Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Najaarsconcert 2018 2

NAJAARSCONCERT 2018 2 Welkom Beste concertbezoeker, Ik heet u namens de Oratoriumvereniging van harte welkom bij ons najaarsconcert in deze prachtige Martinikerk van Bolsward. Dit concert staat in het teken van Jacob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (geboren 3 februari 1809 en overleden op 4 november 1847). Hij was een Duitse componist, pianist, organist en dirigent in de vroeg romantische periode. Mendelssohn schreef symfonieën, concerten, oratoria, pianomuziek en kamermuziek. Hij vierde zijn successen in Duitsland en liet de muziek van Johann Sebastian Bach herleven. Vanmiddag voeren wij twee werken van hem uit: het Lobgesang en Psalm 42. Verder zal onze organist nog een sonate van Mendelssohn spelen. Onze uitvoering vanmiddag is een bijzondere uitvoering. Zoals u ziet zijn het koor, het orkest en de solisten geplaatst op een speciaal voor deze uitvoering gemaakt podium vlak voor het prachtige kerkorgel, dat meewerkt aan de uitvoering. U, als publiek zit nu ook andersom. Wij willen vandaag als koor ervaren hoe deze opstelling bevalt. Mocht dat positief zijn, dan zullen we in de toekomst waarschijnlijk vaker gebruik gaan maken van deze opstelling. In dit concertboekje kunt u verder alle informatie over dit concert lezen. Ook is er een plattegrond opgenomen waarop staat aangegeven waar de toiletten zijn en waar de nooduitgangen zich bevinden. Graag deze plattegrond voor aanvang van het concert goed bekijken. Volgend jaar voeren wij in de week voor Pasen weer tweemaal de Matthäus-Passion uit en in het najaar de volledige uitvoering van de Messiah van Händel. We hopen u dan ook als luisteraar te mogen begroeten. Met vriendelijke groeten, G.J.Ankersmit (voorzitter) Heeft u vandaag genoten van onze uitvoering, dan is het misschien een goed idee om vriend van onze Oratoriumvereniging te worden. -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

Glimpses of Handel in the Choral-Orchestral Psalms of Mendelssohn

Glimpses of Handel in the Choral-Orchestral Psalms of Mendelssohn Zachary D. Durlam elix Mendelssohn was drawn to music of the Baroque era. His early training Funder Carl Friedrich Zelter included study and performance of works by Bach and Handel, and Mendelssohn continued to perform, study, and conduct compositions by these two composers throughout his life. While Mendels- sohn’s regard for J. S. Bach is well known (par- ticularly through his 1829 revival of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion), his interaction with the choral music of Handel deserves more scholarly at ten- tion. Mendelssohn was a lifelong proponent of Handel, and his contemporaries attest to his vast knowledge of Handel’s music. By age twenty- two, Mendelssohn could perform a number of Handel oratorio choruses from memory, and two years later, fellow musician Carl Breidenstein remarked that “[Mendelssohn] has complete knowledge of Handel’s works and has captured their spirit.”1 Zachary D. Durlam Director of Choral Activities Assistant Professor of Music University of Wisconsin Milwaukee [email protected] 28 CHORAL JOURNAL Volume 56 Number 10 George Frideric Handel Felix Mendelssohn Glimpses of Handel in the Choral- Mendelssohn’s self-perceived familiarity with Handel’s Mendelssohn’s Psalm 115 compositions is perhaps best summed up in the follow- and Handel’s Dixit Dominus ing anecdote about English composer William Sterndale During an 1829 visit to London, Mendelssohn was Bennett: allowed to examine Handel manuscripts in the King’s Library. Among these scores, he discovered and -

Mendelssohn Handbuch

MENDELSSOHN HANDBUCH Herausgegeben von Christiane Wiesenfeldt Bärenreiter Metzler Auch als eBook erhältlich (isbn 978-3-7618-7218-5) Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über www.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2020 Bärenreiter-Verlag Karl Vötterle GmbH & Co. KG, Kassel Gemeinschaftsausgabe der Verlage Bärenreiter, Kassel, und J. B. Metzler, Berlin Umschlaggestaltung: +christowzik scheuch design Umschlagabbildung: Wilhelm von Schadow: Mendelssohn, Ölgemälde (verschollen), Düsseldorf, ca. 1835; aus: Jacques Petitpierre, Le Mariage de Mendelssohn 1837–1937, Lausanne 1937; Reproduktion: dematon.de Lektorat: Jutta Schmoll-Barthel Korrektur: Daniel Lettgen, Köln Innengestaltung und Satz: Dorothea Willerding Druck und Bindung: Beltz Grafische Betriebe GmbH, Bad Langensalza isbn 978-3-7618-2071-1 (Bärenreiter) isbn 978-3-476-05630-6 (Metzler) www.baerenreiter.com www.metzlerverlag.de Inhalt Vorwort . IX Siglenverzeichnis XII Zeittafel . XIV I POSITIONEN, LEBENSWELTEN, KONTEXTE Romantisches Komponieren (von Christiane Wiesenfeldt) . 2 Mehrdeutigkeit als Deutungsproblem 2 Romantik als Deutungs-Option 5 Romantik im Werk 10 Mendels- sohns Modell von Romantik 15 Literatur 18 Jüdisch-deutsche und jüdisch-christliche Identität (von Jascha Nemtsov) . 21 »Lieben Sie mich, Brüderchen!«: Die Heimat 21 »Jener allweltliche Judensinn«: Die Aufklärung 23 »Hang zu allem Guten, Wahren und Rechten«: Die Taufe 25 »Ein Judensohn aber kein Jude«: Die Identität 27 Literatur 29 Ausbildung und Bildung (von R. Larry Todd) . 31 Mendelssohns frühe Ausbildung 31 Das familiäre Bildungsideal 32 Berliner Universität und »Grand Tour« 34 Lebenslanges Streben nach Bildung 35 Literatur 36 Die Familie (von Beatrix Borchard) . 37 Familienauftrag 38 Die Kernfamilie 39 Ehemann und Vater 42 Das öffentliche Bild der Familie Mendels- sohn 43 Literatur 45 Der Freundeskreis (von Michael Chizzali) . -

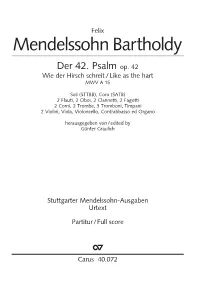

Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Der 42. Psalm op. 42 Wie der Hirsch schreit /Like as the hart MWV A 15 Soli (STTBB), Coro (SATB) 2 Flauti, 2 Oboi, 2 Clarinetti, 2 Fagotti 2 Corni, 2 Trombe, 3 Tromboni, Timpani 2 Violini, Viola, Violoncello, Contrabbasso ed Organo herausgegeben von/edited by Günter Graulich Stuttgarter Mendelssohn-Ausgaben Urtext Partitur/Full score C Carus 40.072 Inhalt Vorwort Dem heutigen Musikbetrieb dient Felix Mendelssohn Bar- liegen auch solche von Händel in Mendelssohns Bearbei- Vorwort / Foreword / Avant-propos 3 tholdy (1809–1847), der „romantische Klassizist“ (A. Ein- tungen und Ausgaben vor, so das Dettinger Te Deum, Acis stein) oder „klassizistische Romantiker“ (P. H. Lang), nur und Galatea sowie Israel in Ägypten. Hier hat Mendelssohn Faksimiles 8 mit einem schmalen Anteil seines reichen Werkes: mit Sin- nicht nur die Partituren nach den Originalquellen revidiert, fonien, Ouvertüren, dem Violin- und dem Klavierkonzert, sondern auch obligate Orgelpartien ausgeschrieben. der Musik zu Shakespeares Sommernachtstraum und weni- 1. Coro (SATB) 11 ger Kammermusik (z.B. dem Streicheroktett), Aufführun- Mendelssohn selbst hat sowohl geistliche A-cappella- Wie der Hirsch schreit gen seines gewichtigen und einst populären Oratorien- Musik „im alten Stil“ geschrieben als auch Werke mit As the hart longs spätlings Elias op. 70 (1846) sind heute selten. Und sein bei instrumentaler Begleitung. In der ersten Gruppe ragen das weitem originellstes Vokalwerk, die Erste Walpurgisnacht großartige achtstimmige Te Deum (1826) sowie die Mo- 2. Aria (Solo S) 26 op. 60 nach Goethe (zwei Fassungen: 1831 und 1843), von tetten op. 69, drei Psalmen op. 78 und Sechs Sprüche für Meine Seele dürstet nach Gott Berlioz gerühmt und ein Gipfel des Oratorienschaffens Doppelchor op. -

The Influence of German Literature on Music up to 1850

Mu^vo, uA> to 1^5*0 THE INFLUENCE OF GERMAN LITERATURE ON MUSIC UP TO 1850 BY MARY FERN JOHNSON THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC IN MUSIC SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1917 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 1, 19D7 THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY MARY FERN JOHNSON ENTITLED THE INFLUENCE Of GERMAN LITERATURE ON MUSIC U? TO 1850 IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC 376554 UIUC TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduetion Page I Part I Page 3 Part II Pag<i 34 Table I Page 134 Table II Page 135 Bibliography Page 136 # THE INFLUENCE OF GERMAN LITERATURE ON MUSIC UP TO 1850 INTRODUCTION German literature has exerted a broad influ- ence upon music; the legends which form the basis for the "best-known and best-loved literary gems, lending themselves especially to the musician 1 s fancy and im- agination. In dealing with this subject, those musical compositions which have 3ome literary background have been considered. Songs for one voice are not used, as they are innumerable, and furnish a subject for inves- tigation in themselves. Also Wagner T s operas were not con- sidered as they, with their legendary background have been much discussed by many critics and investigators. i M. A. Murphy-Legendary and Historical Sources of the Early Wagnerian Operas. M .L.Reuhe-sources of Wagner's "Der Ring des Nibelungen". Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/influenceofgerm.aOOjohn -2- Other opera texts have "been included; the libretto being in a class of literature by itself, not ordinarily thot of as literature, (literature, -meaning to the average in- dividual , poetry , and prose works , written as complete com- positions in themselves, with no anticipation of a musical setting) jthese operas are considered because they are based upon legends familiar in German literature, many of them being exactly the same plot and development as the lit- erary selection. -

ODE 1201-1 DIGITAL.Indd

ESTONIAN PHILHARMONIC CHAMBER CHOIR MENDELSSOHN DANIEL REUSS PSALMS KREEK 1 FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–1847) 1 Psalm 100 “Jauchzet dem Herrn, alle Welt”, Op. 69/2 4’27 CYRILLUS KREEK (1889–1962) 2 Psalm 22 “Mu Jumal! Mikspärast oled Sa mind maha jätnud?” 4’27 FELIX MENDELSSOHN 3 Psalms, Op. 78: 3 Psalm 2 “Warum toben die Heiden” 7’29 4 Psalm 43 “Richte mich, Gott” 4’31 5 Psalm 22 “Mein Gott, warum hast du mich verlassen?” * 8’08 * TIIT KOGERMAN, tenor CYRILLUS KREEK 6 Psalm 141 “Issand, ma hüüan Su poole” 2’27 7 Psalm 104 “Kiida, mu hing, Issandat!” 2’28 8 “Õnnis on inimene” 3’26 9 Psalm 137 “Paabeli jõgede kaldail” 6’40 FELIX MENDELSSOHN 10 “Hebe deine Augen” (from: Elijah, Op. 70) 2’16 11 “Denn er hat seinen Engeln befohlen” (from: Elijah, Op. 70) 3’32 12 “Wie selig sind die Toten”, Op. 115/1 3’30 2 CYRILLUS KREEK Sacred Folk Songs: 13 “Kui suur on meie vaesus” 2’43 14 “Jeesus kõige ülem hää” 1’54 15 “Armas Jeesus, Sind ma palun” 2’31 16 “Oh Jeesus, sinu valu” 2’03 17 “Mu süda, ärka üles” 1’43 ESTONIAN PHILHARMONIC CHAMBER CHOIR DANIEL REUSS, conductor Publishers: Carus-Verlag (Mendelssohn), SP Muusikaprojekt (Kreek) Recording: Haapsalu Dome Church, Estonia, 14–17.9.2009 Executive Producer: Reijo Kiilunen Recording and Post Production: Florian B. Schmidt ℗ 2012 Ondine Oy, Helsinki © 2012 Ondine Oy, Helsinki Booklet Editor: Elke Albrecht Translations to English: Kaja Kappel/Phyllis Anderson (liner notes), Kaja Kappel (tracks 13-17) Photos: Kaupo Kikkas (Niguliste Church in Tallinn – Front Cover; Daniel Reuss); Tõnis Padu (Haapsalu Dome Church) Design: Armand Alcazar 3 PSALMS BY FELIX MENDELSSOHN Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809–1847) was born in Germany into a family with Jewish roots; his grandfather was the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, his father a banker. -

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Sielminger Straße 51 Herr, Gedenke Nicht Op

Mendelssohn Bartholdy Das geistliche Vokalwerk · Sacred vocal music · Musique vocale sacrée Carus Alphabetisches Werkverzeichnis · Works listed alphabetically Adspice Domine. Vespergesang op. 121 25 Hymne op. 96 19, 27 Abendsegen. Herr, sei gnädig 26 Ich harrete des Herrn 30 Das geistliche Vokalwerk · The sacred vocal works · La musique vocale sacrée 4 Abschied vom Walde op. 59,3 33 Ich weiche nicht von deinen Rechten 29 Die Stuttgarter Mendelssohn-Ausgaben · The Stuttgart Mendelssohn Editions Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein 15 Ich will den Herrn preisen 29 Les Éditions Mendelssohn de Stuttgart 8 Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr 26 Jauchzet dem Herrn in A op. 69,2 28 Orchesterbegleitete Werke · Works with orchestra · Œuvres avec orchestre Alleluja (aus Deutsche Liturgie) 26, 27 Jauchzet dem Herrn in C 30 Amen (aus Deutsche Liturgie) 26, 27 Jauchzet Gott, alle Lande 29 – Die drei Oratorien · The three oratorios · Les trois oratorios 11 Auf Gott allein will hoffen ich 26 Jesu, meine Freude 17 – Die fünf Psalmen · The five psalms · Les cinq psaumes 13 Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir op. 23,1 27 Jesus, meine Zuversicht 30 – Die acht Choralkantaten · The eight chorale cantatas · Les huit cantates sur chorals 15 Ave Maria op. 23,2 27 Jube Domne 31 – Lateinische und deutsche Kirchenmusik · Latin and German church music Ave maris stella 24 Kyrie in A (aus Deutsche Liturgie) 26, 27 Musique sacrée latine et allemande 19 Beati mortui / Selig sind op. 115,1 25 Kyrie in c 31 Werke für Solostimme · Works for solo voice · Œuvres pour voix solo 24 Cantique pour l’Eglise Wallonne 26, 31 Kyrie in d 21 Christe, du Lamm Gottes 15 Lasset uns frohlocken op. -

Season Brochure

Brookline, MA 02446 MA Brookline, 1428 PO Box Music Director Lisa Graham, CHORALE METROPOLITAN METROPOLITAN Lisa Graham, CHORALE the Evelyn Barry Director 2019–2020 of Choral Programs at Wellesley College, is beginning her 16th Lisa Graham season as Music Direc- Music Director Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, Op. 125 with New Philharmonia Orchestra Op. 9, No. Symphony Beethoven’s – with Original Gravity Girl Passion Match Little The David Lang’s Exhibitions the International from Musical portraits Fair: World’s – with New England Philharmonic Apart and Together Musica Opus 60 with Chorus Pro Walpurgisnacht, Die erste tor of the Metropolitan Chorale. Dr. Graham has grown the chorale to over 100 members and has shaped the programming to include contemporary, Ameri- can, and lesser-known programs,alongside the masterworks of the repertory. In a review of her guest appearance conducting the Metro- politan Chorale and the Boston Pops, Broad- way World praised Dr. Graham as “a spellbind- ing maestro, balletic in her direction … a great connection with her performers on stage.” Be Inspired. Be Moved. Be Uplifted. PERMIT NO. 538 NO. PERMIT ORGANIZATION BOSTON, MA BOSTON, US POSTAGE NONPROFIT PAID Plus our Holiday Pops Tour! FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 8, 2019 HOLIDAY POPS 2019 SUNDAY, MARCH 15, 2020 8pm • Jordan Hall • Boston WITH KEITH LOCKHART 3pm • Sanders Theater CHORUS PRO MUSICA and The Chorale joins Keith Lockhart Cambridge METROPOLITAN CHORALE and the Boston Pops on their WORLD’S FAIR: MUSICAL PORTRAITS FROM Jamie Kirsch and Lisa Graham, Conductors annual Holiday Tour THE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS Felix Mendelssohn: DIE ERSTE • Saturday, November 30 • 8:00pm Providence Performing Arts Center – Providence, RI Come hear the musical stories from the World Expositions WALPURGISNACHT, OPUS 60 (1843) of Paris, London, New York, Chicago, and bring fresh ears to Zoltán Kodály: BUDAVÁRI TE DEUM (1936) • Sunday, December 1 • 4:00pm what an imagined World’s Fair might be in Boston, 2020. -

Ein Sommernachtstraum Die Erste Walpurgisnacht

FELIX MENDELSSOHN BARTHOLDY Ein Sommernachtstraum Musik zum Schauspiel Die erste Walpurgisnacht Kantate So, 28. April 2019 | 17 Uhr Liederhalle Stuttgart, Hegelsaal LEITUNG: FRIEDER BERNIUS Kammerchor Stuttgart Die Deutsche Kammer- phil harmonie Bremen Renée Morloc ALT David Fischer TENOR Thomas E. Bauer BARITON Programm David Jerusalem BASS 1 PROGRAMM Das Musik Podium Stuttgart dankt seinen institutionellen Förderern, dem Kulturamt der Sonntag, 28. April 2019 | 17 Uhr Stadt Stuttgart und dem Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst Baden-Würt- Liederhalle Stuttgart, Hegelsaal temberg, sowie seinen Sponsoren, Projektförderern, Kooperationspartnern und Freunden für die freundliche Unterstützung. FELIX MENDELSSOHN BARTHOLDY (1809–1847) Ein Sommernachtstraum op. 61 Musik zum Schauspiel von William Shakespeare PAUSE Die erste Walpurgisnacht op. 60 Kantate für Soli, Chor und Orchester, FREUNDE DES nach der Ballade von Johann Wolfgang von Goethe MUSIK PODIUM STUTTGART Renée Morloc ALT David Fischer TENOR Impressum Thomas E. Bauer BARITON Veranstalter: Musik Podium Stuttgart e. V. David Jerusalem BASS Büchsenstraße 22 | 70174 Stuttgart Tel. 0711 239139 0 | Fax 0711 239139 9 Kammerchor Stuttgart [email protected] | www.musikpodium.de Künstlerische Leitung: Prof. Frieder Bernius Die Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen Geschäftsführung: Matthias Begemann Projekt-/Orchestermanagement: Lena Schiller Frieder Bernius Chormanagement: Sandra Bernius Künstlerisches Betriebsbüro: Lisa Wegener Redaktion: Birgit Meilchen, Veronika Schmitt Gestaltung: Bernd Allgeier · www.berndallgeier.de Dauer: 90 Minuten mit Pause 2 3 GOETHES BALLADE GOETHES BALLADE Und wachet hier im stillen, Dem Feinde viel erlauben. Wenn sie die Pflicht erfüllen. Die Flamme reinigt sich vom Rauch: JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE (1749–1832) So reinig unsern Glauben! Ein Wächter Und raubt man uns den alten Brauch: Diese dumpfen Pfaffenchristen, Dein Licht, wer will es rauben! Laßt uns keck sie überlisten! Die erste Mit dem Teufel, den sie fabeln, Ein christlicher Wächter Wollen wir sie selbst erschrecken. -

Mendelssohn: Symphony No 2 'Lobgesang'

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live Mendelssohn Symphony No 2 ‘Lobgesang’ Sir John Eliot Gardiner Lucy Crowe Jurgita Adamonytė Michael Spyres Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) Page Index Symphony No 2 in B-flat major, ‘Lobgesang’ (Hymn of Praise), Op 52 (1840) 3 Programme notes Sir John Eliot Gardiner 4 Notes de programme London Symphony Orchestra 6 Einführungstexte Lucy Crowe soprano Jurgita Adamonytė mezzo-soprano Michael Spyres tenor 8 Spoken & sung texts 11 Conductor biography Monteverdi Choir 12 Soloist biographies 15 Choir biography & personnel list Symphony No 2, ‘Lobgesang’ (Hymn of Praise) 16 Orchestra personnel list 1 – Maestoso con moto 11’47’’ No 1 Sinfonia 17 LSO biography 2 No 1 Sinfonia – Allegretto un poco agitato 6’06’’ 3 No 1 Sinfonia – Adagio religioso 6’25’’ 4 No 2 Allegro moderato maestoso “Alles, was Odem hat, lobe den Herrn” 4’09’’ 5 No 2 Molto più moderato ma con fuoco “Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele” 2’44’’ 6 No 3 Recitativo – “Saget es, die ihr erlöst seid durch den Herrn” 0’52’’ 7 No 3 Allegro moderato “Er zählet unsre Tränen” 2’17’’ 8 No 4 Chor – A tempo moderato “Sagt es, die ihr erlöset seid” 1’47’’ 9 No 5 Andante “Ich harrete des Herrn” 5’28’’ 10 No 6 Allegro un poco agitato “Stricke des Todes hatten uns umfangen” 4’04’’ 11 No 7 Allegro maestoso e molto vivace “Die Nacht ist vergangen” 4’17’’ 12 No 8 Choral – Andante con moto “Nun danket alle Gott” 1’33’’ 13 No 8 Un poco più animato “Lob, Ehr und Preis sei Gott” 2’56’’ 14 No 9 Andante sostenuto assai “Drum sing’ ich mit -

Mendelssohn's DIE ERSTE WALPURGISNACHT Beethoven's CHORAL FANTASY and OPFERLIED

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon tile quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1 The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)" If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity 2 When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame If copynghted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3 When a map, drawing or chart, etc , is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of "sectioning" the material has been followed It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete 4.