A STUDY of the HEBREW TEXT of PSALM 132 a Thesis Presented In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past, Present, and Future FIFTY YEARS of ANTHROPOLOGY in SUDAN

Past, present, and future FIFTY YEARS OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN SUDAN Munzoul A. M. Assal Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil Past, present, and future FIFTY YEARS OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN SUDAN Munzoul A. M. Assal Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil FIFTY YEARS OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN SUDAN: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE Copyright © Chr. Michelsen Institute 2015. P.O. Box 6033 N-5892 Bergen Norway [email protected] Printed at Kai Hansen Trykkeri Kristiansand AS, Norway Cover photo: Liv Tønnessen Layout and design: Geir Årdal ISBN 978-82-8062-521-2 Contents Table of contents .............................................................................iii Notes on contributors ....................................................................vii Acknowledgements ...................................................................... xiii Preface ............................................................................................xv Chapter 1: Introduction Munzoul A. M. Assal and Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil ......................... 1 Chapter 2: The state of anthropology in the Sudan Abdel Ghaffar M. Ahmed .................................................................21 Chapter 3: Rethinking ethnicity: from Darfur to China and back—small events, big contexts Gunnar Haaland ........................................................................... 37 Chapter 4: Strategic movement: a key theme in Sudan anthropology Wendy James ................................................................................ 55 Chapter 5: Urbanisation and social change in the Sudan Fahima Zahir El-Sadaty ................................................................ -

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible is Tehillim, which means "praise songs." The title adopted by the Septuagint translators for their Greek version was Psalmoi meaning "songs to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument." This Greek word translates the Hebrew word mizmor that occurs in the titles of 57 of the psalms. In time the Greek word psalmoi came to mean "songs of praise" without reference to stringed accompaniment. The English translators transliterated the Greek title resulting in the title "Psalms" in English Bibles. WRITERS The texts of the individual psalms do not usually indicate who wrote them. Psalm 72:20 seems to be an exception, but this verse was probably an early editorial addition, referring to the preceding collection of Davidic psalms, of which Psalm 72 was the last.1 However, some of the titles of the individual psalms do contain information about the writers. The titles occur in English versions after the heading (e.g., "Psalm 1") and before the first verse. They were usually the first verse in the Hebrew Bible. Consequently the numbering of the verses in the Hebrew and English Bibles is often different, the first verse in the Septuagint and English texts usually being the second verse in the Hebrew text, when the psalm has a title. ". there is considerable circumstantial evidence that the psalm titles were later additions."2 However, one should not understand this statement to mean that they are not inspired. As with some of the added and updated material in the historical books, the Holy Spirit evidently led editors to add material that the original writer did not include. -

Daily Devotions in the Psalms Psalm 129-133

Daily Devotions in the Psalms Psalm 129-133 Monday 12th October - Psalm 129 “Greatly have they afflicted me from my youth”— let Israel now say— 2 “Greatly have they afflicted me from my youth, yet they have not prevailed against me. 3 The plowers ploughed upon my back; they made long their furrows.” 4 The Lord is righteous; he has cut the cords of the wicked. 5 May all who hate Zion be put to shame and turned backward! 6 Let them be like the grass on the housetops, which withers before it grows up, 7 with which the reaper does not fill his hand nor the binder of sheaves his arms, 8 nor do those who pass by say, “The blessing of the Lord be upon you! We bless you in the name of the Lord!” It is interesting that Psalm 128 and 129 sit side by side. They seem to sit at odds with one another. Psalm 128 speaks of Yahweh blessing his faithful people. They enjoy prosperity and the fruit of their labour. It is a picture of peace and blessing. And then comes this Psalm, clunking like a car accidentally put into reverse. Here we see a people long afflicted (v. 1-2). As a nation, they have had their backs ploughed. And the rest of the Psalm prays for the destruction of the wicked nations and individuals who would seek to harm and destroy Israel. It’s possible that this Psalm makes you feel uncomfortable, or even wonder if this Psalm is appropriate for the lips of God’s people. -

Psalm 2 the Lord's Reign Ruins the Rebellious and Rescues the Faithful

Psalm 2 The Lord’s Reign ruins the rebellious and rescues the faithful Nov. 15, 2015 I like sitting in my front yard or resting on my front porch when I have a porch of any size. When I don’t, the yard does just fine. Right before we moved to Bloomfield a few weeks ago, in the fading sunlight of a fall afternoon, the rumble of a Harley Davidson V-Twin eased to a stop right in front of me. So here I am, enjoying the last hours of a pleasant afternoon at our Windsor apartment. Next thing I know, the biker asks, above the Harley's rumble, “Is there a liquor store around here?” I point down the street, to the east at a little strip mall. “Yeah, there's one in that strip mall, just past the Italian restaurant.” He said, “I just go past that green awning and it's right there?” “Yeah,” I said. “It's right there.” At that point, I noticed a cross on his bandanna. The bandanna was folded just so, and positioned on the man's head just right. The cross was clearly seen, burnt orange on a black background. So I asked him, “Are you a Christian?” “No,” he said. “Oh, OK, I saw the cross on your bandanna but, no offense, I didn't think you were.” To which he said, “Well, I'm a Christian, I'm just not practicing.” stand up When Andre started this sermon series in September, he made this statement early in his first sermon: “The question is not, ‘Are you pursuing a kingdom? But whose kingdom are you pursuing?’” I think the stranger looking for a liquor store thought he could pay lip service to one thing and practice another. -

Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016)

James Block Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016) Contents ARISE OH YAH (Psalm 68) .............................................................................................................................................. 3 AWAKE JERUSALEM (Isaiah 52) ................................................................................................................................... 4 BLESS YAHWEH OH MY SOUL (Psalm 103) ................................................................................................................ 5 CITY OF ELOHIM (Psalm 48) (Capo 1) .......................................................................................................................... 6 DANIEL 9 PRAYER .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 DELIGHT ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 FATHER’S HEART ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 FIRSTBORN ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GREAT IS YOUR FAITHFULNESS (Psalm 92) ............................................................................................................. 11 HALLELUYAH -

9781845502027 Psalms Fotb

Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................7 Notes ............................................................................................................. 8 Psalm 90: Consumed by God’s Anger ......................................................9 Psalm 91: Healed by God’s Touch ...........................................................13 Psalm 92: Praise the Ltwi ........................................................................17 Psalm 93: The King Returns Victorious .................................................21 Psalm 94: The God Who Avenges ...........................................................23 Psalm 95: A Call to Praise .........................................................................27 Psalm 96: The Ltwi Reigns ......................................................................31 Psalm 97: The Ltwi Alone is King ..........................................................35 Psalm 98: Uninhibited Rejoicing .............................................................39 Psalm 99: The Ltwi Sits Enthroned ........................................................43 Psalm 100: Joy in His Presence ................................................................47 Psalm 101: David’s Godly Resolutions ...................................................49 Psalm 102: The Ltwi Will Rebuild Zion ................................................53 Psalm 103: So Great is His Love. .............................................................57 -

Copyright © 2016 Matthew Habib Emadi All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2016 Matthew Habib Emadi All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE ROYAL PRIEST: PSALM 110 IN BIBLICAL- THEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Matthew Habib Emadi May 2016 APPROVAL SHEET THE ROYAL PRIEST: PSALM 110 IN BIBLICAL- THEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE Matthew Habib Emadi Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ James M. Hamilton (Chair) __________________________________________ Peter J. Gentry __________________________________________ Brian J. Vickers Date______________________________ To my wife, Brittany, who is wonderfully patient, encouraging, faithful, and loving To our children, Elijah, Jeremiah, Aliyah, and Josiah, may you be as a kingdom and priests to our God (Rev 5:10) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................ ix LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ xii PREFACE ........................................................................................................................ xiii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

Heavenly Priesthood in the Apocalypse of Abraham

HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM The Apocalypse of Abraham is a vital source for understanding both Jewish apocalypticism and mysticism. Written anonymously soon after the destruction of the Second Jerusalem Temple, the text envisions heaven as the true place of worship and depicts Abraham as an initiate of the celestial priesthood. Andrei A. Orlov focuses on the central rite of the Abraham story – the scapegoat ritual that receives a striking eschatological reinterpretation in the text. He demonstrates that the development of the sacerdotal traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham, along with a cluster of Jewish mystical motifs, represents an important transition from Jewish apocalypticism to the symbols of early Jewish mysticism. In this way, Orlov offers unique insight into the complex world of the Jewish sacerdotal debates in the early centuries of the Common Era. The book will be of interest to scholars of early Judaism and Christianity, Old Testament studies, and Jewish mysticism and magic. ANDREI A. ORLOV is Professor of Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity at Marquette University. His recent publications include Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Selected Studies in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Concealed Writings: Jewish Mysticism in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2011), and Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology (2011). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139856430 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2013 HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM ANDREI A. ORLOV Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. -

1 When Your Enemies Are Too Many to Count Psalm 3 Introduction

1 When Your Enemies Are Too Many To Count Psalm 3 Introduction: 1) In life we should not be surprised when we are forced to fight, when we are faced with battles we cannot avoid. 2) One of life’s greatest disappointments and heartbreaks is to be in a foxhole, receiving enemy fire, only to feel a burning sharp pain in the back, to turn and see that someone you were certain was a friend, is actually the enemy who has just stabbed you in the back in cruel betrayal. 3) This no doubt is what David felt when he was betrayed by his own son, Absalom. (2 Sam. 15-18). 4) What should we do when all seems lost? Trust in the Lord and call out to Him in confidence that He will deliver us. I. Share Your Problem with God 3:1-2 Psalm 3 is the first Psalm with a superscription providing some information about its context and occasion for writing. It is a psalm of lament and it is the natural extension of Psalms 1 & 2. Interestingly, the promise of Psalm 2:12 is tragically fulfilled in the death of Absalom as recorded in 2 Sam. 18:14-15. 1) Tell the Lord What They Do 3:1 • Lord, how (amazement at the turn of events) they have increased who trouble me. Many…Many (vr 2). 2) Tell the Lord What They Say 2:2 • David’s adversaries are active (v.1) and they are accusing (v.2). • V.2 ends with “Selah,” as does vs. -

David's Elite Warriors and Their Exploits in the Books of Samuel And

The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures ISSN 1203–1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI, and BiBIL. Their abstracts appear in Reli- gious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by Library and Archives Canada and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by Library and Archives Canada (for a direct link, click here). Volume 11, Article 5 MOSHE GARSIEL, DAVID’S ELITE WARRIORS AND THEIR EXPLOITS IN THE BOOKS OF SAMUEL AND CHRONICLES 2 JOURNAL OF HEBREW SCRIPTURES DAVID’S ELITE WARRIORS AND THEIR EXPLOITS IN THE BOOKS OF SAMUEL AND CHRONICLES MOSHE GARSIEL BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY INTRODUCTION In this article,1 I intend to elaborate and update my previous publi- cations dealing with King David’s heroes and their exploits as rec- orded and recounted in the book of Samuel and repeated—with considerable changes—in the book of Chronicles.2 In Samuel, most of the information is included in the last part of the book (2 Sam 21–24), defined by previous scholars as an “Appendix.”3 To- day, several scholars have reservations about such a definition and replace it with “epilogue” or “conclusion,” inasmuch as these four chapters contain links among themselves as well as with the main part of the book.4 In any event, according to my recent research, 1 This article was inspired by my paper delivered at a conference on “The Shaping of the Historical Memory and Consciousness in the Book of Chronicles” that took place in the spring of 2010 at Bar-Ilan University. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

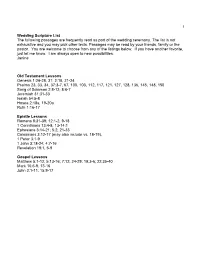

1 Wedding Scripture List the Following Passages Are Frequently Read As

1 Wedding Scripture List The following passages are frequently read as part of the wedding ceremony. The list is not exhaustive and you may pick other texts. Passages may be read by your friends, family or the pastor. You are welcome to choose from any of the listings below. If you have another favorite, just let me know. I am always open to new possibilities. Janine Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31; 2:18, 21-24 Psalms 23, 33, 34, 37:3-7, 67, 100, 103, 112, 117, 121, 127, 128, 136, 145, 148, 150 Song of Solomon 2:8-13; 8:6-7 Jeremiah 31:31-33 Isaiah 54:5-8 Hosea 2:18a, 19-20a Ruth 1:16-17 Epistle Lessons Romans 8:31-39; 12:1-2, 9-18 1 Corinthians 13:4-8, 13-14:1 Ephesians 3:14-21; 5:2, 21-33 Colossians 3:12-17 (may also include vs. 18-19). 1 Peter 3:1-9 1 John 3:18-24; 4:7-16 Revelation 19:1, 5-9 Gospel Lessons Matthew 5:1-12; 5:13-16; 7:12, 24-29; 19:3-6; 22:35-40 Mark 10:6-9, 13-16 John 2:1-11; 15:9-17 2 Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31 Then God said, "Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth." So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.