A Conversation with Jeannette Armstrong Prem Kumari Srivastava

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beginnings of Contemporary Aboriginal Literature in Canada 1967-1972: Part One1

H ARTMUT L UTZ The Beginnings of Contemporary Aboriginal Literature in Canada 1967-1972: Part One1 _____________________ Zusammenfassung Die Feiern zum hundertjährigen Jubiläum des Staates Kanada im Jahre 1967 boten zwei indianischen Künstlern Gelegenheit, Auszüge ihrer Literatur dem nationalen Publi- kum vorzustellen. Erst 1961 bzw. 1962 waren Erste Nationen und Inuit zu wahlberechtig- ten Bürgern Kanadas geworden, doch innerhalb des anglokanadischen Kulturnationa- lismus blieben ihre Stimmen bis in die 1980er Jahre ungehört. 1967 markiert somit zwar einen Beginn, bedeutete jedoch noch keinen Durchbruch. In Werken kanonisierter anglokanadischer Autorinnen und Autoren jener Jahre sind indigene Figuren überwie- gend Projektionsflächen ohne Subjektcharakter. Der Erfolg indianischer Literatur in den USA (1969 Pulitzer-Preis an N. Scott Momaday) hatte keine Auswirkungen auf die litera- rische Szene in Kanada, doch änderte sich nach Bürgerrechts-, Hippie- und Anti- Vietnamkriegsbewegung allmählich auch hier das kulturelle Klima. Von nicht-indigenen Herausgebern edierte Sammlungen „indianischer Märchen und Fabeln“ bleiben in den 1960ern zumeist von unreflektierter kolonialistischer Hybris geprägt, wogegen erste Gemeinschaftsarbeiten von indigenen und nicht-indigenen Autoren Teile der oralen Traditionen indigener Völker Kanadas „unzensiert“ präsentierten. Damit bereiteten sie allmählich das kanadische Lesepublikum auf die Veröffentlichung indigener Texte in modernen literarischen Gattungen vor. Résumé À l’occasion des festivités entourant le centenaire du Canada, en 1967, deux artistes autochtones purent présenter des extraits de leur littérature au public national. En 1961, les membres des Premières Nations avaient obtenu le droit de vote en tant que citoyens canadiens (pour les Inuits, en 1962 seulement), mais au sein de la culture nationale anglo-canadienne, leur voix ne fut guère entendue jusqu’aux années 1980. -

Aboriginal Literatures in Canada: a Teacher's Resource Guide

Aboriginal Literatures in Canada A Teacher’s Resource Guide Renate Eigenbrod, Georgina Kakegamic and Josias Fiddler Acknowledgments We want to thank all the people who were willing to contribute to this resource through interviews. Further we wish to acknowledge the help of Peter Hill from the Six Nations Polytechnic; Jim Hollander, Curriculum Coordinator for the Ojibway and Cree Cultural Centre; Patrick Johnson, Director of the Mi’kmaq Resource Centre; Rainford Cornish, librarian at the Sandy Lake high school; Sara Carswell, a student at Acadia University who transcribed the interviews; and the Department of English at Acadia University which provided office facilities for the last stage of this project. The Curriculum Services Canada Foundation provided financial support to the writers of this resource through its Grants Program for Teachers. Preface Renate Eigenbrod has been teaching Aboriginal literatures at the postsecondary level (mainly at Lakehead University, Thunder Bay) since 1986 and became increasingly concerned about the lack of knowledge of these literatures among her Native and non- Native students. With very few exceptions, English curricula in secondary schools in Ontario do not include First Nations literatures and although students may take course offerings in Native Studies, these works could also be part of the English courses so that students can learn about First Nations voices. When Eigenbrod’s teaching brought her to the Sandy Lake Reserve in Northwest Ontario, she decided, together with two Anishnaabe teachers, to create a Resource Guide, which would encourage English high school teachers across the country to include Aboriginal literatures in their courses. The writing for this Resource Guide is sustained by Eigenbrod’s work with Aboriginal students, writers, artists, and community workers over many years and, in particular, on the Sandy Lake Reserve with the high school teachers at the Thomas Fiddler Memorial High School, Georgina Kakegamic and Josias Fiddler. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT TITEL DER DIPLOMARBEIT “The Politics of Storytelling”: Reflections on Native Activism and the Quest for Identity in First Nations Literature: Jeannette Armstrong’s Slash, Thomas King’s Medicine River, and Eden Robinson’s Monkey Beach. VERFASSERIN Agnes Zinöcker ANGESTREBTER AKADEMISCHER GRAD Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, im Mai 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuer: o.Univ.-Prof. Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz Acknowledgements To begin with, I owe a debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz. He supported me in stressful times and patiently helped me to sort out my ideas about and reflections on Canadian literature. He introducing me to the vast field of First Nations literature, shared his insights and provided me with his advice and encouragements to develop the skills necessary for literary analysis. I am further indebted to express thanks to the ‘DLE Forschungsservice und Internationale Beziehungen’, who helped me complete my degree by attributing some funding to do research at the University of Victoria, British Columbia. I also wish to address special thanks to Prof. Misao Dean from the University of Victoria for letting me join some inspiring discussions in her ‘Core Seminar on Literatures of the West Coast’, which gave me the opportunity to exchange ideas with other students working in the field of Canadian literature. Lastly, I warmly thank my parents Dr. Hubert and Anna Zinöcker for their devoted emotional support and advice, and for sharing their knowledge and experience with me throughout my education. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Whispering in Shadows by Jeannette Armstrong Whispering in Shadows by Jeannette Armstrong

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Whispering in Shadows by Jeannette Armstrong Whispering in Shadows by Jeannette Armstrong. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #615b9ed0-cf80-11eb-8ca5-1fc2b1a7e9a7 VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Thu, 17 Jun 2021 15:26:26 GMT. ARMSTRONG, Jeannette. Nationality: Canadian (Okanagan). Born: Penticton (Okanagan) Indian Reservation, British Columbia, Canada, 1948. Education: Okanagan College; University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, B.F.A. Career: Since 1989 director, En'owkin School of International Writing, Okanagan, British Columbia. Publications. Novels. Slash. Penticton, British Columbia, Theytus, 1987; revised edition, 1998. Whispering in Shadows. Penticton, British Columbia, Theytus Books, 1999. Poetry. Breathtracks. Penticton, British Columbia, Theytus, 1991. Other. Enwhisteetkwa; Walk in Water (for children). Penticton, BritishColumbia, Theytus, 1982. Neekna and Chemai (for children), illustrated by Barbara Marchand. Penticton, British Columbia, Theytus, 1984. The Native Creative Process: A Collaborative Discourse , with Douglas Cardinal. Penticton, British Columbia, Theytus, 1992. We Get Our Living Like Milk from the Land: Okanagan Tribal History Book. Penticton, British Columbia, Theytus, 1993. Contributor, Speaking for the Generations: Native Writers on Writing , edited by Simon J. Ortiz. Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 1998. Contributor, Native North America: Critical and Cultural Perspectives: Essays , edited by Patricia Monture-Angus and Renee Hulan. Chicago, LPC Group, 1999. Critical Studies: Momaday, Vizenor, Armstrong: Conversations on American Indian Writing by Hartwig Isernhagen. -

University of Alberta the Im/Possibility of Recovery in Native North

University of Alberta The Im/possibility of Recovery in Native North American Literatures by Nancy Lynn Van Styvendale A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Nancy Lynn Van Styvendale Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Teresa Zackodnik, English and Film Studies Daphne Read, English and Film Studies Stephen Slemon, English and Film Studies Chris Andersen, Native Studies Shari Huhndorf, Ethnic Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies, University of Oregon Dedication To Aloys Neil Mark Fleischmann, for love, cats, dinners and questions, always the questions. Abstract Recovery is a ubiquitous theme in Native North American literature, as well as a repeated topic in the criticism on this literature, but the particulars of its meaning, mechanics, and ideological implications have yet to be explored by critics in any detail. -

Jeannette Armstrong

Jeannette Armstrong Biography Jeannette Armstrong, an Okanagan Indian, was born in 1948 and grew up on the Penticton Indian Reserve in British Columbia. Armstrong is the first Native woman novelist from Canada. Interestingly, she is also the grand niece of Hum-Ishu-Ma (Mourning Dove, b. 1927), the first Native American woman novelist. While growing up on the Pentic- ton Indian Reserve, Armstrong received a traditional education from Okanagan Elders and her family. From them, she learned the Okanagan Indian language. She is still a fluent speaker of the Okanagan language today. In 1978, she received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the University of Victoria. The same year, she received a Diploma of Fine Arts from Okanagan College. Her education was a precursor to many remarkable career achievements. Today, Armstrong is a writer, teacher, Quick Facts artist, sculptor, and activist for indigenous rights. * Born in 1948 At fifteen, Armstrong first discovered that she had a talent for and an * Okanagan interest in writing when her poem about John F. Kennedy was published Indian from in a local newspaper. Since then, her writing has helped reveal truths Canada about herself and her people. She says, “The process of writing as a Native person has been a healing one for me because I’ve uncovered the * Novelist, poet, fact that I’m not a savage, not dirty and ugly and not less because I have and indigenous brown skin, or a Native philosophy. “ She is proud of her Okanagan civil rights heritage. However, she knows that it is difficult for Indian people to be activist proud of their heritage while living in a society focused on European philosophies and ideals. -

Reading Native Literature from a Traditional Indigenous Perspective: Contemporary Novels in a Windigo Society a T Hesis Presente

Reading Native Literature from a Traditional Indigenous Perspective: Contemporary Novels in a Windigo Society A T hesis Presented to the Department of English Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario In partial fulf illment of the iequirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Peter Rasevych February 2001 0 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaON K1AON4 Ottawa ON KI A ûN4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Librq of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microforin, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d' auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otheMise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABST RACT In this thesis I explore three novels by Aboriginal authors, using a perspective that evolves from traditional Anishnabe teachings about the "Windigo" character. In the Introduction, I elaborate upon the reasons why an interdisciplinary study is necessary for the advancernent of Aboriginal education. In Chapter One, "Literary Colonizationln I formulate an Aboriginal literary criticism through "inside" perspectives of Aboriginal social reality and comrnunity. -

Indigenous Women Literature Resistance in Jeannette Arms Nous

PEOPLE’S AND DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF DJILLALI LIABES SIDI BEL ABBES FACULTY OF LETTERS, LANGUAGES AND ARTS Department of English Indigenous Women Literature Between Cultural Genocide and Resistance in Jeannette Armstrong’s Whispering in Shadows Dissertation Submitted to the Department of English in Partial Fulfillment For the Degree of Magister in Post-Colonial Women Literature Written in English Submitted by: Maachou KADDOUR Supervised by: Prof.Mohamed Yamin BOULENOUAR Board of Examiners: - President: Prof. Fewzia BEDJAOUI University of Sidi Bel Abbes - Supervisor: Prof .Mohamed Yamin BOULENOUAR University of Sidi Bel Abbes- -Examiner: Dr. Mohamed GRAZIB University of Saida- -Examiner: Dr. Djamel BENADLA University of Saida Academic Year: 2016-2017 DEDICATIONS I dedicate this modest work to the soul of my father who passed away two years ago. ….. to my darling mother who taught me how to be patient in hard moments . ….. to all the people around me with whom I share respect, love and hope. …..to my wife, my brothers, sisters, and my nephews. ….to my supervisor Prof. Boulenouar Mohamed Yamin for his help and patience, in spite the hard moments he faces owing to his son’s health problems. I hope from Allah a quick recovery for him. ….to Prof. Bedjaoui Fewzia for her endless help, guidance and support. …..to my classmates of post graduate studies; Abdelnacer, Noureddine, Amina, Nadia and Djamila. I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I wish to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Boulenouar Mohamed Yamin for his help, assistance and guidance, my sincere thanks to my teacher; professor Bedjaoui Fewzia who was abundantly helpful and offered assistance, support, practical guidance and careful instructions. -

Introduction to Jeannette Armstrong Chapter -1

(r CHAPTER -1 INTRODUCTION TO JEANNETTE ARMSTRONG CHAPTER -1 INTRODUCTION TO JEANNETTE ARMSTRONG 1.1 THE CANADIAN NOVEL : A BRIEF SURVEY The Canadian novel includes four phases of its development. The first phase of the Canadian novel, which runs parallel with that of the British novel during the Victorian age, paves a path for the later mature Canadian novel written in modern age. Literary historians and critics believe that Frances Brookes’ The History of Emily Montague (1769) is the first Canadian novel, which was published in London. Though the novel gives little encouragement, it leads the way towards English Canadian fiction. This novel deals with the North American life, giving it an identity of its own. St. Ursulas Convent or The Nun of Canada (1824) by Julia Catherine Beckwith Hart is the first novel published in Canada and written by a native born writer. Some good works were brought forth by the trend of publishing outside Canada. Anisur Rahman has rightly pointed out : “the fashion of publishing outside Canada caught the imagination of the novelists but it created a reading public in Canada as well.” (1996 : 57) 2 Many outside influences on Canadian novelists are to be noted during this phase, the most important being Sir Walter Scott. Apart from this, many of the Canadian novelists were also influenced by the land. It is essential to examine the emergence and development of the novel in Canada. The second phase of the Canadian novel throws light on new challenges and new hopes experienced by Canada at the beginning of the twentieth century. -

Cultural Expression

208 B.C.PART First Nations FOU StudiesR Cultural Expression Culture . is dynamic, grounded in ethics and values that provide a practical guide and a moral compass enabling people to adapt to changing circumstances. The traditional wisdom at the core of this culture may transcend time and circumstance, but the way it is applied differs from one situation to another. It is the role of the family—that is, the extended network of kin and community—to demonstrate how traditional teachings are applied in everyday life.—1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. 1 ulture is a guide and a moral compass, as Images are often the most distinctive way in which the Report of the Royal Commission on Abo- an individual or a group expresses culture to the C riginal Peoples states. Aboriginal cultures outside world. The visual arts are explored in Chapter are rooted in an enduring relationship with the 16, including a look at the traditional art forms of the land; beliefs and values held by Aboriginal peoples interior and the coastal First Nations, and the impact reflect their unique world views, in which all of life that governmental policies had on their execution. is seen holistically. This is the way people expressed Additionally this chapter discusses the contemporary their cultures in the past. The elements of what we resurgence of the visual arts, which plays a role in classify today as “the Arts” were part of the whole rebuilding the identity of First Nations communities cultural fabric, integrating social, political, spiritual, and also offers significant career opportunities for and economic realms. -

School Failed Coyote, So Fox Made a New School: Indigenous Okanagan Knowledge Transforms Educational Pedagogy

SCHOOL FAILED COYOTE, SO FOX MADE A NEW SCHOOL: INDIGENOUS OKANAGAN KNOWLEDGE TRANSFORMS EDUCATIONAL PEDAGOGY by William Alexander Cohen M. Ed., Simon Fraser University, 1999 B. A. & Sc., University of Lethbridge, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Educational Studies) The University of British Columbia (Vancouver) November, 2010 © William Alexander Cohen, 2010 ABSTRACT This project examines how Indigenous Okanagan knowledge embedded in traditional stories, life histories and people‘s practices, responsibilities and relationships are relevant and applicable to current and future Okanagan people‘s educational and cultural aspirations. Okanagan language proficiency, cultural and territorial knowledge and practice, provincial curriculum and world knowledge are all important elements in creating Okanagan identity. The focus of this thesis is to identify, understand and theorise the transforming potential of Okanagan pedagogy through the development of an Okanagan cultural and language immersion school where language and cultural knowledge recovery are key elements, and express a new and current understanding, through a Sqilxw- Okanagan, children centred, extended family pedagogical approach and curriculum structure for current application in schooling projects and communities. Indigenous and world knowledge that improves, complements, and is compatible with evolving Okanagan knowledge and practice is included to generate an interconnected web; a convergence that may be useful in Okanagan, Indigenous and world educational contexts. ii PREFACE My research is informed by Sqilxw-Okanagan epistemology which suggests knowledge is a continuously evolving web of relationships. By gathering bits of old and current knowledge, engaging in dialogue, action, and reflection, a new understanding emerges. -

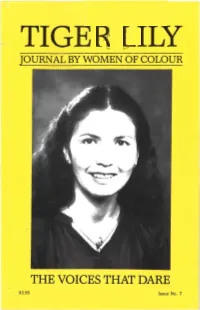

The Voices That Dare

v ....... THE VOICES THAT DARE $3.95 Issue No. 7 THE VOICES THAT DARE ________ TIGER LILY ________ Journal by Women of Colour Publisher I Editor-in-Chief Ann Wallace Editorial Committee Zanana Akande, Susan Korah, Monicc;i Riutort, Karen 'fyrell Contributing Writers Zanana Akande, Jeannette Armstrong, Ramabai Espinet, Alice French, Z. Nelly Martinez, Arun Mukherjee, Angela Lawrence, Sonya C. Wall, Ivy Williams Production Duo Productions Ltd. Business Manager Gloria Fallick Advisory Board Gay Allison, Glace Lawrence, Ana Mendez, Arun Mukherjee, Beverly Salmon, Leslie Sanders, Anita Shilton Photo Credits Cover Photo - Hugo Redivo Tiger Lily journal is published by Earthtone Women's Magazine (Ontario) Inc. P.O. Box 756, Stratford, Ontario NSA 4AO. ISSN 0-832-9199-07. Authors retain copyright, 1990. All Rights reserved. Unsolicited manuscripts or artwork should include a SASE. Printed and Bound in Canada. --------CONTENTS ________ 4 From the Publisher's Desk PROFILE: 6 Jeannette Armstrong: A Native Writer and Administrator Sonya C. Wall POETRY: 10 Bre9th Tracks Jeannette Armstrong INUIT BIOGRAPHY: 18 My Name is Masak Alice French ESSAY: 23 The Third World in the Dominant Western Cinema Arun Mukherjee EDUCATION 32 Fran Endicott, Board Trustee Zanana Akande FICTION: 35 Because I Could Not Stop for Death Ramabai Espinet HEALTH: 40 After the Door Has Been Opened Ivy Williams ESSAY: 49 Isabel Allende's - The House of the Spirits The Emergence of a Feminine Space Z. Nelly Martinez BOOK REVIEW: 58 Charting the Journey: Writings by Black and Third World Women Angela Lawrence ____ FROM THE PUBLISHER'S DESK ____ The Voices That Dare The role of the storyteller is critical in all societies.