Glimpses of Handel in the Choral-Orchestral Psalms of Mendelssohn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Book of Psalms “Bless the Lord, O My Soul, and Forget Not All His Benefits” (103:2)

THE BOOK OF PSALMS “BLESS THE LORD, O MY SOUL, AND FORGET NOT ALL HIS BENEFITS” (103:2) BOOK I BOOK II BOOK III BOOK IV BOOK V 41 psalms 31 psalms 17 psalms 17 psalms 44 psalms 1 41 42 72 73 89 90 106 107 150 DOXOLOGY AT THESE VERSES CONCLUDES EACH BOOK 41:13 72:18-19 89:52 106:48 150:6 JEWISH TRADITION ASCRIBES TOPICAL LIKENESS TO PENTATEUCH GENESIS EXODUS LEVITICUS NUMBERS DEUTERONOMY ────AUTHORS ──── mainly mainly (or all) DAVID mainly mainly mainly DAVID and KORAH ASAPH ANONYMOUS DAVID BOOKS II AND III ADDED MISCELLANEOUS ORIGINAL GROUP BY DURING THE REIGNS OF COLLECTIONS DAVID HEZEKIAH AND JOSIAH COMPILED IN TIMES OF EZRA AND NEHEMIAH POSSIBLE CHRONOLOGICAL STAGES IN THE GROWTH AND COLLECTION OF THE PSALTER 1 The Book of Psalms I. Book Title The word psalms comes from the Greek word psalmoi. It suggests the idea of a “praise song,” as does the Hebrew word tehillim. It is related to a Hebrew concept which means “the plucking of strings.” It means a song to be sung to the accompaniment of stringed instruments. The Psalms is a collection of worship songs sung to God by the people of Israel with musical accompaniment. The collection of these 150 psalms into one book served as the first hymnbook for God’s people, written and compiled to assist them in their worship of God. At first, because of the wide variety of these songs, this praise book was unnamed, but eventually the ancient Hebrews called it “The Book of Praises,” or simply “Praises.” This title reflects its main purpose──to assist believers in the proper worship of God. -

Najaarsconcert 2018 2

NAJAARSCONCERT 2018 2 Welkom Beste concertbezoeker, Ik heet u namens de Oratoriumvereniging van harte welkom bij ons najaarsconcert in deze prachtige Martinikerk van Bolsward. Dit concert staat in het teken van Jacob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (geboren 3 februari 1809 en overleden op 4 november 1847). Hij was een Duitse componist, pianist, organist en dirigent in de vroeg romantische periode. Mendelssohn schreef symfonieën, concerten, oratoria, pianomuziek en kamermuziek. Hij vierde zijn successen in Duitsland en liet de muziek van Johann Sebastian Bach herleven. Vanmiddag voeren wij twee werken van hem uit: het Lobgesang en Psalm 42. Verder zal onze organist nog een sonate van Mendelssohn spelen. Onze uitvoering vanmiddag is een bijzondere uitvoering. Zoals u ziet zijn het koor, het orkest en de solisten geplaatst op een speciaal voor deze uitvoering gemaakt podium vlak voor het prachtige kerkorgel, dat meewerkt aan de uitvoering. U, als publiek zit nu ook andersom. Wij willen vandaag als koor ervaren hoe deze opstelling bevalt. Mocht dat positief zijn, dan zullen we in de toekomst waarschijnlijk vaker gebruik gaan maken van deze opstelling. In dit concertboekje kunt u verder alle informatie over dit concert lezen. Ook is er een plattegrond opgenomen waarop staat aangegeven waar de toiletten zijn en waar de nooduitgangen zich bevinden. Graag deze plattegrond voor aanvang van het concert goed bekijken. Volgend jaar voeren wij in de week voor Pasen weer tweemaal de Matthäus-Passion uit en in het najaar de volledige uitvoering van de Messiah van Händel. We hopen u dan ook als luisteraar te mogen begroeten. Met vriendelijke groeten, G.J.Ankersmit (voorzitter) Heeft u vandaag genoten van onze uitvoering, dan is het misschien een goed idee om vriend van onze Oratoriumvereniging te worden. -

The Importance of the Dead Sea Scrolls for the Study of the Explicit Quotations in Ad Hebraeos

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 9 Original Research The importance of the Dead Sea Scrolls for the study of the explicit quotations inAd Hebraeos Author: The important contribution that the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) hold for New Testament studies is Gert J. Steyn¹ probably most evident in Ad Hebraeos. This contribution seeks to present an overview of Affiliation: relevant extant DSS fragments available for an investigation of the Old Testament explicit 1Department of New quotations and motifs in the book of Hebrews. A large number of the explicit quotations in Testament Studies, Faculty of Hebrews were already alluded to, or even quoted, in some of the DSS. The DSS are of great Theology, University of importance for the study of the explicit quotations in Ad Hebraeos in at least four areas, namely Pretoria, South Africa in terms of its text-critical value, the hermeneutical methods employed in both the DSS and Project leader: G.J. Steyn Hebrews, theological themes and motifs that surface in both works, and the socio-religious Project number: 02378450 background in which these quotations are embedded. After these four areas are briefly explored, this contribution concludes, among others, that one can cautiously imagine a similar Description Jewish sectarian matrix from which certain Christian converts might have come – such as the This research is part of the project, ‘Acts’, directed by author of Hebrews himself. Prof. Dr Gert Steyn, Department of New Testament Studies, Faculty of Theology, University of Introduction Pretoria. The relation between the text readings found among the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), those of the LXX witnesses and the quotations in Ad Hebraeos1 needs much more attention (Batdorf 1972:16–35; Corresponding author: 2 Gert Steyn, Bruce 1962/1963:217–232; Grässer 1964:171–176; Steyn 2003a:493–514; Wilcox 1988:647–656). -

The Letter to the Hebrews

Click here for an article on Hebrews from The Oxford Companion to the Bible, ed. Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, New York and London, 1993. PARALLEL GUIDE 31 The Letter to the Hebrews Summary The Letter to the Hebrews is a strong statement of faith which proclaims Jesus Christ, yesterday, today, and forever. It emphasizes the divine and human natures of Christ. Written in classical Greek prose, its authorship, origin, destination, and date are not known; it is probably not a letter; and it contains much which is of lasting value to the church. Learning Objectives • Read the Letter to the Hebrews • Learn the general form and outline of the Letter to the Hebrews • Understand the key messages and metaphors of the Letter to the Hebrews • Discover the link between the Letter to the Hebrews and the literature of the Old Testament as well as other Semitic literature of the era • Undersand the christology of the Letter to the Hebrews Assignment to Deepen Your Understanding 1. Select a passage from the Letter to the Hebrews for reflection and read it several times. Allow whatever ideas that surface to come forth. You may wish to keep these in a notebook. 2. The EfM text suggests that the message in the Letter to the Hebrews deserves to be better known. Is this something you believe? What would be the best way to make its message known to others? 3. Examine the christology of the Letter to the Hebrews, that is, what it tells us about Christ. What ideas about the nature and work of Jesus Christ are sparked for you as you examine this letter? Preparing for Your Seminar Focus on the meaning of the mixed metaphor, “Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses . -

10 Hebrew Words for Praise 1. Yadah – to Revere, Give Thanks, Praise

10 Hebrew Words for Praise 1. Yadah – To revere, give thanks, praise Literally, this word means to extend or throw the hand. And it’s used elsewhere in the OT to refer to one casting stones or pulling back the bow. In an attempt to revere, in an attempt to give thanks, the human response to God is to extend your hands, to reach out in response to God. • Psalm 145:10 - “All your works shall give thanks to you, O Lord, and all Your saints shall bless You!” All creation reaches out in thanks and praise back toward the creator. • Psalm 139:14 - “I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.” I praise you, I extend my hands to you for I am fearfully and wonderfully made by you. • Psalm 97:12 – “Rejoice in the Lord O you righteous, and give thanks to His holy name!” Yada means to give thanks, to revere, to praise by a physical throwing of the hands. 2. Barach – To bless, to praise as a blessing Literally, this word means to bow or to kneel. It’s what a person does when they come into the presence of a King. It’s an expression of humility. • Psalm 145:1 – “I will extol you, my God my King, and bless Your name forever and ever.” Verse 2- same thing- “Every day I will bless you (barach) and praise Your name forever.” • Psalm 95:6 - “Oh come, let us worship and bow down; let us kneel before the Lord our Maker!” In this verse the psalmist uses 3 different words- “Come let us worship (literally shachah- bow down prostrate) and bow down (kara – crouch low), let us kneel (barach)- 3 different words that all mean some form of bowing down, crouching down, kneeling before… blessing in honor before. -

Complex Antiphony in Psalms 121, 126 and 128: the Steady Responsa Hypothesis

502 Amzallag & Avriel: Complex Antiphony in Pss OTE 23/3 (2010), 502-518 Complex Antiphony in Psalms 121, 126 and 128: the Steady Responsa Hypothesis NISSIM AMZALLAG AND MIKHAL AVRIEL (I SRAEL ) ABSTRACT Psalms 121, 126 and 128 are three songs of Ascents displaying the same structural characteristics: (i) they include two distinct parts, each one with its own theme; (ii) the two parts have the same number of verse lines;, (iii) many grammatical and semantic similarities are found between the homolog verse lines from the two parts; (iv) a literary breakdown exists between the last verse of the first part and the first verse of the second part. These features remain unexplained as long as these poems are approached in a linear fashion. Here we test the hypothesis that these songs were performed antiphonally by two choirs, each one singing another part of the poem. This mode of complex antiphony is defined here as steady responsa. In the three songs analyzed here, the “composite text” issued from such a pairing of distant verses displays a high level of coherency, new literary properties, images and metaphors, echo patterns typical to antiphony and even “composite meanings” ignored by the linear reading. We conclude that these three psalms were originally conceived to be performed as steady responsa. A INTRODUCTION Antiphony is sometimes mentioned in the Bible. The first ceremony of alliance of the Israelites in Canaan is reported as an impressive antiphonal dialogue between two Israelite choirs: from mount Gerizim six tribes were to bless the people and from mount Eybal a responding choir of the other six tribes were to sing a hymn of curse (Deut 27:11-16). -

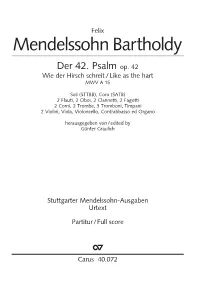

Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Der 42. Psalm op. 42 Wie der Hirsch schreit /Like as the hart MWV A 15 Soli (STTBB), Coro (SATB) 2 Flauti, 2 Oboi, 2 Clarinetti, 2 Fagotti 2 Corni, 2 Trombe, 3 Tromboni, Timpani 2 Violini, Viola, Violoncello, Contrabbasso ed Organo herausgegeben von/edited by Günter Graulich Stuttgarter Mendelssohn-Ausgaben Urtext Partitur/Full score C Carus 40.072 Inhalt Vorwort Dem heutigen Musikbetrieb dient Felix Mendelssohn Bar- liegen auch solche von Händel in Mendelssohns Bearbei- Vorwort / Foreword / Avant-propos 3 tholdy (1809–1847), der „romantische Klassizist“ (A. Ein- tungen und Ausgaben vor, so das Dettinger Te Deum, Acis stein) oder „klassizistische Romantiker“ (P. H. Lang), nur und Galatea sowie Israel in Ägypten. Hier hat Mendelssohn Faksimiles 8 mit einem schmalen Anteil seines reichen Werkes: mit Sin- nicht nur die Partituren nach den Originalquellen revidiert, fonien, Ouvertüren, dem Violin- und dem Klavierkonzert, sondern auch obligate Orgelpartien ausgeschrieben. der Musik zu Shakespeares Sommernachtstraum und weni- 1. Coro (SATB) 11 ger Kammermusik (z.B. dem Streicheroktett), Aufführun- Mendelssohn selbst hat sowohl geistliche A-cappella- Wie der Hirsch schreit gen seines gewichtigen und einst populären Oratorien- Musik „im alten Stil“ geschrieben als auch Werke mit As the hart longs spätlings Elias op. 70 (1846) sind heute selten. Und sein bei instrumentaler Begleitung. In der ersten Gruppe ragen das weitem originellstes Vokalwerk, die Erste Walpurgisnacht großartige achtstimmige Te Deum (1826) sowie die Mo- 2. Aria (Solo S) 26 op. 60 nach Goethe (zwei Fassungen: 1831 und 1843), von tetten op. 69, drei Psalmen op. 78 und Sechs Sprüche für Meine Seele dürstet nach Gott Berlioz gerühmt und ein Gipfel des Oratorienschaffens Doppelchor op. -

Psalm 95 Outline

Women in the Word -Psalms for the Heart Marilynn Miller Psalm #95 –Worship – or Else! April 5, 2017 I. The Way vs 1-2, 6 Psalm 95:1-2 “1 Oh come, let us sing to the LORD; let us make a joyful noise to the rock of our salvation! 2 Let us come into his presence with thanksgiving; let us make a joyful noise to him with songs of praise! “ “6 Oh come, let us worship and bow down; let us kneel before the LORD, our Maker!” A. God is to be worshipped corporately. Corporate worship is the community of faith gathering in unity to worship our God. And we have the expectation that God gathers in our midst. Hebrews 10:24-25 “And let us consider how to stir up one another to love and good works, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day drawing near.” B. God is to be worshipped with joy 1. Joy is a delight created within us by the Holy Spirit. It is one of His gifts that He bestows upon His people – the fruit of the Spirit. Galatians 5:22-23 “But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control; against such things there is no law.” 2. Joy is not unbridled emotion. Christian joy is focused upon Christ and is harnessed by objective truth and holy reverence. It is a fervency based upon a delight in the Biblical Christ. -

ODE 1201-1 DIGITAL.Indd

ESTONIAN PHILHARMONIC CHAMBER CHOIR MENDELSSOHN DANIEL REUSS PSALMS KREEK 1 FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–1847) 1 Psalm 100 “Jauchzet dem Herrn, alle Welt”, Op. 69/2 4’27 CYRILLUS KREEK (1889–1962) 2 Psalm 22 “Mu Jumal! Mikspärast oled Sa mind maha jätnud?” 4’27 FELIX MENDELSSOHN 3 Psalms, Op. 78: 3 Psalm 2 “Warum toben die Heiden” 7’29 4 Psalm 43 “Richte mich, Gott” 4’31 5 Psalm 22 “Mein Gott, warum hast du mich verlassen?” * 8’08 * TIIT KOGERMAN, tenor CYRILLUS KREEK 6 Psalm 141 “Issand, ma hüüan Su poole” 2’27 7 Psalm 104 “Kiida, mu hing, Issandat!” 2’28 8 “Õnnis on inimene” 3’26 9 Psalm 137 “Paabeli jõgede kaldail” 6’40 FELIX MENDELSSOHN 10 “Hebe deine Augen” (from: Elijah, Op. 70) 2’16 11 “Denn er hat seinen Engeln befohlen” (from: Elijah, Op. 70) 3’32 12 “Wie selig sind die Toten”, Op. 115/1 3’30 2 CYRILLUS KREEK Sacred Folk Songs: 13 “Kui suur on meie vaesus” 2’43 14 “Jeesus kõige ülem hää” 1’54 15 “Armas Jeesus, Sind ma palun” 2’31 16 “Oh Jeesus, sinu valu” 2’03 17 “Mu süda, ärka üles” 1’43 ESTONIAN PHILHARMONIC CHAMBER CHOIR DANIEL REUSS, conductor Publishers: Carus-Verlag (Mendelssohn), SP Muusikaprojekt (Kreek) Recording: Haapsalu Dome Church, Estonia, 14–17.9.2009 Executive Producer: Reijo Kiilunen Recording and Post Production: Florian B. Schmidt ℗ 2012 Ondine Oy, Helsinki © 2012 Ondine Oy, Helsinki Booklet Editor: Elke Albrecht Translations to English: Kaja Kappel/Phyllis Anderson (liner notes), Kaja Kappel (tracks 13-17) Photos: Kaupo Kikkas (Niguliste Church in Tallinn – Front Cover; Daniel Reuss); Tõnis Padu (Haapsalu Dome Church) Design: Armand Alcazar 3 PSALMS BY FELIX MENDELSSOHN Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809–1847) was born in Germany into a family with Jewish roots; his grandfather was the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, his father a banker. -

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Sielminger Straße 51 Herr, Gedenke Nicht Op

Mendelssohn Bartholdy Das geistliche Vokalwerk · Sacred vocal music · Musique vocale sacrée Carus Alphabetisches Werkverzeichnis · Works listed alphabetically Adspice Domine. Vespergesang op. 121 25 Hymne op. 96 19, 27 Abendsegen. Herr, sei gnädig 26 Ich harrete des Herrn 30 Das geistliche Vokalwerk · The sacred vocal works · La musique vocale sacrée 4 Abschied vom Walde op. 59,3 33 Ich weiche nicht von deinen Rechten 29 Die Stuttgarter Mendelssohn-Ausgaben · The Stuttgart Mendelssohn Editions Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein 15 Ich will den Herrn preisen 29 Les Éditions Mendelssohn de Stuttgart 8 Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr 26 Jauchzet dem Herrn in A op. 69,2 28 Orchesterbegleitete Werke · Works with orchestra · Œuvres avec orchestre Alleluja (aus Deutsche Liturgie) 26, 27 Jauchzet dem Herrn in C 30 Amen (aus Deutsche Liturgie) 26, 27 Jauchzet Gott, alle Lande 29 – Die drei Oratorien · The three oratorios · Les trois oratorios 11 Auf Gott allein will hoffen ich 26 Jesu, meine Freude 17 – Die fünf Psalmen · The five psalms · Les cinq psaumes 13 Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir op. 23,1 27 Jesus, meine Zuversicht 30 – Die acht Choralkantaten · The eight chorale cantatas · Les huit cantates sur chorals 15 Ave Maria op. 23,2 27 Jube Domne 31 – Lateinische und deutsche Kirchenmusik · Latin and German church music Ave maris stella 24 Kyrie in A (aus Deutsche Liturgie) 26, 27 Musique sacrée latine et allemande 19 Beati mortui / Selig sind op. 115,1 25 Kyrie in c 31 Werke für Solostimme · Works for solo voice · Œuvres pour voix solo 24 Cantique pour l’Eglise Wallonne 26, 31 Kyrie in d 21 Christe, du Lamm Gottes 15 Lasset uns frohlocken op. -

At Church of the King on October 18Th, 2020 the 20Th Sunday of Ordinary Time

At Church of the King on October 18th, 2020 The 20th Sunday of Ordinary Time “How sweet are Your words to my taste, Sweeter than honey to my mouth!" Psalms 119:103 Hear Today’s Call to Worship From God’s Word “Oh come, let us sing to Jehovah! Let us shout joyfully to the Rock of our salvation. Let us come before His presence with thanksgiving; Let us shout joyfully to Him with psalms. For Jehovah is the great God, And the great King above all gods. In His hand are the deep places of the earth; the heights of the hills are His also. The sea is His, for He made it; and His hands formed the dry land. Oh come, let us worship and bow down; Let us kneel before Jehovah our Maker” Psalm 95:1-7 God’s People Respond with a Hymn of Adoration: (Based on Psalm 145:10) O worship the King all glorious above, The earth with its store of wonders untold O gratefully sing his power and His love. Almighty, thy power hath founded of old; Our shield and defender, the ancient of days, Hath stablished it fast by a changeless decree Pavilioned in splendor and girded with praise. And round it hath cast, like a mantle, the sea. Salutation and Response: [based on Matthew 28:19, Ruth 2:4 and Psalm 103:13] In the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit Amen! Jehovah be with you! And also with you! As a father has compassion on his children, So Jehovah has compassion on those who fear Him 1 Confession of Sins: Where God Cleanses Us In Christ The Call for Confession from God’s Word: “Have mercy upon me, O God, According to Your loving kindness; According to the multitude of Your tender mercies, Blot out my transgressions. -

Fact Sheet for “Oh Come, Let Us Worship and Bow Down” Psalm 95 Pastor Bob Singer 02/02/2020

Fact Sheet for “Oh Come, Let Us Worship and Bow Down” Psalm 95 Pastor Bob Singer 02/02/2020 We sing these words from Psalm 95… 6 Oh come, let us worship and bow down; let us kneel before the LORD, our Maker! 7a For he is our God, and we are the people of his pasture, and the sheep of his hand. “From the seventeenth century Psalms 95-99 and 29 were included in the Jewish liturgy for the inauguration of the Sabbath.”1 There is also an early Christian chant, first appearing in the 13th century, based on Psalm 95:1-7a; 96:9, 13… with a benediction added. It is called the “Venite” in Latin. The Septuagint for Psalm 95 has the following as part of a superscription: “When the house was being rebuilt after the captivity”, referring to the Babylonian captivity. Although this superscription does not appear in our Bibles it may be the actual history of this Psalm. Verses 1&2 are an invitation to sing to God. ESV 1 Oh come, let us sing to the LORD; let us make a joyful noise to the rock of our salvation! The words “let us” are sort of a command to ourselves. The first reference I found to the “rock of our salvation’ is in Deuteronomy 32:15 where Israel scoffed at the Rock of their salvation instead of singing to him. The psalmist urged his readers to sing to the rock of their salvation like David did (2 Samuel 22:1, 47). 2 Let us come into his presence with thanksgiving; let us make a joyful noise to him with songs of praise! Verses 3-5 speak of God’s greatness in creation.