and militarily in the crusade and their lyric reactions include astute political commentaries, vigorous calls-to-arms, invectives against the corruption of the Catholic clergy and the French invaders, and laments for the loss of both individuals and institutions. -

Cathar Or Catholic: Treading the Line Between Popular Piety and Heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271

Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of History William Kapelle, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master’s Degree by Elizabeth Jensen May 2013 Copyright by Elizabeth Jensen © 2013 ABSTRACT Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. A thesis presented to the Department of History Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Elizabeth Jensen The Occitanian Cathars were among the most successful heretics in medieval Europe. In order to combat this heresy the Catholic Church ordered preaching campaigns, passed ecclesiastic legislation, called for a crusade and eventually turned to the new mechanism of the Inquisition. Understanding why the Cathars were so popular in Occitania and why the defeat of this heresy required so many different mechanisms entails exploring the development of Occitanian culture and the wider world of religious reform and enthusiasm. This paper will explain the origins of popular piety and religious reform in medieval Europe before focusing in on two specific movements, the Patarenes and Henry of Lausanne, the first of which became an acceptable form of reform while the other remained a heretic. This will lead to a specific description of the situation in Occitania and the attempts to eradicate the Cathars with special attention focused on the way in which Occitanian culture fostered the growth of Catharism. In short, Catharism filled the need that existed in the people of Occitania for a reformed religious experience. -

About Fanjeaux, France Perched on the Crest of a Hill in Southwestern

About Fanjeaux, France Perched on the crest of a hill in Southwestern France, Fanjeaux is a peaceful agricultural community that traces its origins back to the Romans. According to local legend, a Roman temple to Jupiter was located where the parish church now stands. Thus the name of the town proudly reflects its Roman heritage– Fanum (temple) Jovis (Jupiter). It is hard to imagine that this sleepy little town with only 900 inhabitants was a busy commercial and social center of 3,000 people during the time of Saint Dominic. When he arrived on foot with the Bishop of Osma in 1206, Fanjeaux’s narrow streets must have been filled with peddlers, pilgrims, farmers and even soldiers. The women would gather to wash their clothes on the stones at the edge of a spring where a washing place still stands today. The church we see today had not yet been built. According to the inscription on a stone on the south facing outer wall, the church was constructed between 1278 and 1281, after Saint Dominic’s death. You should take a walk to see the church after dark when its octagonal bell tower and stone spire, crowned with an orb, are illuminated by warm orange lights. This thick-walled, rectangular stone church is an example of the local Romanesque style and has an early Gothic front portal or door (the rounded Romanesque arch is slightly pointed at the top). The interior of the church was modernized in the 18th century and is Baroque in style, but the church still houses unusual reliquaries and statues from the 13th through 16th centuries. -

Capuchins As Crusaders: Southern Gaul Ill the Late Twelfth Century

77 Capuchins as Crusaders: Southern Gaul ill the late Twelfth Century John France Swansea UniversIty The Peace and Truce of God has attracted much attention, both as something of importance in itself and because many have thought it played an important role in preparing men's minds for the appeal made at Clermont in 1095. Thi~ was finnly endorsed by Erdmann, Delaruelle and Duby, to name simply the most imporum~ and through them it passed into the common currency of crusader writing. l The only writer to have contested this view is Marcus Bull, who sharply doubts the impact of this movement on the anns-bearing laity by the end of the 11111 century. i This article is not concerned with its impact on the First Crusade, but on its continuance in southern Gaul in the twelfth century and the way in which the Capuchin movement, for all its apparent affinity with the Peace Movement, actually drew its inspiration and fonn from something quite different, the crusading movement This has not been recognised because the Capuchin movement was distorted by some medieval writers whose attitudes have powerfully influenced modem historians. The Capuchins were an armed fraternity which attempted to end the terrible disorders in central and southern Gaul caused by mercenary bands whose depredations reached a climax at this time. A vision of the Virgin, granted to a carpenter of I.e Puy in 1182, was said to have been inspired a wave of popular enthusiasm, as a result of which they enjoyed considerable success. They were called Capuchins (capuciaa) because they wore a distinctive hood and cloak bearing a badge of the Virgin and Child. -

In Her Voice: the Destruction of the Cathars in Languedoc

IN HER VOICE: THE DESTRUCTION OF THE CATHARS IN LANGUEDOC A Thesis by Diana Jane Morton Bachelors of Science, Montana State University, 1978 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Studies and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2009 © Copyright 2009 by Diana Jane Morton All Rights Reserved Note that thesis and dissertation work is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. Only the author has the legal right to publish, produce, sell, or distribute this work. Author permission is needed for others to directly quote significant amounts of information in their own work or to summarize substantial amounts of information in their own work. Limited amounts of information cited, paraphrased, or summarized from the work may be used with proper citation of where to find the original work. IN HER VOICE: THE DESTRUCTION OF THE CATHARS IN LANGUEDOC The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for the form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies. ______________________________________ Anthony Gythiel, Committee Chair ______________________________________ Deborah Gordon, Committee Member ______________________________________ William Woods, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my beloved parents, Warren and Gwendolyn Stumm iv ―Fiction and non-fiction are only different techniques of story-telling.‖ --Arundhati Roy v ABSTRACT The following thesis is a narrative history of the persecution and ultimate elimination of a Christian heresy called Catharism. Their destruction was brought about by the Roman Catholic Church which saw the Cathar‘s strength in numbers, wealth, and organization as a viable threat to its power. -

Lorraine Simonis

The Kingdom, the Power and the Glory: the Albigensian Crusade and the Subjugation of the Languedoc A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Bachelor of Arts Degree with Honors in Medieval and Renaissance Studies Lorraine Marie Alice Simonis Washington and Lee University April 11, 2014 David Peterson, Advisor Alexandra Brown, Second Reader 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Notes 5 Timeline 7 Illustrations 9 Introduction 12 Chapter 1: “The Little Foxes Spoiling the Vineyard of the Lord” 17 Religious Dissent The Medieval Church and Heresy Cathar History and Cosmology Chapter 2: “The Practical Consequences of Catharism” 30 The Uniqueness of the Cathars Cathars and Clerics The Popular Appeal of Catharism Chapter 3: “The Chief Source of the Poison of Faithlessness” 39 The Many Faces of “Feudalism” Chivalric Society vs. Courtly Society The Political Structure of the South The Southern Church Chapter 4: “The Business of the Peace and of the Faith” 54 The Conspicuous Absence of the Albigensians A Close Reading of the Statutes of Pamiers and the Charter of Arles Pamiers Arles Conclusion 66 3 Bibliography 72 Primary Sources Secondary Sources 4 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I’d like to thank my readers, Profs. Peterson and Brown, for all of their guidance and support – not only in writing this thesis, but throughout my time at Washington & Lee. If it weren’t for Prof. Peterson, who introduced me to the Medieval & Renaissance Studies program while I was still a prospective student, I may never have developed an interest in this topic in the first place. Thanks also to all the professors who’ve made my time here at Washington & Lee so special and successful, especially Profs. -

History of the Crusades. Episode 113. the Crusade Against the Cathars

History of the Crusades. Episode 113. The Crusade Against The Cathars. Count Raymond VI of Toulouse. Hello again. Last week we saw the religion of the Cathars expand across Languedoc, despite efforts by the Catholic Church and Count Raymond V of Toulouse to suppress the heresy. In the year 1194 the political landscape of southern France shifted. In that year Raymond V of Toulouse died, and his son Raymond VI became Count of Toulouse. Raymond VI was 38 years old when he became Count, and his rule was markedly different to that of his father. Where Raymond V had been willing to bend to the authority of the Pope, Raymond VI was more liberal and tolerant in his acceptance of other religions. Whereas Raymond V, who had been married to the sister of the King of France, felt allied to the King of France, Raymond VI didn't feel those ties as strongly. In fact, Raymond VI was altogether quite a different man from his father. He had been raised in the wealthy surrounds of the noble house of Toulouse, and until he became Count at the age of 38 he really didn't have to do anything, other than sit back, enjoy life, and watch on with amusement as his father ducked and weaved around the political minefield that was France in the late twelfth century. Understandably, he developed a taste for luxury, for women, and for high living. Surprisingly, though, he didn't seem at all keen to engage in warfare. His sole military experience when he became Count was his engagement in a few minor military skirmishes. -

The Aristocracy of Leon-Castile in the Reign Of

THE ARISTOCRACY OF LEON-CASTILE IN THE REIGN OF ALFONSO VII (1126-1157) 2 VOLUMES ii SIMON FRASER BARTON DPhil UNIVERSITY, OF, YORK Department of History (April, 1990) TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME II Page Table of figures 376 CHAPTER 4 KING AND COURT 377 Introduction 378 (a) Alfonso VII and the Nobility 381 i) Grants 'pro bono seruiciol 384 ii) Honores and tenencias 387 iii) Money fiefs 398 (b) The Court of Alfonso VII 399 i) Court membership 401 ii) The business of the curia 422 iii) The royal household 433 iv) The peripatetic court 443 Notes to Chapter 4 457 CHAPTER 5: THE WARRIOR ARISTOCRACY 474 Introduction 475 (a) A society organised for war 476 -374- (b) The wars of the reign of Alfonso VII 482 (c) The logistics of warfare 500 i) The summons to war 501 ii) The composition of the army 502 iii) Numbers 510 iv) Naval power 512 V) Finance, supply and strategy 513 vi) Castles 520 (d) Motivation 528 (e) Risks and rewards 540 Notes to Chapter 5 550 CONCLUSION 563 APPENDIX 1: Selected aristocratic charters 566 APPENDIX 2: Genealogical tables 631 MANUSCRIPTS AND BOOKS CONSULTED 641 I. Manuscript sources II. Guides, catalogues and registers III. Printed Primary Sources IV. Secondary material -375- TABLE OF FIGURES PaRe_ Figure 5: Royal majordomos, 1126-1157 436 Figure 6: Royal alf4reces, 1126-1157 437 Figure 7 Lay confirmants to royal 492 diplomas of 1137 Figure 8 Lay confirmants to royal 493 diplomas of 1139 Figure 9 Lay confirmants to royal 494 diplomas of 1147 -376- CHAPTER 4 KING AND COURT -377- Introduction The relationship between king and nobleman in the Middle Ages was more often than not based upon mutual support and co-operation rather than upon mutual antagonism. -

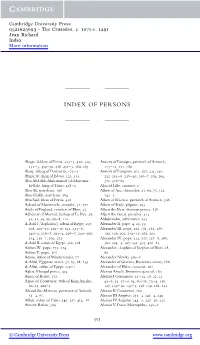

Index of Persons

Cambridge University Press 0521623693 - The Crusades, c. 1071-c. 1291 Jean Richard Index More information ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ INDEX OF PERSONS ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ Abaga, il-khan of Persia, 423±4, 426, 429, Aimery of Limoges, patriarch of Antioch, 432±3, 439±40, 446, 452±3, 460, 463 113±14, 171, 180 Abaq, atabeg of Damascus, 173±4 Aimery of Lusignan, 201, 207, 225, 230, Abgar, St, king of Edessa, 122, 155 232, 235±6, 238±40, 256±7, 264, 294, Abu Abdallah Muhammad (al-Mustansir 371, 376±80 bi-llah), king of Tunis, 428±9 Alan of Lille, canonist, 2 Abu Ali, merchant, 106 Albert of Aix, chronicler, 21, 69, 75, 123, Abu Ghalib, merchant, 384 142±3 Abu Said, khan of Persia, 456 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Antioch, 396 Achard of Montmerle, crusader, 31, 271 Albert of Stade, pilgrim, 293 Adela of England, countess of Blois, 35 Albert the Bear, German prince, 158 AdheÂmar of Monteil, bishop of Le Puy, 28, Albert the Great, preacher, 413 32, 42, 49, 60, 66±8, 112 Aldobrandin, adventurer, 254 al-Adil I (`Saphadin'), sultan of Egypt, 197, Alexander II, pope, 4, 23, 39 208, 209±10, 229±30, 232, 235±6, Alexander III, pope, 122, 181, 185, 188, 240±2, 256±7, 293±4, 296±7, 299±300, 190, 199, 202, 214±15, 260, 292 314, 350±1, 362, 375 Alexander IV, pope, 335, 337, 357±8, 360, al-Adil II, sultan of Egypt, 322, 328 362, 364±5, 367, 391, 397, 410±13 Adrian IV, pope, 175, 214 Alexander, chaplain of Stephen of Blois, 28, Adrian V, pope, 385 60 Adson, abbot of MontieÂrender, 17 Alexander Nevski, 360±1 al-Afdal, Egyptian vizier, 57, 65, 68, 139 Alexander of Gravina, -

Archbishop of Lund

INDEX Abodrites, see Slavs Alfonso VII, king of Castile (1126–57), Absalon, bishop of Roskilde (1158–92), 31–2, 35 archbishop of Lund (1177–1201), 47 Alfonso VIII, king of Castile Adalbert, archbishop of Hamburg- (1158–1214), 156–7 Bremen (1043–72), 29 Alfonso Henriques, king of Portugal Adalbert Vojt^ch, bishop of Prague (1139–85), 35 (983–97), 81 Alfonso Jordan, count of Toulouse Adam of Bremen, chronicler (d. before (d. 1148), 35 1085), 13, 29 Almeria, 35–6 Adolf, count of Holstein (d. 1164), 35 Alvis, bishop of Arras (1134–47), 34 Adrian IV, pope (1154–9), 34, 51 Amadeus III, count of Savoy Alberic of Trois-Fontaines, chronicler (1103–48), 34–5 (d. after 1251), 175 Anastasius IV, pope (1153–4), 63–4 Albert (Suerbeer), archbishop of Riga Anders (Sunesen), archbishop of Lund (1253/55–1273), 230–1, 233, 243 (1201–22) Albert (of Buxhövden), bishop of and crusades to the Holy Land, Livonia (1199–1229), 80, 187 87–8, 101 n. 82 and the Danes, 133–4 and the curia, 85–6, 88–9, 152, and the ecclesiastical organization, 157, 160 n. 112, 250 123, 125–6, 171, 181–2 and Estonia, 85, 123–4, 157 and Emperor Frederick II, 203–4 and Finland, 82–3, 126 and Henry of Livonia, 14 and mission, 82–3, 86 and the new converts, 117–19 legatine powers of, 126–7 and the Sword-Brothers, 80–1, 134 Andrew II, king of Hungary (1205–35), and William of Modena, see William, 158–9, 189 n. 10 bishop of Modena Anselm, bishop of Havelberg (d. -

Read Transcript

History of the Crusades. Episode 36. The Second Crusade VIII. Hello again. Last week we saw the Crusaders arrive in the Holy Land. King Louis and the remaining French Knights arrived in Antioch, while King Conrad sailed in from Constantinople, where he had been recuperating from an arrow wound to his head which he suffered in Anatolia. The southern French fleets, complete with fresh men, arrived in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, as did the ships containing the Latin Christians who had taken Lisbon in Portugal. At the conclusion of last week's episode, we learned that a decision had been made for the Crusaders to attack Damascus. We'll come to that decision in a minute. But first I have a sad tale to tell you all. Remember Alfonso Jordan, Count of Toulouse? He's the son of Raymond, Count of Toulouse, founder of the Crusader state of Tripoli. Alfonso Jordan fled Tripoli as a baby after the death of his father, and went on to become Count of the wealthy region of Toulouse in France. Toulouse borders the Mediterranean Sea on the southern coast of France, and Alfonso Jordan and his contingent of knights very sensibly decided to sail to the Holy Land. Alfonso Jordan sailed into Acre in April 1148. His arrival was heralded by the Christian citizens of the County of Tripoli, who were eager to welcome back into the fold the son of their founder, who had, after all, been born in the region. But there were people who were not so keen to welcome Alfonso Jordan, and they of course, were the current Count of Tripoli, Raymond and his wife, the Countess Hodierna. -

How Successful Was the Albigensian Crusade for the Kings of France and the Popes?

1800944 How successful was the Albigensian Crusade for the Kings of France and the Popes? A Crusade is a war carried out under Papal sanction; the Albigensian Crusade was a crusade against the Cathars, and their protectors in the Languedoc region in the South of France. The Cathars were a highly organised religious group who had a clear hierarchy, that included Bishops, Deacons, and Perfecti, that gave spiritual guidance to the group’s followers. The Cathars had alternative views to Catholicism, with Gnosticism and dualism beliefs at their religious core. Catharism had come to southern France from the Bogomils in Bulgaria and was allowed to grow in Southern France due to the tolerance from local Lords in the region. These local Lords such as, Rouergue and the Trencavel, also protected the Cathars from persecution from leaders of the Crusade such as Simon de Montfort. The Albigensian Crusade was a very stop-start conflict, with different powers taking control of the region, and the Crusade at various points. The first Albigensian Crusade was approximately from 1209 to 1225 and was guided by the Papacy. The Papacy’s reason for calling the Crusade in 1209, was to crush the Cathar heresy, and to strengthen Catholicism in the area, after Papal legate Peter de Castelnau was murdered in Toulouse, a clear sign of a lack of Catholicism’s strength in the area. After the deaths of Innocent III in 1216, and Simon de Montfort in 1218 the Crusade was hijacked by the Kings of France, and thus beginning the second Albigensian Crusade; which lasted from 1225-1229, ending with the Treaty of Paris.