Aboriginal Literatures in Canada: a Teacher's Resource Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beginnings of Contemporary Aboriginal Literature in Canada 1967-1972: Part One1

H ARTMUT L UTZ The Beginnings of Contemporary Aboriginal Literature in Canada 1967-1972: Part One1 _____________________ Zusammenfassung Die Feiern zum hundertjährigen Jubiläum des Staates Kanada im Jahre 1967 boten zwei indianischen Künstlern Gelegenheit, Auszüge ihrer Literatur dem nationalen Publi- kum vorzustellen. Erst 1961 bzw. 1962 waren Erste Nationen und Inuit zu wahlberechtig- ten Bürgern Kanadas geworden, doch innerhalb des anglokanadischen Kulturnationa- lismus blieben ihre Stimmen bis in die 1980er Jahre ungehört. 1967 markiert somit zwar einen Beginn, bedeutete jedoch noch keinen Durchbruch. In Werken kanonisierter anglokanadischer Autorinnen und Autoren jener Jahre sind indigene Figuren überwie- gend Projektionsflächen ohne Subjektcharakter. Der Erfolg indianischer Literatur in den USA (1969 Pulitzer-Preis an N. Scott Momaday) hatte keine Auswirkungen auf die litera- rische Szene in Kanada, doch änderte sich nach Bürgerrechts-, Hippie- und Anti- Vietnamkriegsbewegung allmählich auch hier das kulturelle Klima. Von nicht-indigenen Herausgebern edierte Sammlungen „indianischer Märchen und Fabeln“ bleiben in den 1960ern zumeist von unreflektierter kolonialistischer Hybris geprägt, wogegen erste Gemeinschaftsarbeiten von indigenen und nicht-indigenen Autoren Teile der oralen Traditionen indigener Völker Kanadas „unzensiert“ präsentierten. Damit bereiteten sie allmählich das kanadische Lesepublikum auf die Veröffentlichung indigener Texte in modernen literarischen Gattungen vor. Résumé À l’occasion des festivités entourant le centenaire du Canada, en 1967, deux artistes autochtones purent présenter des extraits de leur littérature au public national. En 1961, les membres des Premières Nations avaient obtenu le droit de vote en tant que citoyens canadiens (pour les Inuits, en 1962 seulement), mais au sein de la culture nationale anglo-canadienne, leur voix ne fut guère entendue jusqu’aux années 1980. -

1.1 Passamaquoddy, They Speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (Also Known As Maliseet- Passamaquoddy

1.1 Passamaquoddy, they speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (also known as Maliseet- Passamaquoddy. It is an endangered language from the Algonquian language family (1) 1.2 Pqm (2) 1.3 45.3,-66.656 (3) 1.4 The Passamaquoddy tribe belonged to the loose confederation of eastern American Indians known as the Wabanaki Alliance, together with the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Abenaki, and Penobscot tribes. Today most Passamaquoddy people live in Maine, in two communities along the Passamaquoddy Bay that bears their name. However, there is also a band of a few hundred Passamaquoddy people in New Brunswick. The French referred to both the Passamaquoddy and their Maliseet kinfolk by the same name, "Etchimins." They were closely related peoples who shared a common language, but the two tribes have always considered themselves politically independent. Smallpox and other European diseases took a heavy toll on the Passamaquoddy tribe, which was reduced from at least 20,000 people to no more than 4000. Pressured by European and Iroquois aggression, the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy banded together with their neighbors the Abenakis, Penobscots, and Micmacs into the short-lived but formidable Wabanaki Confederacy. This confederacy was no more than a loose alliance, however, and neither the Maliseet nor the Passamaquoddy nation ever gave up their sovereignty. Today the Passamaquoddy live primarily in the United States and the Maliseet in Canada, but the distinction between the two is not imposed by those governments--the two tribes have always been politically distinct entities. (4) 1.5 After working with the French and joining the Abnaki confederation against the English, many converted to Catholicism. -

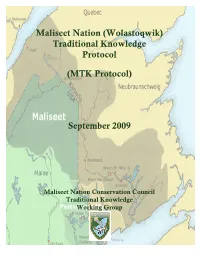

Traditional Knowledge Protocol

Maliseet Nation (Wolastoqwik) Traditional Knowledge Protocol (MTK Protocol) September 2009 Maliseet Nation Conservation Council Traditional Knowledge Working Group Table of Contents Foreword …………………………………………………………………………… i 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 1 2.0 Definitions …………………………………………………………………… 2 3.0 Interpretation ………………………………………………………………… 3 4.0 MTK Methodology …………………………………………………………… 4 I Project Planning ………………………………………………………… 5 II Delivery and Implementation ……………………………………………… 6 III Finalizing Report and Disclosure ………………………………………… 7 5.0 Amendments …………………………………………………………………… 7 Appendices …………………………………………………………………………… 8 Maliseet Leadership Proclamation / Resolution …………………………… 9 Draft Maliseet Ethics Guidelines ……………………………………… 10 Foreword Development of the Maliseet Nation Traditional Knowledge (MTK) Protocol highlights the recognition of the importance of Aboriginal traditional knowledge in relation to the environmental issues facing Maliseet traditional territory, the Saint John River (Wolustok) watershed1. The protection of such knowledge has been identified by the Maliseet Chiefs as a crucial component for future relations with non-Aboriginals, as increasing development activity continues to cause concern for all parties on the best way to proceed, in the spirit of cooperation and with due respect for Maliseet Aboriginal and Treaty rights2. The protocol also addresses past problems with research projects such as lack of consultation of Maliseet people, lack of meaningful community involvement, lack of benefit from research, lack of informed consent, lack of community ownership of data (including analysis, interpretation, recording or access), and lack of respect of our culture and beliefs by outside researchers. Initiated by the Maliseet Nation Conservation Council and produced through the combined efforts of informed Maliseet Elders, leaders, committees and grassroots volunteers, this protocol identifies the methods developed by the Maliseet Nation for the proper and thorough collection and use of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). -

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations February 2017 Nicole Friederichs Amy Van Zyl-Chavarro Kate Bertino Commissioned by the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission Contact Information: 120 Tremont Street Nicole Friederichs Boston, MA 02108 Practitioner-in-Residence Tel.: 1-617-305-1682 Indigenous Peoples Rights Clinic Fax: 1-617-573-8100 Suffolk University Law School Email: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission (MITSC) is honored to offer this thorough review of the crafting of the Federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, 25 U.S.C. §§ 1721-1735. In June of 2014, the MITSC completed the Assessment of the Intergovernmental Saltwater Fisheries Conflict between Passamaquoddy and the State of Maine where the MITSC offered the following framework: The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, (MICSA), was passed in October of the same year [1980]. The MICSA gave federal permission for the [state Maine Implementing Act] (MIA) to take effect while retaining intact the federal trust relationship between the federally recognized tribes of Maine and the US Congress; and placed constraints on the implementation of the MIA. Of particular interest to the inquiry into the saltwater fishery conflict between the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the State of Maine are the following provisions of the federal act: 1. MICSA (25 U.S.C. § 1735 (a)) provides that “In the event a conflict of interpretation between the provisions of the Maine Implementing Act and this Act should emerge, the provisions of this Act shall govern.” The provisions of the federal MICSA thus override the MIA provisions when there is a conflict between the two. -

Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing

UNIVERSITY PRESS <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu> CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb> Purdue University Press ©Purdue University The Library Series of the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access quarterly in the humanities and the social sciences CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture publishes scholarship in the humanities and social sciences following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the CLCWeb Library Series are 1) articles, 2) books, 3) bibliographies, 4) resources, and 5) documents. Contact: <[email protected]> Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweblibrary/canadianethnicbibliography> Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, Asma Sayed, and Domenic A. Beneventi 1) literary histories and bibliographies of canadian ethnic minority writing 2) work on canadian ethnic minority writing This selected bibliography is compiled according to the following criteria: 1) Only English- and French-language works are included; however, it should be noted that there exists a substantial corpus of studies in a number Canada's ethnic minority languages; 2) Critical works about the literatures of Canada's First Nations are not included following the frequently expressed opinion that Canadian First Nations literatures should not be categorized within Canadian "Ethnic" writing but as a separate corpus; 3) Literary criticism as well as theoretical texts are included; 4) Critical texts on works of authors writing in English and French but usually viewed or which could be considered as "Ethnic" authors (i.e., immigré[e]/exile individuals whose works contain Canadian "Ethnic" perspectives) are included; 5) Some works dealing with US or Anglophone-American Ethnic Minority Writing with Canadian perspectives are included; 6) M.A. -

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story Written by Cindy Blackstock Illustrated by Amanda Strong Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N) zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee- chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc -

Ontario Curriculum, Grades 11 and 12 English

Ministry of Education The Ontario Curriculum Grades 11 and 12 English 2000 Contents Introduction . 2 The Place of English in the Curriculum . 2 The Program in English . 4 Overview . 4 Teaching Approaches . 7 Curriculum Expectations . 7 Strands . 8 Compulsory Courses . 12 English, Grade 11, University Preparation (ENG3U) . 13 English, Grade 11, College Preparation (ENG3C) . 22 English, Grade 11,Workplace Preparation (ENG3E) . 31 English, Grade 12, University Preparation (ENG4U) . 40 English, Grade 12, College Preparation (ENG4C) . 49 English, Grade 12,Workplace Preparation (ENG4E) . 58 Optional Courses . 67 Canadian Literature, Grade 11, University/College Preparation (ETC3M) . 68 Literacy Skills: Reading and Writing, Grade 11, Open (ELS3O) . 72 Media Studies, Grade 11, Open (EMS3O) . 78 Presentation and Speaking Skills, Grade 11, Open (EPS3O) . 84 Studies in Literature, Grade 12, University Preparation (ETS4U) . 89 The Writer’s Craft, Grade 12, University Preparation (EWC4U) . 93 Studies in Literature, Grade 12, College Preparation (ETS4C) . 97 The Writer’s Craft, Grade 12, College Preparation (EWC4C) . 101 Communication in the World of Business and Technology,Grade 12, Open (EBT4O) . 105 Some Considerations for Program Planning in English . 110 The Achievement Chart for English . 112 This publication is available on the Ministry of Education’s website at http://www.edu.gov.on.ca. 2 Introduction The Ontario Curriculum, Grades 11 and 12: English, 2000 will be implemented in Ontario sec- ondary schools starting in September 2001 for students -

AVAILABLE from Jamaica Plains, MA 02130

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 226 893 RC 013 868 AUTHOR Braber, Lee; Dean, Jacquelyn M. TITLE A Teacher Training Manual on NativeAmericans: The Wabanakis. INSTITUTION Boston Indian Council, Inc., JamaicaPlain, MA. SPONS AGENCY Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (ED), Washington, D.C. Ethnic Heritage Studies Program. PUB DATE 82 NOTE 74p.; For related document, see RC 013 869. AVAILABLE FROMBoston Indian Council, 105 South Huntington Ave., Jamaica Plains, MA 02130 ($8.00 includes postage and handling, $105.25 for 25 copies). PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indian Education; *Cultural Awareness; Elementary Secondary Education; *Enrichment Activities; Legends; *Life Style; Resource Materials; Teacher Qualifications;Tribes; *Urban American Indians IDENTIFIERS American Indian History; Boston Indian Council MA; Maliseet (Tribe); Micmac (Tribe); Passamaquoddy (Tribe); Penobscot (Tribe); Seasons; *Teacher Awareness; *Wabanaki Confederacy ABSTRACT The illustrated boóklet, developed by theWabanaki Ethnic Heritage Curriculum Development Project,is written for the Indian and non-Indian educator as a basic primer onthe Wabanaki tribal lifestyle. The Wabanaki Confederacy is made upof the following tribes: Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy,and Penobscot. Advocating a positive approach to teaching aboutNative Americans in general and highlighting the Wabanaki wayof life, past and present, the booklet is divided into four parts: anintroduction, Native American awareness, the Wabanakis, and appendices.Within these four parts, the teacher is given a brief look atNative American education, traditional legends, the lifestyleof the Wabanaki, the Confederacy, seasonal activities, and thechanges that occured when the Europeans came. An awareness of theWabanakis in Boston and the role of the Boston Indian Council, Inc., areemphasized. -

Aboriginal Place Names Rimouski: (Quebec) This Is a Word of Mi’Kmaq Or Contribute to a Rich Tapestry

Pamphlet # 24 Ontario: This Huron name, first applied to the lake, the Chipewyan people, and means "pointed skins," a may be a corruption of onitariio, meaning "beautiful Cree reference to the way the Chipewyan prepared lake," or kanadario, which translates as "sparkling" or beaver pelts. Aboriginal Peoples Contributions to "beautiful" water. Place Names in Canada Medicine Hat: (Alberta) This is a translation of the Quebec: Aboriginal peoples first used the name Blackfoot word, saamis, meaning "headdress of a 1 Provinces and Territories "kebek" for the region around Québec City. It refers medicine man." According to one explanation, the to the Algonquin word for "narrow passage" or word describes a fight between the Cree and The map of Canada is a rich tapestry of place names "strait" to indicate the narrowing of the river at Cape Blackfoot, when a Cree medicine man lost his which reflect the diverse history and heritage of our Diamond. plumed hat in the river. nation. Many of the country's earliest place names draw on Aboriginal sources. Before the arrival of Yukon: This name belonged originally to the Yukon Wetaskiwin: (Alberta) This is an adaptation of the Europeans, First Nations and Inuit peoples gave river and is from a Loucheux (Dene) word, LoYu- Cree word wi-ta-ski-oo cha-ka-tin-ow, which can be names to places throughout the country to identify kun-ah, meaning "great river." translated as "place of peace" or "hill of peace." the land they knew so well and with which they had strong spiritual connections. For centuries, these Nunavut: This is the name of Canada's newest Saskatoon: (Saskatchewan) The name comes from names that described the natural features of the land, territory which came into being on April 1, 1999. -

Enhancing the Use of Regional Literature in Atlantic Canadian Schools

Partnership: the Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, vol. 7, no. 1 (2012) The Sea Stacks Project: Enhancing the Use of Regional Literature in Atlantic Canadian Schools Vivian Howard Associate Professor/Associate Dean (Academic) School of Information Management Dalhousie University [email protected] Abstract Research over the past two decades has amply demonstrated the importance of literature to the formation of both regional and national cultural identity, particularly in the face of mass market globalization of children's book publishing in the 21st century as well as the predominance of non-Canadian content from television, movies, books, magazines and internet media. However, Canadian children appear to have only very limited exposure to Canadian authors and illustrators. In Atlantic Canada, regional Atlantic Canadian authors and illustrators for children receive very limited critical attention, and resources for the study and teaching of Atlantic Canadian children's literature are few. Print and digital information sources on regional children's books, publishing, authors and illustrators are scattered and inconsistent in quality and currency. This research project directly addresses these key concerns by summarizing the findings of a survey of Atlantic Canadian teachers on their use of regional books. In response to survey findings, the paper concludes by describing the creation of the Sea Stacks Project: an authoritative, web-delivered information resource devoted to contemporary Atlantic Canadian literature for children and teens. Keywords library and information studies; services and resources for youth; children's literature The significance of Canadian children's literature for developing cultural awareness is documented by a growing body of research literature (Egoff and Saltman, 1999; Diakiw, 1997; Pantaleo, 2000; Baird, 2002; Reimer, 2008). -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Critical Canadiana

Critical Canadiana Jennifer Henderson In 1965, in the concluding essay to the first Literary History New World Myth: of Canada, Northrop Frye wrote that the question “Where is Postmodernism and here?” was the central preoccupation of Canadian culture. He Postcolonialism in equivocated as to the causes of this national condition of disori- Canadian Fiction By Marie Vautier entation, alternately suggesting historical, geographical, and cul- McGill-Queen’s tural explanations—the truncated history of a settler colony, the University Press, 1998 lack of a Western frontier in a country entered as if one were “be- ing silently swallowed by an alien continent” (217), a defensive The House of Difference: colonial “garrison mentality” (226)—explanations that were uni- Cultural Politics and National Identity in fied by their unexamined Eurocentrism. Frye’s thesis has since Canada proven to be an inexhaustible departure point for commentaries By Eva Mackey on Canadian literary criticism—as witnessed by this very essay, by Routledge, 1999 the title of one of the four books under review, as well as a recent issue of the journal Essays in Canadian Writing, organized around Writing a Politics of the question, “Where Is Here Now?” The question was first asked Perception: Memory, Holography, and Women at what many take to be the inaugural moment of the institution- Writers in Canada alization of CanLit, when the field began to be considered a cred- By Dawn Thompson ible area of research specialization.1 Since then, as one of the University of Toronto contributors to “Where Is Here Now?” observes, “Canadian liter- Press, 2000 ature as an area of study has become a rather staid inevitable in Here Is Queer: English departments” (Goldie 224).