The Wabanaki Indian Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.1 Passamaquoddy, They Speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (Also Known As Maliseet- Passamaquoddy

1.1 Passamaquoddy, they speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (also known as Maliseet- Passamaquoddy. It is an endangered language from the Algonquian language family (1) 1.2 Pqm (2) 1.3 45.3,-66.656 (3) 1.4 The Passamaquoddy tribe belonged to the loose confederation of eastern American Indians known as the Wabanaki Alliance, together with the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Abenaki, and Penobscot tribes. Today most Passamaquoddy people live in Maine, in two communities along the Passamaquoddy Bay that bears their name. However, there is also a band of a few hundred Passamaquoddy people in New Brunswick. The French referred to both the Passamaquoddy and their Maliseet kinfolk by the same name, "Etchimins." They were closely related peoples who shared a common language, but the two tribes have always considered themselves politically independent. Smallpox and other European diseases took a heavy toll on the Passamaquoddy tribe, which was reduced from at least 20,000 people to no more than 4000. Pressured by European and Iroquois aggression, the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy banded together with their neighbors the Abenakis, Penobscots, and Micmacs into the short-lived but formidable Wabanaki Confederacy. This confederacy was no more than a loose alliance, however, and neither the Maliseet nor the Passamaquoddy nation ever gave up their sovereignty. Today the Passamaquoddy live primarily in the United States and the Maliseet in Canada, but the distinction between the two is not imposed by those governments--the two tribes have always been politically distinct entities. (4) 1.5 After working with the French and joining the Abnaki confederation against the English, many converted to Catholicism. -

"I'm Glad to Hear That You Liked M Y Little Article": Letters Exchanged

"I'm glad to hear that you liked my little article": Letters Exchanged Between Frank T. Siebert and Fannie Hardy Eckstorm, 1938-1945 PAULEENA MACDOUGALL University of Maine Writing from his home at 127 Merbrook Lane, Merion Station, Pennsylvania, on 9 January 1938, Dr. Frank T. Siebert, Jr., penned the following: Dear Mrs. Eckstorm: Many thanks for your very nice letter. I am glad to hear that you liked my little article. I have several others, longer and of broader scope, in preparation, but they probably will not appear for some time to come. One of these is a volume of Penobscot linguistic texts, of which Dr. Speck and I are joint authors. The letter quoted above and others to follow offer a glimpse into the thoughts of two very different people who shared an interest in the Penobscot Indians: one, a woman of 73 years who had already published seven books and numerous articles at the time the two began correspond ing, the other a 26-year-old medical doctor. Siebert studied at Episcopal Academy, Haverford College, and received his M.D. at the University of Pennsylvania, where he made the acquaintance of anthropologist Frank Speck. The young doctor attended summer institutes in linguistics where he encountered Algonquianists such as Leonard Bloomfield, Edward Sapir and Mary Haas. His ability in the field of linguistics did not go unnoticed at the University of Pennsylvania, because Speck asked him to lecture in his anthropology class. Siebert visited the Penobscot Indian Reservation in 1932 for the first time and collected vocabulary and stories from Penobscot speakers thereafter on his summer vacations. -

A Report on Indian Township Passamaquoddy Tribal Lands In

A REPORT ON INDIAN TOWNSHIP PASSAMAQUODDY TRIBAL LANDS IN THE VICINITY OF PRINCETON, MAINE Anthony J. Kaliss 1971 Introduction to 1971 Printing Over two years have passed since I completed the research work for this report and during those years first one thing and ttan another prevented its final completion and printing. The main credit for the final preparation and printing goes to the Division of Indian Services of the Catholic Diocese of Portland and the American Civil Liberities Union of Maine. The Dioscese provided general assistance from its office staff headed by Louis Doyle and particular thanks is due to Erline Paul of Indian Island who did a really excellent job of typing more than 50 stencils of title abstracts, by their nature a real nuisance to type. The American Civil Liberities Union contrib uted greatly by undertaking to print the report Xtfhich will come to some 130 pages. Finally another excellent typist must be thanked and that is Edward Hinckley former Commissioner of Indian Affairs who also did up some 50 stencils It is my feeling that this report is more timely than ever. The Indian land problems have still not been resolved, but more and more concern is being expressed by Indians and non-Indians that something be done. Hopefully the appearance of this report at this time will help lead to some definite action whether in or out of the courts. Further research on Indian lands and trust funds remains to be done. The material, I believe, is available and it is my hope that this report will stimulate someone to undertake the necessary work. -

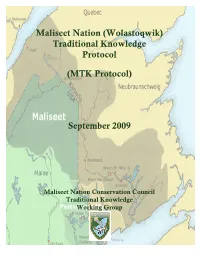

Traditional Knowledge Protocol

Maliseet Nation (Wolastoqwik) Traditional Knowledge Protocol (MTK Protocol) September 2009 Maliseet Nation Conservation Council Traditional Knowledge Working Group Table of Contents Foreword …………………………………………………………………………… i 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 1 2.0 Definitions …………………………………………………………………… 2 3.0 Interpretation ………………………………………………………………… 3 4.0 MTK Methodology …………………………………………………………… 4 I Project Planning ………………………………………………………… 5 II Delivery and Implementation ……………………………………………… 6 III Finalizing Report and Disclosure ………………………………………… 7 5.0 Amendments …………………………………………………………………… 7 Appendices …………………………………………………………………………… 8 Maliseet Leadership Proclamation / Resolution …………………………… 9 Draft Maliseet Ethics Guidelines ……………………………………… 10 Foreword Development of the Maliseet Nation Traditional Knowledge (MTK) Protocol highlights the recognition of the importance of Aboriginal traditional knowledge in relation to the environmental issues facing Maliseet traditional territory, the Saint John River (Wolustok) watershed1. The protection of such knowledge has been identified by the Maliseet Chiefs as a crucial component for future relations with non-Aboriginals, as increasing development activity continues to cause concern for all parties on the best way to proceed, in the spirit of cooperation and with due respect for Maliseet Aboriginal and Treaty rights2. The protocol also addresses past problems with research projects such as lack of consultation of Maliseet people, lack of meaningful community involvement, lack of benefit from research, lack of informed consent, lack of community ownership of data (including analysis, interpretation, recording or access), and lack of respect of our culture and beliefs by outside researchers. Initiated by the Maliseet Nation Conservation Council and produced through the combined efforts of informed Maliseet Elders, leaders, committees and grassroots volunteers, this protocol identifies the methods developed by the Maliseet Nation for the proper and thorough collection and use of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). -

The Morphology of Modern Western Abenaki

The Morphology of Modern Western Abenaki Jesse Beach ‘04 Honors Thesis Dartmouth College Program of Linguistics & Cognitive Science Primary Advisor: Prof. David Peterson Secondary Advisor: Prof. Lindsay Whaley May 17, 2004 Acknowledgements This project has commanded a considerable amount of my attention and time over the past year. The research has lead me not only into Algonquian linguistics, but has also introduced me to the world of Native American cultures. The history of the Abenaki people fascinated me as much as their language. I must extnd my fullest appreciate to my advisor David Peterson, who time and again proposed valuable reference suggestions and paths of analysis. The encouragement he offered was indispensable during the research and writing stages of this thesis. He also went meticulously through the initial drafts of this document offering poignant comments on content as well as style. My appreciation also goes to my secondary advisor Lindsay Whaley whose door is always open for a quick chat. His suggestions helped me broaden the focus of my research. Although I was ultimately unable to arrange the field research component of this thesis, the generosity of the Dean of Faculty’s Office and the Richter Memorial Trust Grant that I received from them assisted me in gaining a richer understanding of the current status of the Abenaki language. With the help of this grant, I was able to travel to Odanak, Quebec to meet the remaining speakers of Abenaki. From these conversations I was able to locate additional materials that aided me tremendously in my analysis. Many individuals have offered me assistance in one form or another throughout the unfolding of my research. -

A Brief History of the Passamaquoddy Indians

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Maine The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1977 A Brief History of the Passamaquoddy Indians Susan M. Stevens Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Revised 1/77 A BRIEF HISTORY Pamp 4401 of the c.l PASSAMAQUODDY INDIANS By Susan M. Stevens - 1972 The Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine are located today on two State Reservations about 50 miles apart. One is on Passamaquoddy Bay, near Eastport (Pleasant Point Reservation); the other is near Princeton, Maine in a woods and lake region (Indian Township Reservation). Populations vary with seasonal jobs, but Pleasant Point averages about 400-450 residents and Indian Township averages about 300- 350 residents. If all known Passamaquoddies both on and off the reservations were counted, they would number around 1300. The Passamaquoddy speak a language of the larger Algonkian stock, known as Passamaquoddy-Malecite. The Malecite of New Brunswick are their close relatives and speak a slightly different dialect. The Micmacs in Nova Scotia speak the next most related language, but the difference is great enough to cause difficulty in understanding. The Passamaquoddy were members at one time of the Wabanaki (or Abnaki) Confederacy, which included most of Maine, New Hampshire, and Maritime Indians. -

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations February 2017 Nicole Friederichs Amy Van Zyl-Chavarro Kate Bertino Commissioned by the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission Contact Information: 120 Tremont Street Nicole Friederichs Boston, MA 02108 Practitioner-in-Residence Tel.: 1-617-305-1682 Indigenous Peoples Rights Clinic Fax: 1-617-573-8100 Suffolk University Law School Email: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission (MITSC) is honored to offer this thorough review of the crafting of the Federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, 25 U.S.C. §§ 1721-1735. In June of 2014, the MITSC completed the Assessment of the Intergovernmental Saltwater Fisheries Conflict between Passamaquoddy and the State of Maine where the MITSC offered the following framework: The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, (MICSA), was passed in October of the same year [1980]. The MICSA gave federal permission for the [state Maine Implementing Act] (MIA) to take effect while retaining intact the federal trust relationship between the federally recognized tribes of Maine and the US Congress; and placed constraints on the implementation of the MIA. Of particular interest to the inquiry into the saltwater fishery conflict between the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the State of Maine are the following provisions of the federal act: 1. MICSA (25 U.S.C. § 1735 (a)) provides that “In the event a conflict of interpretation between the provisions of the Maine Implementing Act and this Act should emerge, the provisions of this Act shall govern.” The provisions of the federal MICSA thus override the MIA provisions when there is a conflict between the two. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story Written by Cindy Blackstock Illustrated by Amanda Strong Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N) zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee- chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc -

AVAILABLE from Jamaica Plains, MA 02130

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 226 893 RC 013 868 AUTHOR Braber, Lee; Dean, Jacquelyn M. TITLE A Teacher Training Manual on NativeAmericans: The Wabanakis. INSTITUTION Boston Indian Council, Inc., JamaicaPlain, MA. SPONS AGENCY Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (ED), Washington, D.C. Ethnic Heritage Studies Program. PUB DATE 82 NOTE 74p.; For related document, see RC 013 869. AVAILABLE FROMBoston Indian Council, 105 South Huntington Ave., Jamaica Plains, MA 02130 ($8.00 includes postage and handling, $105.25 for 25 copies). PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indian Education; *Cultural Awareness; Elementary Secondary Education; *Enrichment Activities; Legends; *Life Style; Resource Materials; Teacher Qualifications;Tribes; *Urban American Indians IDENTIFIERS American Indian History; Boston Indian Council MA; Maliseet (Tribe); Micmac (Tribe); Passamaquoddy (Tribe); Penobscot (Tribe); Seasons; *Teacher Awareness; *Wabanaki Confederacy ABSTRACT The illustrated boóklet, developed by theWabanaki Ethnic Heritage Curriculum Development Project,is written for the Indian and non-Indian educator as a basic primer onthe Wabanaki tribal lifestyle. The Wabanaki Confederacy is made upof the following tribes: Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy,and Penobscot. Advocating a positive approach to teaching aboutNative Americans in general and highlighting the Wabanaki wayof life, past and present, the booklet is divided into four parts: anintroduction, Native American awareness, the Wabanakis, and appendices.Within these four parts, the teacher is given a brief look atNative American education, traditional legends, the lifestyleof the Wabanaki, the Confederacy, seasonal activities, and thechanges that occured when the Europeans came. An awareness of theWabanakis in Boston and the role of the Boston Indian Council, Inc., areemphasized. -

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 The following document offers the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) recommended territorial acknowledgement for institutions where our members work, organized by province. While most of these campuses are included, the list will gradually become more complete as we learn more about specific traditional territories. When requested, we have also included acknowledgements for other post-secondary institutions as well. We wish to emphasize that this is a guide, not a script. We are recommending the acknowledgements that have been developed by local university-based Indigenous councils or advisory groups, where possible. In other places, where there are multiple territorial acknowledgements that exist for one area or the acknowledgements are contested, the multiple acknowledgements are provided. This is an evolving, working guide. © 2016 Canadian Association of University Teachers 2705 Queensview Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K2B 8K2 \\ 613-820-2270 \\ www.caut.ca Cover photo: “Infinity” © Christi Belcourt CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 Contents 1| How to use this guide Our process 2| Acknowledgement statements Newfoundland and Labrador Prince Edward Island Nova Scotia New Brunswick Québec Ontario Manitoba Saskatchewan Alberta British Columbia Canadian Association of University Teachers 3 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 1| How to use this guide The goal of this guide is to encourage all academic staff context or the audience in attendance. Also, given that association representatives and members to acknowledge there is no single standard orthography for traditional the First Peoples on whose traditional territories we live Indigenous names, this can be an opportunity to ensure and work. -

Vital Allies: the Colonial Militia's Use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2011 Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676 Shawn Eric Pirelli University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Pirelli, Shawn Eric, "Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676" (2011). Master's Theses and Capstones. 146. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VITAL ALLIES: THE COLONIAL MILITIA'S USE OF iNDIANS IN KING PHILIP'S WAR, 1675-1676 By Shawn Eric Pirelli BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In History May, 2011 UMI Number: 1498967 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1498967 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC.